Progressive Christianity developed through a long trajectory of reform movements that challenged injustice and reshaped Christian tradition.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Progressive Christianity is often described as a recent development in American religious life, yet historians trace its origins to a much longer tradition of reform movements that challenged unjust social structures and reinterpreted Christian faith in light of moral responsibility. From the abolitionist preachers of the nineteenth century to the theologians who applied critical scholarship to biblical texts, early reformers reshaped Christian practice by urging believers to place ethical action and social transformation at the center of religious life.1 These movements questioned inherited doctrines and emphasized a form of Christianity rooted in compassion, justice, and the dignity of every human being.

The emergence of higher criticism in the nineteenth century provided another foundation for what would later be recognized as progressive Christian thought. Scholars such as David Friedrich Strauss approached the Bible through historical inquiry and literary analysis, treating scriptural texts as products of particular cultural contexts rather than as literal historical records.2 This intellectual shift challenged traditional interpretations of scripture and encouraged a more expansive engagement with the moral and ethical teachings of Christianity. Liberal Protestantism in Europe and the United States absorbed many of these ideas and applied them to debates about slavery, inequality, and religious authority.

By the early twentieth century, these traditions converged within the Social Gospel movement, which articulated one of the first theologically organized efforts to address industrial poverty, labor exploitation, and urban misery. Walter Rauschenbusch argued that Christian ethics demanded systemic reform and a renewed commitment to alleviating suffering caused by social and economic structures.3 His work reflected a broader conviction that the teachings of Jesus provided a framework for confronting injustice and transforming public life. The Social Gospel did not resolve all of its internal tensions, but it established a sustained theological presence that linked Christian faith to social responsibility.

These earlier reform movements laid the groundwork for later expressions of progressive Christianity that emerged during the civil rights era, the growth of liberation theologies, and the expansion of feminist and queer theologies in the late twentieth century. Although these movements differed in scope and emphasis, they shared a commitment to challenging structures of oppression and reimagining Christian teachings in ways that affirmed human dignity and promoted justice. Their influence continues to shape contemporary progressive Christian communities that respond to present-day issues such as racial inequality, immigration, and political extremism while drawing inspiration from the long history of reformist Christian thought.

Nineteenth-Century Precursors: Abolition, Higher Criticism, and Liberal Protestantism

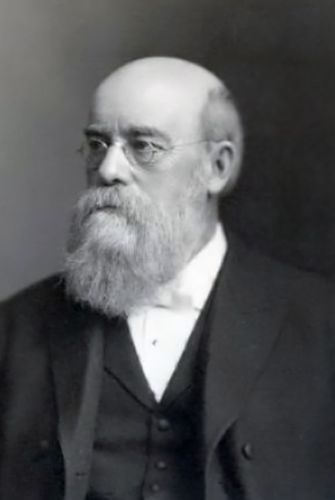

Progressive Christianity’s earliest foundations can be traced to the abolitionist movements of the nineteenth century, where Christian moral arguments were deployed against the institution of slavery. Theodore Dwight Weld insisted that slavery contradicted biblical principles of human dignity, emphasizing the incompatibility between Christian ethics and racial bondage.4 Abolitionists such as Weld, the Grimké sisters, and other reformers treated Christianity as a moral force capable of challenging entrenched systems of injustice. Their theological arguments gained further weight from the writings of formerly enslaved people. Frederick Douglass, for example, distinguished sharply between the Christianity of Christ and what he described as the corrupt, slaveholding religion of the United States.5 These critiques formed an early strand of what would later be recognized as progressive Christian thought grounded in justice and human liberation.

At the same time, European and American theologians were reexamining biblical interpretation through the tools of historical criticism. German scholars, including David Friedrich Strauss, challenged traditional readings of scripture by treating biblical narratives as historical and literary products rather than as inerrant accounts. Strauss’s Life of Jesus Critically Examined argued for understanding the Gospels within their first-century contexts and questioned long-held assumptions about their literal meaning.6 His work was controversial, but it helped open a new space for theological inquiry that emphasized reason, historical consciousness, and intellectual honesty. These currents shaped the development of liberal Protestantism, especially in academic and ecclesial settings that welcomed critical engagement with scripture.

The emergence of the documentary hypothesis later in the century further transformed Christian scholarship. Julius Wellhausen’s Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel proposed that the Pentateuch had multiple authors and had developed over centuries, a claim based on linguistic, thematic, and historical analysis.7 Although many clergy resisted these findings, others incorporated them into a theological framework that emphasized ethical teachings rather than strict adherence to traditional doctrines. This shift encouraged Christians to engage scripture as a dynamic record of evolving religious understanding, a perspective that aligned closely with the reformist tendencies that would characterize later progressive movements.

These developments unfolded alongside broader currents in American and British liberal Protestantism. Thinkers within these traditions emphasized the moral teachings of Christianity, prioritized conscience over dogmatic authority, and encouraged a faith responsive to social change. Gary Dorrien has shown that nineteenth-century liberal theology placed strong emphasis on ethical living, personal transformation, and public engagement.8 This constellation of abolitionist activism, critical biblical scholarship, and ethical reform produced a distinct intellectual environment in which progressive Christianity would eventually take shape. The combination of moral critique and theological openness made it possible for later movements to challenge injustice while remaining grounded in a constructive Christian tradition.

The Social Gospel Movement and Early Twentieth-Century Christian Reform

The rise of industrial capitalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries created new social conditions that demanded a theological response. Factories, crowded cities, low wages, and dangerous working environments brought widespread poverty and exploitation. Reform-minded clergy increasingly argued that Christian ethics could not remain confined to personal morality when entire communities faced structural injustice. Washington Gladden, a Congregational minister, articulated some of the earliest arguments that Christianity required public responsibility for the conditions created by industrialization.9 His focus on labor rights and ethical business practices represented a shift toward understanding the Gospel as a mandate for social improvement rather than a purely personal creed.

Walter Rauschenbusch provided the most influential theological expression of this movement. Working in the impoverished Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of New York City, he witnessed firsthand the consequences of economic inequality and urban neglect. His A Theology for the Social Gospel argued that systemic sin manifested in institutions and social structures rather than solely in individual behavior.10 This analysis encouraged Christians to focus on transforming economic systems, legal policies, and community practices in ways that reflected justice and compassion. By situating sin within social reality, Rauschenbusch offered a framework that connected Christian theology to collective reform.

Reform efforts took tangible institutional forms that shaped the practice of American Protestantism. Churches established settlement houses, community centers, and social programs aimed at assisting immigrants, workers, and impoverished families. The movement also influenced national organizations, including the Federal Council of Churches, which issued the Social Creed of the Churches in 1908. The Creed articulated commitments to labor protections, fair wages, and the reduction of poverty.11 Its adoption by major Protestant denominations marked a significant moment in the integration of social ethics into American Christian identity and provided an authoritative statement of the Social Gospel’s goals.

The Social Gospel also shaped wider political and civic activism. Many reformers supported labor unions, public health initiatives, and anti-poverty campaigns, framing these actions as expressions of Christian responsibility. Their theological vision inspired activists who believed that religious faith should inform public life and contribute to the creation of a more just society. Christopher Evans has shown that these reformers influenced later movements, including mid-century civil rights activism, by grounding social change in Christian ethical commitments.12 The movement therefore created a bridge between nineteenth-century liberal theology and later forms of socially engaged Christianity.

Despite internal disagreements and criticism from theological conservatives, the Social Gospel left a lasting imprint on Christian thought and practice. By insisting that Christian ethics addressed social, economic, and political conditions, reformers established a model of Christian engagement that remains central to contemporary progressive Christianity. Their commitment to structural change, combined with their belief in the transformative potential of the Gospel, provided later generations with a framework for interpreting faith through the lens of justice. The Social Gospel did not resolve all the tensions within American Protestantism, but it expanded the boundaries of Christian discourse and redirected attention toward the moral dimensions of public life.

Mid-Century Movements: Civil Rights Christianity and Liberation Theology

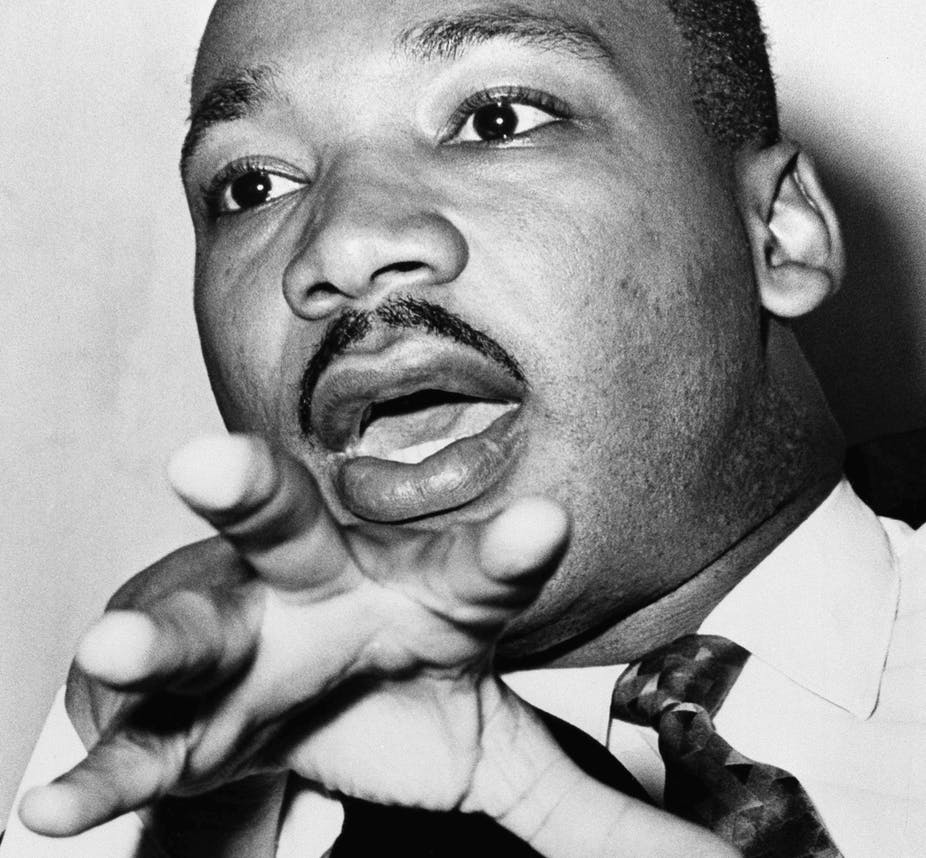

The mid-twentieth century witnessed a renewal of Christian engagement with social justice as civil rights activism confronted entrenched racial segregation and discrimination. Black church traditions had long linked faith to the pursuit of freedom, drawing on biblical narratives of liberation and prophetic calls for justice. Within this context, Christian leaders argued that segregation violated both moral law and the teachings of Jesus. Martin Luther King Jr. articulated this theological vision through sermons and essays that grounded civil rights work in Christian ethics. His Letter from Birmingham Jail insisted that unjust laws contradicted divine justice and that Christians bore moral responsibility to resist them.13 King’s arguments connected personal faith with collective action, shaping a religious framework that challenged the social and political order of the United States.

King’s approach reflected the broader influence of American Black church traditions, which had developed a theology that emphasized dignity, solidarity, and resistance. These traditions provided spiritual and organizational foundations for the civil rights movement. Churches served as meeting places, training centers for nonviolent activism, and sources of moral encouragement. Their leaders framed the struggle against segregation as part of a long history of Christian responsibility to confront injustice. Scholars such as James Cone later drew upon these traditions to articulate Black liberation theology, which interpreted the Gospel through the experiences of oppressed communities.14 Cone argued that Christian faith demanded solidarity with the marginalized and that the struggle for racial justice expressed a central truth of the Gospel.

Black liberation theology inspired and paralleled developments in other parts of the world. In Latin America, theologians responded to widespread poverty and political repression by reexamining the relationship between faith and social structures. Gustavo Gutiérrez’s A Theology of Liberation, first published in 1971, grounded Christian ethics in the lived experiences of the poor and insisted that social transformation was integral to the practice of faith.15 His work emphasized that liberation involved both spiritual renewal and material change, and it called for an examination of the economic and political systems that perpetuated inequality. This approach reshaped theological discourse in Catholic and Protestant communities throughout Latin America.

The influence of liberation theology extended beyond theology proper and affected Catholic institutional life. The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) encouraged renewed engagement with the modern world and affirmed the importance of social and economic justice. Documents such as Gaudium et Spes emphasized human dignity and the need for the Church to address contemporary social issues.16 Although not a liberation text itself, the Council helped create an environment in which Catholic theologians and clergy felt encouraged to pursue new approaches to Christian ethics. The Council’s emphasis on human rights and its affirmation of global responsibility provided theological support for reform movements that emerged in the decades that followed.

Movements for justice during this period also intersected with opposition to militarism and war. Christian activists argued that the ethical teachings of Jesus required resistance to violence and unjust conflict. The Vietnam War provoked significant Christian critique of American foreign policy, with many theologians and clergy urging the Church to adopt a more explicit stance on peace and international justice. These arguments drew upon older pacifist traditions as well as newer theological frameworks that connected military policy to broader questions of structural injustice. The emphasis on peace became a key component of progressive Christian thought, shaping public debates and institutional responses throughout the late twentieth century.

By the end of the twentieth century, liberation theologies had become central to the development of progressive Christianity. Their influence extended into academic theology, congregational life, and global Christian activism. These movements emphasized that faith required engagement with economic, political, and racial injustices, and they challenged the idea that Christianity could remain separate from public life. Liberation theologies encouraged Christians to interpret scripture in light of lived experiences, especially those marked by oppression, and they created a foundation for later movements that addressed gender equality, ecological concerns, and LGBTQ inclusion. Their impact ensured that questions of justice and solidarity remained central to progressive Christian thought.

Late Twentieth-Century Expansion: Feminist, Queer, and Ecological Theologies

The late twentieth century saw a widening of progressive Christian thought as theologians began to examine the ways gender shaped both religious experience and the interpretation of scripture. Feminist theologians argued that Christian traditions had long marginalized women’s voices and often reinforced patriarchal structures. Rosemary Radford Ruether offered one of the earliest systematic critiques of this dynamic in Sexism and God-Talk, where she argued that theology could not be credible if it ignored the full humanity of women.17 Her work called for a reconstruction of Christian doctrine that took women’s experiences seriously and challenged assumptions embedded in ecclesiastical authority, biblical interpretation, and liturgical practice. Ruether’s approach reflected a broader movement that sought to integrate feminist insights into every dimension of Christian theology.

Parallel to these developments, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza advanced a historical and exegetical project aimed at recovering the roles of women in early Christian communities. Drawing on careful analysis of biblical texts and early Christian history, she argued in In Memory of Her that women were active participants in the formation of the earliest churches.18 Her work challenged long-standing assumptions about the male-dominated nature of early Christianity and encouraged theologians and clergy to reconsider both historical interpretations and contemporary structures of authority. This historical dimension of feminist theology provided an important foundation for later efforts to create inclusive practices within churches.

Womanist theology emerged as another significant development during this period, grounded in the experiences of Black women who faced the combined forces of racism, sexism, and economic inequality. Delores Williams’s Sisters in the Wilderness offered a theological framework that drew on the story of Hagar and highlighted the survival strategies of marginalized women.19 Williams argued that traditional theological interpretations often overlooked or distorted the experiences of Black women and that a more accurate reflection of Christian ethics required attention to the realities of oppression as experienced across intersecting identities. Womanist theology expanded the reach of progressive Christianity by offering distinctive perspectives shaped by race, gender, and social context.

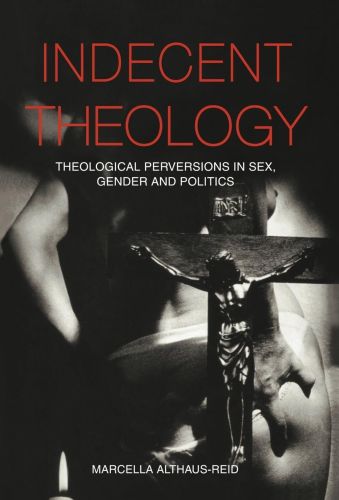

Queer theology developed during the same period, challenging conventional assumptions about sexuality and Christian identity. Marcella Althaus-Reid questioned prevailing theological norms by highlighting the ways in which sexual diversity had been excluded from Christian discourse. In Indecent Theology, she argued that theology loses credibility when it ignores bodies, desires, and lived experiences that do not fit traditional categories.20 Her work encouraged scholars to reconsider how Christian doctrine interacts with sexuality and to explore forms of theology that affirm LGBTQ identities. This approach broadened the scope of progressive theology by addressing areas that had previously remained on the margins of Christian reflection.

Ecological theology also emerged as a growing concern among progressive Christians. Theologians argued that modern crises related to climate, resource depletion, and environmental degradation required a Christian ethical response. Sallie McFague’s The Body of God articulated a model in which the world itself was understood as the embodiment of divine presence.21 This metaphorical approach encouraged Christians to reinterpret creation not as a resource for human exploitation but as a relational community deserving of care and protection. Ecotheology linked environmental ethics to Christian practice and contributed to the formation of religious movements focused on sustainability, stewardship, and global justice.

These diverse movements collectively reshaped the landscape of late twentieth-century progressive Christianity. They expanded the concerns of earlier reformers by engaging questions of gender, sexuality, race, embodiment, and the natural world. Feminist, womanist, queer, and ecological theologies challenged long-standing assumptions and opened new pathways for interpreting Christian faith in ways that honored human experience and promoted justice. Their influence created a broader and more inclusive theological tradition that continues to inform contemporary conversations about the role of Christianity in public life and the pursuit of social transformation.

Twenty-First-Century Progressive Christianity: Institutional Movements and Public Theology

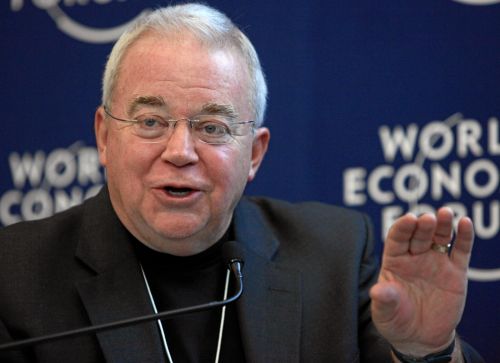

Progressive Christianity in the twenty-first century emerged within a context marked by political polarization, shifting religious demographics, and renewed attention to issues such as immigration, racial injustice, climate change, and LGBTQ rights. Many Christians sought alternatives to forms of Christianity that aligned themselves with nationalist or exclusionary political movements. This search led to a resurgence of traditions rooted in justice-oriented theology. Jim Wallis, founder of Sojourners, argued that Christian ethics required public engagement on behalf of marginalized communities and that faith could not be separated from social responsibility.22 His work offered a vocabulary for Christians who opposed the use of religion to justify discrimination or political authoritarianism.

Institutional movements expanded these concerns by creating networks committed to justice and inclusion. Red Letter Christians, for example, emphasized the ethical teachings attributed to Jesus in the Gospels and sought to distinguish their approach from more conservative expressions of American Christianity. Their focus on compassion, peacemaking, and social equity drew attention to the centrality of Jesus’s teachings about care for the poor and the vulnerable. Diana Butler Bass documented the ways in which many mainline Protestant communities adopted similar priorities, focusing on hospitality, community engagement, and democratic participation in congregational life.23 These developments reflected a broader realignment in American Christianity in which moral commitments took precedence over strict doctrinal boundaries.

Progressive Christian activism also responded to the rise of Christian nationalism, which scholars have identified as an influential political force in the United States. Many progressive Christians viewed this trend as a distortion of Christian ethics that conflated religious identity with national power. Public theologians argued that Christian nationalism contradicted biblical teachings about humility, justice, and the moral value of welcoming strangers. They drew upon earlier reform traditions, including the Social Gospel and liberation theology, to articulate an alternative vision of Christian public life. This critique gained visibility as progressive Christian leaders became more active in public debates about religious freedom, human rights, and democratic values.

Digital media helped shape contemporary expressions of progressive Christianity by allowing clergy, theologians, and laypeople to form online communities that extended beyond traditional denominational boundaries. These networks facilitated discussions about theology, social justice, and communal support. They also allowed progressive Christian voices to reach broader audiences and respond quickly to social and political developments. Online communities created new spaces for biblical interpretation, activism, and pastoral care, contributing to a dynamic and adaptive form of Christian engagement that resonated with younger generations. Pew Research Center surveys have shown that while religious affiliation in the United States has declined, interest in spiritual communities focused on justice and inclusion has increased among many adults.24

The theological concerns that shape contemporary progressive Christianity reflect the long trajectory of reform movements that preceded it. Its emphasis on equality, compassion, and public responsibility draws from the abolitionist tradition, the Social Gospel, civil rights activism, liberation theology, and the expansion of feminist, womanist, queer, and ecological theologies. Although twenty-first-century progressive Christianity does not form a single unified movement, it represents a constellation of communities committed to renewing Christian faith through ethical engagement and social transformation. These communities continue to reinterpret scripture and tradition in ways that honor human dignity and address the moral challenges of the modern world.

Conclusion

Progressive Christianity developed through a long trajectory of reform movements that challenged injustice and reshaped Christian tradition in response to the needs of changing societies. Its origins lie in the abolitionist and liberal Protestant movements of the nineteenth century, where Christians argued that moral responsibility required confronting systems of inequality. These early reformers laid the foundation for a theology that prioritized human dignity, ethical action, and critical engagement with scripture. Their work demonstrated that Christian faith could serve as a catalyst for social transformation and that theological inquiry could support efforts to confront the injustices embedded within political and cultural structures.25

The twentieth century expanded these commitments through the Social Gospel, the civil rights movement, and the emergence of liberation theologies in various global contexts. Reformers such as Walter Rauschenbusch, Martin Luther King Jr., James Cone, and Gustavo Gutiérrez linked Christian ethics to social reality by insisting that faith must respond to poverty, racism, and political oppression. Their ideas established a theological framework in which Christian praxis required engagement with structural injustices rather than solely personal morality. These developments reshaped Christian discourse and helped to define the responsibilities of communities seeking to embody the teachings of the Gospel within a diverse and unequal world.26

Later movements built upon these foundations by incorporating feminist, womanist, queer, and ecological perspectives that challenged inherited assumptions about gender, sexuality, embodiment, and humanity’s relationship to creation. These theologies broadened the concerns of progressive Christianity and encouraged a more inclusive and relational understanding of faith. Their influence extended into academic scholarship, congregational life, and public activism. They also expanded the interpretive resources available to Christians who sought to confront the social, cultural, and environmental crises of the late twentieth century.27 Together, these movements demonstrated the capacity of Christian tradition to evolve in response to the lived experiences of diverse communities.

Progressive Christianity in the twenty-first century continues to draw upon this historical legacy as it responds to new social and political realities. Its focus on justice, inclusion, and public responsibility reflects the enduring influence of earlier reform movements while adapting to contemporary challenges such as immigration, climate change, political extremism, and systemic inequality. Although progressive Christianity encompasses a wide range of theological commitments, it is unified by its emphasis on compassion, human dignity, and the ethical vision attributed to Jesus’s teachings. In this way, progressive Christianity represents both a continuation of longstanding reform traditions and an ongoing effort to reinterpret Christian faith in ways that address the moral issues of the modern world.28

Appendix

Footnotes

- Gary Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805–1900 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 33–61.

- David Friedrich Strauss, The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, trans. George Eliot (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1972), 5–18.

- Walter Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel (New York: Macmillan, 1917), 3–25.

- Theodore Dwight Weld, The Bible Against Slavery (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1837), 7–15.

- Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 118–128.

- Strauss, The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, 5–18.

- Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel, trans. J. Sutherland Black and Allan Menzies (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1885), 391–420.

- Gary Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology, 112–140.

- Washington Gladden, Applied Christianity: Moral Aspects of Social Questions (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1887), 3–15.

- Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 46–62.

- Federal Council of Churches, The Social Creed of the Churches (1908), in Max L. Stackhouse, Creeds, Societies, and Human Rights (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984), 105–106.

- Christopher H. Evans, The Social Gospel in American Religion: A History (New York: New York University Press, 2017), 132–158.

- Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail, in James M. Washington, ed., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1986), 289–302.

- James H. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (New York: Seabury Press, 1969), 27–44.

- Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation, trans. Sister Caridad Inda and John Eagleson (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1973), 11–32.

- Vatican Council II, Gaudium et Spes (1965), in Austin Flannery, ed., Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1981), 903–947.

- Rosemary Radford Ruether, Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology (Boston: Beacon Press, 1983), 11–29.

- Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins (New York: Crossroad, 1983), 25–46.

- Delores S. Williams, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1993), 1–18.

- Marcella Althaus-Reid, Indecent Theology: Theological Perversion in Sex, Gender and Politics (London: Routledge, 2000), 9–24.

- Sallie McFague, The Body of God: An Ecological Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 23–40.

- Jim Wallis, God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005), 25–45.

- Diana Butler Bass, Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening (New York: HarperOne, 2012), 97–118.

- Pew Research Center, “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace,” October 17, 2019.

- Gary Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology, 94–120.

- Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, 45–67; Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation, 35–54.

- Ruether, Sexism and God-Talk, 31–49; Althaus-Reid, Indecent Theology, 25–39.

- Bass, Christianity After Religion, 203–225.

Bibliography

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella. Indecent Theology: Theological Perversion in Sex, Gender and Politics. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Bass, Diana Butler. Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening. New York: HarperOne, 2012.

- Cone, James H. Black Theology and Black Power. New York: Seabury Press, 1969.

- Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

- Evans, Christopher H. The Social Gospel in American Religion: A History. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

- Federal Council of Churches. The Social Creed of the Churches (1908). In Max L. Stackhouse, Creeds, Societies, and Human Rights, 105–106. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984.

- Fiorenza, Elisabeth Schüssler. In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

- Flannery, Austin, ed. Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1981.

- Gladden, Washington. Applied Christianity: Moral Aspects of Social Questions. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1887.

- Gutiérrez, Gustavo. A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation. Translated by Sister Caridad Inda and John Eagleson. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1973.

- King, Martin Luther Jr. Letter from Birmingham Jail. In James M. Washington, ed., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., 289–302. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1986.

- McFague, Sallie. The Body of God: An Ecological Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993.

- Pew Research Center. “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” October 17, 2019.

- Rauschenbusch, Walter. A Theology for the Social Gospel. New York: Macmillan, 1917.

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford. Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology. Boston: Beacon Press, 1983.

- Strauss, David Friedrich. The Life of Jesus Critically Examined. Translated by George Eliot. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1972.

- Wallis, Jim. God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005.

- Weld, Theodore Dwight. The Bible Against Slavery. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1837.

- Wellhausen, Julius. Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel. Translated by J. Sutherland Black and Allan Menzies. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1885.

- Williams, Delores S. Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.