The grandeur of Westminster Hall, the symbolism of the Wilton Diptych, and his insistence on ceremonial majesty foreshadowed later developments in Tudor and Stuart monarchy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

When Richard II ascended the English throne in 1377 at the age of ten, he inherited not only the crown of his grandfather Edward III but also the burdens of a kingdom exhausted by war, economic strain, and social upheaval. His minority placed governance in the hands of regency councils dominated by magnates such as John of Gaunt, whose influence fostered deep factionalism.¹ The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, occurring when Richard was only fourteen, provided an early stage on which the young monarch projected a heightened sense of divine mission.² Outwardly calm and commanding in his meeting with the rebels at Smithfield, Richard seems to have internalized the conviction that his kingship was uniquely ordained and sacral in nature.³

Over the course of his reign, this conception of regal authority grew into an absolutist ideology expressed through elaborate ceremonial, artistic patronage, and the cultivation of a court that emphasized magnificence over pragmatism.⁴ Richard’s household expenses ballooned, his largesse flowed disproportionately to favorites such as Robert de Vere and Michael de la Pole, and his insistence on monarchical independence alienated the very nobles upon whom his position depended.⁵ Unpopular taxation, especially in the wake of costly but inconclusive military ventures in France and Ireland, deepened resentment among commons and magnates alike.⁶

The tension between Richard’s vision of sacral monarchy and the political realities of late medieval England culminated in crises that twice threatened his rule. The Lords Appellant movement of 1387–89 temporarily curtailed his power, while his reassertion of absolutist authority in the 1390s provoked Henry Bolingbroke’s challenge and Richard’s ultimate deposition in 1399.⁷ Historians have long debated whether Richard should be remembered primarily as a tyrannical failure or as a misunderstood innovator whose cultural vision was ill-suited to the political structures of his day.⁸ What remains clear is that Richard II’s reign exposes the peril of royal absolutism in an era when consent and cooperation with magnates remained essential to stable governance.

The Child King and the Burden of Inheritance

Richard II’s accession in 1377 was not simply a dynastic succession but a constitutional crisis in miniature. He was a boy of ten inheriting the mantle of his grandfather Edward III, whose long reign had seen both triumphs, such as the early victories of the Hundred Years’ War, and crushing burdens of taxation and military fatigue.⁹ The regency arrangements put in place after Edward’s death reflected both suspicion and necessity: no single magnate was entrusted with outright power. Instead, a council of nobles, led in practice by John of Gaunt, sought to preserve the prerogatives of the crown while curbing the dangers of minority rule.¹⁰ This structure fostered an unstable political environment, with factions emerging around Gaunt, the bishops, and other magnates eager to influence the boy-king’s future.

Richard’s minority unfolded in a context of deep socioeconomic unrest. The Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century had reduced the population by perhaps half, permanently altering the balance of labor and land.¹¹ Tensions between landowners and peasants simmered throughout the 1370s, culminating in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. The revolt, provoked in part by the government’s imposition of a third poll tax within a decade, forced the fourteen-year-old Richard into an unexpected role as political negotiator.12 His famous confrontation at Smithfield, in which he is reported to have declared to the rebels “I am your captain, follow me,” was an extraordinary moment for a monarch still in adolescence.13

That performance left a deep impression. Chroniclers such as Thomas Walsingham suggested that Richard’s composure in the face of danger testified to a precocious sense of divine destiny.¹⁴ Later historians have debated whether this was youthful bravado, careful coaching by councillors, or a genuine glimpse of the king’s self-conception. Either way, the events of 1381 shaped Richard’s political identity. His conviction that monarchy was divinely ordained (and that he, as king, stood above the fractious nobility) would become a hallmark of his later reign.¹⁵ It was precisely this confidence in personal authority, forged in the crucible of minority and revolt, that predisposed Richard to a vision of kingship both elevated and inflexible.

The Cultivation of Regal Authority

Richard II’s political imagination was shaped not only by the turbulence of his minority but also by a profound sense of kingship as a sacred office. Unlike his grandfather Edward III, whose authority rested on military achievement and the loyalty of a broad coalition of nobles, Richard increasingly leaned on ritual, spectacle, and symbolism to bolster his rule.¹⁶ This emphasis reflected both his personal temperament and the influence of continental models of sacral monarchy, especially from France, where Valois kings were already experimenting with the language of divine ordination and ritual magnificence.¹⁷

Ceremony became central to Richard’s assertion of power. He staged elaborate processions, sponsored liturgical innovations, and cultivated a public image that elevated him far above the baronage.¹⁸ His coronation in 1377 was a particularly significant moment: the pageantry was deliberately designed to underscore the sanctity of the crown and the personal holiness of the child-king.¹⁹ As Nigel Saul has argued, Richard took these lessons of theatrical authority to heart, developing over the following decades a style of governance in which performance and sacral imagery substituted for the more pragmatic mechanisms of negotiation and conciliation.²⁰

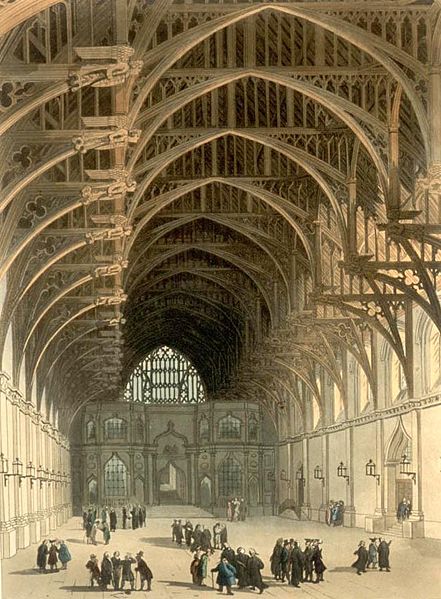

Art and architecture reinforced this vision. Richard patronized the rebuilding of Westminster Hall with its celebrated hammer-beam roof, commissioned the Wilton Diptych (a devotional panel depicting the king in the presence of the Virgin and Christ), and poured resources into the cult of St. Edward the Confessor.²¹ These acts were not mere aesthetic indulgences but conscious attempts to cast Richard as a divinely favored monarch whose authority derived from God rather than the shifting alliances of the nobility.²² To many observers, however, the grandeur verged on arrogance: the king’s insistence on being addressed in quasi-sacral terms, such as “your majesty” (a novelty in England), grated against the traditions of baronial parity.²³

This transformation of royal image alienated many among the “old guard” nobility. Where earlier kings had cultivated bonds of familiarity with their magnates, Richard erected barriers of ceremony and exclusivity.²⁴ By insisting that the monarchy was a sacred institution that transcended negotiation, he sought to eliminate the horizontal bonds that had long sustained Plantagenet kingship. But this vision, radical for its time, contained within it the seeds of downfall. For while ritual and magnificence could project divine authority, they could not by themselves substitute for the military victories, fiscal restraint, or political coalition-building that secured legitimacy in fourteenth-century England.²⁵

Pageantry, Luxury, and the Courtly Sphere

Richard II’s court was not merely a seat of governance but a stage upon which the ideology of sacral monarchy was performed daily. The king’s household expenses expanded dramatically, reflecting both his desire to embody royal magnificence and his conviction that the projection of grandeur was itself a form of political authority.²⁶ Court festivals, tournaments, and processions were orchestrated with a precision and extravagance previously unseen in England.²⁷ For Richard, such spectacles were not ornamental excess; they were integral to the cultivation of obedience and awe.

Yet to the older nobility, reared in the martial ethos of Edward III’s wars, this emphasis on pageantry smacked of decadence.²⁸ Richard surrounded himself with courtiers and companions of relatively modest lineage, men who appreciated and benefited from his patronage but lacked the established pedigrees of the realm’s great families.²⁹ The household thus became a flashpoint for resentment, as traditional aristocrats watched royal patronage flow disproportionately to newcomers while they themselves were excluded from favor.

Architecture and material culture further accentuated the divide. Richard invested heavily in rebuilding royal residences, most notably Westminster Hall and the palace at Sheen, where opulence was meant to symbolize not only his personal taste but also the majesty of monarchy.³⁰ The Wilton Diptych, commissioned late in his reign, provides perhaps the most vivid example: it depicts Richard kneeling before the Virgin and Child, attended by English saints, a visual theology of kingship in which the monarch appears as Christ’s chosen vassal.³¹ To Richard, such imagery underlined his unique, God-given role; to critics, it embodied an unsettling arrogance that blurred the line between divine and human authority.

Contemporaries did not fail to link such magnificence to financial strain.³² Maintaining an enlarged household, paying for costly artistic projects, and hosting elaborate ceremonies required steady revenue, revenue raised not from victories abroad or trade expansion but from increasingly heavy taxation at home.³³ Thus, the king’s pageantry, intended to sanctify his rule, paradoxically deepened the alienation of commons and magnates alike. By the late 1380s, Richard’s magnificence had ceased to be interpreted as grandeur and was instead seen as extravagance: a lifestyle that drained the kingdom for the sake of royal vanity.³⁴

Inner Circle and Favoritism

If Richard II’s magnificence projected the grandeur of monarchy, it was his circle of intimates who reaped its material benefits. Chief among them were Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and Michael de la Pole, who rose from a merchant’s son to Earl of Suffolk and Chancellor of England.³⁵ Both men were lavishly rewarded with titles, offices, and grants of land, provoking accusations that Richard was subverting the traditional order of nobility.³⁶ Their prominence symbolized a redistribution of favor that bypassed the old aristocracy in favor of personal loyalty, intensifying resentment among the realm’s most powerful families.

Richard’s reliance on favorites carried political consequences far beyond court gossip. De la Pole’s appointment as chancellor in 1383 was met with hostility in Parliament, where his commoner background and perceived incompetence were condemned.³⁷ De Vere’s elevation to Duke of Ireland in 1386 further scandalized the nobility, not only because of the unprecedented dignity bestowed but also because it coincided with the king’s unwillingness to heed baronial counsel in matters of war and finance.³⁸ In the eyes of many magnates, Richard was not merely rewarding companions but dismantling the balance of noble hierarchy upon which Plantagenet authority rested.

The backlash culminated in the crisis of the Lords Appellant (1387–89).³⁹ A coalition of leading magnates (including the Duke of Gloucester, the Earl of Arundel, and the Earl of Warwick) rose against Richard’s household and secured the condemnation of his favorites in the Merciless Parliament of 1388.⁴⁰ De Vere fled abroad, de la Pole was impeached, and others of Richard’s inner circle were executed. The purge revealed not only noble fury at royal favoritism but also the fragility of Richard’s political base: absent the loyalty of his courtiers, he lacked the support of traditional magnates or commons.⁴¹

The events of 1387–89 left scars that Richard never forgave. Though restored to power by the early 1390s, he carried with him a determination to punish those who had humiliated him and destroyed his circle of companions.⁴² The experience deepened his conviction that monarchical authority must stand above aristocratic interference. Yet in doing so, Richard further entrenched the very practices (excessive reliance on favorites, personal vengeance, and disregard for noble consent) that had provoked the crisis in the first place.⁴³

Fiscal Mismanagement and Taxation

Richard II’s vision of kingship, grounded in magnificence and personal authority, required financial resources far beyond the crown’s ordinary revenues. To maintain his enlarged household, sponsor artistic and architectural projects, and sustain intermittent military campaigns, Richard turned repeatedly to extraordinary taxation.⁴⁴ This fiscal reliance on Parliament created a paradox: the king demanded funds to reinforce his regal independence, yet by seeking them he acknowledged a political dependence he loathed.

The most notorious example of fiscal strain was the series of poll taxes levied between 1377 and 1381.⁴⁵ Though Richard was still a minor, the memory of these taxes, especially the disastrous 1381 levy that sparked the Peasants’ Revolt, lingered throughout his reign, associating his government with financial oppression. Later in the 1380s, repeated requests for subsidies to fund French and Irish campaigns met mounting resistance.⁴⁶ Parliamentarians balked at granting money for ventures that yielded little military return, especially when royal expenditure on the household seemed unchecked.

Richard’s fiscal policies also included the controversial practice of “blank charters,” in which communities and individuals were compelled to sign documents permitting royal officials to fill in the financial demands later.⁴⁷ Though framed as a means of raising revenue efficiently, the practice was widely perceived as extortion. Combined with frequent forced loans, it eroded trust between king and subjects, reinforcing the image of Richard as a ruler willing to bleed the realm for personal grandeur.⁴⁸

The political fallout of such taxation was profound. Discontented commons aligned with disaffected magnates in criticizing Richard’s wastefulness, forming an unusual coalition of opposition across social ranks.⁴⁹ At moments such as the Wonderful Parliament of 1386, financial grievances translated directly into political constraint: Parliament impeached Michael de la Pole and attempted to impose oversight on royal finances.⁵⁰ Richard’s refusal to concede in such moments only deepened his alienation. By the 1390s, he sought to finance his household and ambitions not through negotiation but through coercion, thereby radicalizing his absolutist posture while depleting the very political capital that monarchy required.⁵¹

Beyond its immediate financial impact, Richard’s fiscal policy reshaped perceptions of kingship itself. The Plantagenet tradition, though often hard on taxpayers, had typically justified extraordinary levies by appealing to national defense: wars in France, campaigns in Scotland, or the protection of the realm from invasion.⁵² Richard, by contrast, blurred the line between the needs of the crown and the desires of the king. Household expenditure and court luxury were presented as indistinguishable from the defense of England, as though the maintenance of magnificence were itself a form of safeguarding the kingdom.⁵³ This conflation, however, proved politically corrosive. It alienated the commons, who saw their contributions feeding pageantry rather than campaigns, and it unsettled the nobility, who feared that the ancient partnership of king and magnates was being supplanted by a model of monarchy accountable to no one but itself.⁵⁴

Military Failures and the Limits of Authority

If Richard II aspired to embody sacral monarchy, he conspicuously failed to achieve the military successes that had legitimized his Plantagenet predecessors. Edward III’s reign had been defined by victories at Crécy and Poitiers, achievements that buttressed his lavish court and won him enduring respect from the nobility. Richard, by contrast, presided over inconclusive campaigns that drained resources without delivering glory.⁵⁵

The French war was the clearest theater of disappointment. Though Parliament regularly voted subsidies for expeditions, Richard often preferred negotiation to action, pursuing truces with France that many nobles interpreted as dishonorable retreats.⁵⁶ His 1396 marriage to Isabella of Valois, sealed as part of a twenty-eight-year truce, was intended to project statesmanship but instead underscored perceptions of weakness.⁵⁷ To a nobility still imbued with the chivalric ethos, Richard’s diplomacy seemed an abdication of the martial duty that justified taxation and bound king to realm.

His Irish campaigns proved no more successful. In 1394 and again in 1399, Richard personally led forces to Ireland, hoping to demonstrate military vigor and extend royal control.⁵⁸ Both expeditions were costly and logistically complex; though he won some submissions from Irish lords, the gains evaporated once his forces withdrew.⁵⁹ Worse still, the second campaign coincided with Henry Bolingbroke’s return from exile, leaving Richard absent and politically vulnerable at the very moment his throne required his presence.⁶⁰

Richard’s military shortcomings carried political consequences beyond the battlefield. They deprived him of the symbolic victories that could have justified his courtly magnificence and fiscal demands.⁶¹ Without campaigns that united king and nobility in shared purpose, taxation came to be seen as exploitation, not sacrifice. Magnates who might have rallied to a triumphant king instead doubted his competence and commitment to their values. In this sense, Richard’s failure to embody the warrior-king archetype not only tarnished his personal reputation but also undermined the ideological foundations of his monarchy.⁶²

Political Collapse and Deposition

The crises of the late 1380s had left Richard II chastened but unrepentant. When he regained authority in the early 1390s, he carried with him a determination to punish those who had humiliated him during the Lords Appellant revolt.⁶³ Rather than seek reconciliation, Richard embarked on a program of vengeance and authoritarian consolidation, a course of action that widened his isolation and prepared the ground for his downfall.

Between 1397 and 1399, Richard orchestrated the destruction of his former opponents.⁶⁴ Gloucester, Arundel, and Warwick, once among the Lords Appellant, were arrested and tried, with Arundel executed and Gloucester dead in suspicious circumstances. Parliament was purged, and Richard’s supporters filled key positions in government.⁶⁵ In these years, the king seemed to achieve what he had long desired: near-absolute control of the realm, unencumbered by magnate oversight. Yet this apparent triumph only deepened fears among the nobility that Richard intended to transform the monarchy into a tyranny.

Richard’s methods betrayed his absolutist leanings. He used charges of treason liberally, deployed a loyalist Parliament (the so-called “Revenge Parliament” of 1397) to legitimate his vendettas, and demanded increasingly deferential forms of address.⁶⁶ The trappings of sacral monarchy that had once been theatrical flourishes now became ominous symbols of autocracy. Magnates who had tolerated Richard’s pageantry in the 1380s now saw in it the mask of a despot determined to subvert the balance of the realm.

The final crisis was sparked less by ideology than by dynastic politics. In 1398 Richard exiled Henry Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt, after a quarrel with Thomas Mowbray.⁶⁷ When Gaunt died in 1399, Richard seized Bolingbroke’s inheritance of the Duchy of Lancaster, violating established custom and confirming fears that no noble property was secure.⁶⁸ Richard then embarked on his second Irish expedition, leaving England politically exposed. Bolingbroke seized the opportunity to return, initially claiming only his Lancastrian rights but quickly attracting wide support from magnates alienated by Richard’s governance.⁶⁹

Richard’s collapse was swift. By the time he returned from Ireland, Bolingbroke had secured London and much of the nobility. Deserted by allies and unable to muster support, Richard surrendered in August 1399.⁷⁰ He was compelled to abdicate in favor of Bolingbroke, who was crowned Henry IV. Later imprisoned at Pontefract Castle, Richard died in early 1400, almost certainly by starvation or murder.⁷¹ His deposition was not simply the fall of a monarch but the culmination of decades of tension between a vision of absolute, sacral kingship and the entrenched realities of aristocratic consent. Richard’s reign demonstrated that magnificence without military success, and authority without coalition, could not sustain monarchy in late medieval England.⁷²

Legacy and Historiographical Perspectives

The deposition of Richard II in 1399 cast a long shadow over his reputation. Contemporary chroniclers, many of whom were aligned with the new Lancastrian regime, painted Richard as a tyrant whose extravagance, favoritism, and cruelty had justified his removal.⁷³ Thomas Walsingham, writing in the early fifteenth century, emphasized Richard’s arrogance and wastefulness, portraying him as a monarch who squandered England’s wealth on vanity.⁷⁴ Such accounts hardened into a narrative of failure that shaped both political memory and literary representation, most famously in Shakespeare’s Richard II, which dramatized the king as a tragic figure undone by weakness and self-indulgence.⁷⁵

Modern scholarship has sought to complicate this portrait. Beginning in the twentieth century, historians such as May McKisack and Anthony Tuck underscored Richard’s political missteps but also highlighted the structural difficulties he inherited: fiscal exhaustion, aristocratic factionalism, and the aftershocks of the Black Death.⁷⁶ Nigel Saul’s magisterial biography, while critical of Richard’s authoritarian tendencies, nevertheless depicts him as a monarch with a coherent vision of kingship, one rooted in sacral monarchy and cultural patronage rather than the military ethos of his predecessors.⁷⁷ More recent studies have suggested that Richard’s reign represents an experiment in redefining monarchy, an attempt to elevate the crown above the compromises of baronial politics, albeit one fatally out of step with the realities of fourteenth-century England.⁷⁸

Historiographical debate has also engaged with Richard’s cultural achievements. The Wilton Diptych, the rebuilding of Westminster Hall, and the cultivation of court ceremony are now often interpreted as part of a broader project to craft an aesthetic of monarchy.⁷⁹ Rather than mere extravagance, these works articulated a theological vision of kingship that influenced later monarchs, particularly the Tudors, who similarly harnessed spectacle to consolidate power.⁸⁰ In this sense, Richard may be seen as a forerunner of Renaissance kingship, a monarch whose political failure belied his cultural innovation.

Ultimately, Richard II’s legacy is defined by paradox. To some, he remains a failed king, deposed for arrogance and incompetence. To others, he appears as a visionary who attempted to reimagine the monarchy in ways that anticipated later developments but could not succeed in his own time.⁸¹ His reign thus serves as a case study in the tension between political structures and personal ideology: a reminder that magnificence without coalition, and authority without consent, rarely endure.

Conclusion

Richard II’s reign illustrates both the possibilities and perils of kingship in late medieval England. Ascending the throne as a child, he came to identify his rule with a sacral and absolute conception of monarchy, one that sought to elevate the crown above the messy compromises of aristocratic politics.⁸² This vision found expression in court pageantry, architectural patronage, and ceremonial grandeur, but it also alienated the nobility and commons alike, who saw magnificence not as sanctity but as excess. His reliance on favorites, his fiscal exactions, and his inability to secure military victories deprived him of the legitimacy that earlier Plantagenet kings had enjoyed.

Richard’s political collapse in 1399 was not inevitable, but it was the logical outcome of his governing style. By pursuing vengeance against the Lords Appellant, expropriating Bolingbroke’s inheritance, and conflating the needs of the monarchy with the desires of the monarch, Richard eroded the networks of support upon which royal power depended.⁸³ His deposition confirmed a central truth of medieval politics: that kingship in England, for all its sacral pretensions, could not function as an autocracy. It required negotiation, coalition, and a shared sense of purpose with magnates and commons.

Yet Richard’s cultural and ideological legacy proved more enduring than his political authority. The grandeur of Westminster Hall, the symbolism of the Wilton Diptych, and his insistence on ceremonial majesty foreshadowed later developments in Tudor and Stuart monarchy.⁸⁴ In this sense, Richard II was a monarch out of season: a visionary who anticipated the theatrical politics of the Renaissance but whose absolutist style was anachronistic in a fourteenth-century world still dominated by aristocratic consensus.

Richard’s reign thus stands as a cautionary tale. His life demonstrates the dangers of confusing divine imagery with practical governance, of mistaking pageantry for legitimacy, and of elevating personal vision above political necessity. But it also invites us to consider monarchy as a dynamic institution, one that, in Richard’s hands, briefly gestured toward a future he could not inhabit.⁸⁵

Appendix

Footnotes

- Nigel Saul, Richard II (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 34–39.

- Anthony Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy: The Lords Appellant under Richard II (London: Routledge, 1971), 12–15.

- Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 1397–1400: The Reign of Richard II (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), 6–8.

- Saul, Richard II, 198–205.

- May McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 1307–1399 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 510–13.

- Michael Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399 (Stroud: Sutton, 1999), 45–49.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 178–85.

- Saul, Richard II, 512–18; W. Mark Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” in Richard II: The Art of Kingship, ed. Anthony Goodman and James L. Gillespie (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 3–20.

- Saul, Richard II, 23–27.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 10–11.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 483–85.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 39–41.

- Saul, Richard II, 42.

- Thomas Walsingham, Historia Anglicana, ed. Henry T. Riley, Rolls Series, vol. 1 (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863), 454–55.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 5–6.

- Saul, Richard II, 198–205.

- W. Mark Ormrod, Political Life in Medieval England, 1300–1450 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995), 122–24.

- Saul, Richard II, 212–15.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 7.

- Saul, Richard II, 218–22.

- Dillian Gordon, The Wilton Diptych (London: National Gallery Publications, 1993), 14–18.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 9–12.

- Saul, Richard II, 229–30.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 35–37.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 510–12.

- Saul, Richard II, 240–43.

- Chris Given-Wilson, The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity: Service, Politics and Finance in England, 1360–1413 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 89–92.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 511.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 42–45.

- Saul, Richard II, 250–52.

- Gordon, The Wilton Diptych, 21–24.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 53–55.

- Given-Wilson, The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity, 107–10.

- Saul, Richard II, 260–63.

- Saul, Richard II, 266–68.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 514–16.

- Anthony Tuck, Richard II and the English Nobility (London: Edward Arnold, 1973), 56–58.

- Saul, Richard II, 272–74.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 103–08.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 12–15.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 61–64.

- Saul, Richard II, 290–94.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 13–15.

- Saul, Richard II, 310–14.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 487–89.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 78–81.

- Given-Wilson, The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity, 145–48.

- Saul, Richard II, 325–27.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 60–63.

- Ormrod, Political Life in Medieval England, 126–27.

- Saul, Richard II, 330–34.

- Tuck, Richard II and the English Nobility, 74–76.

- Saul, Richard II, 336–38.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 518–20.

- Saul, Richard II, 340–44.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 77–79.

- Saul, Richard II, 355–58.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 97–101.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 26–29.

- Saul, Richard II, 370–73.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 523–25.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 15–17.

- Saul, Richard II, 385–89.

- Goodman, The Loyal Conspiracy, 163–66.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 37–40.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 17–18.

- Saul, Richard II, 400–04.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 527–28.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 134–37.

- Saul, Richard II, 415–18.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 58–60.

- Saul, Richard II, 420–23.

- Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 65–67.

- Walsingham, Historia Anglicana, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1864), 188–90.

- William Shakespeare, Richard II, ed. Charles R. Forker, Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (London: Bloomsbury, 2002), Introduction, 1–5.

- McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 530–32; Tuck, Richard II and the English Nobility, 142–44.

- Saul, Richard II, 510–15.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 18–20.

- Gordon, The Wilton Diptych, 25–28.

- Saul, Richard II, 522–24.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 162–65.

- Saul, Richard II, 525–28.

- Bennett, Richard II and the Revolution of 1399, 170–72.

- Gordon, The Wilton Diptych, 30–32.

- Ormrod, “The Personal Rule of Richard II,” 20.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Michael. Richard II and the Revolution of 1399. Stroud: Sutton, 1999.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. Chronicles of the Revolution, 1397–1400: The Reign of Richard II. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity: Service, Politics and Finance in England, 1360–1413. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Gordon, Dillian. The Wilton Diptych. London: National Gallery Publications, 1993.

- Goodman, Anthony. The Loyal Conspiracy: The Lords Appellant under Richard II. London: Routledge, 1971.

- McKisack, May. The Fourteenth Century, 1307–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959.

- Ormrod, W. Mark. Political Life in Medieval England, 1300–1450. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

- Ormrod, W. Mark. “The Personal Rule of Richard II.” In Richard II: The Art of Kingship, edited by Anthony Goodman and James L. Gillespie, 3–20. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

- Saul, Nigel. Richard II. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Edited by Charles R. Forker. Arden Shakespeare, Third Series. London: Bloomsbury, 2002.

- Tuck, Anthony. Richard II and the English Nobility. London: Edward Arnold, 1973.

- Walsingham, Thomas. Historia Anglicana. Edited by Henry T. Riley. 2 vols. Rolls Series. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863–64.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.