What had once been largely a domestic, community-managed process became a commercial enterprise characterized by standardized services, professional undertakers, and escalating costs.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the long nineteenth century, America’s dead required more than prayers and remembrance: they required coffins, labor, land, ceremony, transport, and upkeep. Behind every interment lay a bundle of economic choices, technologies, social expectations, and institutional constraints. Economically and socially, the act of dying was not a simple transition but a consumption event, a service industry, and a site of social obligation. The central question of this essay is: what did it cost to die in 19th-century America, and what do those costs reveal about the relationship between death, consumption, and social hierarchy?

This question sits at the intersection of several historiographical strands. Scholars of death and mourning have charted changing rituals, emotional regimes, and material culture (mourning dress, memorial stationery, wakes), but comparatively few have foregrounded the monetary burden of funerary practices. Meanwhile, economic and social historians have tended to leave death as a “black box” — a fixed mortality schedule — without considering what the transition implied for households in terms of sudden expenditures. By focusing tightly on cost and pricing, this essay aims to help bridge that divide: not merely to show how Americans died, but how much it cost them to die, and how that cost mattered in everyday life.

Two further claims guide this study. First, the monetization of death care was a gradual process, rooted in the shift from home-based funerals to professional undertaking, accelerated by the Civil War (especially via embalming and long-distance transport), and consolidated in the late century by the rise of funeral trade associations and mortuary standards. Second, because the consumption of funeral goods and services was visible, socially meaningful, and often financed on credit, funeral costs functioned as a site of social stratification: households that could not afford “respectable” funerals faced social judgment, indebtedness, or recourse to pauper burial.

But documenting those claims is not straightforward. The evidence is fragmentary and dispersed: undertaker bills survive only intermittently; cemetery board ledgers and sexton reports are patchy; probate and estate inventories often list only “funeral expenses” as a lump sum without breakdown; advertisements and mortuary manuals provide formal “price lists” that may not reflect market or local practice. As a result, this essay triangulates across multiple source types: probate records, undertaker and funeral home invoices, cemetery lot books and bylaws, mortuary manuals and trade publications, and contemporary newspapers and advertisements. Wherever possible, I compare dozens of case studies to highlight mundane variation (urban vs. rural, Northeast vs. South, wealthy vs. working class).

This essay is organized in three major parts. The first part reconstructs the emergence of the funeral marketplace and the conditions under which death care became a professionalized service. The second and largest part dissects the components of funeral and burial cost — coffins, embalming, undertaker labor, grave digging, transportation, monuments, etc. — and offers a sampling of empirical case studies. The third part assesses the burden of those costs on households, showing how families coped (credit, mutual aid societies, pauper burial) and how cost, consumption, and ritual intersected with inequality. Finally, I step back to consider what the “cost of death” can tell us about consumer culture, household economics, and social expectations in 19th-century America.

I do not claim to produce a fully exhaustive national “price table” of funerals (the sources never allow that). But by weaving together micro-evidence, institutional contexts, and interpretive frames, I aim to recover a more vivid and socially grounded picture of how Americans paid for dying — and how those costs, in turn, shaped memory, social order, and familial obligation.

The Marketplace of Death: The Rise of Professional Undertakers

Overview

In order to understand how funeral and burial costs came to matter in nineteenth-century America, one must first trace the transformation of death care from a family or community task into a marketable, professional service. This section shows how undertaking evolved, how the Civil War and embalming catalyzed change, and how funeral trade practices and associations shaped cost structures.

From Home Funerals to Specialized Undertaking

Early practices and “Laying Out”

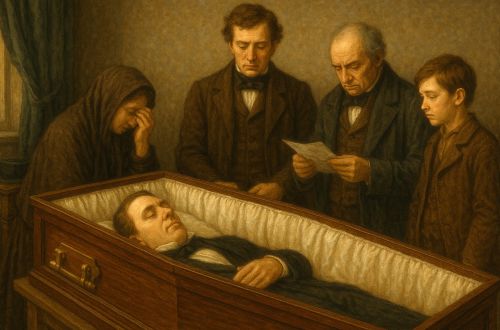

Before the mid-nineteenth century, most funerals in America were managed within the family or community network. Women of the household or community often washed, dressed, and laid out the corpse; a small group of neighbors might act as pallbearers; the body was kept at home, usually in a parlor or bedchamber, until burial.¹ Over time, local cabinetmakers or furniture makers (already skilled in woodworking and coffin construction) began to—as a practical extension—offer coffins or to assist in transporting the body to the grave.²

In many towns, the cabinetmaker was the de facto funeral supplier: he built coffins, sometimes lent hearses or wagons, and perhaps handled minor transport.³ The term “undertaker” gradually came to designate someone who “undertook” multiple tasks related to death care: coffin making, body handling, transport, funeral coordination.

The Gradual Professionalization of Undertaking

As urbanization, distance to cemeteries, and social expectations rose, the role of the undertaker expanded. In many cities by the mid to late nineteenth century, undertakers advertised not only coffins but complete funeral services, mourning accessories, hearses, and flower arrangements.⁴ In directories from cities such as Cleveland, it is not uncommon by the 1850s to find cabinet makers also listed as undertakers (for example, in 1857, 10 out of 16 cabinet makers in one directory also functioned as undertakers).⁵

Over the course of the late nineteenth century, undertaking became a full-time occupation. The U.S. Census first recorded “undertaker” as a discrete occupational category: in 1890, there were 9,891 persons listed as undertakers, rising to 16,189 in 1900.⁶ As the trade matured, undertakers increasingly separated from furniture trades, built dedicated funeral parlors, and emphasized specialized services (body preparation, embalming, viewing rooms, coordination).⁷

In parallel, undertakers sought to frame themselves as professionals rather than tradesmen, with claims about sanitary expertise, dignity, and technical knowledge of anatomy and preservation.

The Civil War, Embalming, and Transportation

The Civil War as a Turning Point

The American Civil War proved a pivotal moment for the funeral trade. The desire of families to reclaim fallen soldiers for burial at home pushed demand for body preservation and long-distance transport of remains.⁸ The logistical challenges of preserving bodies over rail journeys in summer heat necessitated improved techniques of preservation. In this context, embalming took on symbolic and practical significance.⁹

One prominent practitioner was Thomas Holmes, sometimes called the “father of American embalming.” During the war, he reportedly embalmed thousands of soldiers, charging as much as $100 per body, which elevated public awareness of arterial embalming techniques.¹⁰ After the war, Holmes and others marketed embalming to civilian funeral consumers.¹¹

Abraham Lincoln’s death and the elaborate funeral train that bore his body across multiple states also helped popularize embalming and national awareness of professional funerary display.¹²

Impact on Cost Structures and Funeral Timing

Because embalming extended the viable time window between death and burial, undertakers could schedule viewings, accommodate distant mourners, and provide more elaborate wakes. This lengthened interval increased the scale and complexity of funeral services and thus potential cost.¹³ Undertakers could more confidently charge for lying-in, visitation, and extended services, all of which contributed new cost components (rooms, chairs, decoration, lighting).

Moreover, the need to transport bodies (by rail, carriage, or wagon) introduced another layer of cost. Undertakers now had to factor the labor, vehicles, packaging, and logistics into their pricing.

Trade Associations, Mortuary Manuals, and Standardization

Mortuary Manuals, Trade Journals, and Published Price Lists

As undertaking matured, trade manuals and journals emerged, promoting standard practices, recommended pricing, and best methods. These texts attempted to professionalize and systematize what had previously been localized, ad hoc practices. They often presented model price lists or fee schedules, though actual local rates varied.

These publications had dual effects: they legitimized mortuary services (presenting them as technical, ethical, professional work) and also helped shape client expectations about what constituted a “normal” funeral. Undertakers could point to “industry standard” charges when justifying their prices.

Cemetery Superintendents and the Association of American Cemetery Superintendents

Another institutional actor shaping cost norms was the Association of American Cemetery Superintendents (AACS), founded in 1887. Its members set standards for plot layout, monument materials, vault and liner specifications, and cemetery maintenance.¹⁴ As cemetery boards adopted those standards (e.g. specifications for vaults, liners, or landscape design), their requirements affected how much undertakers or families needed to spend to satisfy cemetery regulations.

In effect, the interplay between undertakers and cemeteries ensured that price structures in one sector influenced those in the other.

Professional Positioning, Regulation, and Consumer Expectations

By the late nineteenth century, undertakers increasingly portrayed themselves as delicate custodians of dignity and health, distancing their business from ordinary handiwork. This rhetoric helped justify higher fees. In many places, states passed laws regulating embalming, coffin construction, or cemetery oversight, inserting a regulatory overlay on funeral commerce.¹⁵

At the same time, evolving consumer expectations (influenced by moral norms, middle-class aspiration, and advertisement) raised the benchmark for what a respectable funeral should include. As more families expected viewing rooms, polished coffins, mourning paraphernalia, and decorative elements, undertakers had leverage to inflate services above mere bare minimums.

Components of Funeral and Burial Costs

Overview

To appreciate the burden placed on nineteenth-century households, one must disaggregate the costs of a funeral into its parts. Families rarely faced a single lump sum; rather, they navigated a constellation of expenses: coffins, embalming, undertaker services, cemetery fees, monuments, and auxiliary outlays. Surviving records from undertaker ledgers, cemetery account books, and advertisements provide scattered but illuminating glimpses into these categories.

Coffins, Caskets, and Burial Containers

Plain Wood Coffins

The simplest and most affordable option for much of the century was a pine coffin, produced by a local carpenter or undertaker. Contemporary accounts suggest these could be procured for as little as two to three dollars in the 1840s, depending on locality.¹⁶ For the working poor, even this modest outlay could represent several days’ wages.

Metallic Burial Cases

At the opposite end of the spectrum were patented metallic burial cases, most famously the Fisk coffin. Introduced in the 1840s, these cast-iron cases promised airtight preservation and fashionable presentation through viewing windows. They commanded prices up to $100—an extraordinary figure in the mid-nineteenth century, often exceeding the monthly income of many laboring families.¹⁷ Their cultural cachet was reinforced by high-profile uses, such as the burial of congressmen and prominent businessmen.

Shifts toward Caskets

By the 1870s, the “casket”—rectangular, hinged, lined, and often mass-produced—had begun to replace the traditional coffin. Undertaker trade journals emphasized its elegance and comfort, but its price was correspondingly higher, with even modestly lined caskets costing $20–30, and luxury versions running well above $100.¹⁸ The proliferation of casket catalogues both standardized offerings and fostered consumer aspiration.

Embalming, Preparation, and Transport

As embalming gained traction after the Civil War, it became an additional chargeable service. Embalming fees ranged widely: wartime practitioners such as Thomas Holmes charged $100 per body, but postwar civilian undertakers advertised fees between $10 and $30 in urban centers.¹⁹ Preparation of the body—washing, dressing, cosmetic touches—could add several more dollars. Transport costs varied by distance, with rail companies setting their own tariffs for carrying remains; coffin boxes and zinc-lined shipping cases added to the bill.²⁰

Undertakers’ Services and Equipment

The undertaker’s own fee encompassed multiple items: arranging the funeral, supplying a hearse, hiring pallbearers, and providing chairs or decorations for a wake. Price lists from the 1870s indicate that a hearse rental could cost $5–10, while additional carriages for mourners added several dollars each.²¹ Undertakers often bundled these into “complete funeral” packages, encouraging families to think in terms of comprehensive services rather than piecemeal purchases.

Cemetery Fees and Burial Lots

Cemetery records are among the most reliable sources for quantifiable costs. For example, at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, adult burials in the mid-nineteenth century cost $7.²² In Cleveland, Woodland Cemetery charged between $8 and $400 for lots, depending on size and location.²³ At Lake View Cemetery (est. 1869), an in-ground grave could cost $4 in 1870, with larger lots priced by square foot.²⁴ Grave digging, opening, and closing fees added $2–5, depending on soil conditions.

Monuments and Memorialization

Beyond the burial itself lay the enduring cost of memory. Marble headstones in the 1850s could be purchased for $20–50, while granite monuments or obelisks easily exceeded $200.²⁵ Monumental masons advertised in urban newspapers, appealing both to sentiment and to status. Families judged “respectable” funerals not merely by the coffin or ceremony, but by the durability and impressiveness of the monument erected in the cemetery.

Auxiliary Costs: Mourning Dress and Accessories

Finally, households faced social expectations of mourning attire and accessories. Black crepe, veils, gloves, and suits imposed significant additional burdens—particularly on women, for whom extended mourning dress was considered obligatory.²⁶ Middle-class families might spend more on clothing than on the burial itself, while poorer households risked debt to appear properly attired. Newspaper advertisements reveal a thriving trade in “ready-made mourning,” pitched as both affordable and socially necessary.²⁷

Pauper Burials

For those unable to afford even minimal outlays, municipalities or charitable institutions provided pauper burials. In New York, municipal contracts set fixed prices per body—sometimes as little as $2.50 for a pine coffin and trench burial in Potter’s Field.²⁸ While such arrangements relieved financial burden, they carried heavy social stigma, reinforcing cost as a marker of social inequality in death.

Empirical Case Studies and Price Evidence

Overview

The abstractions of undertaker manuals and cemetery bylaws take on sharper clarity when examined through individual case studies. Although the evidence is scattered, probate records, municipal reports, and contemporary newspapers allow us to glimpse the real-world costs borne by families in different regions and classes. These examples highlight both the range of expenditures and the deep inequality embedded in nineteenth-century death care.

Urban versus Rural Variation

Urban centers, with established undertakers and commercial cemeteries, typically imposed higher baseline costs than rural communities. In rural New England or the Midwest frontier, families often relied on neighbors for coffin-making and dug graves themselves, reducing expenses to only a few dollars. By contrast, in cities like New York or Philadelphia, the bundle of services—coffin, hearse, cemetery lot, and undertaker’s fee—could easily total $50 or more by mid-century.²⁹ The gap reflected not only economic differences but also divergent cultural expectations: urban funerals tended to be more elaborate, shaped by competitive consumption and social visibility.

Regional Differentials

Southern funeral records underscore the economic dislocations of slavery and Reconstruction. For enslaved persons, costs were typically borne by owners, and plantation account books record minimal outlays—most often just the lumber for coffins.³⁰ By contrast, elite white families in cities such as Charleston or New Orleans invested heavily in family vaults and marble monuments, expenditures that could surpass $500.³¹ In the Midwest, expanding garden cemeteries like Chicago’s Rosehill or Cleveland’s Woodland marketed graded lots to a growing middle class, with prices that ranged widely but often exceeded the affordability of wage laborers.³²

Cemetery Plot Prices

Cemetery lot books give concrete numerical evidence:

- Calvary Cemetery, Queens: An adult burial in the mid-nineteenth century cost $7.³³

- Woodland Cemetery, Cleveland: Lots were priced between $8 and $400, depending on size and location.³⁴

- Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland (est. 1869): In-ground graves cost $4 in 1870, with larger lots priced by square foot.³⁵

These figures, modest as they may seem, carried real weight. A $20 plot in the 1850s could represent nearly two weeks’ wages for a skilled laborer.³⁶ Cemetery boards, conscious of both revenue and reputation, also imposed “perpetual care” fees by the late century, adding recurring costs to the initial purchase.³⁷

Undertaker Bills and Funeral Accounts

Undertaker ledgers from cities such as Philadelphia and Cleveland, where they survive, record striking variation. A typical mid-century bill might itemize: $15 for a coffin, $5 for hearse rental, $3 for grave digging, and $10 for carriages—totalling around $35.³⁸ By the 1880s, the introduction of caskets, embalming, and more elaborate services pushed standard bills toward $75–100 in many urban centers.³⁹ Probate court filings often list “funeral expenses” as a lump sum; in Massachusetts estates of the 1870s, these ranged from $18 for modest burials to over $120 for wealthier households.⁴⁰

Poverty and Pauper Funerals

At the bottom of the spectrum, municipal reports reveal contracted rates for pauper burials. New York City in the 1860s paid undertakers $2.50–3.00 per body for trench burials at Potter’s Field.⁴¹ In Cleveland, indigent burials were contracted at $5 per body by the 1880s.⁴² These sums covered the most basic coffin and labor, with no provision for memorials or family rites. While relieving financial burden, such burials reinforced social stigma and underscored the economic dimension of respectability in death.

The Burden on Households and Social Implications

Overview

The financial realities of burial bore heavily upon American households in the nineteenth century. Funerals were not only intimate family events but also public performances of respectability, piety, and social standing. The costs involved were therefore more than economic: they represented cultural obligations, moral pressure, and markers of class and race.

Funeral Debt and Credit

Funerals often generated debts. Probate records from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania repeatedly list “funeral expenses” as debts against estates, sometimes paid before any other obligations.⁴³ Undertakers themselves frequently extended credit, trusting families to settle accounts from estate proceeds. In poorer households, debts for coffins, carriages, or cemetery plots lingered for months, sometimes contested in court.⁴⁴ By the late nineteenth century, newspapers occasionally criticized undertakers for predatory practices, accusing them of exploiting grief through inflated fees.⁴⁵

Coping Strategies: Mutual Aid and Insurance

To mitigate costs, working-class families increasingly turned to benevolent societies, fraternal lodges, and church groups that promised modest death benefits. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, for instance, established burial funds in the 1840s to guarantee members at least a coffin and grave.⁴⁶ Burial insurance—offered by commercial firms or through mutual aid societies—grew especially popular after the Civil War, providing payouts of $50–100, roughly the cost of a “respectable” funeral in many cities.⁴⁷ For immigrants and African Americans, ethnic and religious societies offered critical support in securing burial dignity otherwise inaccessible through mainstream institutions.⁴⁸

Differentials by Class, Race, and Gender

The burden of funeral expenses exposed deep social inequities. Wealthier families could afford elaborate ceremonies, while poorer households struggled even to secure a wooden coffin. African American families in both North and South often bore disproportionate costs relative to income, partly due to exclusion from white-controlled cemeteries, which forced them to purchase plots in segregated burial grounds or establish their own.⁴⁹ Women frequently bore the brunt of financial and emotional responsibility, both in organizing rituals and in assuming debts after the death of male wage earners.⁵⁰

Respectability and Social Obligation

The funeral was, in the nineteenth century, an unavoidable public performance of respectability. As social commentators of the time noted, families were judged not only on their moral standing in life but also on how they buried their dead.⁵¹ Failure to provide a “decent” burial risked accusations of neglect or dishonor, even if financial hardship made such expenditures impossible. This moral economy of respectability ensured that many families overspent, indebting themselves in order to avoid social shame.

Municipal and Charitable Burial for the Indigent

Municipal authorities and charitable organizations attempted to address the plight of the poor through publicly funded burials. Cities contracted undertakers to provide pauper funerals at fixed rates, as in New York’s Potter’s Field, where burials cost the city around $2.50–3.00 per body.⁵² Catholic parishes, Protestant charities, and Jewish benevolent societies likewise subsidized burials for impoverished members.⁵³ Yet such provisions were often stigmatized, reinforcing distinctions between “respectable” and “pauper” deaths. For many families, avoiding pauper burial at all costs—financial or otherwise—was itself a primary goal.

Trends over Time: Mid- to Late Nineteenth Century

Overview

The costs of dying in nineteenth-century America did not remain static. Across the century, funerary expenses escalated alongside broader shifts in consumer culture, urban growth, and professionalization. What began as modest, largely domestic rituals by mid-century had become, by the 1890s, highly commercialized and socially codified events.

Price Inflation and Cost Escalation

Funeral expenses rose steadily through the century. Early in the 1800s, a burial might cost a family only a few dollars for a coffin and grave. By the 1870s–80s, the introduction of caskets, embalming, and more elaborate funerary services pushed “respectable” urban funerals into the $75–100 range.⁵⁴ Rising urban land values also made cemetery plots more expensive, with rural cemeteries marketing larger, landscaped lots as symbols of status.⁵⁵ The trend reflects not only inflation but the deliberate commercialization of funerary culture.

Professionalization and Standardization

As undertakers formed trade organizations and published mortuary manuals, funerals became increasingly standardized. Model price lists circulated through journals, establishing norms for coffin prices, embalming fees, and hearse rentals.⁵⁶ By the 1880s, many cities had directories of undertakers, each offering similar “packages” that reinforced industry-wide expectations. This professionalization both stabilized and raised costs, since undertakers could justify higher fees by appealing to “industry standards.”

Competition and Economies of Scale

Yet competition tempered these pressures. In larger cities, undertakers competed on both price and services, advertising “complete funerals” at fixed sums designed to attract middle-class customers.⁵⁷ Some even offered installment plans, anticipating twentieth-century funeral credit systems. The spread of mass-produced caskets, manufactured in industrial centers like Cincinnati, lowered wholesale costs and allowed undertakers to profit through markups.⁵⁸

Shifts in Ritual and Consumer Expectations

The second half of the century witnessed a cultural shift toward more elaborate rituals. Embalming and extended viewing became common in middle-class families, while mourning dress and accessories remained widespread social expectations.⁵⁹ The increasing importance of cemetery monuments likewise transformed cost structures: whereas a modest headstone sufficed earlier in the century, families now invested in obelisks, angels, or granite vaults. Such expenditures reflected not only grief but the pressures of social aspiration.⁶⁰

Critiques, Resistance, and Regulation

The rising costs of funerals did not go unchallenged. Clergy and reformers occasionally condemned what they viewed as wasteful extravagance, urging simpler burials as more in keeping with Christian humility.⁶¹ By the 1890s, some states began regulating embalming practices, cemetery operations, and undertaker licensing, in part to curb abuses.⁶² Despite such critiques, the trend toward commercial funerals proved inexorable, embedding cost ever more deeply into the American experience of death.

Interpretations and Broader Implications

Overview

The costs of dying in nineteenth-century America illuminate broader patterns of consumer culture, household economy, and social order. Beyond their immediate financial strain, funerals and burials reflected transformations in capitalism, urbanization, and cultural identity.

Death and the Commodification of Life

The rising expenses of funerals epitomize the commodification of intimate life events in the nineteenth century. Where once neighbors or kin performed the work of laying out a body and digging a grave, specialized professionals now sold services and goods at standardized prices.⁶³ Funerals became less a communal obligation and more a consumer transaction, mirroring broader trends in industrial capitalism. The “American way of death” was, by century’s end, an industry with its own marketing, trade organizations, and economic incentives.

Household Economics and Sudden Expenditures

For ordinary households, funeral costs stood out as one of the most sudden and non-deferrable expenses they could face. Unlike weddings or property purchases, funerals allowed little time for saving or planning. Probate records reveal that funeral expenses were frequently among the largest immediate cash outlays in a family’s year, sometimes exceeding medical bills.⁶⁴ This unpredictability made mutual aid societies and burial insurance essential to household economic resilience.

Social Stratification and Inequality

Funeral expenditures reinforced class and racial inequalities. The ability to afford a casket, headstone, or cemetery plot signified not just mourning but status. For immigrant and African American communities, burial costs were doubly fraught: exclusion from elite cemeteries often forced them into segregated burial grounds or into forming independent institutions.⁶⁵ Public discourse around “pauper burials” cast poverty as moral failure, stigmatizing families unable to afford even the most basic funerals.⁶⁶

Death, Memory, and Consumer Aspiration

The nineteenth century also saw funerals and monuments become a form of aspirational consumption. Families invested heavily in cemetery lots, elaborate monuments, or mourning attire not only to honor the dead but to situate themselves within a hierarchy of respectability.⁶⁷ The landscapes of garden cemeteries, with their graded lots and ornamental statuary, became spaces where memory intertwined with consumer aspiration.

Death and the Modern State

Finally, the economics of burial intersected with the expansion of municipal and state institutions. Cities contracted undertakers for pauper burials, set health codes for embalming and interment, and regulated cemetery corporations.⁶⁸ In this sense, funerary costs were not merely private burdens but also public concerns, tied to health, order, and social welfare.

Conclusion

The nineteenth century marked a profound transformation in the economic and cultural dimensions of dying in America. What had once been largely a domestic, community-managed process became a commercial enterprise characterized by standardized services, professional undertakers, and escalating costs.

The evidence surveyed in this essay underscores several key findings. First, the cost of death steadily increased, fueled by urban land values, the rise of professional undertaking, and consumer demand for more elaborate rituals. A funeral that might have cost a family less than $10 in 1820 could, by the 1890s, easily exceed $100.⁶⁹ Second, these expenses were not merely economic but social obligations, embedded in a moral economy of respectability: families risked shame if they failed to provide what neighbors deemed a “decent” burial. Third, the burden of funeral costs magnified inequalities—by class, race, and gender—forcing poor families into debt or pauper burial, while the wealthy used cemetery monuments and elaborate funerals to project status.⁷⁰

The long-term implications of this transformation were profound. By the end of the nineteenth century, Americans had come to accept death as a commercialized, professionalized domain, with cost and consumption as inescapable aspects of mourning.⁷¹ The undertaker had become a permanent fixture in urban life; the cemetery, a landscaped stage for memory and aspiration; and the funeral, a moment where private grief intersected with public display.

At the same time, the very visibility of funeral costs sparked critique. Reformers called for simplicity, clergy denounced extravagance, and municipal authorities grappled with the costs of pauper burials. These tensions foreshadowed twentieth-century debates about the “American way of death” and its place within consumer capitalism.⁷²

Ultimately, studying the cost of burial in the nineteenth century allows us to see more than dollars and cents. It reveals how Americans negotiated dignity, obligation, and memory under the pressures of capitalism and inequality. It shows that even in death—perhaps especially in death—the struggle to balance financial means and social expectations was an inescapable part of the American experience.

Appendix

Notes

- “Funeral Practices Through the Ages in America,” Locke Funeral Services blog. lockefuneralservices.com.

- “Undertakers and Hearses,” Clements Library / Death in Early America exhibit. clements.umich.edu.

- Ibid.

- “From Parlors to Slumber Rooms: The Evolution of the 19th Century Funeral,” Remembering A Life blog. rememberingalife.com.

- Ibid.

- “Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws,” Library of Congress blog. blogs.loc.gov.

- “Funeral History in the United States,” Woodvale Cemetery blog. woodvalecemetery.com; also “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. case.edu.

- “Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws,” Library of Congress blog.

- “Funeral History in the United States,” Woodvale Cemetery blog.

- “Thomas Holmes (mortician),” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- Ibid.

- “Funeral History in the United States,” Woodvale Cemetery blog.

- “From Parlors to Slumber Rooms,” Remembering A Life blog.

- “Association of American Cemetery Superintendents,” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- “Coffins to Caskets: The Evolution of the American Funeral,” Civil War Medicine Museum. civilwarmed.org.

- “Fisk Metallic Burial Case,” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- “From Parlors to Slumber Rooms,” Remembering A Life blog.

- “Thomas Holmes (mortician),” Wikipedia.

- “Funeral History in the United States,” Woodvale Cemetery blog.

- “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- “Calvary Cemetery (Queens),” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- “Woodland Cemetery (Cleveland),” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- “Lake View Cemetery,” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org.

- David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 108–12.

- Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Vintage, 2008), 146–52.

- Lori Merish, Sentimental Materialism: Gender, Commodity Culture, and Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 85–90.

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 786.

- Gary Laderman, Rest in Peace: A Cultural History of Death and the Funeral Home in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 18–22.

- Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg, eds., Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 156.

- Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), 2:311–12.

- Sloane, Last Great Necessity, 142–48.

- “Calvary Cemetery (Queens),” Wikipedia.

- “Woodland Cemetery (Cleveland),” Wikipedia.

- “Lake View Cemetery,” Wikipedia.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Historical Wages in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1934), 74–76.

- Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989), 263–65.

- “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- Charles O. Jackson, Passing: The Vision of Death in America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977), 97–101.

- Probate Records, Middlesex County (MA), 1870s, cited in Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 88.

- Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 786.

- Annual Report of the City of Cleveland, 1884, cited in Sloane, Last Great Necessity, 149.

- Probate Records, Middlesex County (MA), 1870s, cited in Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 91–94.

- Sloane, Last Great Necessity, 150.

- Jackson, Passing, 104–06.

- Mark Carnes, Secret Ritual and Manhood in Victorian America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 118–22.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 27.

- Mitch Kachun, First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 202–05.

- Suzanne E. Smith, To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 23–28.

- Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 149–53.

- Jackson, Passing, 97–99.

- Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 786.

- Hasia Diner, A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1880 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 142–45.

- Jackson, Passing, 97–101.

- Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill, 255–60.

- Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 76–82.

- “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- Sloane, Last Great Necessity, 153–55.

- Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 148–52.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 30–33.

- Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 102–05.

- “Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws,” Library of Congress blog.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 18–22.

- Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 87–90.

- Smith, To Serve the Living, 25–30.

- Jackson, Passing, 104–06.

- Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill, 263–70.

- “Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws,” Library of Congress blog.

- Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 88–92.

- Smith, To Serve the Living, 27–31.

- Laderman, Rest in Peace, 23–28.

- Jackson, Passing, 108–12.

Bibliography

Books

- Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Carnes, Mark. Secret Ritual and Manhood in Victorian America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Ellis, Clifton, and Rebecca Ginsburg, eds. Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

- Farrell, James J. Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830–1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Vintage, 2008.

- Jackson, Charles O. Passing: The Vision of Death in America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977.

- Kachun, Mitch. First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Laderman, Gary. Rest in Peace: A Cultural History of Death and the Funeral Home in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Linden-Ward, Blanche. Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989.

- Martineau, Harriet. Retrospect of Western Travel. London: Saunders and Otley, 1838.

- Merish, Lori. Sentimental Materialism: Gender, Commodity Culture, and Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Sloane, David Charles. The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Smith, Suzanne E. To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Historical Wages in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1934.

- Diner, Hasia. A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1880. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Articles, Blogs, and Online Sources

- “Association of American Cemetery Superintendents.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Association_of_American_Cemetery_Superintendents.

- “Calvary Cemetery (Queens).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calvary_Cemetery_%28Queens%29.

- “Coffins to Caskets: The Evolution of the American Funeral.” Civil War Medicine Museum. https://www.civilwarmed.org/coffins-to-caskets/.

- “Evolution of American Funerary Customs and Laws.” Library of Congress Blog. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/09/evolution-of-american-funerary-customs-and-laws/.

- “Fisk Metallic Burial Case.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fisk_metallic_burial_case.

- “From Parlors to Slumber Rooms: The Evolution of the 19th Century Funeral.” Remembering a Life Blog. https://www.rememberingalife.com/blogs/blog/from-parlors-to-slumber-rooms-the-evolution-of-the-19th-century-funeral.

- “Funeral History in the United States.” Woodvale Cemetery Blog. https://woodvalecemetery.com/funeral-history-in-the-united-states/.

- “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. https://case.edu/ech/articles/f/funeral-homes-and-funeral-practices.

- “Funeral Practices Through the Ages in America.” Locke Funeral Services Blog. https://www.lockefuneralservices.com/blog/post/funeral-practices-through-the-ages-in-america.

- “Lake View Cemetery.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_View_Cemetery.

- “Thomas Holmes (mortician).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Holmes_%28mortician%29.

- “Undertakers and Hearses.” Clements Library, Death in Early America exhibit. https://clements.umich.edu/exhibit/death-in-early-america/undertakers/.

- “Woodland Cemetery (Cleveland).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodland_Cemetery_%28Cleveland%29.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.01.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.