James Armistead Lafayette’s life is a testament to how the ideals of the American Revolution were both realized and betrayed in the same moment.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the closing year of the American Revolution, as the armies of George Washington and Charles Cornwallis maneuvered for the fate of an empire, an enslaved man moved quietly between their camps carrying secrets that would decide the war’s end. His name was James Armistead. To the British, he appeared a humble fugitive seeking refuge from his Patriot master; to the Americans, he was one of the most effective double agents in the Revolution’s clandestine struggle. In a conflict fought under banners of liberty while sustained by slavery, his deception embodied both the contradictions and the possibilities of a nation still being imagined.1

Espionage in the eighteenth century was an enterprise of peril and performance. Messages were hidden in buttons, inked in invisible script, or whispered across enemy lines. Yet the intelligence that proved most decisive at Yorktown did not come from coded dispatches or professional spies; it came from an enslaved man whose knowledge of human nature rivaled his skill at deception. Working under the direction of the Marquis de Lafayette, James Armistead infiltrated British headquarters in Virginia by posing as a runaway slave loyal to the Crown. From that position, he ferried information on troop movements, supply routes, and Cornwallis’s defensive plans, intelligence that guided the American and French forces in their final encirclement at Yorktown.2

Armistead’s double life illuminates a seldom-seen dimension of the Revolution: the world of the enslaved who navigated its shifting allegiances not as spectators but as agents. His espionage not only undermined the British campaign but also challenged the Revolution’s moral boundaries, forcing the Patriots’ struggle for independence to confront its own hypocrisy. When peace arrived, it did not bring him freedom. Though Lafayette publicly attested to his indispensable service, Armistead remained enslaved until 1787, when the Virginia Assembly finally granted his petition for emancipation.3

In tracing James Armistead Lafayette’s journey from bondage to battlefield and finally to freedom, this essay explores the intersections of race, loyalty, and intelligence in the Revolutionary era. His story stands as both triumph and indictment, a testament to courage under subjugation and a mirror reflecting the paradox of a republic born proclaiming liberty while denying it to millions. In the quiet cunning of one enslaved man, the Revolution’s contradictions reached their sharpest point and, perhaps, its truest victory.

Background: Enslavement and Early Life

James Armistead was born enslaved in New Kent County, Virginia, sometime around the middle of the eighteenth century, under the ownership of William Armistead, a member of a prosperous family whose plantations and public offices linked them to the colonial elite. His early years unfolded within the strict hierarchies of Virginia’s slaveholding society, where Black labor sustained both the agricultural economy and the social order that defined it.4 Nothing in the legal or moral fabric of that world offered an enslaved person autonomy, yet the upheaval of revolution would momentarily disrupt that order, creating unexpected opportunities for those willing to risk everything to seize them.

By the time the Revolutionary War reached Virginia, the colony’s enslaved population had become both a source of anxiety and strategic potential for all sides. The British had already weaponized the promise of freedom through proclamations such as Lord Dunmore’s in 1775, which offered liberty to enslaved people who fled Patriot masters to fight for the Crown.5 This act not only destabilized the plantation economy but also illuminated the ideological tension of a rebellion waged in the name of liberty while sustaining human bondage. It was within this fractured landscape that James Armistead came of age, a man whose bondage would paradoxically position him to serve the Revolution more effectively than many free men.

The contours of Armistead’s early life remain largely undocumented, as the enslaved left few written records and the law denied them official identities beyond the inventories of property lists. What is certain is that he was intelligent, observant, and trusted enough by his enslaver to petition for permission to assist the Marquis de Lafayette in 1781.6 That consent was crucial. As property, he could not enlist or act on his own behalf. William Armistead’s approval enabled him to enter the service of the Continental Army, though it also underscored the absurdity of his situation, he could fight for a cause defined by freedom only through the sanction of the man who owned him.

Historians have long debated what motivated James Armistead’s decision to volunteer. Some see in his service a calculated pursuit of manumission; others perceive a moral allegiance to the Patriots’ ideals. The surviving evidence suggests a more complex reality: that he, like many enslaved Africans during the war, navigated a world of overlapping dangers and shifting promises.7 Whatever his reasoning, his act of entering the theater of espionage set in motion one of the most consequential intelligence operations in the Revolutionary era.

Entry into Espionage: From Slave to Spy (1781)

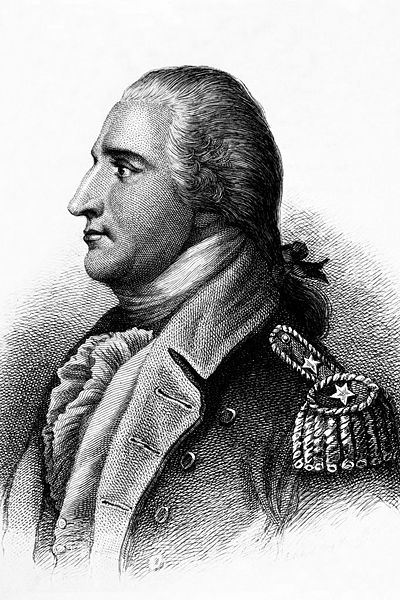

By 1781, the war in Virginia had entered a decisive but chaotic phase. British General Charles Cornwallis had pushed deep into the Tidewater region, while the Marquis de Lafayette maneuvered desperately to contain him. Amid this turmoil, James Armistead stepped into history. With his master’s permission, he entered Lafayette’s service as a volunteer, and at Lafayette’s suggestion, assumed the role of a runaway slave seeking refuge among British forces.8 This deception, carefully constructed, allowed Armistead to exploit the assumptions that sustained slavery itself: that a Black man’s loyalty could only lie with those who promised him freedom.

His infiltration of the British camp began under the command of Benedict Arnold, the notorious defector who was then leading raids through Virginia. Armistead presented himself as a man disillusioned with the Patriot cause and eager to serve the Crown. His performance was convincing. Within weeks, he gained the confidence of Arnold’s officers, gathering details of troop numbers, planned movements, and supply shortages.9 When Arnold departed for New York, Armistead remained behind and soon attached himself to Cornwallis’s headquarters at Yorktown, placing himself at the nerve center of British command in Virginia.

Working under the guise of a servant, Armistead moved freely through encampments and kitchens, listening as officers discussed strategy, logistics, and morale. His intelligence proved invaluable to Lafayette. He regularly traveled between enemy and Patriot lines, delivering reports through intermediaries or in person when suspicion waned. His most significant achievement came when he intercepted false intelligence intended to lure the French fleet away from the Chesapeake. By relaying this deception to Lafayette, Armistead ensured that the French navy remained in position to trap Cornwallis at Yorktown.10

The danger he faced was immense. Espionage was punishable by death, and Armistead’s race offered him no protection from either side. A captured slave-turned-spy could expect execution or reenslavement, not prisoner-of-war status. Yet his double role deepened rather than diminished his effectiveness: his apparent powerlessness rendered him invisible, even as he shaped the war’s outcome. Lafayette later attested that Armistead’s intelligence “contributed principally to the capture of Lord Cornwallis.”11 It was a tribute that history would almost forget, but in 1781, that information helped turn Yorktown from siege to surrender.

By the time Cornwallis laid down his arms in October, the Revolution’s final victory had been decided, and James Armistead’s work was complete. Yet while his reports were instrumental to the triumph of independence, his own freedom remained uncertain, a contradiction that would shadow his postwar life as surely as his courage had defined his wartime one.12

Impact on the Yorktown Campaign and Beyond

The intelligence provided by Armistead in the summer and autumn of 1781 profoundly shaped the allied strategy leading to the Siege of Yorktown. His reports gave Lafayette, and through him General Washington, an intimate understanding of Cornwallis’s troop strength, supply routes, and defensive intentions.13 In an age when communication lagged days behind action, Armistead’s firsthand observations provided real-time awareness of British positions, a decisive advantage that allowed the Franco-American forces to coordinate movements with precision. His dispatches helped confirm that Cornwallis had entrenched himself at Yorktown and intended to await reinforcements by sea, a fatal miscalculation once the French fleet closed the Chesapeake.

Armistead’s intelligence also played a vital role in psychological warfare. Because he moved freely within the British camp, he was able to relay disinformation on Lafayette’s orders, convincing Cornwallis that the Patriot army remained dispersed and ill-prepared for a full-scale assault.14 This false sense of security contributed to Cornwallis’s decision to fortify rather than retreat, sealing his army’s fate. When Washington and Rochambeau converged on Virginia in early September, they found the British cornered, a result of strategic deception that originated in the quiet cunning of an enslaved spy.

In the days leading up to the siege, Armistead continued to supply updates on fortifications and troop morale, his movements coordinated with a growing network of enslaved informants who risked their lives to aid the Patriot cause. These intelligence chains, though rarely documented, reveal the Revolution’s dependence on people who had no legal claim to the liberty they were helping to secure.15 Their efforts not only strengthened the allied campaign but also exposed the profound irony at the heart of the struggle: that freedom for some rested on the bondage of others.

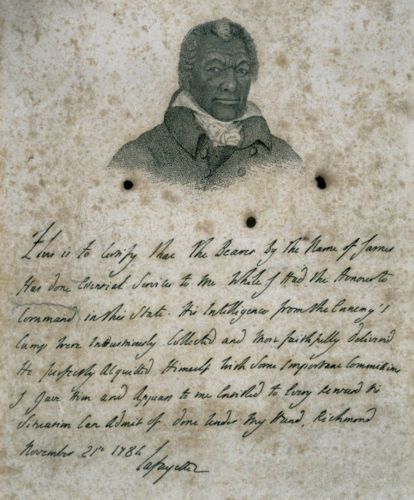

When Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781, the victory was hailed as the culmination of American perseverance and Franco-American cooperation. Yet behind the triumphant cannon fire lay invisible labor, of spies, servants, and enslaved couriers whose names would seldom appear in the histories written afterward. Lafayette understood this and, in the months following the war, wrote a testimonial affirming that James Armistead’s “intelligence from the enemy’s camp was industriously collected and most faithfully delivered.”16 It was a rare acknowledgment of Black agency in a Revolution that so often muted it.

Despite the crucial nature of his service, Armistead returned from war still legally enslaved. While generals exchanged honors and diplomats crafted a peace, he resumed life under the ownership of William Armistead. The liberty he had helped secure for a nation had not yet reached his own doorstep.17 His struggle for freedom, carried out through formal petitions and moral appeals, would become the second and more personal campaign of his life, fought not against an empire but against the inertia of a republic unwilling to extend its ideals to all who had earned them.

Emancipation, Later Life, and Legacy

The triumph at Yorktown closed one chapter of James Armistead’s life and opened another, one defined not by espionage but by the long pursuit of recognition and freedom. Though Lafayette publicly praised his service, Virginia law offered no automatic path to emancipation for enslaved men who had acted as substitutes or spies rather than enlisted soldiers. In 1784, Lafayette personally issued a testimonial affirming Armistead’s “important services rendered to the American cause.”18 Yet despite such powerful endorsement, petitions to the Virginia Assembly initially failed, constrained by statutes that excluded non-combatants from manumission rewards. His continued enslavement laid bare the moral contradiction of a republic celebrating liberty while withholding it from those who had risked everything to secure it.

Undeterred, Armistead petitioned again in 1786, presenting Lafayette’s written testimony and detailed accounts of his espionage under direct orders. This time, the evidence proved irrefutable. In 1787, the Virginia General Assembly passed a special act granting him freedom “for services rendered to the army during the late war.”19 Upon emancipation, he adopted the surname Lafayette in honor of the general who had recognized his valor and advocated on his behalf. The act transformed him from property into citizen, a symbolic restoration of the agency he had already demonstrated years earlier. Yet for all its moral resonance, the gesture was deeply personal: a name taken not from bondage but from friendship.

As a free man, James Armistead Lafayette purchased land in New Kent County and lived out his days as a farmer, husband, and father. He maintained correspondence with Lafayette, who returned to America in 1824 for his celebrated tour. When the two met again at Richmond, the marquis embraced him publicly before an astonished crowd, a reunion that momentarily bridged the racial and social divides of a country still struggling with its founding contradictions.20 Newspapers of the day recorded the meeting with fascination, depicting it as a living tableau of the Revolution’s promise unfulfilled yet enduring.

After his death in 1830, Armistead Lafayette’s story receded into obscurity until historians of the twentieth century resurrected his legacy as one of the Revolution’s most extraordinary figures. Modern scholarship has since placed him at the center of a broader narrative: the participation of enslaved and free Black Americans in the struggle for independence.21 His espionage not only influenced the course of the war but also challenged the moral boundaries of its rhetoric. To remember him is to acknowledge that the Republic’s victory was indebted to those it refused to see.

Interpretation: Freedom, Loyalty, and the Enslaved Spy

The life of James Armistead Lafayette exposes the deep fissures that ran beneath the rhetoric of the American Revolution. While Patriots proclaimed liberty as a natural right, the institution of slavery remained the Revolution’s unspoken contradiction, a foundation of bondage beneath the architecture of freedom. Armistead’s espionage dramatized that tension. His decision to risk death for a cause that denied him personhood is not easily explained through simple notions of patriotism or loyalty.22 Rather, it must be understood as an act of agency within confinement, a strategic assertion of selfhood in a world designed to erase it. His intelligence work for Lafayette was both service and subversion, turning the instruments of oppression into tools of liberation.

Espionage, by its nature, relies on invisibility. Armistead’s success as a spy was made possible precisely because of the assumptions that rendered him unseen. British officers, conditioned to view enslaved people as incapable of political or military significance, never imagined that one might outwit an empire.23 The same social order that denied him literacy or autonomy also blinded his oppressors to his intelligence and courage. In exploiting their prejudice, Armistead inverted the hierarchies of power. His service demonstrated how enslaved individuals could manipulate the very stereotypes used to justify their subjugation.

Yet the moral paradox of his story persists: Armistead’s work advanced a revolution whose victory did not include him. The United States that emerged from Yorktown institutionalized the freedom of its white citizens while codifying the bondage of its Black population for generations to come.24 His eventual emancipation, granted by legislative exception rather than principle, did not undo that contradiction; it illuminated it. Armistead’s life forces historians to confront the uncomfortable truth that the Revolution was simultaneously a war for independence and an engine of exclusion. He stands as a moral witness to the distance between the founding’s language and its practice.

In the historiography of the Revolution, figures like Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson dominate the stage, while men like James Armistead linger in the wings, vital yet marginal, visible only when the curtain of myth is lifted. That erasure is neither accidental nor complete. Recent scholarship has begun to recover the hidden networks of Black intelligence and labor that sustained the Patriot cause, reframing the Revolution as a multiracial struggle rather than a purely white rebellion.25 Within that broader context, Armistead’s contributions represent not anomaly but pattern, one that redefines the Revolution as a site of contested meanings rather than unified ideals.

Ultimately, the story of James Armistead Lafayette is one of reclamation, of his freedom, his name, and his place in the national memory. His life compels Americans to ask what freedom truly meant in a society built upon inequality and to recognize how enslaved people shaped the destiny of a nation that long refused to acknowledge them.26 He was both product and critic of the Revolution that liberated him only belatedly. Through deception, intelligence, and moral endurance, he revealed that the struggle for liberty in America was never complete and never singular; it was, and remains, the unfinished work of all who claim its promise.

Conclusion

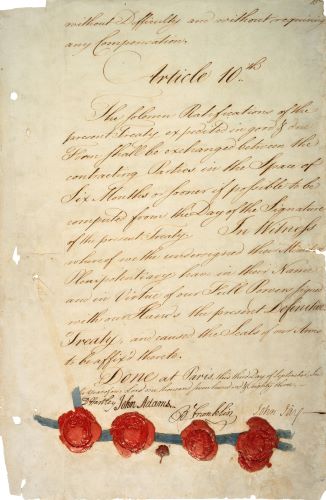

James Armistead Lafayette’s life is a testament to how the ideals of the American Revolution were both realized and betrayed in the same moment. His intelligence work at Yorktown hastened the fall of the British Empire’s most formidable army in North America, securing a victory that transformed the course of world history. Yet when the guns fell silent, the man whose information made triumph possible returned to enslavement.27 His story forces a reckoning with the Revolution’s double legacy, an event that proclaimed liberty while preserving bondage, that birthed a republic of citizens atop a foundation of chattel. In that contradiction, Armistead’s service becomes more than a tale of heroism; it becomes a moral lens through which the Revolution’s promise must be reexamined.

The struggle for recognition that followed his espionage reveals the limits of the new republic’s imagination. Freedom for James Armistead required an act of law, not of conscience, a special legislative exemption rather than a universal principle.28 Yet the very act of petitioning for liberty through the same institutions that had denied it to him showed his unyielding belief in justice’s possibility. In securing emancipation through persistence and proof, he exposed the fragility of a freedom defined only by words. His perseverance stands as a rebuke to the complacency of those who proclaimed independence without understanding its cost.

Over time, memory softened his story into legend, but the substance remained subversive. His reunion with Lafayette in 1824 symbolized more than affection between comrades; it embodied the nation’s unfinished reconciliation with the ideals it claimed to serve.29 In that public embrace, a white French nobleman and a formerly enslaved Black man united before the citizens of a still-divided republic, the contradictions of the Revolution were made visible, if only for a moment, beneath the veneer of patriotic celebration.

Today, James Armistead Lafayette’s name stands where it long should have: among the architects of American victory. His courage reminds us that the Revolution’s truest victories were not only military but moral, won by those who, denied every right, still risked their lives to forge a future beyond subjugation.30 He embodies the paradox of liberty achieved through bondage, and his life compels the ongoing question that outlived his century: how can a nation born from revolution ever rest while some remain unfree?

Appendix

Footnotes

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830),” accessed November 2025.

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette,” accessed November 2025.

- Library of Virginia, “James Armistead Lafayette, Petition for Freedom, 1787,” accessed November 2025.

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830),” accessed November 2025.

- Library of Virginia, “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775,” accessed November 2025.

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette.”

- All Things Liberty, “James Lafayette (James Armistead): An American Spy,” accessed November 2025.

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette.”

- RevWarApps.org, “James Armistead Lafayette, Revolutionary War Pension Application (VAS807),” accessed November 2025.

- History.com, “How a Slave Spy Helped Secure the American Victory at Yorktown,” accessed November 2025.

- Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia, “Lafayette’s Spies,” accessed November 2025.

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).”

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette.”

- Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia, “Lafayette’s Spies.”

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).”

- Library of Virginia, “Testimonial of the Marquis de Lafayette on Behalf of James Armistead,” November 21, 1784.

- All Things Liberty, “James Lafayette (James Armistead): An American Spy.”

- Library of Virginia, “Testimonial of the Marquis de Lafayette on Behalf of James Armistead.”

- Acts of the Virginia General Assembly, 1787, Chap. 21, “An Act to Emancipate James, a Slave, for Services Rendered in the Late War.”

- Richmond Enquirer, October 1824, eyewitness report of Lafayette’s tour, reprinted by Library of Virginia Archives.

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).”

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).”

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette.”

- Library of Virginia, “Acts of the Virginia General Assembly, 1787, Chap. 21.”

- All Things Liberty, “James Lafayette (James Armistead): An American Spy.”

- History.com, “How a Slave Spy Helped Secure the American Victory at Yorktown.”

- Battlefields.org, “James Armistead Lafayette.”

- Library of Virginia, “Acts of the Virginia General Assembly, 1787, Chap. 21.”

- Richmond Enquirer, October 1824, eyewitness report of Lafayette’s tour, reprinted by Library of Virginia Archives.

- Encyclopedia Virginia, “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).”

Bibliography

- Acts of the Virginia General Assembly. 1787, Chap. 21. “An Act to Emancipate James, a Slave, for Services Rendered in the Late War.”

- All Things Liberty. “James Lafayette (James Armistead): An American Spy.” Accessed November 2025.

- Battlefields.org. “James Armistead Lafayette.” Accessed November 2025.

- Encyclopedia Virginia. “Lafayette, James Armistead (ca. 1748–1830).” Accessed November 2025.

- History.com. “How a Slave Spy Helped Secure the American Victory at Yorktown.” Accessed November 2025.

- Library of Virginia. “James Armistead Lafayette, Petition for Freedom, 1787.” Accessed November 2025.

- Library of Virginia. “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775.” Accessed November 2025.

- Library of Virginia. “Testimonial of the Marquis de Lafayette on Behalf of James Armistead.” November 21, 1784.

- Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia. “Lafayette’s Spies.” Accessed November 2025.

- RevWarApps.org. “James Armistead Lafayette, Revolutionary War Pension Application (VAS807).” Accessed November 2025.

- Richmond Enquirer. October 1824. Eyewitness report of Lafayette’s tour, reprinted by Library of Virginia Archives.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.