The Cohen Plan stands as a striking illustration of how fragile democratic institutions can be subverted by the deliberate manufacture of fear.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

On 30 September 1937, the Brazilian government announced that the Armed Forces had “discovered” a secret communist plot to overthrow the state, foment strikes, burn public buildings, and depose the existing order. Known as the Plano Cohen (Cohen Plan), the document was immediately wielded as a casus belli to justify sweeping measures: the suspension of constitutional guarantees, the closure of Congress, cancellation of elections, and the concentration of power in the hands of President Getúlio Vargas. Forty days later, on 10 November, Vargas formally instituted the Estado Novo, an authoritarian regime that would last until 1945.1

Historians now concur that the Cohen Plan was a forgery, crafted by military and integralist actors to manufacture a crisis that legitimized the self-coup.2 For decades, however, the regime concealed or tolerated the lie; even among the conspirators, later accounts and conflicting testimonies obscured precise attribution of responsibility.3 Thus, the Cohen Plan stands as one of the most infamous falsifications in Brazilian political history and a paradigmatic case of how “manufactured threats” can be deployed to dismantle democracy.

Beyond sensationalism, the affair demands serious analysis, for it speaks directly to broader themes central to the study of authoritarianism: the role of propaganda and conspiracy, the fragility of institutional restraints under crisis discourse, the complicity of elites and the press, and the genealogy of anti-communist imaginaries in Brazilian political culture.

In what follows, I argue that the Cohen Plan was not an accidental misstep but a deliberate intervention by integralist and military actors seeking a political justification for dictatorial power. Its “discovery” narrative was carefully staged, enabling Vargas and his allies to frame themselves as defenders of order rather than usurpers. The institutional and media environment of Brazil in the 1930s (including preexisting fears of communism, weak party structures, and a submissive press) allowed the forgery to be accepted with minimal skepticism.

The coup’s success underscores how authoritarian consolidation depends as much on producing legitimacy as on wielding force. The lingering uncertainty about authorship and the post-facto contestations reveal how the memory of a forgery can itself become a site of political struggle, shaping Brazilian political imaginaries long beyond the Vargas era.

To investigate these claims, Section II situates the Cohen Plan in its political and intellectual context: the 1930s in Brazil, the legacy of the 1935 Intentona Comunista, and the rise of integralism and anti-communist ideology. Section III examines the creation of the Cohen Plan: its authorship, partial dissemination, and the crafting of its “discovery.” Section IV traces its reception and deployment: how the press, Congress, and the executive responded, culminating in the self-coup and imposition of the Estado Novo. Section V turns to the later unraveling of the forgery: post-1945 confessions, memoirs, archival resistance, and historiographic debates. Section VI offers theoretical reflection: comparisons with other “manufactured crises,” the role of conspiracy discourse in legitimation, and the longer legacies of the Cohen Plan in Brazilian political culture. Finally, Section VII draws together the implications for understanding authoritarian transitions and suggests avenues for further research.

By interlacing archival sources, contemporaneous press accounts, memoirs, and secondary scholarship, this study seeks not only to reconstruct the Cohen Plan saga but also to reflect on why, and how, a false document could wield such power. The story of the Cohen Plan is not merely a footnote in Brazilian history; it is a warning about the fragility of democratic institutions when truth is weaponized.

Historical Context: Brazil in the 1930s

The political turbulence of Brazil in the 1930s formed the essential backdrop against which the Cohen Plan acquired plausibility. Getúlio Vargas had come to power in 1930 through a coup d’état that ousted the Old Republic’s café com leite politics, dominated by the alternating control of São Paulo and Minas Gerais elites.4 His seizure of power was justified in part as a corrective to oligarchic rule, but from the outset it reflected the military’s willingness to arbitrate the political order.5

By 1934, a new constitution was promulgated, establishing a façade of liberal democracy. Yet the arrangement was precarious: Vargas was elected indirectly by the Constituent Assembly, and the balance of power between federal authority, regional elites, and the Armed Forces remained uncertain.6 Party structures were weak, factionalism endemic, and political legitimacy fragile.

A pivotal moment came with the failed communist uprising of November 1935, known as the Intentona Comunista. Inspired by the Comintern and led by members of the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), the rebellion erupted among segments of the military in Natal, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro. Although swiftly suppressed, the uprising fueled an enduring sense of crisis.7 For conservative elites, the specter of Bolshevik revolution in Brazil seemed suddenly plausible.8 The government responded with intensified repression, mass arrests, and a propaganda campaign that kept alive the “red menace” long after the insurrection had collapsed.9

Simultaneously, Brazil witnessed the rapid growth of the Ação Integralista Brasileira (AIB), a movement modeled on European fascism. Led by Plínio Salgado, the Integralists donned green shirts, invoked corporatist ideology, and denounced liberalism and communism alike.10 The AIB attracted tens of thousands of members, including not only disaffected elites but also segments of the middle class, clergy, and students. Its fusion of nationalism, Catholicism, and anti-communism resonated widely in a climate of uncertainty.11 Although the Integralists never achieved power directly, their ideological framework helped legitimize authoritarian solutions to Brazil’s political instability.

By 1937, Brazil’s constitutional order stood at a crossroads. Vargas’s legal mandate was set to expire with the presidential election scheduled for January 1938. Multiple candidates had emerged, but Vargas himself had not openly declared his intention to step down. Congress, weary of extending the “state of war” decrees instituted after 1935, resisted granting new emergency powers.12 The moment was ripe for a manufactured crisis: elites were anxious, communism remained a specter, and the president sought to prolong his hold on power. In this tense atmosphere, the Cohen Plan appeared not as an absurd fabrication, but as confirmation of what many already feared.

The Creation of the Cohen Plan

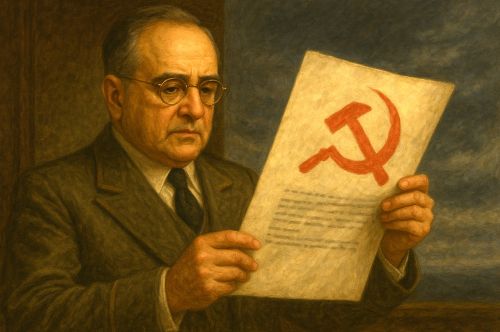

The Cohen Plan was born not out of communist circles but within the ranks of Brazil’s radical right. Its author was Captain Olímpio Mourão Filho, a member of the Ação Integralista Brasileira and an officer in the Brazilian Army.13 Mourão later admitted that he had drafted the document as a speculative exercise or “simulation” of how communists might attempt to seize power.14 Whether conceived as an internal training tool or as propaganda, the text contained lurid details of planned strikes, assassinations, and the destruction of churches and schools.15

The choice of the name “Cohen” was itself symbolic and conspiratorial. Although ostensibly a reference to Béla Kun, the Hungarian communist leader of Jewish origin, the surname carried clear anti-Semitic connotations that resonated with integralist and right-wing rhetoric.16 By framing the conspiracy as “foreign” and “Jewish-Bolshevik,” the Plan tapped into broader fascist discourses circulating not only in Brazil but across the interwar world.17

Once written, the Plan moved rapidly beyond its author’s desk. It reached the hands of General Pedro Aurélio de Góis Monteiro, the powerful chief of the Army General Staff and a staunch ally of Vargas.18 Góis Monteiro, along with War Minister Eurico Gaspar Dutra, saw in the document a golden opportunity to persuade Congress and the public of an imminent communist threat. Instead of clarifying its fictional nature, they chose to treat it as evidence of a genuine conspiracy.19

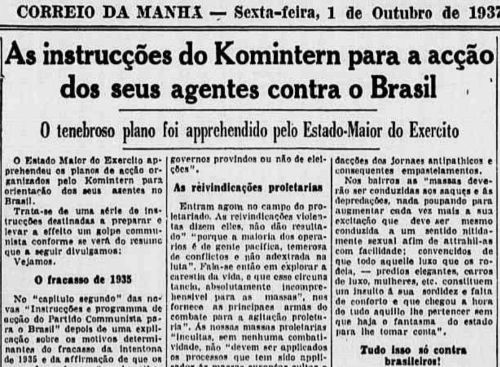

The government deliberately staged its “discovery.” In late September 1937, only a section of the document, Chapter II, was released publicly.20 This selective publication heightened its sensationalism: the excerpt vividly described revolutionary violence, mass arson, and civilian massacres. Presented over national radio broadcasts and splashed across newspapers, the Plan’s contents were read as if they had been seized directly from communist headquarters.21

The orchestration of the Cohen Plan thus reflects a careful strategy. By amplifying fear at precisely the moment Congress debated whether to extend emergency powers, the Vargas regime constructed a pretext for authoritarian measures. The forgery worked not because of its intrinsic plausibility, many of its details bordered on the fantastical, but because it confirmed the preexisting anxieties of a society haunted by the 1935 uprising and primed to believe in perpetual subversion.22

Reception, Legitimization, and Coup Execution

Media and Public Opinion

The dissemination of the Cohen Plan through radio and newspapers ensured that its impact was immediate and widespread. Vargas’s government used the Hora do Brasil, the official nightly broadcast, to dramatize the Plan’s contents.23 Major newspapers reproduced excerpts uncritically, amplifying the sense of urgency.24

Only a handful of journalists and intellectuals raised doubts about its authenticity; for most of the press, the document fit too neatly into the prevailing anti-communist narrative to warrant skepticism.25 Public opinion, long conditioned by the specter of the 1935 uprising, responded with fear rather than disbelief.

Congressional Maneuvers

The Plan’s greatest utility was political. Vargas and his ministers presented it to Congress as definitive proof of an imminent threat, demanding the renewal of the “state of war” decree for an additional ninety days.26 In a climate of fear, the measure passed despite the reluctance of some legislators who sensed exaggeration.27 The Plan thus enabled Vargas to obtain emergency powers without openly declaring a coup. Yet the maneuver also revealed the subordination of representative institutions: Congress ratified measures that effectively prepared the ground for its own dissolution.

When dissenting voices emerged within the cabinet, such as Minister of Justice José Carlos de Macedo Soares and Minister of Agriculture Odilon Duarte Braga, they were swiftly dismissed.28 The expulsions reinforced the consolidation of a pro-coup inner circle dominated by Góis Monteiro, Dutra, and Francisco Campos, the jurist tasked with drafting the new authoritarian constitution.29

The Self-Coup of November 1937

On 10 November, Vargas moved decisively. Surrounded by loyal military officers, he announced the dissolution of Congress, cancellation of the scheduled presidential election, and the promulgation of a new constitution, the so-called Polaca, modeled in part on Poland’s 1937 corporatist charter.30 The new order vested sweeping powers in the executive: censorship, suspension of habeas corpus, direct control of the press, and the prohibition of political parties.31 The Estado Novo was thus born, cloaked in the legitimacy manufactured by the Cohen Plan.

Consolidation of the Estado Novo

Once in place, the regime deepened authoritarian controls. All political parties, including the Integralists, were banned.32 Civil liberties were curtailed, strikes prohibited, and opposition leaders jailed or forced into exile.33 Propaganda emphasized Vargas as the “Father of the Poor,” fusing authoritarian paternalism with corporatist ideology.34 In retrospect, the Cohen Plan served as the enabling fiction for this transformation: by legitimizing a fabricated state of emergency, it allowed Vargas to claim necessity rather than ambition as the basis for dictatorship.

The Fraud Unmasked and Post-Factum Confessions

Silence During the Estado Novo

During the Estado Novo itself, the authenticity of the Cohen Plan was rarely challenged in public. State censorship ensured that doubts were suppressed, while propaganda continued to present the forgery as proof of Vargas’s vigilance.35 Military leaders such as Góis Monteiro never contradicted the official narrative, even if privately they acknowledged its dubious origins.36 The Plan thus operated less as a text than as a myth, a justification that no longer required scrutiny once authoritarian rule had been secured.

Post-1945 Disclosures

The fall of Vargas in 1945 transformed the status of the Cohen Plan. In a freer political climate, questions of responsibility and authorship resurfaced. General Góis Monteiro, by then a central figure in Brazil’s military establishment, claimed he had always known the document was false but had used it to protect national security.37 His retrospective justification attempted to preserve his own reputation while framing the Plan as a “necessary lie.”

More damaging were the revelations of Captain Olímpio Mourão Filho, the Plan’s original author. In memoirs published decades later, Mourão admitted that he had composed the text as a hypothetical scenario, not an actual communist blueprint.38 He accused his superiors of deliberately misusing his draft to fabricate a crisis. Yet even Mourão’s account is difficult to parse: his later political career, which included leading the military uprising that initiated the 1964 coup, casts doubt on the sincerity of his self-portrayal as a mere instrument of others’ designs.39

Conflicting Testimonies and Shifting Blame

The multiplicity of accounts after 1945 generated contradictions. Some military figures insisted they had been deceived; others justified the forgery as a legitimate means of preserving order.40 Civilian politicians who had supported Vargas sought to minimize their complicity, claiming ignorance of the document’s fabrication.41 This atmosphere of mutual recrimination ensured that the historical truth of the Cohen Plan remained entangled in political battles well beyond its immediate moment.

Historiographic Reckonings

Historians writing in the postwar decades have treated the Cohen Plan as emblematic of authoritarian manipulation. Moacir Werneck de Castro’s Plano Cohen e Estado Novo (1967) provided one of the earliest sustained critiques, situating the forgery within the broader dynamics of Vargas’s consolidation of power.42 Subsequent scholarship has emphasized both the centrality of anti-communist discourse and the complicity of elites in legitimizing the fraud.43 The Cohen Plan is thus not only a historical artifact but also a case study in how a forged document can shape political reality, long after its falsity is revealed.

Interpretation and Theoretical Reflections

Manufactured Crises and “False Flags”

The Cohen Plan exemplifies what scholars have termed a “manufactured crisis,” a deliberate fabrication designed to justify extraordinary political measures. Similar tactics can be identified elsewhere: the Reichstag Fire of 1933 in Germany, widely exploited by the Nazis to crush communist opposition, or the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a forged text used internationally to fuel anti-Semitic and authoritarian discourses.44 These comparisons reveal that the Cohen Plan was not an isolated aberration but part of a broader repertoire of interwar authoritarian strategies.

Anti-Communism as Discursive Resource

At the heart of the Plan’s effectiveness was the ideological potency of anti-communism. In the wake of the 1935 uprising, communism functioned less as a political reality than as a cultural obsession, a threat capable of unifying disparate sectors of Brazilian society.45 The Cohen Plan provided a tangible “proof” of subversion, collapsing the distance between rumor and evidence. By invoking violent images (churches in flames, massacres of civilians) the Plan mobilized visceral fears that rational critique could scarcely counter.46

Military Guardianship and the Politics of Fear

The role of the military in propagating the Cohen Plan underscores its self-image as guardian of national order. By presenting themselves as defenders against subversion, military leaders legitimated their political intervention.47 This self-conception became embedded in Brazil’s political culture, resurfacing in the military coup of 1964, where once again a “communist menace” was invoked to rationalize authoritarian takeover.48 The Cohen Plan thus marks a foundational moment in the construction of a political mythology that equated military rule with national salvation.

The Press and Elite Complicity

The success of the forgery also depended on civilian institutions. Brazil’s major newspapers reproduced the Plan without serious verification, and legislators in Congress endorsed measures grounded in a document many suspected was dubious.49 Such complicity illustrates the dynamics of authoritarian legitimation: the lie worked not only because it was told, but because elites chose to believe it, finding in the fiction a convenient justification for curbing democratic competition.50

Legacies and Lessons

The legacy of the Cohen Plan extended far beyond 1937. Its narrative established a precedent for future deployments of the “red scare,” shaping political rhetoric in Brazil throughout the twentieth century.51 Even when later unmasked as a forgery, the Plan continued to function symbolically, reinforcing narratives of national vulnerability and the legitimacy of authoritarian guardianship. For scholars of comparative authoritarianism, the Cohen Plan illustrates how fragile institutions can be undone not by brute force alone, but by the strategic manipulation of fear.52

Conclusion

The Cohen Plan stands as a striking illustration of how fragile democratic institutions can be subverted by the deliberate manufacture of fear. Far from being an incidental forgery, it was strategically mobilized by Vargas and his allies to construct legitimacy for authoritarian rule. The Plan functioned simultaneously as a text, a myth, and a political weapon: a text authored by an integralist officer, a myth broadcast by the press and the state, and a weapon wielded to dismantle constitutional government.

By examining its origins, dissemination, reception, and eventual exposure, we see that the Cohen Plan’s power resided less in its credibility than in its utility. It confirmed what many Brazilians already feared in the aftermath of the 1935 uprising, and it allowed the Armed Forces and Vargas to position themselves as guardians against chaos. In this sense, the forgery reveals the symbiotic relationship between propaganda, institutional weakness, and elite complicity in authoritarian transitions.

The post-1945 revelations underscore the durability of political lies. Even when discredited, the Cohen Plan remained embedded in Brazil’s political memory, shaping the discourse of military guardianship that resurfaced in 1964 and beyond.53 Comparative analysis shows that Brazil’s experience was not unique: across the interwar world, manufactured crises provided fertile ground for the consolidation of authoritarian regimes.54

Ultimately, the Cohen Plan is not merely a cautionary tale about Vargas’s Estado Novo. It is a broader lesson about the dangers of weaponized disinformation, the complicity of institutions in legitimating falsehoods, and the enduring impact of manufactured threats on political culture. As long as democratic societies remain vulnerable to fabricated crises, the warning of the Cohen Plan retains its urgent relevance.55

Appendix

Footnotes

- Robert M. Levine, Father of the Poor? Vargas and His Era (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 78–80.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil: A Political Biography (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967), 175–78.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo: O fascismo brasileiro na década de 30 (São Paulo: Difel, 1974), 253–57.

- Thomas E. Skidmore, Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964: An Experiment in Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 18–22.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil: A Political Biography (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967), 44–47.

- Robert M. Levine, Father of the Poor? Vargas and His Era (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 65–67.

- Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 123–26.

- Eliana Dutra, “A Intentona Comunista de 1935 e o imaginário político do período Vargas,” in Brasil Republicano: O tempo do nacional-estatismo, ed. Jorge Ferreira and Lucilia Delgado (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2003), 203–24.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 70–72.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo: O fascismo brasileiro na década de 30 (São Paulo: Difel, 1974), 132–38.

- Ricardo Benzaquen de Araújo, Totalidade e contradição: O integralismo de Plínio Salgado (Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1988), 58–64.

- Moacir Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen e Estado Novo (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1967), 41–44.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo, 253.

- Olímpio Mourão Filho, Memórias: A verdade de um revolucionário (Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1978), 87–90.

- Moacir Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen e Estado Novo (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1967), 55–57.

- Robert M. Levine, Father of the Poor?, 79.

- Jeffrey Lesser, Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 121–24.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 176–77.

- Thomas E. Skidmore, Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964, 34–35.

- Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 60–62.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 80.

- Eliana Dutra, “A Intentona Comunista,” 219.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 81.

- Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 63–65.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 178.

- Thomas E. Skidmore, Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964, 36.

- Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 69–71.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 82.

- Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 180.

- Skidmore, Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964, 38.

- Francisco Campos, A Constituição de 10 de novembro (Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1938), 15–17.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo, 301.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 85.

- Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 183.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 90.

- Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 190.

- Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 192.

- Olímpio Mourão Filho, Memórias, 87–90.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo, 255.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 92.

- Moacir Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 112–14.

- Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 9–12.

- Eliana Dutra, “A Intentona Comunista,” 220–21.

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003), 65–68.

- Eliana Dutra, “A Intentona Comunista,” 219–20.

- Robert M. Levine, Father of the Poor?, 80.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 176–77.

- Thomas E. Skidmore, The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964–1985 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 23–25.

- Moacir Werneck de Castro, Plano Cohen, 63–65.

- Hélgio Trindade, Integralismo, 301.

- Jeffrey Lesser, Welcoming the Undesirables, 121–24.

- Levine, Father of the Poor?, 92.

- John W. F. Dulles, Vargas of Brazil, 192–94.

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, 65–68.

- Robert M. Levine, Father of the Poor?, 95.

Bibliography

- Araújo, Ricardo Benzaquen de. Totalidade e contradição: O integralismo de Plínio Salgado. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1988.

- Campos, Francisco. A Constituição de 10 de novembro. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1938.

- Castro, Moacir Werneck de. Plano Cohen e Estado Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1967.

- Dulles, John W. F. Vargas of Brazil: A Political Biography. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967.

- Dutra, Eliana. “A Intentona Comunista de 1935 e o imaginário político do período Vargas.” In Brasil Republicano: O tempo do nacional-estatismo, edited by Jorge Ferreira and Lucilia Delgado, 203–24. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2003.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- Levine, Robert M. Father of the Poor? Vargas and His Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Lesser, Jeffrey. Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Mourão Filho, Olímpio. Memórias: A verdade de um revolucionário. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1978.

- Skidmore, Thomas E. Politics in Brazil, 1930–1964: An Experiment in Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- ———. The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964–1985. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Trindade, Hélgio. Integralismo: O fascismo brasileiro na década de 30. São Paulo: Difel, 1974.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.