From the plague riots of late medieval Europe to the COVID-19 demonstrations of the twenty-first century, the history of uprisings over health care reveals a consistent theme.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Health care has never been a purely clinical matter. From the first plague ordinances of the late Middle Ages to the modern controversies of COVID-19, medicine has carried profound political weight. It determines who receives attention in times of crisis, whose bodies are deemed expendable, and how states define the limits of authority over life and death. The healing professions, civic officials, and rulers alike have claimed jurisdiction over the sick, and yet their efforts have just as often provoked distrust and revolt as gratitude. When health measures intersect with fear, inequality, or coercive authority, they ignite a combustible mix that can lead not simply to discontent, but to open protest, riots, and even organized movements of resistance.

This study traces a longue durée of uprisings tied to health and medicine, beginning with medieval plague riots, moving through early modern anatomy controversies and nineteenth-century cholera panics, and culminating in the politicized medical struggles of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What emerges across these episodes is a pattern: communities rise in opposition not merely when confronted with disease, but when medical authority becomes entangled with contested sovereignty, class tensions, or the perception of betrayal. In 1788, New Yorkers stormed a hospital over rumors of body snatching; in 1831, Russians attacked physicians they believed were poisoning patients; in the 1980s, AIDS activists chained themselves to government buildings demanding drugs and recognition. Each case reveals medicine as a mirror of social trust, or its collapse.

The guiding thesis here is simple: health is never neutral. Oaths, quarantines, public health edicts, and medical experiments all raise the same underlying question: who has the right to command bodies in the name of health? The answers, whether in the form of mobs tearing down pest houses in plague-ridden London, cholera crowds in St. Petersburg, or protesters storming capitols during pandemic lockdowns, mark the shifting boundaries of state legitimacy. This essay argues that uprisings over health care illuminate more than public panic; they reveal the fault lines of political order itself, exposing moments when medicine ceases to heal and becomes instead a battlefield of power.

Medieval and Early Modern Origins

The Black Death and Medical Distrust

The mid-fourteenth century’s Black Death remains the archetype of epidemic catastrophe, killing perhaps one-third to one-half of Europe’s population between 1347 and 1353.¹ Yet beyond its mortality, it generated a legacy of distrust that set a template for later health-related unrest. Physicians, unable to halt the plague, became objects of suspicion. Civic leaders who imposed harsh quarantines were seen not as protectors but as agents of cruelty, tearing families apart by confining the sick in pest houses. In many towns, crowds resisted such measures by force, breaking quarantine or attacking officials tasked with enforcement.²

Even more violently, scapegoats were created: Jews were accused of poisoning wells and spreading disease, leading to massacres in Strasbourg, Mainz, and other cities.³ Here, medicine, rumor, and politics fused into an explosive mix. Health crises became opportunities for communities to redefine loyalty, belonging, and blame. As Samuel Cohn argues, the Black Death “transformed” European societies not simply demographically but culturally, by revealing the limits of medical and political authority.⁴

London Plague Riots

This distrust resurfaced in early modern England, where plague was a recurring terror into the seventeenth century. The state’s strategy increasingly relied on coercive quarantines and the forcible removal of the sick into “pest houses.” Yet these measures were deeply unpopular, and riots often erupted in resistance. In 1603, Londoners assaulted plague officials who tried to board up infected houses, and in later outbreaks mobs freed the quarantined by breaking down doors.⁵ Families preferred to risk contagion rather than lose relatives to what was effectively a prison.

Paul Slack has shown how these riots reflected both fear of disease and resentment of unequal enforcement: the poor were sealed into their homes, while the wealthy could often bribe their way free.⁶ In this sense, plague riots were not merely about medical policy but about class power and the credibility of the state. By violently rejecting health ordinances, London’s poor asserted a grim autonomy: they would die on their own terms rather than under the dictates of magistrates and physicians.

The persistence of such riots illustrates how public health was perceived less as a communal safeguard than as an instrument of authority. Medical policy became entangled with older cultural memories of tyranny, feeding suspicion that health orders masked political domination.⁷ In this way, the plague riots of London did more than challenge the city’s sanitary regime: they foreshadowed later conflicts in which disease management became inseparable from contestations over legitimacy and freedom.

Anatomy Riots and the “Doctors’ Riot” in New York (1788)

If plague riots reflected distrust of public health measures, the anatomy riots of the eighteenth century exposed anxieties about the boundaries of the body itself. In Britain and its colonies, medical schools faced chronic shortages of cadavers for teaching and dissection. Legal supply, primarily the bodies of executed criminals, was never sufficient, and thus physicians and students turned to “resurrection men” who robbed graves, disproportionately those of the poor. The practice generated widespread fear that physicians exploited the marginalized even in death.

These tensions erupted violently in New York City in April 1788. Rumors spread that students at New York Hospital had desecrated local graves and were mocking cadavers. When a group of boys reportedly saw a medical student waving a severed arm from a window, crowds gathered and stormed the building.⁸ The ensuing “Doctors’ Riot” grew into a days-long confrontation in which thousands of New Yorkers besieged hospitals, destroyed medical equipment, and threatened to lynch physicians. Militia were called in, and at least six people were killed before order was restored.⁹

The Doctors’ Riot revealed how fragile public trust in medicine remained in the early republic. For the city’s working classes, physicians appeared less as healers than as predators, extracting knowledge from the bodies of the powerless.¹⁰ As Michael Sappol has argued, anatomy symbolized “a traffic of dead bodies” that mapped social hierarchy onto medical practice.¹¹ The riot thus underscored how questions of health were inseparable from questions of justice: whose bodies could be claimed, and by what right?

Cholera and the Politics of Public Health

Russia’s Cholera Riots (1830–31)

In the nineteenth century, cholera swept repeatedly across Eurasia, producing not only fear but also violent upheavals. Russia, where the disease struck in 1830–31, saw some of the most dramatic cholera riots. Suspicion spread that physicians and officials were deliberately poisoning wells or killing patients in hospitals. In St. Petersburg, mobs stormed medical facilities, attacked doctors, and tore patients from infirmaries. Similar scenes occurred in Saratov, Astrakhan, and other provincial centers.¹² The violence was intense: thousands were arrested, many were executed, and the state responded with both repression and attempts at public reassurance.

The riots revealed the degree to which medicine was entangled with autocracy. In a system already marked by distrust between state and subjects, coercive quarantines and medical interventions were read as further instruments of control. John Davis notes that peasants often interpreted state action not as protective but as hostile, assuming cholera measures masked attempts at population reduction.¹³ Here, disease was not a neutral biological force but a prism through which existing political fears were refracted into deadly confrontation.

Western Europe: Britain and Italy

Similar suspicions erupted in Western Europe during the same period. In Britain, where cholera struck in the early 1830s, working-class communities resisted sanitary boards that imposed new forms of inspection and burial. Crowds accused doctors of dissecting cholera victims for profit and rioted in Liverpool, Sunderland, and London.¹⁴ In Italy, Naples experienced violent resistance to quarantine measures, with mobs freeing the confined and burning barricades.¹⁵

As Richard Evans has shown in his study of Hamburg, cholera magnified existing divisions over class and governance. The poor saw sanitary reform not as benevolent but as a means of disciplining their neighborhoods, while elites embraced it as evidence of scientific modernity.¹⁶ In both Eastern and Western Europe, then, cholera produced an identical crisis: when medical authority appeared coercive or unequal, it became indistinguishable from tyranny, sparking rebellion.

Modern Struggles over Health and Rights

Britain and the Creation of the NHS (1940s)

By the mid-twentieth century, the terrain of medical protest shifted from fear of contagion to disputes over access and control. In Britain, the Second World War created momentum for universal health care, culminating in the 1946 National Health Service Act. Yet the NHS’s creation was far from uncontested. Physicians’ groups, particularly the British Medical Association, resisted what they saw as state intrusion into professional autonomy. Some threatened strikes or mass resignations, arguing that compulsory service under a national system compromised the independence of medical practice.¹⁷

At the same time, labor organizations and working-class movements pushed forcefully for the establishment of a publicly funded system. Wartime sacrifice, rationing, and mass mobilization had produced expectations of postwar equity, and health care became a rallying point for social rights. The resulting debates, though less violent than plague or cholera riots, were nonetheless confrontational: public marches, fiery pamphlets, and tense parliamentary battles shaped the final structure of the NHS.¹⁸ Charles Webster notes that the NHS emerged not simply as a health reform but as a political settlement, negotiated between medical elites, trade unions, and the postwar Labour government.¹⁹

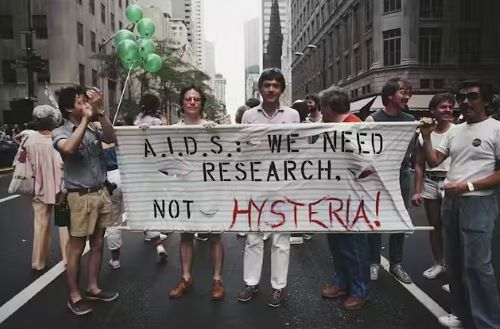

AIDS Activism in the United States (1980s–90s)

If Britain’s NHS debates revolved around inclusion and professional autonomy, the American AIDS crisis revealed the deadly consequences of exclusion. When the epidemic erupted in the early 1980s, government inaction and pharmaceutical inertia left patients without effective treatment. Gay communities, already marginalized, saw neglect as a political choice rather than a medical failure. In response, activists formed groups such as ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which staged militant demonstrations at the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and on Wall Street.²⁰

These actions were intentionally confrontational. “Die-ins” dramatized the mass deaths occurring while drugs languished in trials, and protesters chained themselves to government buildings to demand accelerated approval processes.²¹ As Sarah Schulman documents, ACT UP reshaped the politics of health care by reframing patients as experts and by forcing institutions to respond to grassroots pressure.²² Steven Epstein argues that AIDS activism transformed biomedical research itself, creating new models of patient involvement in drug testing.²³ What had begun as desperation became one of the most effective health rights movements in modern history, turning bodies into instruments of protest in a way that echoed, but also radicalized, earlier health uprisings.

Contemporary Health Protests

U.S. Health Care Reform Debates (2009–2010)

The most contentious health care battles in recent U.S. history unfolded around the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In 2009 and 2010, as Congress debated the bill, town halls and public meetings became flashpoints. Protesters disrupted events, shouting down lawmakers and in some cases turning violent.²⁴ For opponents, the ACA symbolized government overreach and an existential threat to personal liberty; for supporters, it was a long-delayed recognition of health care as a right. The heated atmosphere bore resemblance to earlier health uprisings, though refracted through partisan politics rather than epidemics.

The intensity of these confrontations demonstrated how health reform could serve as a proxy for broader anxieties about state power, taxation, and social change.²⁵ While the ACA ultimately passed in March 2010, the protests signaled a deep fracture in American political culture, one that continues to shape debates over coverage, mandates, and the role of government in medical care.

COVID-19 Protests Worldwide (2020–2022)

The COVID-19 pandemic reignited this tradition of health-related protest on a global scale. Lockdowns, mask mandates, and vaccine requirements sparked mass demonstrations from the United States to Europe. In the Netherlands, protesters clashed with police during riots against curfews.²⁶ In France, the introduction of health passes triggered widespread marches.²⁷ In the United States, demonstrations erupted at state capitols, with armed groups sometimes appearing to defy restrictions.

Michael Bang Petersen has argued that these protests reflected not simply skepticism of science but broader mistrust of elites and institutions.²⁸ Public health measures became lightning rods for grievances about inequality, political legitimacy, and personal freedom. Just as plague quarantines in seventeenth-century London provoked riots, so too did pandemic restrictions in the twenty-first century expose the limits of compliance when authority is not trusted. Simon Schama has noted that pandemic protests dramatize an enduring paradox: medicine seeks to preserve life, yet its imposition of collective discipline often generates rebellion.²⁹

Conclusion

From the plague riots of late medieval Europe to the COVID-19 demonstrations of the twenty-first century, the history of uprisings over health care reveals a consistent theme: medicine is never neutral. Each moment of unrest (whether sparked by quarantines in London, grave-robbing in New York, cholera wards in St. Petersburg, or the bureaucratic pace of AIDS drug approval) underscores that health policy is inseparable from questions of power, legitimacy, and trust.

What links these episodes is not merely disease but perception: that the institutions charged with preserving life were, in fact, serving other masters. In fourteenth-century Strasbourg, Jews were massacred because people believed plague was being deliberately spread. In 1831 Russia, mobs attacked doctors for supposedly poisoning cholera patients. In 1980s America, ACT UP activists saw government indifference as a form of sanctioned death. In 2020, citizens across the world framed mask mandates or vaccine requirements as political coercion rather than public protection. Across time and place, the common thread is suspicion that medicine has ceased to be a safeguard and has instead become an arm of domination.

Yet these protests also demonstrate the capacity of communities to redefine health itself as a matter of rights. The creation of Britain’s NHS, though fraught with conflict, emerged as a settlement between state, profession, and citizenry. AIDS activism transformed biomedical research by demanding patient inclusion. Even the most violent riots reflected not only fear but assertions of autonomy, claims that ordinary people must retain a say in the governance of their own bodies.

As Simon Schama has observed, pandemics “dramatize the paradox of medicine: in seeking to preserve life, it imposes discipline.”³⁰ This paradox has produced centuries of rebellion, each episode revealing that health is always political. To trace the history of health uprisings is thus to trace the contested boundary between rulers and ruled, between expert authority and popular resistance. The enduring question remains as urgent today as in 1348: who commands loyalty when life itself is at stake, the healer, the state, or the people?

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ole J. Benedictow, The Black Death, 1346–1353: The Complete History (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2004), 380–82.

- Samuel K. Cohn, The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe (London: Arnold, 2002), 105–10.

- Cohn, The Black Death Transformed, 122–28.

- Ibid., 1–3.

- Paul Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (London: Routledge, 1985), 203–7.

- Slack, Impact of Plague, 210–13.

- Alexandra Walsham, “Plague and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern England,” in Epidemics and Ideas: Essays on the Historical Perception of Pestilence, ed. Terence Ranger and Paul Slack (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 123–25.

- Matthew Turner, “The Doctors’ Riot of 1788,” Hektoen International (Fall 2023).

- Brown, “Doctors’ Riot,” 15–18.

- Samuel L. Mitchill, “Letter on the Late Tumult,” New-York Journal, April 1788, cited in Brown, “Doctors’ Riot,” 21.

- Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 3–7.

- Bosin, Yury V., “Russia, Cholera Riots of 1830-1831,” International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (London: Blackwell Publishing, 2009).

- Davis, “Cholera Riots,” 136–40.

- Michael Durey, The Return of the Plague: British Society and the Cholera, 1831–2 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1979), 85–92.

- Frank M. Snowden, Naples in the Time of Cholera, 1884–1911 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 27–31.

- Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 45–52.

- Charles Webster, The National Health Service: A Political History, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 23–29.

- Nicholas Timmins, The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State (London: HarperCollins, 1995), 135–41.

- Webster, NHS: A Political History, 45–49.

- Douglas Crimp, ed., AIDS Demo Graphics (Seattle: Bay Press, 1990), 12–15.

- Gregg Bordowitz, Documenta X: AIDS Timeline (Kassel: Cantz Verlag, 1997), 33–37.

- Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 89–95.

- Steven Epstein, Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 329–34.

- Lawrence R. Jacobs and Theda Skocpol, Health Care Reform and American Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 54–59.

- Jacobs and Skocpol, Health Care Reform, 60–65.

- BBC News, “Covid: Dutch Police Break Up Anti-Lockdown Protest,” March 14, 2021.

- Reuters, “Tens of Thousands Protest Across France Against COVID Health Pass,” July 17, 2021.

- Petersen, Michael Bang, “A Practical Agenda for Incorporating Trust into Pandemic Preparedness and Response,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2024): 440-447.

- Schama, Simon. Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations. New York: Ecco (2023).

- Schama, “The Politics of Pandemics,” 6.

Bibliography

- BBC News. “Covid: Dutch Police Break Up Anti-Lockdown Protest.” March 14, 2021.

- Benedictow, Ole J. The Black Death, 1346–1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2004.

- Bordowitz, Gregg. Documenta X: AIDS Timeline. Kassel: Cantz Verlag, 1997.

- Bosin, Yury V. “Russia, Cholera Riots of 1830-1831.” International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (London: Blackwell Publishing, 2009), 2877-2878.

- Cohn, Samuel K. The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. London: Arnold, 2002.

- Crimp, Douglas, ed. AIDS Demo Graphics. Seattle: Bay Press, 1990.

- Durey, Michael. The Return of the Plague: British Society and the Cholera, 1831–2. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1979.

- Epstein, Steven. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Evans, Richard J. Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Jacobs, Lawrence R., and Theda Skocpol. Health Care Reform and American Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Mitchill, Samuel L. “Letter on the Late Tumult.” New-York Journal, April 1788. Cited in Brown, “Doctors’ Riot.”

- Petersen, Michael Bang. “A Practical Agenda for Incorporating Trust into Pandemic Preparedness and Response.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2024): 440-447.

- Reuters. “Tens of Thousands Protest Across France Against COVID Health Pass.” July 30, 2021.

- Sappol, Michael. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Schama, Simon. Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations. New York: Ecco, 2023.

- Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.

- Slack, Paul. The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England. London: Routledge, 1985.

- Snowden, Frank M. Naples in the Time of Cholera, 1884–1911. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Timmins, Nicholas. The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State. London: HarperCollins, 1995.

- Turner, Matthew. “The Doctors’ Riot of 1788.” Hektoen International (Fall 2023).

- Walsham, Alexandra. “Plague and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern England.” In Epidemics and Ideas: Essays on the Historical Perception of Pestilence, edited by Terence Ranger and Paul Slack, 122–52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Webster, Charles. The National Health Service: A Political History. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.