Public debate will always have a place in democratic life, but its structure makes it one of the least effective tools for changing minds.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Public debate is often treated as a pathway to persuasion, but decades of research show it rarely works that way. Philosophers, psychologists, and media scholars have repeatedly found that arguments in adversarial settings tend to harden views rather than shift them. A clash of claims does little to interrupt the deeper convictions that shape how people interpret information. The effect is even clearer in political arenas. Research on modern debate culture concludes that televised confrontations function more as performance than as genuine engagement, with participants focused on defending ground rather than reconsidering beliefs.

The problem extends beyond the stage. People process new facts through cognitive filters that protect their identity and worldview, often rejecting accurate information when it appears to threaten either. Neuroscience and psychology research further illustrates how the brain responds defensively when core beliefs are challenged, prioritizing emotional security over factual correction. Even data-driven work from The Alan Turing Institute demonstrates that exposure to facts alone does not produce immediate shifts in opinion, particularly on topics tied to group identity.

For these reasons, the assumption that debate leads to understanding rarely holds up in practice. The mechanisms shaping belief are slower, quieter, and more personal than the spectacle of argument suggests.

Why Arguments Fail: The Psychology Behind Resistance

Psychologists have long shown that people filter new information through cognitive patterns that protect their prior beliefs. Confirmation bias and motivated reasoning guide individuals toward evidence that aligns with what they already believe. When a claim threatens their worldview, the instinctive response is not to consider the new idea but to defend the old one.

Neuroscientists have documented the biological side of this resistance. The brain registers challenges to core beliefs as a potential threat. This activates emotional regions rather than the networks involved in analytical evaluation, making people more likely to reject information that feels personally destabilizing, even if it is accurate.

Data-centered research supports these psychological and neurological findings. Factual corrections rarely produce immediate changes in opinion. In some cases, attempts to correct misinformation can strengthen existing beliefs when individuals feel socially or emotionally pressured to abandon their stance.

Taken together, these insights reveal that resistance to new information is not caused by ignorance or a lack of evidence. It is the result of deep psychological habits and identity commitments that make direct confrontation one of the least effective ways to change a person’s mind.

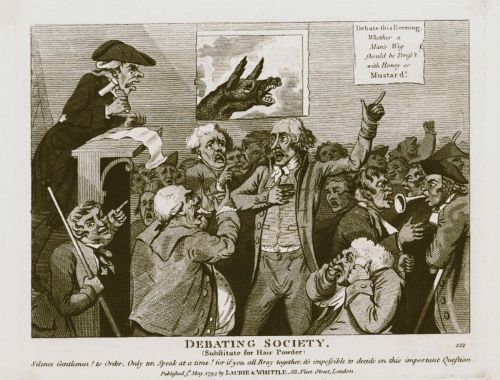

The Performance Problem: Debate as Spectacle, Not Learning

Public debate often rewards performance more than reflection. Modern debates function as staged events designed to reinforce loyalty rather than prompt genuine reconsideration. Viewers interpret arguments through the lens of their preferred identities, and participants focus on defending their position rather than examining its weaknesses. In this environment, persuasion becomes secondary to the appearance of strength.

Studies on political communication show that this dynamic is not accidental. Structured disagreements tend to change emotional responses, not underlying beliefs. When participants feel the pressure to win, they become more concerned with signaling confidence than understanding the opposing side. The discussion becomes a contest in which conceding a point feels like losing ground, even when new facts are presented.

Media scholars point out that format also shapes outcomes. Televised or public debates encourage quick replies, simplified claims, and confident sound bites. These constraints make thoughtful engagement difficult. Reasoning under competitive conditions rarely leads to deeper insight. Instead, it reinforces the belief that the goal of argument is to prevail, not to learn.

The result is a communication environment that discourages the very conditions needed for belief change. Reflection, uncertainty, and slow integration of facts are replaced by pressure, speed, and social signaling. Debate becomes a performance in which participants must defend their stance, making it one of the least effective tools for fostering understanding.

Where Minds Actually Change: Personal Experience and Quiet Exposure

Research on belief formation shows that people change their minds gradually, often long after they first encounter new information. Individuals typically resist facts in the moment, but may integrate them later when they feel less pressure to defend their existing views. This delayed processing reflects the difference between public confrontation and private reflection.

Personal experience is one of the strongest forces behind belief change. Studies in psychology and social cognition show that when new information aligns with real-world experiences, people become more willing to reconsider their assumptions. Emotional safety plays a significant role in this process. Individuals are more receptive to new evidence when they do not feel that their identity or group loyalty is at stake.

Social context also shapes openness to new ideas. Belief shifts often occur within networks of trust rather than in confrontational exchanges. When information comes from sources perceived as credible, respectful, or familiar, people are more likely to consider it seriously. This trust-based model of persuasion contrasts sharply with the combative style of public debate.

Repeated exposure to accurate information contributes to gradual change as well. Data-driven research shows that people tend to update their beliefs incrementally over time, especially when they encounter the same factual material in low-pressure settings. This pattern reflects how the brain consolidates new understanding without the emotional burden of defending prior views.

These findings reveal a consistent theme: meaningful belief change happens quietly. It emerges from reflection, experience, trusted relationships, and steady exposure to reliable information. Unlike debate, which encourages defensiveness, these environments give people the space to rethink their assumptions on their own terms.

The Practical Alternative: Provide Information, Skip the Argument

If debate tends to entrench beliefs, then the more productive approach is to make reliable information accessible without demanding immediate agreement. People often update their views slowly through repeated encounters with accurate facts. This process works best when individuals do not feel pressured to defend their prior position, which allows new information to be absorbed at a manageable pace.

Psychological studies emphasize the importance of emotional safety in this process. Individuals are more open to reconsidering their beliefs when the information arrives in contexts that reduce defensiveness. Communication that avoids confrontation creates the conditions in which people feel free to think rather than react.

Philosophical commentary reinforces the idea that argument is only one part of a much larger landscape of persuasion. Reasoning alone is rarely sufficient to shift deeply held commitments. Instead, understanding grows when people have time to reflect and compare new ideas with their lived experiences. That reflective space is almost impossible to create in adversarial exchanges.

Journalistic analysis adds a final layer to the picture. People often rethink their views in private, away from the social pressure of “winning” an argument. When information is offered calmly and consistently, without confrontation, it becomes a resource rather than a challenge. This makes quiet, factual communication one of the most effective tools for long-term belief change.

Conclusion

Public debate will always have a place in democratic life, but its structure makes it one of the least effective tools for changing minds. Individuals tend to interpret arguments through the lens of identity, pressure, and performance. These conditions encourage people to hold their ground instead of examining new information. The result is a dynamic in which debate rewards certainty rather than thoughtfulness.

The research is clearer about what works. People reconsider their beliefs gradually, through private reflection, personal experience, and steady exposure to accurate information. Studies show that belief change is a process shaped by emotional safety and repetition, not confrontation. When information arrives without pressure, individuals have the freedom to rethink their assumptions on their own terms.

This quieter model of persuasion asks more patience of us, but it produces deeper results. Instead of entering unwinnable arguments, the more effective approach is to make factual, grounded information available and let people encounter it when they are ready. Minds shift when the noise quiets down, not when the shouting grows louder.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.