The American Republic emerged from violence not as an accident but as its creative condition. The Revolution fused moral purpose with physical defiance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Paradox of Freedom and Force

The American Revolution is remembered as the birth of liberty, yet its origins were steeped in violence. Behind the parchment idealism of the Declaration lay streets filled with fire, crowds, and broken glass. In Boston, New York, and Charleston, mobs of artisans, sailors, and laborers struck first, dragging effigies through the mud, burning customs houses, and tarring officials to the jeers of neighbors.1 To later generations, this energy became sanitized as “spirit,” but to those who lived it, it was rebellion in its rawest form: defiance without permission, justice without restraint.

The colonial elite would later give this unrest the shape of a political creed. When the signers of the Declaration pledged “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor,” they were not engaging in poetic theater. They knew that failure meant execution, their estates seized, their names branded with treason.2 That risk, though genuine, was first borne by those below them, the “lower sort” whose disorder made political argument urgent. The Revolution did not emerge from calm deliberation but from the collision between imperial control and local fury, between petitions ignored and authority despised.

This is the central paradox of American freedom. The Republic that would later claim to embody reason and order was born of acts that defied both.3 The idea that liberty and law can coexist began in a moment when law itself was broken in the name of justice. The Revolution, for all its moral ambition, was not a tidy assertion of rights but a social rupture. To understand its legacy is to recognize that the founders’ noblest ideals were carried forward on a tide of violence, the same violence that made the very language of freedom possible.

The “Lower Sort”: Ordinary Rebels and Radical Action

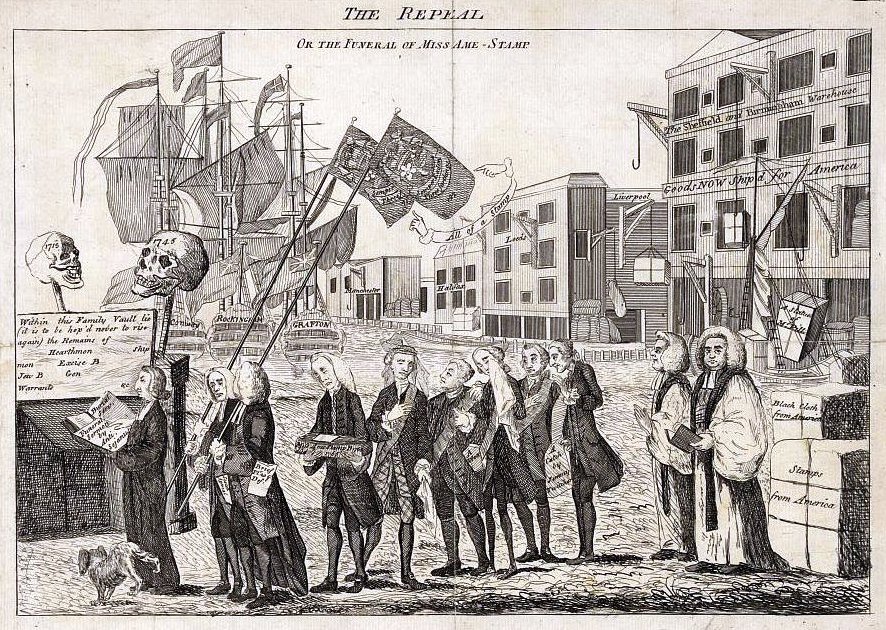

The Revolution’s first blows were not struck by philosophers or statesmen but by men who labored with their hands. Sailors, dockworkers, and apprentices formed the turbulent edge of resistance in the years before 1776. Their grievances were immediate and material, taxes that burdened trade, laws that undercut wages, and the arrogance of officials who enforced them.4 The Stamp Act riots of 1765 and the later attacks on loyalist merchants showed how the politics of liberty took root in the anger of those who had least to lose. To the gentry, these outbursts appeared as chaos; to the “lower sort,” as rebels were referenced by the British, they were assertions of equality before any declaration made it law.

This popular militancy gave physical form to the idea of resistance. Crowds destroyed stamps, raided homes, and forced resignations not through argument but through fear.5 They claimed the streets as their parliament, their actions shaped by a collective understanding that the king’s authority could be contested only through visible defiance. What elite revolutionaries later called “the people” was first a moving, shouting body in motion, one that frightened those who would soon speak in its name. Yet it was this body that made the imperial crisis real. Petitions might have been ignored indefinitely; mobs could not be.

In this tension between radical energy and elite control, the pattern of American revolution was set. Artisans and laborers forced the political question into being, and then men of property translated that disorder into theory.6 Violence became a kind of vocabulary through which political legitimacy was spoken. The destruction of property, so often condemned by those who would later venerate the Revolution, was the very act that brought it into existence. Without the riots that preceded them, the resolutions of Congress might have sounded like rhetoric in a vacuum.

The early patriots understood freedom not as an abstraction but as an act. Their defiance emerged from daily struggle rather than philosophical contemplation.7 They sought redress through disruption because every other form of address had failed. In doing so, they revealed an enduring American truth, that liberty, in its infancy, belonged not to the orderly but to the unruly.

The Elite Conversion: From Disorder to Declaration

For the colonial elite loyalists, and even some sympathetic to the cause, the early riots were alarming spectacles that threatened the very social order they benefited from. Merchants and lawyers watched as their warehouses burned and their neighbors shouted for justice against imperial authority.8 What began as class rebellion soon demanded political explanation, and those explanations became the foundation of revolutionary ideology. Men like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson translated the chaos of the streets into the language of natural rights and civic virtue. In doing so, they re-imagined violence not as anarchy but as a moral necessity, the outward proof of inward conviction.

The transition from mob action to political revolution depended on narrative control.9 The same crowd that once terrified the gentry was recast as “the people,” their fury reinterpreted as patriotism. Elite pamphleteers framed rebellion within the heritage of English liberty, insisting that resistance followed precedent rather than passion. This rhetorical reframing allowed them to legitimize defiance while distancing themselves from its bloodier origins. The language of duty replaced that of vengeance, and the rope that once threatened them was woven into the new banner of independence.

Yet this conversion from disorder to declaration was not simply ideological. It was strategic. By aligning with popular unrest, colonial leaders gained leverage against the Crown and preserved their authority at home.10 They absorbed the energy of the “lower sort” without conceding them real power. In the drafting of declarations and constitutions, the crowd’s voice was muted into representation rather than participation. Violence had done its work; now order reclaimed its place. The republic’s architects could champion rebellion precisely because they had mastered it.

This synthesis of radical action and elite restraint shaped the identity of the new nation.11 The Revolution became both a warning and a model: a story in which violence was righteous when controlled and criminal when not. Through this lens, the Founders sanctified their own defiance while condemning future insurgencies that lacked their approval. The paradox endured. Liberty was born from rebellion, but rebellion itself became suspect once liberty had a government to defend it.

The Paradox of Liberty: Exclusion and the Boundaries of Freedom

Even as the Revolution advanced the rhetoric of universal liberty, its practice remained bound by exclusion. The new Republic that claimed to represent “the people” defined that term narrowly.12 Enslaved Africans, Indigenous nations, women, and the poor stood outside the circle of recognized citizenship. Their labor and suffering had fueled the colonial economy that financed rebellion, yet the promise of freedom did not extend to them. The ideology of equality coexisted with the daily reality of hierarchy. The Revolution thus carried within it a contradiction that would shape American history, liberty proclaimed through the language of rights but guarded by the mechanisms of power.

Enslaved people recognized the meaning of that contradiction early. Many fled to British lines, interpreting the language of independence as hypocrisy.13 For them, the Crown’s offer of emancipation was not treachery but consistency. If liberty was a natural right, it could not belong only to one color or class. Indigenous nations saw the same logic turned against them as “independence” meant renewed invasion. The war that created the United States became, for them, another campaign of dispossession. Revolutionary liberty, celebrated as a human triumph, also functioned as an imperial project in new clothing.

Women likewise found their voices constrained within the rhetoric that had promised renewal.14 They organized for supplies, managed farms and businesses, and sometimes followed armies, yet political representation remained a male prerogative. The very arguments used to justify rebellion, that those who are governed must consent, were denied to half the population. The Revolution’s language inspired them, but its institutions silenced them. The contradiction between principle and practice was not a failure of understanding but a deliberate preservation of order by those who feared its loss.

The paradox of liberty was therefore foundational, not accidental.15 The Revolution’s architects sought to reconcile virtue with power, equality with hierarchy, freedom with control. They succeeded only by compartmentalizing freedom itself, granting it symbolic universality but limited application. The violence that birthed the Republic had momentarily broken social boundaries, yet its leaders swiftly rebuilt them. In the process, the Revolution became a myth of inclusion that rested upon exclusion, a paradox that continues to define the American experiment.

The Legacy of Resistance: Violence as Civic Memory

The Revolution’s inheritance was not simply independence but a moral grammar of resistance that lingered long after the muskets fell silent. The same logic that had justified rebellion against a distant king reappeared whenever Americans faced power they deemed unjust.16 The insurgents of Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts invoked the language of 1776 to defend their right to challenge economic oppression. Though crushed by state militia, their cause reflected the persistence of the revolutionary idea that legitimate authority depends upon justice, not decree. Rebellion, once sacred, was now criminal, yet its spirit endured.

The violence of the founding generation became both example and warning. Each new generation interpreted it differently. Abolitionists in the nineteenth century cited the Revolution as a moral precedent for civil disobedience and, in some cases, insurrection.17 Enslaved people who fled plantations or rose in revolt understood their struggle as the unfinished work of independence. For reformers, 1776 became less a closed event than a perpetual obligation, a reminder that liberty demands renewal through confrontation. Violence was no longer purely physical; it became symbolic, a weapon of words and conscience forged from the Revolution’s memory.

As the Republic matured, that memory was tamed into ritual.18 The fireworks of the Fourth of July replaced the fires of rebellion, and public orations recast insurgents as statesmen. The transformation of revolution into national myth softened its radical edge, allowing citizens to celebrate dissent without practicing it. Yet beneath the pageantry, the legacy of violent resistance persisted as an undercurrent in the American political imagination. From labor strikes to civil rights marches, each new challenge to authority drew upon that buried tradition, the belief that justice may sometimes require disobedience.

This paradoxical legacy shaped the Republic’s moral identity.19 Americans learned to honor their ancestors’ defiance while condemning its recurrence. The violence that had founded the nation became a sacred origin, too dangerous to repeat and too defining to forget. In this unresolved tension lies the enduring character of American freedom: a liberty forever haunted by the force that created it, a conscience divided between reverence for order and reverence for revolt.

Conclusion: The Republic Born in Turmoil

The American Republic emerged from violence not as an accident but as its creative condition. The Revolution fused moral purpose with physical defiance, transforming the destruction of order into the birth of a new one.20 Its leaders learned that liberty could not be secured by appeals to power alone; it had to be taken, defended, and continually justified. The very act of rebellion became the Republic’s founding myth, a reminder that freedom, once wrested from authority, must forever guard against returning to it.

Yet the legacy of that beginning is uneasy. The same violence that freed the colonies also defined the limits of citizenship.21 It made liberty tangible for some while denying it to others, establishing a national pattern in which emancipation and exclusion coexisted. The Founders’ triumph, however noble, left behind a moral inheritance that could not reconcile the rhetoric of equality with the realities of power. The Revolution’s promise was thus perpetual rather than complete, demanding that each generation confront anew the question of who its freedom serves.

The rope that might have hung the “rebels” still shadows the Republic they created.22 It hangs in the imagination as both warning and call, a symbol of the price of dissent and the peril of complacency. The Founders understood that a nation born in rebellion could not survive by obedience alone. To honor their pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” is not merely to revere their courage but to remember its meaning: that liberty, once achieved through struggle, must live through vigilance. The Republic remains what they made it, an unfinished experiment sustained by those still willing to question, to resist, and, when justice demands, to stand defiant.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 45–67.

- Joseph J. Ellis, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (New York: Vintage, 2000), 12.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1993), 104–108.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 183–195.

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 58–74.

- T. H. Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 29–44.

- Woody Holton, Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 102–108.

- Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 118–131.

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967), 103–115.

- T. H. Breen, American Insurgents, 127–134.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 225–232.

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 376–389.

- Sylvia R. Frey, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 21–34.

- Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence (New York: Knopf, 2005), 114–122.

- David Waldstreicher, Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 198–205.

- Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 77–93.

- Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 243–259.

- David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 54–68.

- Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), 66–72.

- Bernard Bailyn, Faces of Revolution: Personalities and Themes in the Struggle for American Independence (New York: Knopf, 1990), 173–185.

- Gary B. Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Viking, 2005), 356–370.

- Edmund S. Morgan, Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), 237–242.

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard. Faces of Revolution: Personalities and Themes in the Struggle for American Independence. New York: Knopf, 1990.

- ———. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence. New York: Knopf, 2005.

- Breen, T. H. American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

- Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. New York: Vintage, 2000.

- Foner, Eric. The Story of American Freedom. New York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

- Frey, Sylvia R. Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Holton, Woody. Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021.

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W. W. Norton, 1975.

- ———. Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

- Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking, 2005.

- ———. The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Richards, Leonard L. Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Sinha, Manisha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

- Waldstreicher, David. In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- ———. Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1993.

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.