The American Revolution was not born on a battlefield but in the refusal to obey. Civil disobedience, as practiced by the American colonists, carried profound contradictions.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Moral Foundation of Rebellion

Civil disobedience, before it became a modern phrase of political virtue, was already a living force in the American colonies. In the decade before the Revolution, the British Empire faced not only petitions and debates but a growing refusal to obey. What began as scattered protests over paper stamps and import duties grew into an organized moral resistance, one that questioned not merely a tax but the nature of authority itself. The colonists’ defiance was not spontaneous anarchy; it was rooted in Enlightenment ideas about the social contract and the limits of legitimate rule, especially as articulated by John Locke, whose writings on consent and natural rights were widely circulated and cited in colonial pamphlets.1 By the 1770s, many colonists had come to view disobedience not as crime but as duty, a defense of liberty when obedience itself became a form of complicity.

The transformation of political loyalty into moral resistance marked a radical departure from traditional notions of protest. Civil disobedience in the colonial context blended principle with practicality: it was an ethic of refusal sustained by boycotts, symbolic acts, and, at times, violence.2 Each stage of this defiance (refusing to pay the Stamp Act tax, boycotting British goods, harassing royal officials, destroying taxed tea, and ultimately coordinating through the Continental Congress) revealed an evolution from grievance to revolution. Yet what unified these diverse actions was their shared conviction that unjust laws demanded disobedience, not compliance. This belief, both moral and strategic, became the crucible from which American independence was forged.

The earliest tests of conscience came with the Stamp Act of 1765, the first direct tax imposed by Parliament on the colonies.3 Resistance to it took the shape of mass refusals, boycotts of stamped goods, and riots that made enforcement nearly impossible. When Parliament repealed the act, it confirmed for the colonists that defiance could succeed, a lesson they would not forget. Over the next decade, new duties under the Townshend Acts of 1767 provoked boycotts that turned private consumption into a political weapon, as colonists refused British goods and promoted homespun fabrics to assert economic independence.4 The women who wove homespun cloth were not only supporting a boycott but enacting a quiet revolution in civic identity, binding domestic labor to public virtue.

By the early 1770s, civil disobedience took on more volatile forms. Angry crowds attacked Loyalist merchants and officials, seeing them as collaborators in oppression.5 The destruction of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s Boston mansion symbolized the emotional edge of the movement: outrage at the violation of rights mingled with a dangerous willingness to destroy the symbols of imperial power. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 then turned defiance into spectacle, fusing moral principle with theatrical rebellion as colonists dumped taxed tea into Boston Harbor to dramatize their claim that liberty could not coexist with arbitrary authority.6 Britain’s punitive reaction, the Intolerable Acts of 1774, sought to crush the spirit of disobedience but instead ignited it anew. The First Continental Congress, formed in that same year, transformed sporadic resistance into a continental movement, coordinating boycotts and noncompliance with imperial law across the colonies.7

By 1775, what had begun as acts of civil disobedience evolved into open revolution. The colonists had learned through experience that when petitions failed, resistance could be both just and effective. The philosophy of obedience had given way to the ethics of conscience; loyalty to the crown had yielded to loyalty to liberty. The Revolution was, in its first incarnation, not a war but a refusal, a refusal to obey unjust authority and a declaration that the moral law of freedom stood above the decrees of Parliament.8

The Stamp Act Crisis (1765–1766): Defying Imperial Authority through Refusal

When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in March 1765, few in London anticipated the fury it would provoke across the Atlantic. For the first time, the British government levied a direct tax on the colonies, requiring that legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards bear a purchased stamp.9 To the imperial mind, it was a modest measure to offset debts from the Seven Years’ War and fund defense of the colonies; to the colonists, it was an assault on their political rights. Without elected representatives in Parliament, taxation by decree was tyranny disguised as law. The cry of “no taxation without representation” was not a slogan born of convenience but the moral core of civil disobedience, the claim that obedience could not be compelled where consent had not been given.10

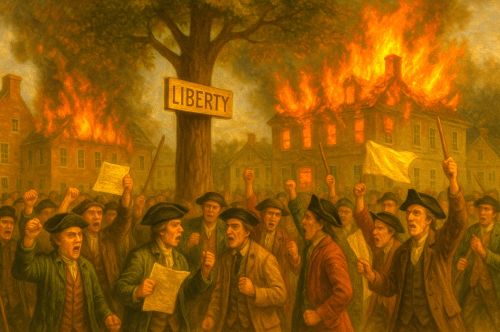

Resistance began not in violence but in organized refusal. Local assemblies denounced the law, newspapers condemned it, and ordinary citizens pledged to reject stamped goods. Across the colonies, agents appointed to distribute stamps resigned under public pressure or fled under threat of mob action. In Boston, effigies of tax officials were hanged from Liberty Trees, and public processions forced the resignation of Andrew Oliver, the designated stamp distributor for Massachusetts.11 When word of the widespread defiance reached London, the law had effectively collapsed in practice; courts could not function, merchants refused documentation, and customs officials faced a citizenry united in contempt.12

Out of this chaos came the Stamp Act Congress, convened in New York in October 1765, which represented one of the earliest acts of continental cooperation. Delegates from nine colonies met to draft formal declarations of rights and grievances, asserting that taxation without representation violated both the British Constitution and natural law. Their resolutions were careful yet revolutionary in implication; they affirmed allegiance to the crown but denied Parliament’s right to legislate for them in matters of taxation.13 Benjamin Franklin, testifying before Parliament the following year, summarized the sentiment of the colonies: they would “never submit to such taxation unless it was imposed by their own assemblies.”14 His testimony, circulated widely in the colonies, transformed defiance into legitimacy and confirmed the moral logic of resistance.

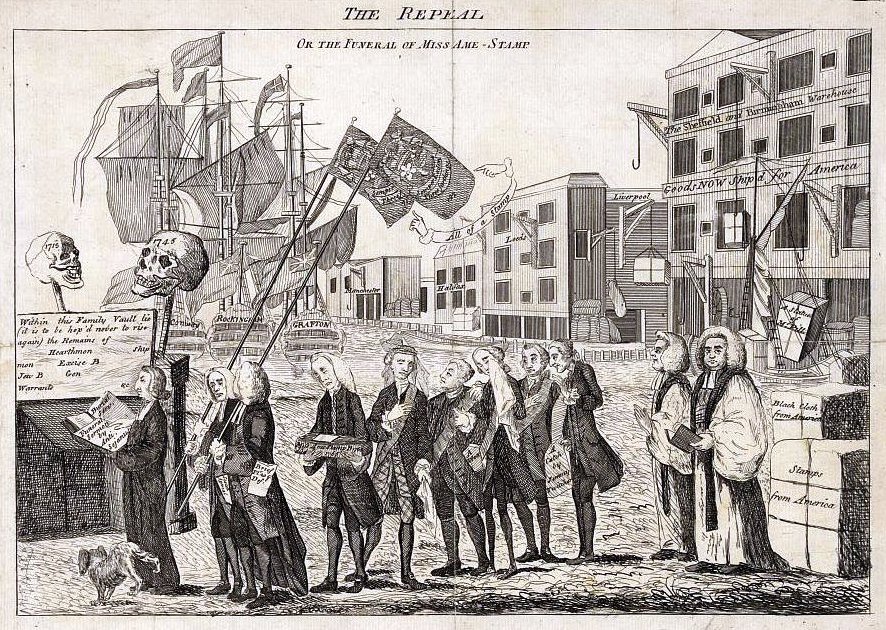

The repeal of the Stamp Act in March 1766 was celebrated as a triumph of collective will. Bells rang from New England to the Carolinas, and colonists toasted the “friends of liberty” in Parliament who had supported repeal. Yet beneath the celebration lay a critical lesson: civil disobedience worked. By refusing to comply, the colonists had rendered an act of Parliament unenforceable without ever formally renouncing the crown.15 This success set a precedent, when obedience was withdrawn from unjust authority, that authority faltered. The idea that moral refusal could serve as a political weapon had taken root. The same networks of protest that mobilized against the Stamp Act would soon be revived against new impositions, refined and expanded into an economic and ideological system of resistance that bound the colonies together more tightly than British rule ever had.16

Boycotts and the Townshend Acts (1767–1770): The Economics of Resistance

If the Stamp Act crisis had tested the colonists’ moral resolve, the Townshend Acts of 1767 tested their endurance. Imposed under the leadership of Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend, these acts placed import duties on glass, paper, paint, lead, and tea, all everyday goods that tied colonial households to British commerce.17 While the revenue raised was relatively small, the principle behind it was intolerable: Parliament had reasserted its right to tax without representation. This time, the colonists’ response would expand beyond symbolic refusal; it would become an organized, economic campaign of noncompliance.

Across the colonies, nonimportation agreements began as local pledges and evolved into a form of coordinated civil disobedience. Merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia agreed not to import British goods until the duties were repealed, transforming consumption into a moral and political act.18 Newspapers published the names of those who violated the boycotts, turning commerce into conscience and social reputation into enforcement. The movement extended into domestic life, where colonial women emerged as political actors through the homespun movement, producing local textiles to replace imported British cloth.19 Their work symbolized independence through self-sufficiency and elevated household labor to an expression of patriotic virtue.

John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1767–1768) gave this resistance its intellectual form. A respected lawyer and legislator, Dickinson argued that while Parliament retained authority to regulate trade, it had no moral or constitutional right to levy duties for revenue. His essays, printed and reprinted throughout the colonies, framed the boycotts not as rebellion but as lawful self-defense, obedience to a higher conception of justice.20 For the first time, the colonial public sphere fused economic action with moral reasoning. Civil disobedience was no longer the domain of radicals; it had become the language of respectable dissent.

The boycotts also revealed how deeply the empire’s authority depended on compliance. British merchants, alarmed by plummeting exports, lobbied Parliament to repeal the duties, just as they had after the Stamp Act.21 The British government relented partially in 1770, repealing all Townshend duties except the one on tea, a symbolic gesture meant to preserve parliamentary supremacy.22 But the damage to imperial legitimacy was done. The colonies had discovered a weapon that required no armies or declarations, only the collective withdrawal of consent. The politics of consumption had become the politics of freedom, and the act of buying or refusing to buy was now a declaration of conscience.

This period also fostered a new sense of intercolonial identity. Committees of correspondence circulated news of enforcement, and resistance rhetoric increasingly referred to the colonies as a united people.23 Even as the boycotts waned following the partial repeal, their effect endured: civil disobedience had become institutionalized. It had proven capable not only of defying unjust laws but of building solidarity through shared sacrifice. By substituting obedience with restraint, the colonists had created a republic of conscience within an empire of authority, a fragile equilibrium that could not last.

Violence and Vengeance: Attacks on Loyalists and the Erosion of Order (1765–1773)

By the early 1770s, the moral discipline of civil disobedience had begun to blur with the unruly energy of mob justice. The same passions that had driven organized boycotts and petitions now turned toward direct confrontation with those seen as agents of imperial oppression. Civil disobedience, as practiced in the colonial towns, was no longer confined to symbolic refusal or economic restraint. It spilled into the streets, targeting Loyalists, customs officials, and merchants accused of betraying the cause of liberty. The line between resistance and rebellion began to fade, and acts of protest acquired a violent urgency born of frustration with unyielding authority.24

The destruction of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s Boston mansion in August 1765 marked a turning point in the emotional tenor of colonial defiance. Mobs, angered by the Stamp Act and by Hutchinson’s perceived complicity in its enforcement, broke into his home, destroyed furniture, and scattered his extensive library.25 Hutchinson, a learned and cautious man, had never supported the act publicly, yet his status as a royal official made him a symbol of the system the colonists sought to resist. To many patriots, the violence was regrettable but justified, a rough expression of the same moral outrage that inspired boycotts and petitions.26 To others, it revealed the dangerous volatility of a movement that could no longer contain its passions within the bounds of law.

As resistance deepened through the late 1760s, intimidation of Loyalist merchants and public officials became common. Boston’s “Sons of Liberty” and similar groups elsewhere enforced nonimportation agreements through public shaming, effigy burnings, and forced recantations.27 Shops that sold British goods were targeted for vandalism; outspoken Loyalists risked tarring and feathering, a ritualized form of humiliation designed to mark moral betrayal as vividly as physical punishment. These episodes were not random outbreaks of rage but political theater, intended to dramatize the moral boundaries of the community. By defining who was loyal to liberty and who was not, they turned disobedience into a test of civic virtue. Yet the growing reliance on coercion hinted at a paradox: in defending liberty, patriots were increasingly willing to suspend it.28

Violence also spread through smaller towns and rural communities, where imperial authority was weakest. Tax collectors, customs officials, and informants were driven from their posts; in places like Rhode Island and New York, riots erupted over the seizure of colonial ships suspected of smuggling.29 The 1772 Gaspee affair, in which Rhode Island colonists burned a British customs schooner, dramatized how local resistance could now escalate into direct attacks on the instruments of royal power.30 The colonial governments that had once enforced obedience were losing legitimacy, replaced by ad hoc committees and assemblies answerable to the people rather than the crown. The civil part of civil disobedience was being overshadowed by the revolutionary.

Even among leaders sympathetic to the cause, the violence produced anxiety. John Adams, reflecting on the destruction of Hutchinson’s property, worried that “popular excess” might erode public sympathy for resistance.31 Samuel Adams, more radical in temperament, sought to channel the anger of the people into organized protest, arguing that liberty was always endangered when passion was suppressed by deference.32 These debates within the patriot ranks mirrored a larger philosophical tension: whether justice could still be served through restraint when authority itself had become lawless. The colony that tolerated arbitrary taxation, they reasoned, could not forever forbid its people from acting in defiance.

By 1773, the moral equilibrium that had once guided protest gave way to a conviction that action itself was virtue. The memory of peaceful petitions and reasoned debate faded as colonists increasingly viewed the struggle as existential. The moral framework of civil disobedience remained, obedience to conscience over unjust power, but its expression had grown militant. When Parliament next attempted to enforce its will through the Tea Act, the colonists would no longer seek compromise. The movement that had begun with pamphlets and boycotts was now prepared to stage rebellion as a moral performance.33

The Boston Tea Party (1773): Symbolic Defiance and the Politics of Principle

When Parliament passed the Tea Act of 1773, it believed it was offering the colonies a favor, a cheaper commodity that would rescue the struggling East India Company and subtly reaffirm parliamentary authority. The act allowed the company to sell tea directly to the colonies without paying intermediate British taxes, effectively undercutting local merchants.34 To imperial officials, it was a pragmatic measure; to colonial radicals, it was a trap. By accepting the tea, the colonists would concede Parliament’s right to tax them. The principle was simple yet absolute: a cheap tyranny was still tyranny. What emerged in response was not merely protest but a moral spectacle, an act of civil disobedience designed to dramatize the incompatibility of liberty and submission.

Boston became the epicenter of confrontation. In November 1773, three ships (the Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver) arrived in the harbor loaded with East India Company tea.35 Town meetings were held daily to decide the fate of the cargo. Governor Hutchinson, determined to assert imperial authority, refused to allow the ships to leave without unloading and paying the duty. For weeks, tension mounted as patriots, led by Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, insisted that the tea be sent back to England. The confrontation reached its climax on the night of December 16, when a group of men, many disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded the ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor.36 They destroyed property, yet stole nothing; they broke the law, yet acted with a discipline that elevated the event above riot. In its restraint lay its power: the destruction of the tea was a moral performance of disobedience, not plunder.

The Boston Tea Party reverberated throughout the colonies and across the Atlantic. British observers viewed it as an outrageous insult to royal authority, while many colonists saw it as a courageous assertion of principle.37 The participants understood their act as a defense of constitutional rights rather than an act of rebellion. Newspapers hailed the destruction of the tea as a patriotic necessity, a visible declaration that submission to arbitrary taxation would never be accepted. The symbolism was unmistakable: where Parliament had imposed order by law, the colonists restored moral order through defiance. The harbor’s darkened water, tinged with floating tea, became a baptismal scene in which the American conscience was reborn.

Britain’s response, however, transformed this moment of defiance into a revolutionary turning point. In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts, closing Boston Harbor, revoking Massachusetts’s charter, and allowing royal officials accused of crimes to be tried in England.38 These measures, intended to isolate Massachusetts, united the colonies in outrage. Far from restoring obedience, the punishment confirmed that the British government viewed civil disobedience not as a moral plea but as treason. The Tea Party thus marked both an end and a beginning: the end of illusion that reconciliation could coexist with liberty, and the beginning of a revolution grounded in the belief that conscience itself could be the foundation of law.39

The First Continental Congress (1774): From Dissent to Unity

When the news of the Coercive Acts reached the colonies in mid-1774, it ignited a political and moral crisis that made unity not merely desirable but necessary. The punitive laws (closing Boston Harbor, placing Massachusetts under military control, and authorizing the quartering of troops) were understood as collective punishment for collective disobedience.40 For colonists who had once imagined themselves loyal British subjects, this response confirmed their deepest fears: civil disobedience, no matter how principled, would be met with coercion, not compromise. The colonies’ choice was now between submission and solidarity. The call for a Continental Congress spread rapidly through the Committees of Correspondence, linking distant provinces in a shared recognition that resistance must be organized, not improvised.41

In September 1774, delegates from twelve colonies assembled at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, marking the first truly continental act of political cooperation in American history.42 The gathering was cautious but resolute. Its members (among them George Washington, John Adams, Patrick Henry, and John Jay) did not yet speak of independence. They came instead to articulate a common defense of rights and to seek redress through collective pressure. The Congress’s proceedings were conducted with deliberate formality, invoking both the legal decorum of Parliament and the moral weight of the English common-law tradition. Yet beneath the language of loyalty ran a current of defiance: if Parliament could legislate without consent, then the moral contract binding subjects to rulers was already broken.43

The most significant product of the Congress was the Continental Association, adopted on October 20, 1774.44 It established a comprehensive boycott of British goods, imports, and exports, and created local committees to enforce compliance. This was civil disobedience elevated to an institution, a moral economy governed by principle rather than profit. Through it, disobedience became organized into a system of governance parallel to British authority. Merchants, farmers, and townspeople participated not as subjects but as citizens enforcing their own collective laws. The Association’s preamble explicitly appealed to “the immutable laws of nature” and to the rights of Englishmen, fusing Enlightenment theory with lived resistance.45 It represented a revolutionary act in disguise: a lawful framework for coordinated illegality.

The Congress also issued the Declaration and Resolves, asserting that the colonists retained the same rights as subjects in Britain, including the right not to be taxed without consent and the right to self-government in local affairs.46 While the tone remained conciliatory, professing loyalty to King George III, it was, in substance, a manifesto of self-legitimization. Civil disobedience had matured into constitutional reasoning. The delegates rejected violence yet affirmed the moral duty to resist unjust authority. What had once been spontaneous protest now possessed a collective voice, capable of defining both grievance and remedy. The Congress embodied the paradox of the moment: a revolutionary body that denied it was revolutionary.

By the time the delegates adjourned in late October, the nature of colonial opposition had been transformed. The boycotts and petitions of earlier years had prepared the ground; now, civil disobedience stood as an organized alternative to imperial governance.47 When the Second Continental Congress reconvened the following year after blood had been spilled at Lexington and Concord, the logic of unity would evolve into the logic of independence. But in 1774, the First Continental Congress represented the culmination of a decade of moral resistance, the moment when defiance became a system, and conscience began to govern where empire had failed.48

The Intolerable Acts and the Point of No Return (1774–1775): Civil Disobedience becomes Revolution

The Intolerable Acts, as the colonists called them, were intended to crush rebellion but instead ignited it. The closing of Boston Harbor under the Boston Port Act, the dissolution of Massachusetts’s self-government through the Massachusetts Government Act, and the authorization for British troops to be quartered in private homes through the Quartering Act convinced many colonists that civil disobedience was no longer a temporary necessity but a moral imperative.49 The laws were collectively perceived not as legal statutes but as instruments of domination, evidence that Britain had abandoned any pretense of constitutional restraint. Civil disobedience, once a protest against taxation, now became a defense of self-government itself.

Across New England, defiance turned into open organization. Local communities formed Committees of Correspondence and Committees of Safety, assuming powers once held by royal governors and legislatures.50 Town meetings, once subject to strict regulation, became revolutionary assemblies that coordinated boycotts, collected supplies, and drilled local militias. In Massachusetts, the newly formed Provincial Congress effectively replaced royal authority by late 1774, preparing for armed defense while still professing loyalty to the crown.51 The paradox of this moment, revolution under the guise of fidelity, defined the final phase of colonial resistance. The colonists were not yet ready to declare independence, but their refusal to submit had rendered imperial rule impossible.

The Intolerable Acts also galvanized the other colonies, transforming sympathy for Massachusetts into shared resolve. The closing of Boston Harbor became a national symbol of oppression; food, money, and supplies poured in from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Carolinas.52 Newspapers throughout the colonies compared Boston’s plight to the siege of ancient cities whose liberty had been extinguished by tyranny. This moral rhetoric was crucial; it cast the conflict not in political but in civilizational terms, as a struggle between freedom and despotism. In uniting around Massachusetts, the colonies discovered themselves as a single moral community. Disobedience had ceased to be a series of local acts and become a collective conscience.

By early 1775, British commanders recognized that authority existed only where troops could enforce it. General Thomas Gage, governor of Massachusetts, fortified Boston and attempted to seize colonial munitions at Concord, an action that would trigger the first shots of war.53 When the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord erupted on April 19, the philosophical question of obedience to unjust authority was answered in musket fire. The colonists had moved from civil disobedience to armed defense, but the moral foundation remained the same: they fought not to destroy law, but to restore the principle that law derived from consent.54 In their minds, the Revolution was less an act of rebellion than the completion of their long campaign of resistance by other means.

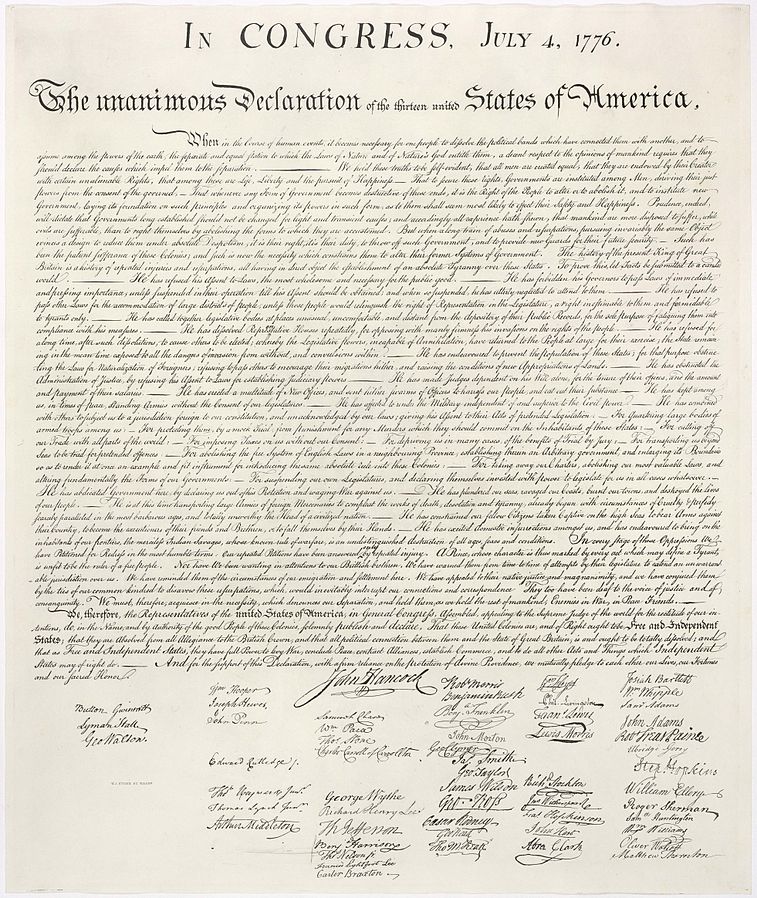

Looking back from that fateful spring, it is clear that the Revolution did not begin with independence but with disobedience. The decade between 1765 and 1775 had taught the colonists that political legitimacy could be withdrawn as surely as it could be granted. Through petitions, boycotts, and acts of moral defiance, they redefined authority as conditional and freedom as natural.55 When the Declaration of Independence was finally adopted the following year, it was not a departure from their past but its logical conclusion, the codification of a principle they had already lived. Civil disobedience had matured into revolution, and the conscience of a people had become the charter of a nation.56

Conclusion: From Lawbreakers to Founders

The American Revolution was not born on a battlefield but in the refusal to obey. The decade of protest preceding independence transformed the moral language of the colonies from that of loyal grievance to one of sovereign conscience. From the Stamp Act Crisis through the Intolerable Acts, each act of disobedience pushed the colonists further toward a recognition that liberty could not coexist with passive submission. Their defiance was not anarchic but deeply principled, an appeal to natural law and inherited rights rather than rebellion for its own sake. When they withheld obedience, they were asserting that government without consent was not government at all. In this, the colonists were heirs to the Enlightenment but also innovators, fusing the European philosophy of rights with a distinctly American practice of collective resistance.

The progression of civil disobedience throughout the 1760s and 1770s reveals a remarkable moral evolution. The early boycotts and refusals were defensive, aimed at restoring a violated compact. Yet as Parliament answered protest with punishment, conscience hardened into conviction. What began as an argument for participation within the empire became a claim to independence from it. The colonists did not set out to create a new nation; they sought to preserve the moral order that they believed British corruption had betrayed. But in defending the ancient liberties of Englishmen, they discovered the universal rights of humankind. Their revolution was thus both conservative and radical: conservative in its reverence for principle, radical in its insistence that principle could nullify power.

Civil disobedience, as practiced by the American colonists, carried profound contradictions. It demanded restraint even as it invited disorder; it appealed to law even as it defied it. Yet those contradictions proved its strength. The willingness to suffer consequences, to act without violence where possible but without submission where necessary, gave moral legitimacy to political resistance. In refusing to comply, the colonists did not abandon law; they redefined it. Law was no longer the decree of authority but the embodiment of justice. By aligning moral obligation with political action, they demonstrated that conscience could be both the origin and the limit of power.

In the end, the Revolution stands as the natural culmination of a decade-long experiment in moral courage. The petitions, boycotts, and protests that preceded Lexington and Concord were rehearsals in self-government, training a people to think and act as free citizens. When the Continental Congress declared independence in 1776, it merely articulated what had already been proven through practice, that the ultimate authority in political life resides not in rulers but in the governed. Civil disobedience was the seed of that revelation. It transformed lawbreakers into founders and transformed defiance into a declaration. The United States was born not from obedience to empire but from obedience to conscience, and in that act of refusal lay the true beginning of American freedom.

Appendix

Footnotes

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (London: Awnsham Churchill, 1690), II, §§149–168.

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 4–6.

- “Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress,” October 19, 1765, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington: Library of Congress).

- T.H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 115–118.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), 261–265.

- Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 73–77.

- “The Continental Association,” October 20, 1774, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1991), 25–27.

- “An Act for Granting and Applying Certain Stamp Duties,” 5 Geo. III, c.12 (1765), in The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 26 (London: Charles Bathurst, 1767).

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 105–107.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 33–38.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 176–179.

- “Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress,” October 19, 1765, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington: Library of Congress).

- “Examination of Dr. Benjamin Franklin before an August Assembly,” The London Chronicle, February 1766, reprinted in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 13 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969).

- Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), 29–30.

- Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution, 52–54.

- “An Act for Granting Certain Duties in the British Colonies and Plantations in America,” 7 Geo. III, c.46 (1767), in The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 29 (London: Charles Bathurst, 1768).

- “Merchants’ Non-Importation Agreement,” Boston, August 1, 1768, in Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States, ed. Charles C. Tansill (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1927), 1–3.

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 27–31.

- John Dickinson, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies (Philadelphia: David Hall and William Sellers, 1768), Letter II.

- Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution, 176–179.

- Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789, 38–39.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 115–118.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 102–104.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 187–189.

- Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789, 44–45.

- Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 19–23.

- Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 48–51.

- Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 85–88.

- “Deposition of Joseph Bucklin and Ephraim Bowen,” June 1772, in The Gaspee Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, Vol. 5 (Providence: 1882), 23–26.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams, Vol. 2 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1850), 156.

- Samuel Adams to James Warren, August 24, 1772, in The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing, Vol. 3 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907), 88.

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 41–43.

- “An Act to Allow a Drawback of the Duties of Customs on the Exportation of Tea,” 13 Geo. III, c.44 (1773), in The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 31 (London: Charles Bathurst, 1774).

- “Boston Town Meeting Minutes, November 29–30, 1773,” in The Boston Town Records, 1770–1777, ed. Samuel F. Drake (Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1884), 123–125.

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 77–82.

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 198–200.

- Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause, 112–115.

- Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 58–61.

- “An Act for the Better Regulating the Government of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay,” 14 Geo. III, c.45 (1774), in The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 31 (London: Charles Bathurst, 1774).

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 221–224.

- “Journal of the Proceedings of the First Continental Congress,” September 5–October 26, 1774, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington: Library of Congress).

- Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), 61–63.

- “The Continental Association,” October 20, 1774, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789.

- Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution, 230–233.

- “Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress,” October 14, 1774, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789.

- Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789, 49–52.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 127–130.

- “An Act for the Better Regulating the Government of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay,” 14 Geo. III, c.45 (1774), in The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 31 (London: Charles Bathurst, 1774).

- Maier, From Resistance to Revolution, 233–236.

- Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause, 124–127.

- Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), 56–58.

- “Letter from General Thomas Gage to Lord Dartmouth, April 22, 1775,” in The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage, Vol. 2 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), 184–186.

- Rakove, Revolutionaries, 74–76.

- Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 145–149.

- Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 70–73.

Bibliography

- “An Act for Granting and Applying Certain Stamp Duties.” 5 Geo. III, c.12 (1765). In The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 26. London: Charles Bathurst, 1767.

- “An Act for Granting Certain Duties in the British Colonies and Plantations in America.” 7 Geo. III, c.46 (1767). In The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 29. London: Charles Bathurst, 1768.

- “An Act to Allow a Drawback of the Duties of Customs on the Exportation of Tea.” 13 Geo. III, c.44 (1773). In The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 31. London: Charles Bathurst, 1774.

- “An Act for the Better Regulating the Government of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay.” 14 Geo. III, c.45 (1774). In The Statutes at Large from Magna Charta to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Vol. 31. London: Charles Bathurst, 1774.

- “Boston Town Meeting Minutes, November 29–30, 1773.” In The Boston Town Records, 1770–1777. Edited by Samuel F. Drake. Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1884.

- “Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress.” October 14, 1774. In Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Washington: Library of Congress.

- “Journal of the Proceedings of the First Continental Congress.” September 5–October 26, 1774. In Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Washington: Library of Congress.

- “Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress.” October 19, 1765. In Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Washington: Library of Congress.

- “The Continental Association.” October 20, 1774. In Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Washington: Library of Congress.

- Adams, John. The Works of John Adams. Edited by Charles Francis Adams. Vol. 2. Boston: Little, Brown, 1850.

- Adams, Samuel. The Writings of Samuel Adams. Edited by Harry Alonzo Cushing. Vol. 3. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Breen, T.H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Bucklin, Joseph, and Ephraim Bowen. “Deposition of Joseph Bucklin and Ephraim Bowen.” June 1772. In The Gaspee Papers. Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, Vol. 5. Providence, 1882.

- Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Dickinson, John. Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies. Philadelphia: David Hall and William Sellers, 1768.

- Franklin, Benjamin. “Examination of Dr. Benjamin Franklin before an August Assembly.” The London Chronicle, February 1766. Reprinted in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 13. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969.

- Gage, Thomas. “Letter from General Thomas Gage to Lord Dartmouth, April 22, 1775.” In The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage, Vol. 2. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933.

- Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. London: Awnsham Churchill, 1690.

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Morgan, Edmund S. The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1789. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956.

- Nash, Gary B. The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Rakove, Jack. Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

- Tansill, Charles C., ed. Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1927.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1991.

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.