The conviction that the United States was founded on Christianity collapses under scrutiny of the historical record. Pluralism and dissent quickly fractured the colonies from any vision of uniform faith.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Few myths in American history have proven as enduring as the notion that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. Advocates of this view often point to the religious convictions of certain colonists or the frequent invocations of Providence in Revolutionary rhetoric. Yet the historical and documentary record tells a more complex and, ultimately, contradictory story. The framers of the American republic, drawing heavily upon Enlightenment ideals, established a government whose legitimacy rested not on divine sanction but on the consent of the governed, and whose design explicitly rejected ecclesiastical authority in civic affairs. Far from erecting a Christian commonwealth, they enshrined principles of religious liberty, disestablishment, and pluralism that would have been anathema to theocratic rule.

One of the most striking affirmations of this intent appears in the Treaty of Tripoli, ratified unanimously by the Senate in 1797 and signed into law by President John Adams. Its eleventh article declared without ambiguity that “the government of the United States is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”1 This was no accidental phrasing. It reflected a shared understanding among the political leadership of the early republic that the new nation’s authority could not be grounded in sectarian identity. Instead, it arose from Enlightenment philosophy, classical republicanism, and the lived necessity of governing a religiously diverse people.

The absence of Christianity in the nation’s founding charter further underscores this point. The Constitution mentions neither God nor Jesus Christ. Article VI prohibits religious tests for officeholders, and the First Amendment forbids any law “respecting an establishment of religion.” These omissions were deliberate. James Madison, often hailed as the “Father of the Constitution,” had already insisted in his Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments that religion must remain wholly “left to the conviction and conscience of every man.”2 Thomas Jefferson, likewise, envisioned a “wall of separation between church and state.”3 The establishment of a secular republic was not an oversight but a conscious act of construction.

What follows will demonstrate, through an examination of primary documents and secondary scholarship, that the United States was not founded upon Christianity. It will situate the founding within the religious pluralism of the colonial period, trace the influence of Enlightenment thought upon the framers, and examine the constitutional and diplomatic evidence of secular design. The personal convictions of key founders, often deistic or skeptical of organized religion, will be considered alongside later judicial interpretations that reaffirmed the secular nature of the republic. Finally, the essay will address the persistence of the “Christian nation” myth, showing how nineteenth- and twentieth-century movements reshaped the memory of the founding for ideological ends. Only by disentangling historical fact from later invention can we recover the true origins of the American experiment in self-government.

Colonial Background: Christianity and Pluralism Before 1776

The colonies that would eventually form the United States were never uniform in their religious character. New England, particularly Massachusetts, bore the imprint of Puritan settlement, its early leaders envisioning a “city upon a hill” that might serve as a beacon of godly order.4 In Virginia, the Anglican Church enjoyed legal establishment, supported by taxation and wielding considerable influence in civil life.5 Pennsylvania, by contrast, became a haven for Quakers under the leadership of William Penn, while Maryland was initially founded as a refuge for English Catholics. The spectrum of belief and practice extended beyond the Christian confessions: enslaved Africans brought diverse spiritual traditions, and Indigenous peoples continued to maintain their own cosmologies despite missionary pressures.

Religious intolerance was a defining feature of many colonial societies. In Puritan Massachusetts, dissenters such as Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson were banished for challenging orthodoxy.6 The persecution of Baptists, Quakers, and other dissenters underscored the fragility of conscience under systems that yoked church and state together. Williams, in particular, would come to articulate a radical vision of religious liberty in his Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (1644), arguing that “forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils” and that genuine faith required freedom.7 Though his colony in Rhode Island remained exceptional, his principles foreshadowed later constitutional arrangements.

The eighteenth century brought gradual change, particularly through the intellectual and spiritual ferment of the Great Awakening. The revivalist preachers of this era fractured denominational monopolies, underscoring the possibility of religious pluralism by appealing directly to individual conscience.8 By the time of the Revolution, no single denomination commanded universal authority. Instead, Americans lived in a patchwork of sects and traditions, with growing acceptance, albeit uneven, of diversity. This pluralism posed a practical dilemma for the founders: how could a new nation bind together peoples of different creeds without privileging one faith over another?

The answer lay in experiments with legal disestablishment at the state level. Virginia became a crucial testing ground. After years of debate, the passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786, drafted by Thomas Jefferson and championed by James Madison, declared that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever.”9 This law not only ended the Anglican establishment in Virginia but also signaled a broader ideological shift. It revealed a growing conviction that liberty of conscience was not merely a toleration extended by rulers, but a natural right belonging to all.

Thus, on the eve of independence, the colonies presented a paradox. Many had been founded with explicit religious purposes, and coercion in matters of belief remained widespread. Yet the increasing diversity of denominations, coupled with the ferment of dissent and revival, made religious monopoly unsustainable. Out of this crucible of conflict and plurality would emerge the conviction that a just republic could not be founded upon Christianity alone, but had to rest on principles that transcended any single creed.

Enlightenment Influences on the Founders

The intellectual world of the eighteenth century was saturated with Enlightenment ideals. American leaders were deeply engaged with the works of European philosophers who placed reason, natural law, and human rights at the center of political life. John Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) circulated widely in the colonies and provided perhaps the most direct framework for arguments about liberty of conscience. Locke argued that civil government had “no power to enforce by law…any articles of faith or forms of worship,”10 and that coercion in religion produced only hypocrisy. His writings supplied a vocabulary for thinking about rights as inalienable and not subject to clerical control.

Montesquieu and Voltaire also left profound marks on the American imagination. Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws (1748) emphasized the dangers of concentrated authority and the necessity of checks and balances.11 Voltaire, with his relentless critique of clerical power and advocacy for tolerance, provided both inspiration and rhetorical ammunition. Even where the founders did not wholly embrace their more radical positions, they absorbed a sensibility that political legitimacy rested on reasoned consent rather than divine mandate.

Thomas Jefferson embodied this Enlightenment spirit in his political and intellectual life. In Notes on the State of Virginia, he denounced state support for religion, warning that “the legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others.”12 His authorship of the Declaration of Independence, with its appeal to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God,” reflected this rationalist orientation: the phrase signaled not an invocation of Christian theology but a reference to Enlightenment natural law theory.

James Madison carried these insights further in his Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785), a withering critique of efforts to tax Virginians in support of Christian teachers. “Who does not see,” he asked, “that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects?”13 His reasoning distilled Enlightenment skepticism into practical governance, demonstrating the dangers of state involvement in religious life.

Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton likewise reflected Enlightenment rationalism, albeit in different registers. Franklin’s writings reveal a pragmatic deism that emphasized virtue, civic responsibility, and inquiry over orthodoxy.14 Hamilton, though less consistently skeptical, employed Enlightenment arguments in the Federalist Papers to explain the necessity of a republic designed by reason rather than revelation.

Together, these intellectual influences prepared the ground for a constitution that would deliberately omit any reference to divine authority. The framers were not hostile to religion in private life, but they were determined to construct a political order in which no creed could claim official supremacy. The Enlightenment did not simply influence the founders; it provided the very scaffolding upon which they built a secular republic.

The Constitution and the Absence of God

When the delegates gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, they undertook the monumental task of drafting a new frame of government. What emerged from their deliberations was a charter remarkable not only for its structure of checks and balances but also for its conspicuous omission: God is nowhere mentioned. Neither Jesus Christ nor Christianity appears in the text. This silence was not an oversight but an intentional break with centuries of political tradition in which legitimacy was claimed through divine sanction.

Article VI stands as a landmark of this secular architecture. Its sweeping declaration that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States” dismantled one of the most entrenched practices of the Old World.15 In England, the Test Acts had long barred Catholics and dissenters from office, binding civic identity to Anglican orthodoxy. By contrast, the American Constitution rejected the idea that public service could be contingent on creed. This was revolutionary not only in the eighteenth-century context but in the broader history of Western governance.

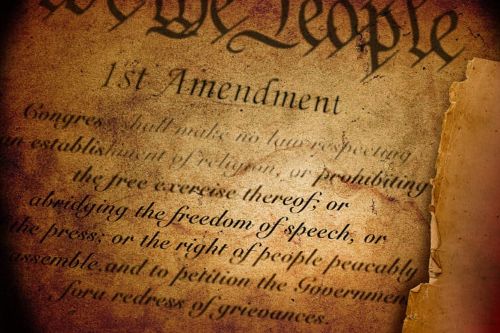

The First Amendment, adopted in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights, reinforced this principle. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”16 These twin clauses, the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, ensured both that the federal government would not privilege a religion and that individuals retained liberty of conscience. Although the amendment did not at first apply to state governments, its language crystallized a national commitment to religious neutrality.

Debates at the Constitutional Convention reveal that religion was rarely a focal point, a fact that itself underscores the founders’ priorities. James Madison, Gouverneur Morris, and Alexander Hamilton were more concerned with questions of representation, executive authority, and federalism than with theological matters. Even when Benjamin Franklin moved for prayer at the convention, the motion quietly failed, suggesting that the delegates preferred pragmatic deliberation over public piety.17

The omission of divine reference also extended to the preamble. Instead of appealing to God, as many state constitutions did, the federal charter invoked “We the People.” This rhetorical shift grounded legitimacy in popular sovereignty rather than in heavenly authority. It marked a decisive break from monarchies and theocracies alike, establishing a government accountable to citizens, not to clerics.

Critics at the time recognized the significance of this absence. Some clergy condemned the Constitution as “godless,” warning that a nation without explicit religious foundations would crumble.18 Yet the framers stood firm. Their design reflected both Enlightenment conviction and the practical necessity of governing a religiously diverse people. The Constitution’s silence on God was not a gap to be filled but a boundary to be respected.

The Treaty of Tripoli and Early Diplomatic Secularism

If the Constitution’s silence on religion left any ambiguity, the Treaty of Tripoli clarified matters in unmistakable terms. Negotiated with the Muslim state of Tripoli and ratified unanimously by the United States Senate in 1797, the treaty sought to ensure peace and protect American commerce in the Mediterranean. Its eleventh article, however, transcended its immediate diplomatic purpose and spoke directly to the religious identity of the republic: “As the government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion…it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility of Mussulmen.”19

This declaration was not a casual aside but a deliberate assurance to the Islamic world that the United States posed no religious threat. Its phrasing, far from being controversial, was accepted without objection. The Senate ratified the treaty unanimously, and President John Adams signed it into law, attesting in his proclamation that it was “advised and consented to by the Senate of the United States.”20 That the nation’s highest political authorities endorsed such a statement so early in the republic’s life testifies to the broad consensus that the government was secular in character.

Critics have sometimes suggested that the article reflected only the exigencies of diplomacy rather than an expression of principle. Yet this objection misses the deeper point: if the founders had conceived the United States as a Christian nation, they could not have so readily denied it in an official treaty. That they did so, unanimously and publicly, suggests that they saw no contradiction between the country’s true foundations and the assertion of religious neutrality abroad.

The treaty also highlights the practical realities of religious pluralism in an age of fragile alliances. The young republic had to reassure foreign powers that its politics were not beholden to sectarian hostility. In this respect, the secular identity of the United States was not merely a philosophical commitment but a diplomatic necessity. A Christian state would have found it difficult to maintain peace with Muslim powers without invoking the very crusading language that had poisoned European relations with the Islamic world for centuries.

Thus, the Treaty of Tripoli stands as one of the most definitive early statements of American secularism. It is a direct, unambiguous repudiation of the claim that the government was founded upon Christianity. By embedding that assertion in the language of international law, the founders affirmed for both domestic and foreign audiences that the new republic’s legitimacy rested on human consent and reasoned order, not divine ordination.

Founders’ Personal Beliefs: Deism and Religious Skepticism

Although the rhetoric of Providence peppered Revolutionary speeches and documents, the personal convictions of many leading founders reveal a striking distance from orthodox Christianity. Far from envisioning a government rooted in biblical authority, these figures approached religion with varying degrees of skepticism, rationalism, or pragmatic detachment.

Thomas Jefferson epitomized this orientation. In private correspondence, he referred to the doctrine of the Trinity as “incomprehensible jargon.”21 His Notes on the State of Virginia underscored his conviction that civil authority extended only to actions that injured others, not to matters of belief.22 Jefferson’s Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, the so-called “Jefferson Bible,” systematically excised miracles and supernatural claims, leaving only Jesus’ ethical teachings.23 For Jefferson, religion was valuable only insofar as it promoted virtue, not dogma.

James Madison shared this skepticism of state involvement in religion, even while maintaining a private reverence for conscience. In his Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, he insisted that “religion is wholly exempt from the cognizance of Civil Society.”24 He consistently opposed attempts to privilege Christianity in public life, regarding them as encroachments upon individual liberty. Madison’s later correspondence also shows unease with public expressions of religion by government officials, which he feared blurred the line between church and state.

Benjamin Franklin embodied pragmatic deism. In his Autobiography, Franklin recalled that he came to doubt many aspects of Christian doctrine, embracing instead a belief in a Creator who governed through natural law rather than revelation.25 Though respectful of religion’s social utility, Franklin was clear that morality could exist independently of dogma. His epitaph, written in the style of a printer’s metaphor, makes no appeal to resurrection or Christian salvation.

George Washington proved more reticent, but his caution speaks volumes. Though he attended Anglican services and employed religious language in public addresses, he rarely mentioned Jesus Christ by name and often avoided taking communion.26 Clergy of his own day remarked on his habitual silence about Christian doctrine. His Farewell Address (1796) praised religion as a support for morality, yet in general terms that emphasized utility rather than divine truth.27

Even John Adams, sometimes invoked by Christian nationalists, revealed a highly unorthodox theology. In correspondence with Jefferson, he dismissed Calvinist doctrines of predestination and atonement as absurdities.28 His willingness to sign the Treaty of Tripoli, explicitly denying the Christian foundations of the nation, further reflects this divergence from orthodoxy.

Taken together, the personal beliefs of the founders demonstrate a pattern. While they varied in degree of skepticism, they shared a broad commitment to religious liberty, to natural law over revelation, and to secular governance. Christianity may have shaped their cultural vocabulary, but it did not dictate their political philosophy. The United States, in their design, was to be a republic where religion could flourish freely in private life, but without the sanction or supremacy of the state.

The Courts and the Secular Settlement

The work of the founders in separating church from state did not end with the ratification of the Constitution. Over the next two centuries, the Supreme Court and other federal courts would be repeatedly called upon to clarify the boundaries of religion and government. These cases reveal a consistent affirmation of the principle that the United States is not a Christian nation, but a secular republic where freedom of conscience is paramount.

The first significant case was Reynolds v. United States (1879), which addressed the practice of polygamy among Mormons. Chief Justice Morrison Waite, writing for a unanimous Court, drew a crucial distinction between belief and action. Religious belief, he argued, was inviolable; but actions in violation of civil law could not claim immunity on religious grounds.29 Importantly, Waite cited Jefferson’s 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptists, in which Jefferson spoke of a “wall of separation between church and state.”30 This invocation gave judicial sanction to the metaphor that would become the cornerstone of American church-state jurisprudence.

The principle was further developed in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), a case concerning the reimbursement of transportation costs for children attending parochial schools. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, famously declared: “Neither a state nor the federal government can…pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another.”31 Though the Court permitted the reimbursement on grounds of neutrality, its broader ruling affirmed that the Establishment Clause forbade any state-sponsored support for religion. Black explicitly traced this doctrine back to Madison and Jefferson, underscoring the Enlightenment legacy embedded in the Constitution.

Perhaps the most definitive rejection of Christian establishment came in Engel v. Vitale (1962), which struck down the recitation of state-composed prayers in public schools. The Court held that even voluntary prayer, when sponsored by government, violated the Establishment Clause. Justice Hugo Black again invoked history, noting that the framers had intended to prevent exactly this sort of entanglement between religion and state authority.32 The ruling provoked a storm of controversy, with critics denouncing the Court for “removing God from the schools.” Yet the decision reflected a faithful application of the founders’ principles: religion was to remain free, not established.

Later cases, including Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) and Lee v. Weisman (1992), continued to refine the contours of establishment and free exercise. The so-called Lemon Test, requiring that government actions have a secular purpose, neither advance nor inhibit religion, and avoid excessive entanglement, emerged as a doctrinal tool to guard the wall of separation.33 Though subsequent courts have narrowed its scope, the underlying commitment to neutrality persists as a defining feature of American constitutional law.

These decisions collectively reinforce what the founders themselves articulated in treaty, statute, and constitution: the United States is not founded on Christianity. It is a secular republic whose government may neither impose belief nor elevate one creed above another. The judiciary, in repeatedly invoking the wisdom of Jefferson and Madison, has ensured that this principle endures as more than theory. It remains a living safeguard of liberty in a nation that has always been religiously diverse.

The Myth of a Christian Nation: 19th–21st Century

Despite the Constitution’s silence on Christianity and the founders’ clear rejection of religious establishment, the idea of the United States as a Christian nation began to gain traction in the nineteenth century. This development reflected less the reality of the founding than the anxieties of a rapidly changing society.

The myth took root most visibly during the Civil War era, when the National Reform Association, formed in 1863, campaigned to amend the Constitution to acknowledge “the Lord Jesus Christ as the ruler among the nations.”34 Though the effort failed, it reflected a growing impulse to claim Christian identity as a bulwark against social upheaval. This impulse intensified as immigration diversified the nation’s religious landscape with Catholics, Jews, and later non-Christian communities. The rhetoric of “Christian America” became a way to assert cultural dominance in the face of pluralism.

The Cold War marked a decisive turning point. In the ideological struggle against atheistic communism, politicians and religious leaders alike promoted a civil religion rooted in vaguely Christian imagery. In 1954, Congress added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance.35 Two years later, “In God We Trust” became the official national motto.36 Both measures were not expressions of founding principle but responses to contemporary fears, designed to contrast the United States with the Soviet Union. By embedding religious language into civic ritual, they reinforced the illusion of a Christian foundation.

The myth persisted into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, gaining new political momentum with the rise of the Religious Right. Leaders such as Jerry Falwell and organizations like the Moral Majority popularized the idea that the founders intended America to be a Christian republic.37 This narrative became a powerful mobilizing tool in debates over abortion, school prayer, and LGBTQ rights. Yet historical evidence consistently undermines the claim. Scholars such as Steven K. Green, Kevin Kruse, and Andrew Seidel have demonstrated that the Christian nation narrative is a modern invention, more a product of cultural politics than historical fact.38

The persistence of this myth reveals a paradox. The very freedoms secured by the founders (freedom of speech, freedom of religion) have allowed Christian nationalism to flourish rhetorically, even as the legal framework of the republic remains secular. This tension continues to shape American public life. On the one hand, courts and historians affirm the founders’ intent to separate church and state. On the other, popular rhetoric and political movements often insist that the United States was, and must remain, a Christian nation.

In this sense, the myth of a Christian America is itself a testament to the durability of pluralism. It persists not because it reflects historical truth, but because it functions as a contested symbol in the ongoing struggle to define national identity. The historical record remains clear: the founders established a secular republic. The persistence of the Christian nation narrative demonstrates the power of myth to shape memory, even when it runs counter to fact.

Conclusion

The conviction that the United States was founded on Christianity collapses under scrutiny of the historical record. The colonies may have begun with religious purposes, but pluralism and dissent quickly fractured any vision of uniform faith. Enlightenment philosophy, more than biblical doctrine, guided the framers in designing a republic where sovereignty derived from the people rather than divine right. The Constitution’s silence on God, the prohibition of religious tests, and the First Amendment’s guarantees of disestablishment and free exercise established the framework of a secular government.

The Treaty of Tripoli, with its explicit denial that the nation was “in any sense founded on the Christian religion,” made this principle unmistakable both to domestic audiences and to foreign powers. The private beliefs of the founders, from Jefferson’s rationalist deism to Madison’s insistence on liberty of conscience, further underscore their commitment to secular governance. Later judicial rulings, from Reynolds to Engel, reaffirmed this separation, insisting that the state may neither privilege nor suppress religion.

And yet, as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries unfolded, the myth of a Christian America grew in cultural power. Born of social anxiety and political opportunism, it reshaped public memory even as it departed from historical truth. The Cold War’s embrace of civil religion, the rise of the Religious Right, and the contemporary rhetoric of Christian nationalism continue to obscure the reality of the founding.

Recovering that reality is not merely a matter of historical accuracy. It is essential to the preservation of the liberty the founders sought to secure. A republic founded on Christianity would inevitably privilege some citizens over others, undermining the equality promised in the Declaration and the rights protected by the Constitution. A republic founded on religious freedom, by contrast, allows diverse beliefs to flourish without coercion or favoritism. That was the founders’ achievement: a nation whose government belonged to all, regardless of creed.

The claim that America was founded on Christianity is a myth, powerful but false. The truth, grounded in documents, debates, and decisions, is that the United States was founded on principles of liberty, reason, and consent. To acknowledge this is not to deny the influence of religion on American culture, but to recognize that the genius of the founding lay precisely in its refusal to elevate any faith above others. In the words of Jefferson, “truth is great and will prevail if left to herself.”39 The enduring task of American democracy is to ensure that she continues to do so.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary, art. 11, 1797, in American State Papers: Foreign Relations, vol. 2, 18.

- James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, 1785, in The Papers of James Madison, vol. 8, ed. Robert A. Rutland (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 298.

- Thomas Jefferson to the Danbury Baptist Association, January 1, 1802, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 16, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), 281.

- John Winthrop, “A Modell of Christian Charity,” 1630, in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd series, vol. 7 (Boston, 1838), 31–48.

- Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 48–55.

- Michael P. Winship, Godly Republicanism: Puritans, Pilgrims, and a City on a Hill (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 143–46.

- Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (London, 1644), 3.

- Harry S. Stout, The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 112–19.

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, 1786, in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., The Portable Thomas Jefferson (New York: Penguin, 1977), 252.

- John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), in James H. Tully, ed., A Letter Concerning Toleration (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983), 27.

- Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, trans. Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 157–64.

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), in Peterson, Portable Jefferson, 216.

- Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance, 299.

- Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Louis P. Masur (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003), 111–15.

- U.S. Constitution, art. VI, sec. 3.

- U.S. Constitution, amend. I.

- Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), 452.

- Isaac Kramnick and R. Laurence Moore, The Godless Constitution: A Moral Defense of the Secular State (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 39.

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary, art. 11, in American State Papers: Foreign Relations, vol. 2, 18.

- John Adams, Proclamation of the Treaty of Tripoli, June 10, 1797, in The Works of John Adams, vol. 9, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, 1854), 94.

- Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, April 11, 1823, in The Adams-Jefferson Letters, ed. Lester J. Cappon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 594.

- Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 216.

- Thomas Jefferson, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989).

- Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance, 299.

- Franklin, Autobiography, 111–15.

- Paul F. Boller Jr., George Washington and Religion (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1963), 92–98.

- George Washington, Farewell Address, September 19, 1796, in A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, vol. 1, ed. James D. Richardson (Washington, D.C., 1896), 213–25.

- John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, September 14, 1813, in The Adams-Jefferson Letters, 369–70.

- Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145, 166 (1879).

- Jefferson to the Danbury Baptists, in Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 16, 281.

- Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1, 15–16 (1947).

- Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 424–25 (1962).

- Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 612–13 (1971).

- Robert T. Handy, A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 107–10.

- Congressional Record, 83rd Congress, 2nd sess., 1954, 100.

- Public Law 84–851, approved July 30, 1956.

- Daniel K. Williams, God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 56–60.

- Steven K. Green, Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (New York: Basic Books, 2015); Andrew L. Seidel, The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism Is Un-American (New York: Sterling, 2019).

- Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, June 5, 1819, in The Adams-Jefferson Letters, 505.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Adams, John. The Works of John Adams. Edited by Charles Francis Adams. Vol. 9. Boston: Little, Brown, 1854.

- Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by Louis P. Masur. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003.

- Jefferson, Thomas. The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Boston: Beacon Press, 1989.

- ———. Notes on the State of Virginia. In The Portable Thomas Jefferson, edited by Merrill D. Peterson, 187–252. New York: Penguin, 1977.

- ———. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Vol. 16. Edited by Andrew A. Lipscomb. Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904.

- Locke, John. A Letter Concerning Toleration. Edited by James H. Tully. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983.

- Madison, James. The Papers of James Madison. Vol. 8. Edited by Robert A. Rutland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

- Montesquieu. The Spirit of the Laws. Translated by Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary. 1797. In American State Papers: Foreign Relations, vol. 2. Washington, D.C.

- U.S. Constitution. 1787.

- U.S. Supreme Court. Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

- ———. Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

- ———. Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971).

- ———. Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879).

- Washington, George. Farewell Address. September 19, 1796. In A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, vol. 1. Edited by James D. Richardson. Washington, D.C., 1896.

- Williams, Roger. The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution. London, 1644.

- Winthrop, John. “A Modell of Christian Charity.” 1630. In Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd series, vol. 7. Boston, 1838.

Secondary Sources

- Boller, Paul F. Jr. George Washington and Religion. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1963.

- Green, Steven K. Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Handy, Robert T. A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

- Kramnick, Isaac, and R. Laurence Moore. The Godless Constitution: A Moral Defense of the Secular State. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005.

- Kruse, Kevin M. One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

- Seidel, Andrew L. The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism Is Un-American. New York: Sterling, 2019.

- Stout, Harry S. The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Winship, Michael P. Godly Republicanism: Puritans, Pilgrims, and a City on a Hill. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.