Ultimately, the history of the kangaroo court is not simply about the failure of law on the frontier. It is about the fragility of law everywhere.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Jumping Justice: Frontier Law and the Birth of a Metaphor

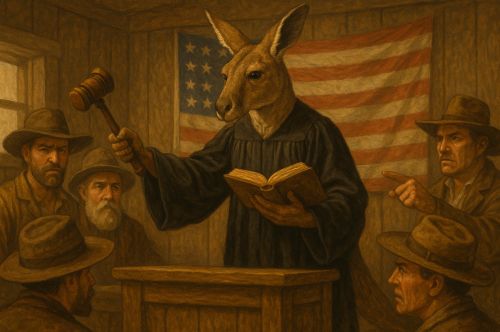

The expression kangaroo court has long served as shorthand for any tribunal in which verdicts precede evidence and authority outweighs law. It conjures the image of proceedings more theatrical than judicial, a performance of justice in which the outcome is never in doubt. Yet the term itself is distinctly American in origin, emerging during the turbulent era of expansion and self-governance on the nineteenth-century frontier. To trace its evolution is to examine the uneasy balance between order and liberty in a society that prized both individual initiative and communal control.

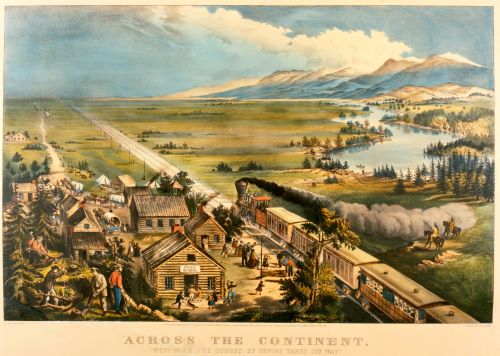

The first documented use of the phrase dates to 1841 in the United States, appearing in print just as the nation’s western boundaries began to surge toward California.1 Within a decade, it was being widely applied in the mining camps of the Gold Rush, where thousands of prospectors arrived in lawless territories lacking any formal judicial infrastructure.2 These communities, improvising their own systems of arbitration, created “miners’ courts” to settle disputes ranging from theft to claim-jumping. Such courts could operate efficiently and even fairly, but they also lent themselves to partiality and abuse.3 It is in this volatile environment (part legal necessity, part social experiment) that the term kangaroo court gained traction.

One enduring theory suggests that the expression derived from the itinerant “jumping judges” who “hopped” from camp to camp dispensing summary justice.4 These ad hoc tribunals, often convened in tents or saloons, offered verdicts that reflected more the temper of the crowd than the rule of law. Their proceedings, hurried and uneven, mirrored the metaphorical leap implied by the kangaroo itself: a jump over reason, due process, or fairness toward a predetermined end. The phrase’s migration from literal description to moral critique demonstrates how frontier culture, in its improvisation of authority, gave American English a durable symbol of judicial mockery.

This essay investigates that symbolic birth. By tracing the social and linguistic origins of kangaroo court, it argues that the phrase encapsulates not only the peculiarities of frontier justice but also a deeper national anxiety about legitimacy and power. What began as a local colloquialism for makeshift tribunals evolved into a moral indictment of corrupted institutions. To study the kangaroo court, then, is to study the American experiment in law itself; its improvisations, its failures, and its enduring metaphors of justice betrayed.

Etymology, Early Attestations, and Theoretical Origins

The origin of kangaroo court has long provoked curiosity among historians of language and law alike. Its earliest attested use appeared in an 1841 Daily Picayune article describing an improvised judicial proceeding during a social gathering.5 The phrase, even then, carried a tone of ridicule. Its pairing of the exotic animal with the solemnity of the courtroom created a comic dissonance, mocking the arbitrariness of proceedings that lacked genuine legal foundation. The timing of the phrase’s appearance, just before the migration westward intensified, suggests that it reflected a growing skepticism toward informal justice systems sprouting in newly settled territories.

As the Gold Rush of 1849 drew thousands into California’s mining camps, the term gained a distinct cultural footing. In these rough frontier settlements, miners often lacked access to established courts and instead organized “miners’ tribunals” or “miners’ meetings” to settle disputes.6 According to historian Duane Smith, these institutions combined aspects of Anglo-American common law and communal decision-making but often blurred the line between legal order and mob rule.7 It was within such spaces that the kangaroo court became a living metaphor, a description of those tribunals that appeared legitimate in form but arbitrary in practice.

The theory that the phrase arose from the so-called “jumping judges” remains both compelling and contested. These traveling magistrates, who “hopped” from one mining settlement to another, embodied the volatility of frontier justice: swift, portable, and often self-serving.8 Their rulings, though pragmatic, frequently reflected personal alliances or financial interests rather than legal principle. Linguistically, the image of the “kangaroo” captures the sense of motion, leap, and imbalance that characterized these proceedings. Yet as linguist Michael Quinion observes, the metaphor may also derive from the idea of overlooking evidence or logic, “jumping to conclusions” and rendering verdicts that bypassed reason altogether.9

Alternative explanations add further layers to the term’s etymology. Some have proposed that “kangaroo” was chosen simply as a symbol of foreignness and absurdity, reflecting the American fascination with Australian fauna in the mid-nineteenth century.10 The animal’s pouch, meanwhile, offered another metaphorical resonance: the notion that proceedings were “in the pouch,” or predetermined before they began.11

These competing theories, while unprovable, reveal the richness of the linguistic imagination through which Americans interpreted their evolving legal realities. The term’s precise origin may never be known, but its persistence suggests that it captured something essential about the tension between order and opportunism in a self-made republic.

Institutional and Social Context: Frontier Legal Order and Informal Justice

The nineteenth-century American frontier was a space where law existed more as aspiration than infrastructure. In the absence of established courts or reliable officers, settlers devised their own systems of governance, improvising justice as they built communities. What emerged was a patchwork of local norms that combined the memory of common law with the urgency of survival.12 These ad hoc arrangements were not always illegitimate. They often represented the only possible means of adjudicating conflict where the nearest territorial judge might be hundreds of miles away. Yet necessity easily shaded into arbitrariness. The line between self-governance and vigilantism was as thin as a tent flap in a mining camp.

California’s early mining settlements provide a particularly vivid illustration of this tension. When gold was discovered in 1848, the population of the Sierra foothills exploded, drawing miners from the eastern United States, Latin America, Europe, and China.13 Amid this rush, questions of ownership and theft proliferated faster than any territorial authority could manage. In the absence of official law, miners developed their own codes (some written, others purely customary) establishing “miners’ courts” to resolve disputes.14 These assemblies resembled town meetings more than formal courts. The presiding officer was often chosen by acclamation, and jurors were selected from among the disputants’ peers. Verdicts were delivered publicly and immediately enforced by community consensus.

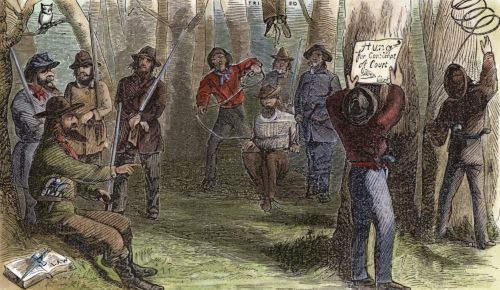

At their best, such courts embodied a rough republicanism: justice by the people for the people. At their worst, they devolved into kangaroo courts, where influence, prejudice, or anger outweighed evidence. As historian Roger McGrath notes, miners’ justice could be “swift and certain but not always impartial,” often reflecting the moral codes of transient men far removed from established society.15 Punishments ranged from fines and expulsions to whippings or hangings, depending on the camp’s temperament.16 The arbitrariness of these outcomes (legal one day, violent the next) illustrates the fragility of institutional legitimacy in a frontier context.

The phenomenon of “claim-jumping” amplified this fragility. When one miner abandoned a site temporarily, another might seize it, invoking ambiguous local rules to justify the act.17 Miners’ courts convened rapidly to settle such disputes, and because the economic stakes were immediate, decisions were often hasty. The combination of urgency, profit, and personal alliances created fertile ground for injustice. Here the term kangaroo court resonated not merely as mockery but as social diagnosis: justice leaping too quickly to judgment.

These informal institutions also reveal a paradox at the heart of American expansion. The very settlers who distrusted distant authority created their own local despotisms when necessity demanded it. The improvisational justice of the mining camps was, in one sense, democracy in its rawest form; in another, it was despotism by majority will.18 Such contradictions illuminate why the kangaroo court metaphor endured. It was not simply a linguistic curiosity but a moral commentary on a nation inventing its own law in the wilderness and discovering how fragile law can be when power and consensus replace principle.

Mechanisms, Features, and Critiques of Frontier Kangaroo (or Pseudo-) Courts

The essence of the kangaroo court lay not merely in its outcomes but in its procedures. Its defining feature was speed. Frontier communities often prided themselves on efficiency, seeing delay as weakness. In an environment where fortune could vanish overnight, justice too had to be immediate.19 Trials could begin within hours of an accusation, and verdicts were often delivered before sunset. This rapidity was not always malicious as miners and settlers were motivated by the need to maintain order, but it carried the inherent risk that process would be sacrificed to convenience. The absence of appeal or oversight turned expedience into potential abuse.

Most kangaroo-style tribunals followed a recognizable pattern. A gathering of townsmen, frequently armed, would form a “jury” and appoint a respected miner or prospector as “judge.”20 Witnesses were called, but cross-examination was rare. In many cases, the accused was allowed to speak only briefly before the crowd reached a decision.21 Verdicts were determined not by established evidence but by reputation and rumor. A man known for drunkenness or deceit could be convicted as easily for character as for crime. This reflected a frontier moralism that conflated social conformity with legal guilt. The result was a system less judicial than performative, in which the appearance of justice mattered more than its substance.

Punishment in these tribunals carried a similarly theatrical quality. Public humiliation was common: offenders might be paraded through camp, tarred, feathered, or made to stand on a barrel while the community jeered.22 The spectacle reinforced solidarity among participants and affirmed a shared sense of moral order. Yet the boundary between symbolic and lethal punishment was thin. Lynchings were sometimes presented as extensions of miners’ courts, and vigilante committees justified executions as the final stage of community justice.23 Contemporary observers recognized that this blurred line between legality and violence undermined the very civil order the frontier claimed to create.

Criticism of such tribunals emerged even in their own time. Newspaper correspondents traveling through California and Colorado frequently denounced these proceedings as “parodies of law.”24 Judges who wandered from camp to camp earned the derisive nickname “jumping judges,” accused of tailoring verdicts to the whims of the crowd or their own financial advantage.25 The Daily Alta California in 1852 warned that “men who make law as they go, break it as they please,” capturing the volatile balance between authority and anarchy.26 These contemporary critiques give the kangaroo court its enduring resonance as an emblem of corrupted process masked as order.

The performative dimension of frontier justice also fascinated later historians and legal scholars. Lawrence Friedman observed that such proceedings represented law in its embryonic state, reflecting a society improvising authority without the institutional scaffolding of a state.27 What they created was not absence of law but law without restraint, where community sentiment operated as both legislator and executioner. This blurred distinction between justice and vengeance exposed the fragility of legality in spaces ungoverned by formal power. The kangaroo court became a mirror through which Americans saw the costs of self-rule untempered by institutional accountability.

Beyond the frontier, the metaphor evolved into political critique. By the late nineteenth century, journalists and politicians applied “kangaroo court” to describe any process that feigned impartiality while predetermining results, from partisan congressional hearings to corrupt labor tribunals.28 The term’s elasticity reveals its moral potency: it named a pattern of power cloaked in legality, a phenomenon as relevant in Washington as in a mining town. That transfer from local slang to national idiom underscores how the frontier’s improvisations of justice left a permanent imprint on American political language.

Modern legal theorists have continued to analyze the concept as a warning about process and legitimacy. The kangaroo court functions as a symbol of procedural decay, marking the point at which institutions cease to protect individuals from collective will.29 In this sense, its frontier origins are not anachronistic but exemplary. They dramatize the perennial struggle between order and fairness, between the authority that maintains peace and the justice that preserves liberty. What the mining camps enacted in miniature, later societies would repeat on larger stages: the temptation to trade due process for control. The kangaroo still leaps, not through the deserts of California, but through every system where judgment arrives before evidence.

Transmission, Metaphor, and Subsequent Uses

As the nineteenth century waned, kangaroo court escaped the frontier and entered the national lexicon. By the 1860s the phrase appeared in newspapers far removed from mining camps, applied to political meetings, party caucuses, and labor disputes.30 The metaphor had detached from its literal context to signify any proceeding that mimicked legality while concealing bias. This linguistic migration paralleled the nation’s own transformation: the rough camps of the Sierra Nevada had given way to the industrial cities of the Gilded Age, yet the suspicion that power could masquerade as justice remained. In this sense, the phrase became a populist weapon, a way for ordinary Americans to denounce institutions they perceived as corrupt or predetermined.31

The turn of the twentieth century deepened this association. During the labor upheavals of the 1910s and 1920s, striking workers invoked kangaroo court to describe company-sponsored tribunals designed to punish organizers.32 Journalists used the term to criticize military hearings during World War I and Prohibition-era trials marked by haste and prejudice.33 Each use re-energized the metaphor’s moral charge, reaffirming that due process was inseparable from democracy itself. In popular culture, novels and stage plays adopted the expression to depict injustice in miniature, a single phrase capable of conjuring the farce of authority unrestrained.

By the mid-twentieth century, the term had assumed global resonance. The Nuremberg defendants complained of a “kangaroo court,” as did critics of Cold War show trials and political purges.34 American commentators deployed it against McCarthy-era hearings, civil-rights prosecutions in the South, and later, military tribunals at Guantánamo Bay.35 Its rhetorical power lay in universality: a kangaroo court was not tied to geography but to the moral anatomy of injustice. Wherever verdicts preceded evidence, the metaphor leapt naturally to mind.

Contemporary scholars view the persistence of the phrase as a linguistic inheritance of the frontier’s improvisational law. Legal historian Robert A. Ferguson observed that American rhetoric continually returns to theatrical images of judgment, a courtroom as stage, justice as performance.36 The kangaroo court endures because it names that uneasy drama: the spectacle of law stripped of legitimacy yet still clothed in its forms. From California’s mining camps to modern political trials, the phrase has remained a cultural shorthand for the betrayal of process. Its endurance confirms the lasting lesson of the frontier, that when law moves faster than conscience, justice travels by leaps and bounds.

Conclusion

The kangaroo court began as a joke of the frontier, a phrase whispered with wry humor among men who knew that justice on the edge of civilization was often a matter of chance. Yet its survival across nearly two centuries reveals something deeper than frontier wit. What started as a mocking label for miners’ tribunals evolved into a cultural metaphor for injustice itself. The frontier’s improvisations of law, born from necessity, became a mirror reflecting the American struggle to reconcile liberty with order. The term’s endurance in political and legal discourse marks it as a moral warning encoded in language, a reminder that law’s form without its fairness is merely theater.37

The mechanisms of those early tribunals exposed a paradox that continues to haunt democratic societies. Communities that distrusted central authority devised their own systems of governance, but in doing so, often reproduced the very coercion they feared. The miners’ meetings and “jumping judges” of California embodied the creative self-rule of the republic, yet also its capacity for exclusion and cruelty.38 To call a proceeding a kangaroo court is, therefore, to indict not only corruption but hypocrisy: the betrayal of freedom’s own rhetoric. Law on the frontier was never simply lawless; it was a contest over who possessed the right to define justice.

Across time, the metaphor’s leap from frontier slang to global political idiom underscores its adaptability. From nineteenth-century mining camps to twentieth-century show trials and twenty-first-century military tribunals, the kangaroo court has denounced every institution that hides arbitrariness beneath the robes of order.39 Its persistence testifies to the moral continuity between past and present, the recognition that process is not mere procedure, but civilization’s conscience. When that conscience falters, injustice proceeds with all the vigor of the animal that gave the metaphor its name.

Ultimately, the history of the kangaroo court is not simply about the failure of law on the frontier. It is about the fragility of law everywhere. The same instinct that led miners to improvise courts in the wilderness endures whenever societies, faced with crisis or fear, sacrifice deliberation for control. The frontier has long since vanished, but the danger it revealed remains: that justice, once unmoored from fairness, will always find a way to leap ahead of truth.40

Appendix

Footnotes

- “Kangaroo Court,” Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Donald J. Pisani, To Reclaim a Divided West: Water, Law, and Public Policy, 1848–1902 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), 47–48.

- Duane A. Smith, Rocky Mountain Mining Camps: The Urban Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967), 112–15.

- William Safire, “On Language: Kangaroo Court,” The New York Times Magazine, March 19, 1989.

- “Kangaroo Court,” Lexington Intelligencer (Lexington, MO), June 1841, cited in Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Donald J. Pisani, To Reclaim a Divided West: Water, Law, and Public Policy, 1848–1902 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), 47–48.

- Duane A. Smith, Rocky Mountain Mining Camps: The Urban Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967), 112–15.

- William Safire, “On Language: Kangaroo Court,” The New York Times Magazine, March 19, 1989.

- Michael Quinion, “Kangaroo Court,” World Wide Words, July 4, 2009, https://www.worldwidewords.org/qa-kan1.html.

- Bruce Moore, Speaking Our Language: The Story of Australian English (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 143.

- The Law Dictionary, “Three Features of a Kangaroo Court,” accessed October 2025, https://thelawdictionary.org/article/three-features-kangaroo-court/.

- Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 3rd ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 322–24.

- Malcolm J. Rohrbough, Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 87–90.

- Donald J. Pisani, To Reclaim a Divided West: Water, Law, and Public Policy, 1848–1902 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), 47–48.

- Roger D. McGrath, Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 29.

- Duane A. Smith, Rocky Mountain Mining Camps: The Urban Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967), 113–15.

- Mark Kanazawa, Golden Rules: The Origins of California Water Law in the Gold Rush (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 56–58.

- Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 82–83.

- Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 3rd ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 325.

- Duane A. Smith, Rocky Mountain Mining Camps: The Urban Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967), 113–14.

- Roger D. McGrath, Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 32–33.

- Richard Maxwell Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 88–89.

- John Boessenecker, Gold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999), 141–42.

- Sacramento Daily Union, July 16, 1851.

- William Safire, “Essay; Kangaroo Courts,” The New York Times Magazine, November 26, 2021.

- Daily Alta California, August 12, 1852.

- Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 3rd ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 326.

- Michael Quinion, “Kangaroo Court,” World Wide Words, July 4, 2009, https://www.worldwidewords.org/qa-kan1.html.

- Richard H. Fallon Jr., “Judicial Supremacy, Departmentalism, and the Rule of Law in a Populist Age,” Texas Law Review 3, no. 96 (2018): 487-553.

- Lexington Intelligencer (Lexington, MO), June 1841, cited in Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 704.

- Philip Taft, The A.F. of L. in the Time of Gompers (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1970), 214.

- Christopher Waldrep, Roots of Disorder: Race and Criminal Justice in the American South, 1817–80 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 189.

- Rebecca West, A Train of Powder: Six Reports on the Nuremberg Trials and Others (New York: Viking, 1955), 62.

- Neal K. Katyal, “Equality in the War on Terror,” Stanford Law Review 59 (2007): 1365-1394.

- Robert A. Ferguson, The Trial in American Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 7–8.

- Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 3rd ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 326.

- Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 83.

- Robert A. Ferguson, The Trial in American Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 8.

- Richard H. Fallon Jr., “Judicial Legitimacy and the Rule of Law,” Harvard Law Review 118, no. 6 (2005): 1798.

Bibliography

- Boessenecker, John. Gold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

- Brown, Richard Maxwell. Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Daily Alta California. August 12, 1852.

- Ferguson, Robert A. The Trial in American Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Fallon, Richard H., Jr. “Judicial Supremacy, Departmentalism, and the Rule of Law in a Populist Age.” Texas Law Review 3, no. 96:487 (2018): 487-553.

- Friedman, Lawrence M. A History of American Law. 3rd ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Katyal, Neal K. “Equality in the War on Terror.” Stanford Law Review 59 (2007): 1365-1394.

- Kanazawa, Mark. Golden Rules: The Origins of California Water Law in the Gold Rush. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York: W. W. Norton, 1987.

- McGrath, Roger D. Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Moore, Bruce. Speaking Our Language: The Story of Australian English. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Pisani, Donald J. To Reclaim a Divided West: Water, Law, and Public Policy, 1848–1902. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

- Quinion, Michael. “Kangaroo Court.” World Wide Words. July 4, 2009. https://www.worldwidewords.org/qa-kan1.html.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Safire, William. “Essay; Kangaroo Courts.” The New York Times, November 26, 2021.

- Sacramento Daily Union. July 16, 1851.

- Smith, Duane A. Rocky Mountain Mining Camps: The Urban Frontier. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967.

- Taft, Philip. The A.F. of L. in the Time of Gompers. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1970.

- The Law Dictionary. “Three Features of a Kangaroo Court.” Accessed October 2025. https://thelawdictionary.org/article/three-features-kangaroo-court/.

- West, Rebecca. A Train of Powder: Six Reports on the Nuremberg Trials and Others. New York: Viking, 1955.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.