He entered office promising to restore the voice of the people, and in many respects he succeeded. But the result was an America more democratic in form but more autocratic in practice.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction — The Jacksonian Revolution in Governance

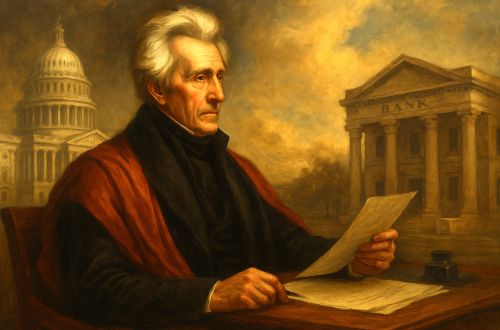

When Andrew Jackson entered the presidency in 1829, he did not merely assume office; he declared a revolution in the American conception of governance. To his supporters, he was the living embodiment of democratic renewal, the self-made man who would purge corruption, break aristocratic monopolies, and restore power to “the people.” To his opponents, he was an autocrat cloaked in popular rhetoric, a man who believed the presidency alone was the true voice of the republic.1 Jackson’s years in office, spanning 1829 to 1837, would become a crucible in which the balance between democracy and executive authority was tested, reshaped, and ultimately redefined.

This was not a period of cautious administration but one of deliberate confrontation. The early republic’s founders had imagined a delicate balance of separated powers: Congress would legislate, the judiciary would interpret, and the executive would execute. Jackson rejected that equilibrium. As he wrote in his 1832 veto of the Bank recharter bill, “The President is the direct representative of the American people.”2 That statement was more than political flourish; it was a doctrinal claim. In Jackson’s view, the executive could claim a popular mandate equal to, and perhaps superior to, that of Congress. The implications of that view would reverberate far beyond his own presidency.

Jackson’s crusade against the Second Bank of the United States became the defining battleground of this new ideology. He saw the Bank as a symbol of elite dominance and constitutional corruption, while its defenders, including Nicholas Biddle and Henry Clay, saw it as essential to national stability.3 When Congress refused to dismantle the institution, Jackson simply removed federal deposits by executive order, firing Treasury Secretary William J. Duane for refusing to comply and replacing him with Roger B. Taney, who would execute his will.4 In doing so, Jackson set a precedent for unilateral executive action in fiscal affairs, one that, in spirit if not in form, anticipated the modern “imperial presidency.”

Yet Jackson’s revolution was not confined to finance. He restructured the very machinery of government through the so-called “spoils system,” replacing hundreds of officials with loyalists under the banner of “rotation in office.”5 He relied increasingly on informal advisers, the “Kitchen Cabinet,” rather than the Senate-confirmed officials prescribed by law, effectively blurring lines between public authority and personal counsel.6 Through these innovations, Jackson concentrated power in the presidency to a degree no predecessor had attempted. What began as a democratic revolt against entrenched privilege evolved into a centralization of authority under a single elected will.

The paradox of Jacksonian democracy, then, lies in its dual legacy: it expanded political participation while eroding institutional restraint. His administration redefined both the scope of presidential power and the nature of democratic legitimacy in the United States. This essay examines how Jackson’s battles (particularly his destruction of the Second Bank, his use of the spoils system, and his reliance on informal executive networks) transformed the presidency into an engine of populist authority. In doing so, it situates Jackson not merely as a figure of his age but as the progenitor of a distinctly American form of democratic autocracy.

The Bank War: Jackson versus the Second Bank of the United States

Few episodes in early American history reveal more about the struggle between democracy and power than Andrew Jackson’s war against the Second Bank of the United States. The Bank had been established in 1816 as a response to the financial chaos following the War of 1812, designed to stabilize currency and regulate credit across the expanding republic.7 By the time Jackson took office, its president, Nicholas Biddle, had turned it into one of the most powerful economic institutions in the Western world. To Jackson and his allies, this made it not a triumph of financial order but a citadel of privilege, a monopoly that placed the lifeblood of the economy in private hands beyond democratic reach.8

Jackson’s opposition was not a matter of economics alone but of political philosophy. In his view, the Bank was an unconstitutional concentration of power favoring the wealthy few at the expense of the many.9 He rejected the Supreme Court’s ruling in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), which had upheld the Bank’s constitutionality, arguing instead that each branch of government was entitled to interpret the Constitution for itself. “The opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges,” he declared in his 1832 veto message.10 That assertion effectively recast constitutional interpretation as a function of the executive will, a radical departure from the precedent of judicial supremacy.

The confrontation reached its climax during the 1832 presidential election. When Biddle and his allies in Congress, led by Henry Clay, sought an early recharter of the Bank, Jackson seized the moment. He vetoed the recharter bill on July 10, 1832, denouncing the institution as “dangerous to the liberties of the people.”11 The veto message became a manifesto of economic democracy, written in language that appealed to farmers, mechanics, and laborers rather than financiers or legislators. It was also a direct challenge to the constitutional balance envisioned by the framers, asserting that the president could defend the people’s interests even against the legislative majority.

Jackson’s victory in the election of 1832 gave him what he interpreted as a popular mandate to destroy the Bank outright. When Congress refused to remove federal deposits, Jackson simply acted on his own authority. He ordered Treasury Secretary William J. Duane to transfer government funds to selected state banks, but Duane refused, citing lack of legal justification. Jackson promptly dismissed him and appointed Roger B. Taney, who complied.12 The move was, in effect, a unilateral executive seizure of fiscal control, bypassing Congress and weaponizing the Treasury as an arm of presidential policy. Historians have rightly seen this as one of the most consequential assertions of executive power in American history.13

The results were immediate and chaotic. The withdrawal of deposits weakened the Bank’s lending capacity, forcing Biddle to contract credit in retaliation, precipitating a wave of economic instability.14 Jackson’s supporters framed the ensuing turbulence as the necessary birth pains of liberty; his opponents called it reckless despotism. Whig newspapers labeled him “King Andrew the First,” depicting him crowned and robed, trampling the Constitution beneath his feet.15 The image captured both his defiance and his paradox: a president who claimed to speak for the people while ruling as if endowed with singular authority.

In destroying the Bank, Jackson did more than eliminate an institution, he redrew the boundaries of executive power. His actions established that the president could not only veto legislation but also unilaterally shape national economic policy. This was not simply populism; it was a structural transformation of governance. The “Bank War” thus became both a victory for democratic rhetoric and a defeat for the constitutional balance of powers. The republic had entered a new era, one in which executive conviction could override institutional restraint, setting a precedent that future presidents would alternately invoke and fear.

Pet Banks and the “Experiment” in Decentralized Finance

After crippling the Second Bank of the United States, Jackson turned to what he called an “experiment” in democratic banking. Federal deposits were to be redistributed among selected state institutions, derisively nicknamed “pet banks,” that would, in theory, bring financial control closer to the people.16 In practice, this decentralization extended Jackson’s political patronage into the economic sphere, intertwining ideology with personal loyalty. The system was not the triumph of fiscal republicanism he envisioned but the creation of a new and unregulated financial order responsive largely to political connections.

Roger B. Taney, newly installed as Treasury Secretary, oversaw the transfer of deposits in 1833.17 His selection of state banks often mirrored the political geography of Jackson’s coalition: Democratic-controlled states received disproportionate allocations, while banks managed by political allies gained privileged access to federal funds.18 This process blurred the line between public stewardship and partisan reward, and it also undercut the constitutional principle that Congress, not the president, held the power of the purse. Jackson justified his actions as protecting the people’s money from an unaccountable monopoly. To his critics, it was nothing short of executive usurpation.

The results were economically destabilizing. Freed from the central regulation once provided by the national bank, the pet banks expanded lending at a reckless pace. Paper currency flooded circulation, credit ballooned, and speculation, particularly in western land, accelerated.19 The speculative frenzy reached dangerous proportions by the mid-1830s, prompting Jackson to issue the Specie Circular in 1836, which required payment for public lands in gold or silver.20 Intended to curb inflation and speculation, it instead triggered a sudden contraction of credit as specie reserves drained eastward, destabilizing banks that had issued notes far in excess of their holdings.

Historians continue to debate whether Jackson understood the scale of the financial chaos he unleashed. Charles Sellers argues that the “experiment” was a logical extension of Jackson’s populist vision, a moral war against the commodification of democracy.21 Daniel Walker Howe, by contrast, views it as an act of ideological blindness: a case where hostility toward financial elites obscured the necessity of sound fiscal management.22 Whatever his motive, Jackson’s measures inadvertently contributed to the Panic of 1837, one of the worst economic crises in the early republic.23 His successor, Martin Van Buren, inherited both the political and financial fallout, spending his presidency defending the “Independent Treasury” system devised to prevent another such disaster.

By replacing institutional stability with political loyalty, Jackson redefined economic governance as an extension of executive conviction. He did not merely dismantle a bank, he dismantled the idea of independent financial administration. The “experiment” in decentralized finance, therefore, was as much a constitutional innovation as an economic one. It transferred fiscal responsibility from institutions to individuals, from law to personality. The enduring paradox of Jacksonian democracy is found here: the claim to empower the people achieved through a deepening dependence on presidential will.

The Spoils System and the Restructuring of the Executive Branch

If the Bank War revealed Jackson’s capacity to wield executive power against entrenched financial interests, the spoils system demonstrated his determination to remake the machinery of government itself. “To the victor belong the spoils,” declared Senator William L. Marcy in 1832, capturing the spirit of an administration that treated officeholding as an extension of democratic turnover.24 Jackson’s defenders hailed the policy as a triumph of equality—no longer would public posts be monopolized by a bureaucratic elite insulated from the people’s will. His critics, however, saw in it the erosion of merit and the rise of a partisan machine that placed loyalty above competence.25

Jackson’s justification for “rotation in office” rested on a populist argument. Long tenure in government, he insisted, bred corruption and distance from the electorate.26 In his first annual message to Congress, he argued that “the duties of public officers are so plain and simple that men of intelligence may readily qualify themselves for their performance.”27 It was a radical claim, reducing the art of administration to moral virtue rather than technical skill. Hundreds of civil servants were dismissed during his first year alone, many replaced with ardent Jacksonians who owed their careers to political allegiance.28

This restructuring extended beyond the replacement of personnel; it altered the very ethos of governance. Carl Russell Fish, in his landmark study The Civil Service and the Patronage, observed that Jackson’s spoils system transformed public service from a career into a reward.29 Under the guise of democratizing opportunity, it entrenched a culture of dependence on the presidency for advancement and survival. While previous presidents had removed some appointees for cause, Jackson institutionalized the practice as policy.30 The government thus became a living embodiment of his political will, a tool for consolidating party unity and enforcing ideological conformity.

The long-term consequences were profound. The federal bureaucracy, once modest and relatively autonomous, became increasingly politicized.31 The system fostered inefficiency, favoritism, and corruption, culminating in the scandals of later decades that spurred the civil service reform movement of the 1870s and 1880s.32 Yet it also contributed to the rise of organized party structures that could mobilize mass participation. By binding local patronage networks to national politics, Jackson helped create the first truly modern American political machine.33 The irony is unmistakable: in seeking to democratize officeholding, he laid the foundation for one of the most hierarchical and disciplined party systems in the republic’s history.

Jackson’s reconfiguration of the executive branch was not an aberration but a deliberate extension of his broader philosophy of governance. He saw the presidency as the only institution directly representing the people, and he shaped the bureaucracy to reflect that principle.34 By subordinating administrative independence to political loyalty, Jackson forged a government both more responsive and more coercive, a democratic monarchy built on popular consent. The spoils system, like his attack on the Bank, embodied the paradox of Jacksonian democracy: equality through control, participation through obedience, and reform through centralization.

The Kitchen Cabinet and the Reimagining of Executive Counsel

Jackson’s consolidation of authority was not confined to the formal instruments of office. In parallel with his purge of bureaucratic independence, he cultivated an informal network of advisers, the so-called “Kitchen Cabinet.”35 This group, composed of loyal journalists, political organizers, and confidants, became the president’s true inner circle, functioning outside constitutional channels and beyond congressional oversight. To his critics, it was an invisible government; to Jackson, it was the only counsel he could trust.

The origins of the Kitchen Cabinet lay in Jackson’s deep distrust of Washington’s political elite. His official cabinet had been riven by scandal, most notoriously the Eaton affair, in which the social ostracism of Secretary of War John Eaton’s wife, Margaret, fractured relations among cabinet members and their spouses.36 Rather than repair the breach, Jackson disbanded much of his official cabinet and turned to a circle of personal advisers: Amos Kendall, his ghostwriter and publicist; Francis Preston Blair, editor of the Washington Globe; Martin Van Buren, his closest political strategist; and Postmaster General William T. Barry, who became a conduit between patronage and policy.37 In doing so, Jackson effectively fused political communication, press management, and executive deliberation into a single network loyal to him alone.

The constitutional implications were profound. The Cabinet had never been formally defined in law, but it had functioned since Washington’s presidency as a deliberative body uniting departmental expertise with presidential oversight. Jackson’s informal advisers, unconfirmed by the Senate and unbound by statute, replaced bureaucratic accountability with personal intimacy.38 As one historian observed, “They were not a shadow cabinet, they were the real one.”39 The president’s critics in Congress accused him of subverting republican norms and creating an “executive junto.” The charge was not misplaced: Jackson’s decision-making process increasingly bypassed institutional consultation in favor of private correspondence and trusted intermediaries.

Amos Kendall’s influence was particularly notable. A gifted propagandist, Kendall shaped Jackson’s public image as the champion of the common man, drafting speeches and messages that recast executive defiance as democratic virtue.40 Blair’s Washington Globe served as the administration’s mouthpiece, attacking opponents and promoting Jacksonian policies in tones that blurred journalism and governance.41 By making the Postmaster General, a position responsible for one of the nation’s largest patronage networks, a member of his inner circle, Jackson further politicized communication itself.42 In this structure, control of information became a tool of executive consolidation.

Historians continue to debate whether the Kitchen Cabinet represented corruption or innovation. Charles Sellers interprets it as a natural extension of Jackson’s populism, a mechanism to bypass elites and speak directly to the people’s representatives through trusted allies.43 Daniel Walker Howe, however, argues that it marked a dangerous personalization of power, replacing institutional deliberation with private persuasion.44 Both views capture part of the truth. The Kitchen Cabinet embodied Jackson’s conviction that legitimacy flowed not from bureaucracy but from loyalty to the popular will as he defined it. It was the human counterpart to his economic and bureaucratic reforms: a government remade in the image of a single man’s trust.

In reshaping the presidency’s inner architecture, Jackson introduced a form of governance that would become a permanent feature of American political life. Every subsequent president, from Lincoln to Roosevelt to Kennedy, maintained informal advisers who exercised influence behind the scenes. The modern White House staff, unelected and largely unaccountable, can trace its lineage to Jackson’s Kitchen Cabinet. What began as an improvised circle of friends evolved into a central institution of presidential power, a living legacy of the Jacksonian conviction that the president alone embodies the will of the nation.

Constitutional and Ideological Implications

Andrew Jackson’s presidency forced the young republic to confront an enduring question: how much power could a democratic executive legitimately wield in the name of the people? His conflicts with Congress and the judiciary revealed not simply a man at war with institutions, but a new theory of constitutional authority. Jackson believed that the president, as the only nationally elected officer, embodied the collective will of the citizenry.45 From this belief flowed an unprecedented expansion of executive initiative—an assertion that the moral legitimacy of democratic leadership could override the procedural restraints of the Constitution.

This philosophy manifested most clearly in his famous statement that “the President is independent of both the legislature and the judiciary.”46 Jackson rejected the idea that any branch of government possessed interpretive supremacy. When Chief Justice John Marshall upheld Cherokee sovereignty in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Jackson allegedly replied, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.”47 Though the remark’s authenticity remains debated, the sentiment reflects his conviction that executive discretion could determine the limits of judicial power. His administration’s subsequent defiance of the Court’s ruling, allowing Georgia to continue violating Cherokee treaties, illustrated the practical consequences of this doctrine.48

In his veto of the Bank recharter bill, Jackson explicitly redefined constitutional interpretation as an active executive duty. “Each public officer who takes an oath to support the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by others,” he declared.49 In that single sentence, he departed from both Jeffersonian restraint and Madisonian balance, asserting an interpretive equality among the branches that, in practice, elevated the presidency as the final arbiter. The veto, once a limited tool of constitutional objection, became under Jackson a political instrument, a means to assert policy dominance.50

This reconceptualization of executive power unsettled contemporaries who saw it as a betrayal of republican principles. Henry Clay condemned Jackson’s approach as “monarchical,” warning that “the veto was converted into a crown prerogative.”51 Daniel Webster likewise denounced the president’s claim to embody the people’s will as a distortion of representative government.52 Yet Jackson’s defenders countered that the framers had intended a strong executive to check legislative corruption and preserve the unity of the nation. They invoked The Federalist Papers, especially No. 70, in which Alexander Hamilton argued that “energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.”53 Jackson, they insisted, had merely revived that principle in a more democratic age.

Historians have long noted that Jackson’s conception of executive authority foreshadowed the modern presidency.54 His willingness to act independently of Congress anticipated Lincoln’s wartime assertions of necessity and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s claim to a “stewardship” model of leadership.55 Yet there is a crucial difference. Lincoln and Roosevelt justified their actions in crises threatening the survival of the Union or the economy; Jackson invoked no emergency greater than the enduring will of the people as he perceived it. The constitutional legacy of that claim is ambiguous: it affirmed democratic responsiveness but eroded the architecture designed to contain it.

Jackson’s presidency thus inaugurated a constitutional paradox at the heart of American democracy. By asserting that popular sovereignty could be exercised most effectively through a single executive, he transformed the presidency from a coequal branch into the moral center of national power. The republic would never return to its earlier equilibrium. Every subsequent debate over executive overreach, from Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus to the modern proliferation of executive orders, echoes the Jacksonian premise that the will of the people can justify nearly any act performed in its name.

Conclusion — Democracy’s Paradox: Popular Rule through Personal Power

Andrew Jackson’s presidency stands as both triumph and warning in the history of American democracy. He entered office promising to restore the voice of the people, and in many respects he succeeded. He expanded suffrage among white men, mobilized unprecedented voter participation, and gave political legitimacy to those previously excluded from the republic’s governing circles.56 Yet the cost of this democratization was the concentration of authority in a single executive whose claim to embody the people’s will placed him above the institutions meant to restrain him. Jackson’s America was more democratic in form but more autocratic in practice.

The transformation he wrought was structural as much as ideological. The destruction of the Second Bank shattered the fragile equilibrium between public and private power, inaugurating a cycle of boom and panic that exposed the volatility of a decentralized financial order.57 The spoils system infused political loyalty into every corner of administration, eroding the notion of a neutral civil service.58 The Kitchen Cabinet blurred the line between public office and private counsel, elevating personal loyalty over legal accountability. And through it all, Jackson’s constitutional theory of executive independence legitimized a presidency that could act as both tribune and tyrant, claiming to defend liberty while consolidating control.

Yet Jackson’s paradox cannot be dismissed as hypocrisy alone. His democratic populism was rooted in genuine moral conviction. He believed that government must reflect the sentiments of ordinary citizens rather than the calculations of elites.59 His conception of the presidency as the “direct representative of the people” expressed a deep, if dangerous, faith in popular sovereignty. The danger lay not in his intent but in his precedent: by equating the will of the people with the will of the president, he blurred the boundary between democracy and authority. Every future expansion of executive power—from Lincoln’s wartime actions to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal—would echo the Jacksonian claim to moral mandate.60

Historians have long wrestled with this dual legacy. Robert Remini, Jackson’s principal biographer, viewed him as a heroic democrat who “infused vitality into the Constitution.”61 Charles Sellers and Daniel Walker Howe, by contrast, saw in him the origins of a populist authoritarianism that sacrificed institutional balance for political passion.62 Both are correct. Jackson’s presidency was not a deviation from the American experiment but an evolution of it, a test of whether democracy could survive its own enthusiasms.

In the end, Jackson’s impact was not confined to his era. His redefinition of the executive branch altered the trajectory of the republic. He demonstrated that in a democracy, the greatest threat to liberty may not come from kings or oligarchs, but from the people’s own chosen champion. His legacy endures in every modern debate over executive authority, every struggle between populism and constitutionalism, every moment when power claims to speak for the people. Jackson left behind a republic forever changed, one more democratic in voice, more fragile in structure, and forever haunted by the paradox he embodied: the pursuit of freedom through the power of one man.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 335–37.

- Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States,” July 10, 1832, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 5:437.

- Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 361–64.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Bank War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967), 142–47.

- Carl Russell Fish, The Civil Service and the Patronage (New York: Longmans, Green, 1905), 66–70.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 294–98.

- Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 293–97.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 374–77.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 342–44.

- Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States,” July 10, 1832, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 5:437–39.

- Ibid., 5:440.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Bank War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967), 142–48.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 292–94.

- Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York: W. W. Norton, 1969), 73–75.

- “King Andrew the First,” political cartoon, 1832, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Bank War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967), 181–84.

- Ibid., 185.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 347–49.

- Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 400–03.

- Andrew Jackson, “Specie Circular,” July 11, 1836, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 6:504–05.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 303–06.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 381–84.

- Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York: W. W. Norton, 1969), 97–100.

- William L. Marcy, speech in the U.S. Senate, January 1832, Register of Debates in Congress, 22nd Cong., 1st sess., 1326.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 385–87.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 353–55.

- Andrew Jackson, “First Annual Message,” December 8, 1829, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 4:120–21.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 45–48.

- Carl Russell Fish, The Civil Service and the Patronage (New York: Longmans, Green, 1905), 70–74.

- Ibid., 75–76.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 308–10.

- Paul P. Van Riper, History of the United States Civil Service (Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, 1958), 18–20.

- Michael F. Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 61–64.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 356–57.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 359–61.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 389–90.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 50–53.

- Ibid, 52.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and His Times (New York: Penguin, 1999), 248.

- Amos Kendall to Andrew Jackson, September 10, 1834, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 5:577–78.

- Donald B. Cole, Jacksonian Democracy in New Hampshire (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1970), 112–15.

- William T. Barry, “Annual Report of the Postmaster General,” December 1834, U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 23rd Cong., 2nd sess.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 312–14.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 391–93.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 363–65.

- Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States,” July 10, 1832, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 5:437.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars (New York: Viking, 2001), 257–58.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 401–03.

- Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank,” 5:439.

- Charles M. Wiltse, “The Development of the American Veto Power,” American Historical Review 30, no. 2 (1925): 284–86.

- Henry Clay, speech in the U.S. Senate, July 10, 1832, Register of Debates in Congress, 22nd Cong., 1st sess., 1344.

- Daniel Webster, “Speech on the Veto Message,” July 11, 1832, in The Papers of Daniel Webster: Speeches and Formal Writings, ed. Charles M. Wiltse (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1986), 2:45–48.

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 70, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), 423.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 320–22.

- Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents (New York: Free Press, 1990), 13–14.

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 366–68.

- Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York: W. W. Norton, 1969), 115–17.

- Carl Russell Fish, The Civil Service and the Patronage (New York: Longmans, Green, 1905), 78–80.

- Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States,” July 10, 1832, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 5:437–40.

- Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents (New York: Free Press, 1990), 14–16.

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 63.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 320–22; Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 401–03.

Bibliography

- Barry, William T. “Annual Report of the Postmaster General.” December 1834. U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 23rd Cong., 2nd sess.

- Clay, Henry. Speech in the U.S. Senate, July 10, 1832. Register of Debates in Congress, 22nd Cong., 1st sess.

- Cole, Donald B. Jacksonian Democracy in New Hampshire. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Fish, Carl Russell. The Civil Service and the Patronage. New York: Longmans, Green, 1905.

- Hamilton, Alexander. The Federalist No. 70. In The Federalist Papers, edited by Clinton Rossiter, 421–26. New York: Signet Classics, 2003.

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Jackson, Andrew. “First Annual Message.” December 8, 1829. In The Papers of Andrew Jackson, edited by Harold D. Moser, vol. 4. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

- ———. “Specie Circular.” July 11, 1836. In The Papers of Andrew Jackson, edited by Harold D. Moser, vol. 6. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

- ———. “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States.” July 10, 1832. In The Papers of Andrew Jackson, edited by Harold D. Moser, vol. 5. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

- Kendall, Amos. Letter to Andrew Jackson, September 10, 1834. In The Papers of Andrew Jackson, edited by Harold D. Moser, vol. 5. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

- Marcy, William L. Speech in the U.S. Senate, January 1832. Register of Debates in Congress, 22nd Cong., 1st sess.

- Neustadt, Richard E. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. New York: Free Press, 1990.

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars. New York: Viking, 2001.

- ———. Andrew Jackson and the Bank War. New York: W. W. Norton, 1967.

- ———. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

- ———. Andrew Jackson and His Times. New York: Penguin, 1999.

- Sellers, Charles. The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Temin, Peter. The Jacksonian Economy. New York: W. W. Norton, 1969.

- Van Riper, Paul P. History of the United States Civil Service. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, 1958.

- Webster, Daniel. “Speech on the Veto Message.” July 11, 1832. In The Papers of Daniel Webster: Speeches and Formal Writings, edited by Charles M. Wiltse, vol. 2. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1986.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- “King Andrew the First.” Political cartoon, 1832. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.13.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.