To study the French Revolution, then, is to confront the fragility of all revolutions. Every movement for emancipation risks becoming its own oppressor, every call for unity risks silencing dissent.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The French Revolution stands as both a monument and a warning in the annals of modern history. What began in 1789 as a cry for liberty, equality, and fraternity soon became one of the most convulsive experiments in human self-government ever attempted. Inspired by Enlightenment reason and sharpened by economic despair, the revolutionaries of France sought to dismantle the ancien régime and reconstruct society upon rational and moral foundations. In doing so, they imagined not merely a change of government but the rebirth of humanity itself, a civic regeneration of the human spirit through law, virtue, and reason. Yet, the same forces that gave the Revolution its moral grandeur would also become the instruments of its destruction. The pursuit of virtue hardened into fanaticism, and the language of liberty transformed into the rhetoric of suspicion and fear.

At its inception, the Revolution was marked by a rare alignment between intellectual idealism and popular will. The Third Estate, long denied political voice, rose against privilege and hierarchy, its deputies proclaiming themselves the National Assembly and asserting sovereignty in the name of the people. In the streets of Paris, the storming of the Bastille symbolized the death of royal despotism and the birth of civic agency. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen declared that all men were born free and equal in rights, a radical departure from centuries of absolutism and divine monarchy. Yet beneath these triumphs lay an unacknowledged contradiction: the Revolution’s moral absolutism demanded not only freedom but purity, not only equality but unanimity. Dissent could not be tolerated in a movement that defined itself as the voice of the nation’s virtue.

As crises deepened (foreign war, internal revolt, and economic collapse) the Revolution devoured its own children. The rhetoric of salvation justified the logic of terror. Robespierre’s Committee of Public Safety, believing it spoke for the general will, made violence the instrument of virtue. Tens of thousands perished under the guillotine, victims of a government that claimed to act in their name. In the name of liberty, the Revolution created a machinery of repression more total than that of the monarchy it had destroyed. When Robespierre himself fell to the same blade that had silenced so many others, the Revolution’s moral core collapsed, leaving only exhaustion, cynicism, and the longing for order.

From this void emerged the figure who would both consummate and betray the Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte. Promising stability after chaos, he harnessed the Revolution’s reforms to his own authoritarian design. The Republic, born in the name of reason, yielded to the empire of ambition. What began as an assault on tyranny ended in its reinvention, cloaked in the language of revolutionary glory. The French Revolution thus embodies the enduring paradox of modern revolutions: that the pursuit of absolute freedom often ends by enthroning new forms of domination. Its legacy is not only political but moral, reminding us that liberty, untempered by humility, can become indistinguishable from power.1

The Birth of a Revolution: Hope, Unity, and the Fall of the Old Order

The year 1789 opened with a sense of imminent transformation. The summoning of the Estates-General for the first time since 1614 was a recognition that the monarchy itself had lost its moral authority. France’s financial collapse was merely the symptom of a deeper crisis: the inability of absolutism to reconcile privilege with principle. The Third Estate, composed of commoners who represented ninety-eight percent of the population, arrived not merely to advise the king, but to redefine the nation. When its deputies declared themselves the National Assembly, they acted on the revolutionary premise that sovereignty belonged not to the monarch but to the people.2 The act was quiet, almost procedural, yet it marked the beginning of a political philosophy that would soon shake the world.

The unity that followed was electric and, for a time, genuine. Clergy and nobles defected to the National Assembly, signaling a brief moment when reform seemed capable of transcending class and interest. In Paris, the storming of the Bastille on July 14 became the visual grammar of revolution, a single day that condensed centuries of resentment into a tangible victory.3 The fall of that fortress-prison was more symbolic than strategic (it held few prisoners) but its stones carried the weight of feudalism’s demise. The nation was no longer a hierarchy but a people in motion.

In August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen codified the Revolution’s creed: that men are born and remain free and equal in rights.4 Drafted in part by the Marquis de Lafayette with the counsel of Thomas Jefferson, it fused French rationalism with American republicanism, transforming abstract philosophy into political scripture. For a brief season, it seemed that the human race itself might begin anew. The monarchy, though still standing, was already hollow. Louis XVI accepted the declaration under duress, his authority eroded by both the people’s suspicion and his own indecision. The Revolution appeared to have triumphed without tyranny, to have reimagined the state through reason rather than violence.

Yet unity was never as solid as it appeared. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, passed in 1790, split the nation’s conscience in two. By subordinating the Church to the state, the revolutionaries ignited a moral conflict that pitted religious devotion against civic loyalty.5 Rural uprisings and peasant resistance revealed that the Revolution’s universal language could not erase local identities. At the same time, the economic crisis deepened; inflation and food shortages turned the crowd, once the Revolution’s heart, into its unpredictable conscience. The popular will, once celebrated as sacred, began to frighten its own creators.

By 1791, the king’s failed flight to Varennes destroyed what remained of trust between crown and people. The Revolution, still draped in its idealism, had entered a phase of existential doubt. It could no longer reconcile liberty with authority, faith with reason, or equality with order. The new world that had begun in the name of humanity was already haunted by the specter of chaos. The Revolution was turned against the very people who started it.6

Radicalization and the Reign of Terror: Virtue as Violence

Revolutions rarely move in straight lines; they spiral, drawn by the centrifugal force of their own ideals. By 1792, the Revolution’s rhetoric of liberty had given way to the language of emergency. War with Austria and Prussia inflamed national paranoia, while rumors of royalist plots and foreign conspiracies convinced many that France was surrounded by enemies both within and without. The September Massacres, in which mobs slaughtered prisoners accused of counterrevolutionary sympathies, signaled that the Revolution’s moral compass had begun to fracture.7 The call for freedom was now indistinguishable from the cry for vengeance.

Maximilien Robespierre emerged as the Revolution’s most enigmatic prophet. A lawyer turned moral crusader, he believed that democracy required not indulgence but virtue and that virtue could not survive without the cleansing power of terror.8 When he declared before the National Convention that “terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible,” he was not abandoning the Revolution’s ideals but radicalizing them.9 In Robespierre’s imagination, violence was the instrument by which the Republic purified itself of corruption. The guillotine became both a tool of law and a ritual of faith, an altar upon which the Revolution sacrificed its own children to the god of moral perfection.

The machinery of repression moved with terrifying precision. The Committee of Public Safety, established in April 1793, concentrated executive power in the hands of twelve men who claimed to speak for the general will. Under its authority, revolutionary tribunals condemned thousands as “enemies of liberty.”10 The categories were elastic (nobles, priests, hoarders, political rivals) anyone who questioned the Republic’s purity could be accused of treason. The Girondins, once fellow revolutionaries, were purged and executed. The Hébertists and Dantonists soon followed. By the spring of 1794, the Revolution had turned inward entirely, consuming not monarchists but revolutionaries themselves. The state of virtue had become a state of fear.

Yet Robespierre’s fall in July 1794 revealed that terror had destroyed the very legitimacy it claimed to defend. His speech on The Principles of Political Morality, meant to sanctify the Revolution through civic virtue, had already become a confession of its corruption.11 In the name of moral clarity, he had created moral chaos; in the name of the people, he had alienated them. His execution without trial, cheered by the same crowds who once revered him, marked not the triumph of moderation but the exhaustion of revolution. The ideal of universal liberty lay buried beneath the ruins of its own absolutism.

Historians note that the Terror was not an aberration of the Revolution but its dark fulfillment.12 The dream of regenerating humanity through political will had collapsed into a nightmare of suspicion and slaughter. France, bled of faith in either king or conscience, was ready to accept any authority that promised order. In the vacuum left by virtue, the logic of power began to reassert itself.

The Directory: From Revolutionary Fatigue to Political Decay

The execution of Robespierre in July 1794 did not restore the Revolution’s moral health; it merely shifted the stage upon which corruption would play. The Thermidorian Reaction, named for the month in which the Jacobin leader fell, sought to replace virtue with pragmatism. The new government, led by moderates weary of fanaticism, claimed to end terror and restore stability. But stability without justice proved as hollow as virtue without mercy.13 The Convention dismantled the machinery of repression, yet the moral vacuum left by Robespierre’s fall could not be filled by cynical self-preservation. France had overthrown both monarchy and morality, and what remained was an exhausted republic staggering under the weight of its own contradictions.

The Constitution of 1795, which established the Directory, attempted to create balance through complexity. Five directors shared executive authority, while two legislative councils restrained them. It was an architecture of suspicion, designed to prevent another Robespierre.14 Yet in practice it guaranteed paralysis. The Directory possessed neither the charisma of revolutionary fervor nor the legitimacy of popular faith. Its leaders enriched themselves through speculation and graft, while the people, impoverished by inflation and famine, looked upon the government with contempt. The Revolution had promised equality, but bread was scarcer than ever, and its ideals had become the currency of hypocrisy.

The army, once the defender of the Republic, became its arbiter. To preserve itself from royalists and radicals alike, the Directory relied increasingly on military intervention to suppress uprisings and secure elections.15 Each act of coercion eroded the Republic’s civic foundation. The generals, particularly a brilliant young Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte, emerged as both saviors and threats. His victories in Italy not only filled the Republic’s coffers but captured its imagination.16 In a nation starved for glory, Napoleon’s triumphs seemed to redeem the Revolution’s promise by other means. He was hailed as the incarnation of merit, a man who rose through talent rather than birth. Yet his rise revealed a fatal irony: the Revolution that had destroyed monarchy was preparing to enthrone another kind of sovereign.

Corruption became the Directory’s defining character. Elections were annulled, coups staged, and dissent crushed in the name of preserving the Republic. The ideals of 1789 had become bureaucratic ornaments, invoked but no longer believed. The people, disillusioned and impoverished, ceased to defend a government that no longer spoke in their name.17 The Revolution’s democratic experiment, once blazing with conviction, now flickered dimly, sustained only by inertia and force.

By 1799, the Directory had lost all political oxygen. Economic crisis, foreign wars, and administrative incompetence reduced the government to a fragile alliance of convenience. The Republic was less a state than a holding action, a temporary arrangement until a stronger will could impose coherence.18 That will soon arrived in the figure of Napoleon, who embodied both the Revolution’s energy and its exhaustion. The age of ideals was ending; the age of authority was about to begin.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire: From Republic to Empire

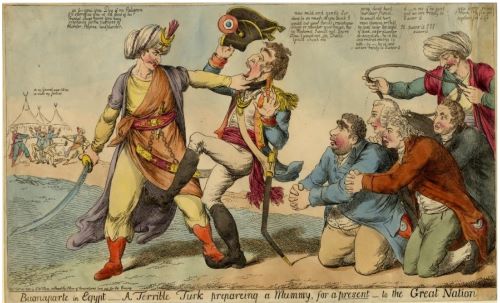

By the autumn of 1799, France was ready to exchange liberty for order. The political experiment that had begun with the promise of universal rights now survived only by military discipline. The people no longer dreamed of equality; they longed for stability. Amid this exhaustion, Napoleon returned from his Egyptian campaign as the embodiment of revolutionary success. His victories, real and imagined, were magnified by propaganda into symbols of destiny.19 The army adored him, the public trusted him, and the politicians feared him. In this imbalance of forces, the Republic ceased to be governed; it was waiting to be taken.

The coup of 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (November 9, 1799), was executed not with the thunder of revolution but with the precision of bureaucracy. Bonaparte and his allies in the legislature dissolved the Directory under the pretense of reform, accusing it of corruption and weakness, charges that were true enough to make the lie believable.20 In two days of political theater and calculated intimidation, the Revolution’s last republican institution was swept away. The Constitution of Year VIII, ratified the following month, established the Consulate and concentrated power in the hands of the First Consul, Napoleon himself.21 The Revolution’s circle had closed: one man now held authority in the name of the people, as the king once had in the name of God.

What distinguished Napoleon from the monarchs of old was not the scope of his power but the skill with which he clothed it in revolutionary language. The Consulate claimed to preserve liberty by enforcing efficiency, to protect equality through hierarchy, and to realize the Revolution’s ideals by abandoning their substance.22 Napoleon reformed the administration, codified the Code Civil, and reconciled with the Catholic Church, all in the name of national unity. Yet each measure that appeared to stabilize France also centralized control. The Revolution’s moral vocabulary (citizenship, merit, progress) was transposed into the lexicon of empire. In the name of reason, the Republic had become a machine for conquest.

Public consent for this transformation was neither coerced nor blind. After a decade of chaos, the French welcomed the order Napoleon promised.23 The ideals of 1789, tarnished by terror and corruption, now seemed impractical luxuries. In Napoleon, the people saw not a tyrant but a redeemer, a man who restored dignity to a nation humiliated by its own revolution. He presented himself as the guardian of the Revolution’s gains: equality before the law, secular education, and the destruction of feudal privilege. Yet beneath this veneer lay a new absolutism, grounded not in divine right but in meritocratic despotism. The Revolution did not die with Napoleon’s rise; it survived in chains, its principles repurposed as instruments of imperial rule.24

The coup of 18 Brumaire thus marked both an end and a beginning. The Revolution’s energy did not vanish, it was harnessed. Its dream of universal liberty was converted into an imperial mission, its faith in the people replaced by faith in one man. By 1804, when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in Notre-Dame, the Revolution had completed its transformation: the republic of citizens had become the empire of glory. The tricolor still flew, but its meaning had changed.

The Revolution’s Dialectic: Liberty Reforged as Power

The French Revolution did not simply collapse; it metamorphosed. What began as an insurrection for human rights and civic virtue evolved, through the alchemy of history, into an empire justified by efficiency and glory. The Revolution’s tragedy lay not in its failure to change France, but in its success at changing it too completely. By dismantling monarchy, Church, and aristocracy, the revolutionaries destroyed the moral and institutional frameworks that had once restrained power.25 In their place arose the conviction that reason and will could remake society from the ground up. It was a faith as absolute as the divine right it replaced. When that faith faltered, only discipline remained, and discipline required a master.

The movement’s internal logic was circular: liberty required virtue, virtue required unity, and unity demanded control. Each turn of the wheel drew the Revolution closer to tyranny. Robespierre’s guillotine and Napoleon’s sword were not opposites but continuations of the same impulse, the belief that the general will could be embodied in a single authority.26 The dream of collective freedom thus ended in personal rule. What had begun as a revolt against absolutism became a study in its reinvention. The Revolution’s dialectic was complete: liberty had been reforged as power.

And yet, the Revolution did not vanish with the Consulate or the Empire. Its language (rights, equality, citizenship) outlived its institutions. Even as Napoleon crowned himself emperor, the Code Civil carried the Revolution’s egalitarian spirit into law. The same ideals that justified terror later justified reform.27 In this paradox lay the Revolution’s enduring legacy: it proved that history’s most transformative ideas often survive their own corruption.

To study the French Revolution, then, is to confront the fragility of all revolutions. Every movement for emancipation risks becoming its own oppressor, every call for unity risks silencing dissent. But without such risks, no moral progress is possible. The Revolution’s blood and betrayal did not extinguish its light; they revealed how blindingly dangerous that light can be when unshaded by humility. In the ruins of the guillotine and beneath the arches of empire, one lesson remained: liberty cannot be imposed; it must be sustained, daily, by restraint as much as by passion.28

Appendix

Footnotes

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 87.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 56–59.

- Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1989), 403–406.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 80.

- Timothy Tackett, Becoming a Revolutionary: The Deputies of the French National Assembly and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Culture (1789–1790) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 214–218.

- Schama, Citizens, 602.

- David Andress, The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 113–116.

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006), 102.

- Maximilien Robespierre, “On the Principles of Political Morality,” speech to the National Convention, February 5, 1794.

- Andress, The Terror, 189–192.

- Robespierre, “On the Principles of Political Morality.”

- Andress, The Terror, 246.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 274–276.

- Isser Woloch, The New Regime: Transformations of the French Civic Order, 1789–1820s (New York: W.W. Norton, 1994), 187–190.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 281.

- Patrice Gueniffey, Bonaparte: 1769–1802 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 112–118.

- Woloch, The New Regime, 202.

- Woloch, The New Regime, 208.

- Patrice Gueniffey, Bonaparte: 1769–1802 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 279–283.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 300–303.

- Woloch, The New Regime, 217–220.

- Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London: Macmillan, 1994), 42–46.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 312.

- Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution, 59.

- Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 318.

- Andress, The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France, 249.

- Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution, 82–86.

- Schama, Citizens, 873.

Bibliography

- Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Gueniffey, Patrice. Bonaparte: 1769–1802. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. London: Macmillan, 1994.

- Robespierre, Maximilien. “On the Principles of Political Morality.” Speech to the National Convention, February 5, 1794.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1989.

- Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006.

- Tackett, Timothy. Becoming a Revolutionary: The Deputies of the French National Assembly and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Culture (1789–1790). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Woloch, Isser. The New Regime: Transformations of the French Civic Order, 1789–1820s. New York: W.W. Norton, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.