Each collapse (whether agrarian, fascist, postcolonial, or digital) produces not only political debris but human remains of conviction. Those who once defined themselves through certainty must now live amid pluralism’s doubt.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Politics of Return

Populism, in all its historical guises, has been a politics of belonging and betrayal. It invites the disaffected to see themselves as the moral center of a nation, wronged by distant elites and corrupted institutions. Yet when such movements collapse (whether by defeat, discredit, or internal decay) their adherents are left marked by the very defiance that once empowered them. Their reintegration into civic life is fraught with suspicion, for they return carrying the moral residue of an ideology that divided the body politic into the righteous and the damned. The paradox is as old as populism itself: movements that proclaim to restore trust in “the people” often leave their followers among the least trusted citizens once the fervor subsides.1

This essay explores that paradox across history, tracing the problem of distrust that shadows populist followers after their movements dissolve. It examines cases from the agrarian populists of the late nineteenth-century United States to the fascist aftermath in postwar Europe, from postcolonial populisms in Latin America and Africa to the new digital populisms of the twenty-first century. Each era reveals the same enduring challenge, how individuals who once embraced exclusionary or conspiratorial narratives are received by societies that later condemn those ideologies. The social penalties for past belief differ by context, yet the structure of distrust remains consistent: former believers are viewed as moral risks, their loyalty to pluralism uncertain, their repentance suspect.2

By approaching populism as a historical cycle rather than a momentary upheaval, what follows situates reintegration as both a political and moral process. Populist movements thrive on simplicity and moral absolutism; liberal societies, by contrast, depend on ambiguity, compromise, and institutional faith. When the former gives way to the latter, distrust becomes a mechanism of protection as much as punishment. To understand how democracies recover from populist convulsions, one must examine not only the fall of charismatic leaders or failed revolts but also the quieter aftermath, the citizens trying to return home from history’s losing side.3

The Nineteenth Century: Agrarian Populism and Democratic Disillusionment

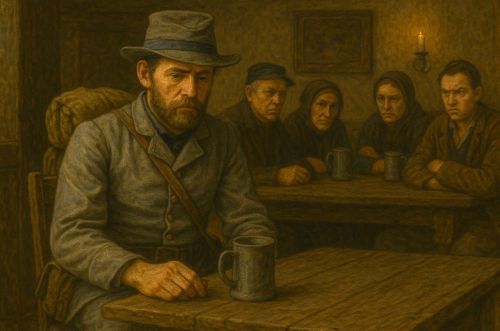

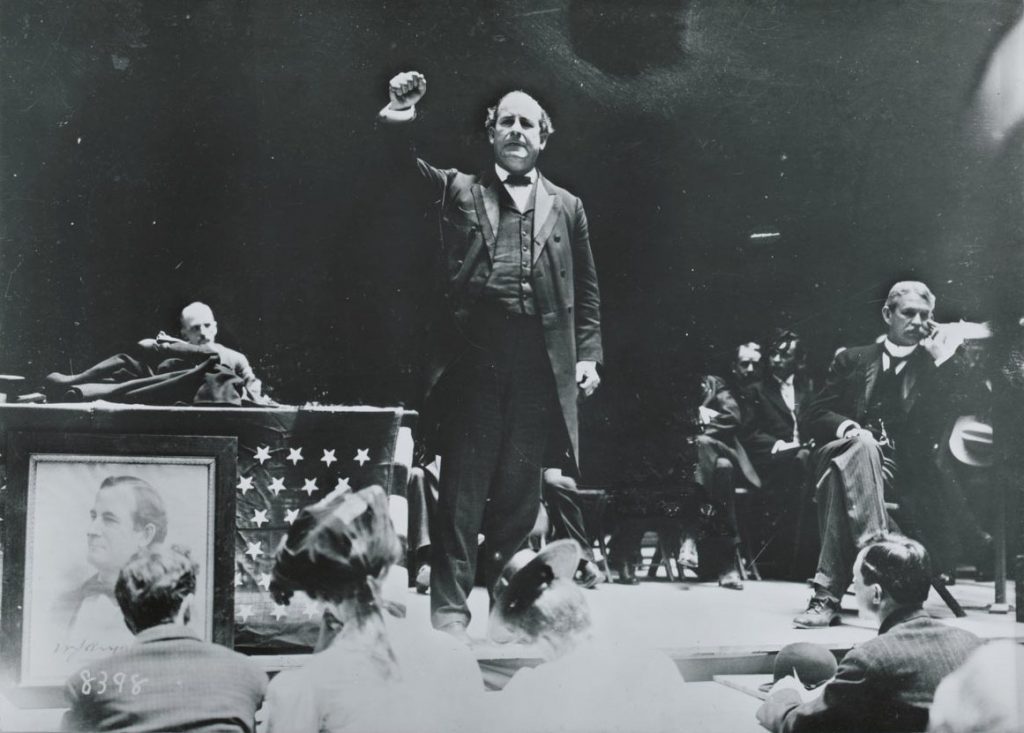

In the late nineteenth century, the United States witnessed the rise of the People’s Party, a populist coalition of farmers and laborers who challenged the industrial and financial elites dominating the Gilded Age economy. They railed against monopolies, railroad trusts, and gold standard policies, framing their struggle as a defense of “the plain people” against entrenched corruption. The movement briefly transformed American political discourse, but its eventual collapse in the 1890s left many of its adherents politically homeless. After fusion with the Democrats in 1896 and William Jennings Bryan’s defeat, the Populists’ rhetoric of moral warfare against elites became a liability. Those once hailed as defenders of democracy were recast as radicals or cranks, unable to reenter a political mainstream they had denounced as illegitimate.4

The experience of these early populists reveals how movements built on anti-institutional rhetoric undermine the trust required for later reintegration. By claiming moral superiority over “corrupt” systems, populists generate an us-versus-them framework that persists even after electoral defeat. When the People’s Party dissolved, many followers tried to return to local politics, journalism, or labor organizing, but they carried the stigma of disloyalty to institutional norms. Their former identity as “the people’s vanguard” became a social mark of alienation.5 In this sense, the Populist collapse offers a microcosm of populism’s historical aftermath: its adherents struggle to regain credibility precisely because their movement’s legitimacy depended on the delegitimization of everyone else.

The populist revolt of the 1890s also demonstrated the emotional power of collective grievance. Agrarian populists were not cynics (they believed in reform, economic fairness, and democratic participation) but their methods eroded the very civic trust they sought to restore.6 When the movement faded, it left behind a moral residue of bitterness, a conviction that truth and justice could not coexist with political compromise. That sense of betrayal (by elites, by parties, and finally by history) would echo in later populist cycles around the world.

Interwar Europe: The Return of the Disenchanted

Nowhere was the problem of reintegration more morally charged than in postwar Europe. The collapse of fascist and ultra-nationalist populisms after 1945 left millions of ordinary citizens implicated, some as active collaborators, others as passive enablers of authoritarian rule. In Italy, followers of Mussolini’s regime faced social ostracism even when they had held only peripheral roles. The Fascist Party’s glorification of national unity had dissolved into defeat and humiliation, and those who once hailed the Duce as savior were recast as moral outcasts.7

In Germany, the process was even more complex. Denazification sought to distinguish ideological conviction from coerced participation, yet for many former party members or sympathizers, reintegration required navigating a society eager to rebuild while reluctant to remember.8 The resulting silence, what historians have termed “the politics of forgetting,” created a fragile form of coexistence rather than genuine reconciliation. Ordinary Germans returning to civic life often carried an unspoken awareness of complicity, while those untouched by the regime’s crimes viewed them with quiet suspicion. Populism’s moral absolutism, once weaponized to define who belonged, now reversed its direction: former believers found themselves excluded from the very national community they claimed to embody.

This postwar distrust was not only punitive but functional. Democracies emerging from authoritarian populism needed to safeguard against its return.9 The vigilance of institutions, the restrictions on former fascist parties, and the cultural stigmatization of overt nationalism all reflected an attempt to rebuild civic trust by controlling its boundaries. Reintegration, therefore, was never merely social; it was political containment under the guise of moral rehabilitation. By mid-century, Europe’s lesson was clear: when populism fuses mass emotion with exclusionary ideology, its ruins are inhabited not only by the defeated but also by the distrusted.

Postcolonial Populism and the Betrayal of Liberation Ideals

In the decades following World War II, populism reemerged in the newly decolonized world as a rhetoric of liberation. Charismatic leaders from Latin America to Africa harnessed populist language to unify fractured nations, promising justice, equality, and renewal. Juan Perón in Argentina, Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, and Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana each framed themselves as tribunes of the people against oligarchic or foreign domination.10 Yet when their regimes faltered (undermined by economic crises, corruption, or authoritarian drift) their followers bore the stigma of misplaced faith. The populist bond that had once symbolized patriotic devotion became, in defeat, a mark of naivety or complicity.

In Argentina, Peronism’s collapse in 1955 left a divided nation struggling to reconcile loyalty with legitimacy. Former Peronists were banned from public office, censored in the press, and branded as enemies of democracy.11 Their attempts to rejoin political life were haunted by accusations of demagoguery, despite the movement’s genuine social reforms. Similarly, in Ghana, Nkrumah’s overthrow in 1966 transformed his supporters from nationalists into political pariahs.12 Populism’s moral intensity, its demand for unconditional allegiance, rendered post-collapse neutrality impossible. Those once celebrated as voices of the people were now viewed as remnants of authoritarian ambition.

These postcolonial experiences exposed the double edge of populist inclusion. By centering legitimacy on emotional identification with a leader, they blurred the line between political participation and personal devotion. Reintegration thus became not only a social challenge but an existential one: former followers had to reconstruct civic identities apart from the moral totalism that once defined them.13 The distrust they encountered was less about past crimes than about the perceived inability to think independently, a legacy of populism’s seduction of certainty. Across continents, the cycle repeated: liberation rhetoric yielded to disillusionment, and the dream of moral unity ended in suspicion.

In several nations, the disillusionment that followed populist collapse produced enduring cultural effects that outlasted the leaders themselves. In Latin America, Peronism’s populist template persisted as a kind of political inheritance, revived, revised, and contested by future generations seeking to claim authenticity in the name of “the people.”14 In parts of Africa, postcolonial populism created a similar shadow: even when regimes changed, public trust in institutions never fully recovered, as citizens continued to equate political charisma with moral legitimacy.15 The very mechanisms that had mobilized collective hope (the language of unity, moral renewal, and redemption) became obstacles to civic reconstruction. Once such moral economies collapse, reintegration demands not only political adjustment but a reconstitution of belief itself. The former follower must learn to think politically rather than devotionally, a transformation that history shows to be among the most difficult of all.

The Contemporary Cycle – Digital Populism and the Politics of Disavowal

In the early twenty-first century, populism entered a new phase shaped by digital connectivity and algorithmic amplification. Leaders such as Donald Trump in the United States, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines mobilized online platforms to create virtual communities of grievance and moral solidarity.16 These digital populisms replicated the emotional structure of earlier movements (charisma, conspiracy, and the exaltation of “the people”) but with a crucial difference: they left behind an enduring, searchable archive of belief. When these movements fractured or lost power, the internet became both witness and warden, preserving the traces of past allegiance long after individuals had renounced them. Reintegration, once a private matter of conscience, now unfolded in public view.

The digital age has thus transformed the sociology of repentance. In earlier populist collapses, former adherents could retreat into silence, rewriting their political past through selective memory. Online, however, their posts, videos, and hashtags remain visible, producing a form of digital stigma that complicates reconciliation.17 Employers, institutions, and even family members can trace ideological histories with a few clicks, converting transient emotion into permanent record. The result is a paradox of modern transparency: while technology promises accountability, it also denies the possibility of forgetting. Former believers may seek reintegration, but the digital archive makes every past enthusiasm a potential act of self-incrimination.

At the collective level, this permanence reshapes how societies distribute distrust. Rather than institutional purges or legal sanctions, twenty-first-century democracies employ social media itself as an informal system of discipline.18 Online exposure replaces formal punishment, producing what scholars describe as “networked shaming.” Those once aligned with populist causes (anti-immigrant movements, anti-vaccine campaigns, or election conspiracies) find themselves ostracized through decentralized enforcement. This differs from the postwar experience in Europe, where reintegration was bureaucratic; today, it is algorithmic. Suspicion is not declared by courts but reinforced by clicks, shares, and memory feeds that continually resurrect the past.

The difficulty of reintegration is heightened by the emotional economy of digital populism. Online movements thrive on outrage, humor, and irony, modes that blur sincerity and performance. When the fervor fades, individuals must not only retract false beliefs but also disentangle their social identities from communities that once gave them validation.19 Many who attempt to leave find themselves isolated: distrusted by mainstream society and alienated from their former networks. Reintegration, therefore, becomes an act of double estrangement, demanding both ideological revision and emotional reconstruction.

Yet the persistence of digital populism reveals a deeper continuity with its historical predecessors. Like the agrarian or postcolonial populists, modern adherents often frame their disillusionment as betrayal rather than transformation.20 They may abandon a leader but retain the moral absolutism that first attracted them. This continuity suggests that distrust toward former populists is not simply punitive; it reflects an awareness of how easily moral certainty can be reborn under new slogans. The challenge for democratic societies lies in distinguishing genuine ideological evolution from opportunistic rebranding.

Ultimately, the digital cycle of populism closes the historical loop. The populist promise of direct connection between leader and people, once mediated by rallies and pamphlets, now finds perfect expression in the immediacy of social media.21 Yet this same immediacy ensures that the collapse of belief is as public as its performance. Those who seek to return to civic normalcy do so under the gaze of an unforgetting archive, navigating a world where forgiveness requires both moral courage and algorithmic mercy. Reintegration, once a matter of private repentance, has become an act of public negotiation, a struggle not only for trust but for narrative control in an age that never forgets.

Patterns of Distrust and Historical Continuity

Across centuries and continents, the aftermath of populism has revealed a persistent rhythm of enthusiasm, collapse, and suspicion. Though each movement arises from distinct historical circumstances (agrarian crisis, fascist ideology, postcolonial nationalism, or digital disinformation) the social consequences for followers share striking similarities. Populism’s emotional intensity leaves behind a residue of moral absolutism that does not dissolve with defeat.22 Those who once believed themselves the conscience of the nation awaken to find that their moral language, once celebrated, has become evidence of fanaticism. Distrust thus functions as a kind of collective immune response, a mechanism by which societies defend themselves from the return of ideological contagion.

The continuity of this distrust reveals that populism’s real legacy is not political but psychological.23 Each movement cultivates habits of suspicion (against elites, institutions, and pluralism itself) that persist even when its formal structures vanish. Former adherents carry these habits into the societies they rejoin, often unconsciously, shaping the discourse of grievance that enables new populisms to emerge. The boundary between victim and perpetrator blurs: those who once distrusted power now become the distrusted. In this sense, history does not simply repeat populism; it recycles its emotional vocabulary under new names and technologies.

Reintegration is therefore not a linear process but a negotiation between memory and identity. Postwar Europe’s attempts at denazification, Latin America’s democratic transitions, and contemporary online “deplatformings” all express the same tension between forgiveness and vigilance.24 Too much leniency risks the normalization of extremism; too much condemnation risks alienating citizens who might otherwise evolve. The problem lies in balancing historical accountability with the human need for belonging. Democracies can punish behavior but cannot legislate redemption, and without avenues for return, disillusioned citizens may retreat into renewed resentment.

A second continuity lies in the relationship between populism and communication. From pamphlets and rallies to radio broadcasts and digital feeds, populist movements have always depended on the immediacy of message and the collapse of mediation.25 When these channels disappear or turn hostile, former believers lose not only their political community but their mode of self-expression. Reintegration thus requires learning to speak differently, to replace absolutes with nuance, slogans with dialogue. This linguistic transformation parallels the moral one: recovering trust demands recovering complexity.

Ultimately, the historical pattern suggests that distrust after populism is both necessary and perilous.26 It protects democratic societies from moral relapse but can also perpetuate cycles of alienation. The true test of civic maturity lies in distinguishing accountability from persecution, skepticism from contempt. History shows that populism’s ruins are filled not only with failed leaders but with ordinary people seeking a path back into the moral community. Their reintegration, whether granted or denied, determines whether democracy becomes a space of learning or merely a revolving door of exclusion.

Conclusion: Memory, Accountability, and the Ethics of Return

History’s populist afterlives reveal a moral landscape littered with unfinished reckonings. Each collapse (whether agrarian, fascist, postcolonial, or digital) produces not only political debris but human remains of conviction. Those who once defined themselves through certainty must now live amid pluralism’s doubt. Reintegration after populism is therefore not merely about reentering society; it is about learning to inhabit complexity without the comfort of moral purity.27 This is why distrust endures: it is the social memory of absolutism, a collective caution against the return of faith without reflection.

The process of rebuilding trust is inseparable from historical consciousness. Societies that remember their populist pasts with honesty, acknowledging both structural injustices and individual complicity, create conditions for reconciliation.28 Denial, by contrast, ensures repetition. The agrarian radicals of the 1890s faded without resolution, the fascist generation buried guilt beneath silence, and the digital populists of today conceal ideological shame beneath irony. In each case, the refusal to confront one’s own participation preserves populism’s emotional architecture even after its political structures collapse.

Accountability, however, cannot rest solely on condemnation. Democratic resilience depends on the possibility of moral recovery.29 Those who once succumbed to populist simplicity can become, if allowed, its most eloquent critics. Yet such transformation demands both personal humility and public generosity. The moral failure of populism is collective; it reflects the seductions of certainty that tempt every age. To exclude its former believers entirely is to deny that potential for renewal.

Forgiveness, though, must not become forgetfulness.30 Historical empathy requires remembering not only victims but perpetrators, not only those misled but those who misled. The ethics of return rests on the ability to welcome repentance without romanticizing it. Populism thrives when societies draw their moral lines too sharply; it returns when they erase them altogether. The challenge, then, is to construct a civic culture that balances memory with mercy, distrust with discernment.

In the end, the fate of democracy depends less on the destruction of populism than on what follows it.31 If distrust hardens into permanent exclusion, it breeds new alienations; if it softens without reflection, it invites repetition. The true victory over populism is neither punishment nor amnesia but the steady work of moral rehabilitation, teaching citizens once drawn to simplicity how to live again with contradiction. Only then can the politics of belonging yield to the ethics of return.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Mary E. Lease, The Problem of Civilization Solved (Chicago: Independence Publishing Co., 1895).

- Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Lawrence Goodwyn, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

- Margaret Canovan, Populism (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981).

- Jan-Werner Müller, What Is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

- Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. (New York: Vintage, 1955), 58–73.

- Charles Postel, “The Populist Vision Revisited,” Reviews in American History 39, no. 1 (2011): 128–134.

- Lawrence Goodwyn, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976).

- Renzo De Felice, The Jews in Fascist Italy: A History (New York: Enigma Books, 2001).

- Emilio Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996).

- Norbert Frei, Adenauer’s Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

- Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 52–78.

- Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2005).

- Daniel James, Resistance and Integration: Peronism and the Argentine Working Class, 1946–1976 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

- Jeffrey S. Ahlman, Kwame Nkrumah: Visions of Liberation (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2021).

- Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Juan Eugenio Corradi, “Argentina and Peronism: Fragments of the Puzzle,” Latin American Perspectives 1, no. 3 (1974): 3-20.

- Jean-François Bayart, The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly (London: Longman, 1989).

- Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- Alice E. Marwick, Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

- Zizi Papacharissi, Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Sheri Berman, “The Causes of Populism in the West,” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (2001): 71-88.

- Katherine J. Cramer, The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

- Manuel Castells, Communication Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Siva Vaidhyanathan, Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Cass R. Sunstein, #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

- Ian Kershaw, The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler’s Germany, 1944–45 (New York: Penguin, 2011).

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003).

- John Keane, The New Despotism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020).

- Karen Stenner, The Authoritarian Dynamic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Bibliography

- Ahlman, Jeffrey S. Kwame Nkrumah: Visions of Liberation. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2021.

- Bayart, Jean-François. The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. London: Longman, 1989.

- Berman, Sheri. “The Causes of Populism in the West.” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (2001): 71-88.

- Canovan, Margaret. Populism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981.

- Castells, Manuel. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Cramer, Katherine J. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- De Felice, Renzo. The Jews in Fascist Italy: A History. New York: Enigma Books, 2001.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- Frei, Norbert. Adenauer’s Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

- Gentile, Emilio. The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

- Goodwyn, Lawrence. Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- ———. The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. New York: Vintage, 1955.

- James, Daniel. Resistance and Integration: Peronism and the Argentine Working Class, 1946–1976. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Keane, John. The New Despotism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Kershaw, Ian. The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler’s Germany, 1944–45. New York: Penguin, 2011.

- Laclau, Ernesto. On Populist Reason. London: Verso, 2005.

- Lease, Mary E. The Problem of Civilization Solved. Chicago: Independence Publishing Co., 1895.

- Margalit, Avishai. The Ethics of Memory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Marwick, Alice E. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Postel, Charles. The Populist Vision. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Stenner, Karen. The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Sunstein, Cass R. #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Taylor, Charles. The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Corradi, Juan Eugenio. “Argentina and Peronism: Fragments of the Puzzle.” Latin American Perspectives 1, no. 3 (1974): 3-20.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.