Silence in medieval monasticism emerged as a dynamic practice shaped by theology, discipline, and the practical demands of communal life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Silence played a central role in the spiritual imagination of medieval monasticism, shaping the discipline, identity, and daily rhythm of communities across Western Europe. The practice was not uniform, nor was it absolute. Instead it formed part of a carefully regulated system of conduct in which speech was controlled rather than abolished. The Rule of St. Benedict, written in the sixth century and foundational for most medieval monastic orders, highlighted restraint in speech as a virtue that fostered humility and guarded against frivolity.1 Later customs elaborated these guidelines but retained the principle that silence was a means of cultivating interior stillness rather than a literal vow of perpetual muteness.

As monastic communities grew in size and complexity, silence required practical accommodations. Monks needed ways to communicate essential information during extended periods when speech was restricted, and by the tenth century many Benedictine and reformed houses had developed structured systems of hand signs to meet this need.2 These gestures did not replace speech entirely. Instead they offered a means of supporting the community’s discipline by allowing necessary communication while preserving the atmosphere of quiet reflection that monastic writers consistently regarded as integral to a devout life. The survival of sign lists in Cluniac, Fleury, and Hirsau customs demonstrates how widespread and formalized these practices became.

Modern scholarship has emphasized that medieval monastic silence operated within a broader framework of spiritual and psychological formation. Writers such as Jean Leclercq and Marilyn Dunn have shown that silence functioned as an instrument for shaping character, focusing attention, and creating a communal environment oriented toward contemplation.3 These studies highlight the breadth of the tradition by examining how monastic authors interpreted silence as a discipline that combined inward reflection with outward restraint.

The ideal of absolute silence, often imagined in modern portrayals of monastic life, does not appear in the historical record. Even in the most austere orders, including the Carthusians, periods of speech were permitted for practical or communal purposes.4 What emerges instead is a spectrum of practices, each grounded in a consistent understanding of silence as a structured, purposeful mode of living that supported prayer, stability, and communal harmony. Examining these traditions across different orders illuminates the variety of ways medieval monastic communities balanced regulation and flexibility in their pursuit of spiritual discipline.

The Rule of St. Benedict and Early Medieval Ideals of Silence

The Rule of St. Benedict shaped the foundational logic of silence in Western monasticism, presenting measured restraint in speech as a spiritual discipline central to the cultivation of humility. Benedict did not require perpetual muteness. Instead he urged monks to avoid idle talk and to cultivate a disposition in which words were used sparingly and with deliberation.5 These instructions reflected a belief that silence protected the community from distraction and preserved the inner concentration necessary for prayer and study. Benedict’s discussion of silence appears in several chapters of the Rule, indicating the degree to which it permeated both his understanding of personal discipline and his vision for communal stability.

Benedictine silence primarily took the form of structured regulation. Chapter 6 instructs monks to speak only when necessary and chapter 42 establishes the “Great Silence,” a period after Compline when conversation was prohibited until the following morning.6 This pattern created daily rhythms in which silence and speech functioned together rather than in opposition. The intention was not to suppress communication but to moderate it, ensuring that conversation occurred at appropriate times. Early medieval commentaries on the Rule, including those preserved in monastic collections, show that these practices were understood as tools of spiritual formation rather than rigid prohibitions that eliminated speech entirely.

The Rule’s emphasis on interior discipline shaped how early medieval communities implemented silence. Early Benedictines interpreted silence as a means of cultivating vigilance over thought and emotion.7 Speech was regarded as a potential source of conflict, pride, or distraction, and silence provided a form of restraint that encouraged inward watchfulness. This approach appears in early Benedictine customs such as the Concordia Regularis, which expanded upon Benedict’s framework to regulate conversation in refectories, dormitories, and cloisters. These texts reveal continuity with Benedict’s intention, even as monastic life developed more complex forms of communal organization.

The Rule also offered practical mechanisms for maintaining order within the monastery. Silence supported liturgical clarity, minimized disruption during work, and reinforced the hierarchy of obedience.8 Monks were expected to respond to superiors with few words, and conversation among peers was regulated to ensure that discipline remained consistent. These procedures enabled large communities, sometimes housing several hundred monks, to function smoothly without constant verbal direction. The emphasis on moderation reveals that silence served administrative as well as spiritual purposes, contributing to the cohesion and routine of monastic life.

By the tenth century, Benedictine silence had influenced a wide network of monasteries across Western Europe. The Rule’s measured approach shaped how later communities adapted silence to new contexts, including the development of sign systems and the more rigorous practices of reformed houses.9 The influence of Benedict’s framework remained evident even where customs became stricter, since the underlying principle remained constant: silence was a disciplined commitment to attentiveness grounded in the daily structure of monastic life. Understanding these early foundations is essential for interpreting the more elaborate practices that emerged in later centuries.

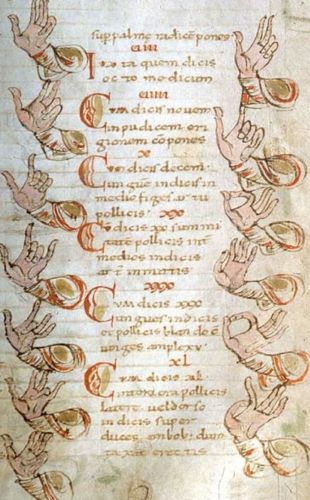

The Development of Monastic Sign Systems

As medieval monastic communities adopted increasingly regulated forms of silence, they developed systematic methods of communication that allowed daily tasks to continue without disrupting the atmosphere of quiet. These systems took the form of structured hand signs that enabled monks to express basic needs, identify objects, request tools, or signal liturgical actions.10 The earliest references to such signs appear in Benedictine contexts, where practical gestures supplemented the periods of restricted speech established by the Rule. Although the Rule of St. Benedict does not provide a formal sign list, its emphasis on restraint created the conditions that encouraged monks to adopt nonverbal forms of communication during times when speaking was limited.

By the tenth century, monastic sign systems had become significantly more elaborate, particularly in reformed Benedictine houses. The Cluniac Consuetudines, which detail the customs governing liturgy, work, and monastic discipline, include some of the earliest surviving sign lists used for communication during meals and other periods of silence.11 These gestures created a regulated vocabulary that allowed monks to communicate efficiently without undermining the quiet expected in the cloister and refectory. Similar developments occurred at Fleury and Hirsau, where customs emphasized the gestures appropriate for identifying books, tools, foods, and personal needs. The survival of these lists in manuscript form confirms their widespread use and importance.

The intellectual and cultural significance of these sign systems has attracted scholarly attention. Studies by researchers have examined the semiotic structure of monastic signs, emphasizing that they formed a functional language shaped by the community’s needs.12 These systems were not intended to convey abstract ideas or theological concepts. Instead they served practical purposes, enabling monks to maintain discipline without interrupting the quiet required for contemplation. Their structure varied from house to house, reflecting local customs and the degree of silence observed during daily routines.

Monastic sign languages illuminate the balance medieval communities sought between regulation and practicality. Silence was a spiritual and disciplinary ideal, but daily life required communication, especially in large monasteries where dozens or hundreds of monks lived and worked together.13 Sign systems provided a means of respecting the Rule’s intention without compromising the monastery’s ability to function. Their development demonstrates how monastic communities adapted ancient ideals to changing circumstances, creating tools that preserved the contemplative environment while supporting communal life.

Cluniac Reform and the Intensification of Silence Practices

The tenth and eleventh centuries witnessed the rise of the Cluniac reform movement, which reshaped Benedictine monastic practice across Western Europe and deepened the regulation of silence within monastic communities. Cluniac houses interpreted the Rule of St. Benedict with a strong emphasis on liturgical order and communal discipline, extending periods of silence and formalizing the contexts in which monks could speak.14 The monastic day became more tightly structured around the Divine Office, and silence served as a framework that reinforced the dignity and solemnity of the liturgy. This approach reflected the Cluniac conviction that ordered communal worship was the highest expression of monastic life.

Silence in Cluniac monasteries was more rigorously enforced than in earlier Benedictine settings. The Cluniac Consuetudines, preserved in several manuscript traditions, outline detailed protocols governing conversation in the cloister, refectory, dormitory, and workspaces.15 Speech during meals was prohibited except for the reader who recited Scripture or hagiography, and even outside the refectory monks were encouraged to use signs for ordinary communication. These customs framed silence as an extension of the monastic pursuit of purity and attentiveness, reinforcing the idea that controlled speech formed part of the spiritual discipline required for communal harmony.

The scale of Cluny contributed to these developments. At its height, Cluny housed a large monastic population, and the complexity of managing such a community required careful regulation of movement, communication, and routine.16 Silence helped reduce confusion and ensured that the community functioned smoothly despite its size. The Cluniac liturgical cycle, which expanded far beyond that of earlier Benedictine practice, demanded a quiet environment where the focus remained on prayer rather than conversation. This relationship between silence and liturgical order distinguishes the Cluniac approach from the more flexible practices found in smaller monastic houses.

Scholars have noted that the Cluniac reform also shaped attitudes toward silence outside the monastic enclosure. The emphasis on order and solemnity influenced how monks interacted with guests, conversed with officials, and participated in charitable or administrative tasks.17 While speech was not entirely forbidden in these contexts, Cluniac customs encouraged restraint and moderation. Silence thus became a marker of monastic identity, distinguishing monks from the secular world even in moments when engagement with external society was necessary. The discipline created a distinctive atmosphere that contemporaries associated with Cluny’s reputation for sanctity and refinement.

The Cluniac model influenced many Benedictine houses across Europe, and its customs formed the basis for reforms in regions such as Hirsau and Fleury.18 These communities adopted Cluniac-style silence as part of a broader commitment to reviving monastic discipline and strengthening the spiritual character of communal life. The wide diffusion of Cluniac practices highlights their durability and the appeal of a structured approach to silence that balanced spiritual aspiration with practical administration. Understanding these developments is essential for interpreting the more austere reforms that emerged in later monastic traditions, particularly among the Cistercians.

Cistercian Interpretations of Silence and the Pursuit of Inner Stillness

The Cistercian movement, founded at the end of the eleventh century, sought to return monastic life to what its founders regarded as the genuine spirit of the Rule of St. Benedict. Silence played a central role in this reform, not as an absolute prohibition on speech but as an inward discipline connected to humility, interior quiet, and the renunciation of unnecessary distraction.19 The early Cistercians believed that excessive conversation undermined the contemplative focus of the monk and interfered with the simplicity and austerity that lay at the heart of their vision. Silence therefore became one of the clearest markers distinguishing Cistercian identity from the more elaborate observances of Cluniac monasteries.

The Carta Caritatis, the foundational document of the order, set the tone by emphasizing uniformity of observance across all Cistercian houses. Although it did not prescribe a detailed silence code, it reinforced Benedictine restraint as a condition of communal harmony.20 Early Cistercian statutes elaborated these principles by establishing quiet zones within the monastery, formalizing the hours in which speech was permitted, and insisting on decorum appropriate to the contemplative life. These regulations aligned with the order’s broader commitment to simplicity, manual labor, and a reduced liturgical cycle. Silence became one of the mechanisms through which the order distanced itself from the complexity associated with Cluniac observance.

Writings associated with the early Cistercians expanded the spiritual interpretation of silence. Bernard of Clairvaux, although not an author of silence regulations per se, repeatedly described restraint in speech as a sign of humility and a necessary condition for spiritual clarity.21 His influence within the order shaped how silence was linked to ascetic discipline and interior purification. In this context, silence was not merely a practical rule but a mode of cultivating the monastic virtues that defined the Cistercian life. Bernard’s emphasis on the heart and mind as spaces requiring protection from distraction offered an interpretive lens through which later Cistercians understood the value of quiet.

The discipline of silence also affected daily work in Cistercian communities. Unlike the Cluniacs, whose liturgical commitments required extensive coordination and communication, the Cistercians placed a strong emphasis on manual labor performed with minimal conversation.22 Work in the fields, gardens, workshops, and granges was carried out in an atmosphere intended to reinforce inward recollection. Speech was not forbidden, but when necessary it was kept brief and functional. This created a rhythm in which physical labor supported contemplation by minimizing stimulation and promoting attention to the spiritual meaning of work.

Cistercian houses likewise developed sign systems, although generally less elaborate than those found in Cluniac monasteries. Manuscripts containing monastic signs survive from Cistercian contexts and reveal a vocabulary geared toward the tasks of agricultural life, liturgical participation, and daily routine.23 These signs supplemented periods of regulated silence and allowed communities to maintain order without interrupting the stillness that characterized Cistercian practice. The use of signs underscored the balance between discipline and practicality that marked the order’s approach to silence.

Modern scholarship has emphasized that Cistercian silence represented a distinctive synthesis of spiritual intention and institutional structure. Studies highlight the connection between the order’s emphasis on inner transformation and its external practices of restraint.24 Silence was one component of a larger system oriented toward simplicity, humility, and obedience. Its disciplined character shaped the identity of the Cistercians and contributed to their reputation as a movement revitalizing monastic ideals. Understanding their approach provides essential context for interpreting the more solitary and rigorous silence practices that emerged among the Carthusians.

The Carthusians and the Ideal of Solitary Silence

The Carthusian order, founded in the late eleventh century by Bruno of Cologne, developed the most intensive form of regulated silence in Western monasticism. Their way of life combined eremitic solitude with communal structure, and silence supported both dimensions of their identity.25 Carthusians lived in individual cells arranged around a great cloister, where much of their time was dedicated to prayer, reading, and manual work performed alone. While the order did not describe its practice as a perpetual vow of silence, the daily routines created long intervals during which monks refrained from speaking and interacted with the community primarily through liturgical participation and periodic meetings.

Carthusian statutes codified silence in ways distinct from the customs of Benedictine, Cluniac, or Cistercian houses. Early texts attributed to Guigo I, often referred to collectively as the Consuetudines, describe periods when speech was permitted, including weekly chapter meetings and essential discussions related to the administration of the house.26 These rules emphasize restraint rather than absolute prohibition. Silence functioned as a means of supporting the monk’s solitary vocation, protecting the contemplative environment necessary for sustained interior prayer. The careful balance between solitude and communal obligation shaped a discipline uniquely suited to Carthusian life.

The order’s architectural design reinforced its silence practices. Individual hermitages connected to the cloister allowed monks to live in near-solitary conditions while remaining part of a community governed by shared observance.27 Each cell included a small garden, workroom, and oratory, creating a microcosm in which the monk lived largely without verbal interaction. The refectory was used infrequently, since monks generally ate alone in their cells, further reducing occasions for speech. This arrangement distinguished Carthusian silence from that of other orders, not through stricter rules but through an environment intentionally shaped to minimize verbal communication.

Despite this strong emphasis on solitude, the Carthusians acknowledged the necessity of certain forms of communal communication. Statutes required novices to receive instruction, which involved spoken teaching, and permitted monks to consult with priors or spiritual directors when needed.28 The order also preserved times for limited conversation during recreation, though far more rarely than in Benedictine or Cistercian houses. These allowances demonstrate that silence within the Carthusian tradition remained regulated rather than absolute. It was designed to harmonize with a life centered on contemplative withdrawal rather than to impose muteness as an unbroken rule.

Modern studies have highlighted the continuity between Carthusian silence and broader monastic traditions. Scholars have examined the ways in which the Carthusians extended earlier ideals of restraint into a more solitary context.29 Their practice reveals a nuanced understanding of silence as both a personal and communal discipline, rooted in stability, humility, and attentiveness. Carthusian silence thus represents the culmination of medieval monastic reflections on speech, illustrating how long-standing traditions were adapted to serve an increasingly contemplative form of religious life.

Silence as Spiritual Technology: Theological and Psychological Dimensions

Silence in medieval monasticism functioned as a deliberate spiritual discipline shaped by long-standing theological reflection. Monastic writers regarded the restraint of speech not as an end in itself but as a means of cultivating attentiveness toward God and maintaining interior clarity. Monastic spirituality centered on a unified life of prayer in which silence played a supporting role, enabling monks to withdraw from distractions that hindered contemplation.30 This approach reflects the conviction that silence fostered the conditions necessary for sustained meditation on Scripture and the pursuit of humility, two core elements of the monastic vocation.

Medieval monastic authors frequently linked silence to the regulation of thoughts and emotions. This connection appears in early Benedictine commentaries and continued throughout the Middle Ages in texts that treated speech as a potential source of pride, conflict, or spiritual imbalance.31 Silence served as a discipline that created space for reflection and for the careful management of inward impulses. Scholars such as Marilyn Dunn have analyzed how this approach forms part of a broader monastic psychology in which self-control was cultivated through external practices that gradually shaped interior habits.32 Monastic silence therefore belonged to a larger system of training that included fasting, obedience, and daily routine.

The communal dimension of silence was equally significant. Medieval monasteries conceived of silence as a practice that preserved harmony within the cloister by preventing unnecessary disputes and reducing the likelihood of interpersonal tension.33 Customaries emphasized that restraint in speech encouraged mutual respect and supported the stability essential for coexisting within a disciplined community. Silence reinforced the idea that the monastery was a space set apart, marked by a rhythm of life in which speech occurred purposefully rather than spontaneously. This understanding helps explain why so many orders sought not to eliminate conversation but to situate it within designated times that supported rather than disrupted communal order.

Silence also shaped the monastic experience of liturgy. The Divine Office required attentiveness, and silence before and after liturgical celebrations helped monks prepare their thoughts and maintain focus.34 Monastic writers commented that frequent or careless conversation could diminish the reverence owed to the communal prayer of the monastery. This perspective became particularly prominent during the Cluniac and Cistercian periods, when liturgical life expanded in complexity or assumed new forms of contemplative emphasis. In both settings silence functioned as a means of facilitating transitions between work, prayer, reading, and meditation without fracturing the unity of the monastic day.

By the high Middle Ages, silence had become an essential marker of monastic identity across a range of orders. Although expressed differently in Benedictine, Cluniac, Cistercian, and Carthusian contexts, the spiritual logic behind silence remained consistent.35 It represented a disciplined way of inhabiting time, of guarding speech, and of cultivating a stable environment conducive to contemplation. Modern historians have emphasized that these practices reflected an integrated vision of religious life in which external and internal disciplines reinforced one another. Silence thus functioned not as a rigid prohibition but as a carefully calibrated spiritual technology that shaped the intellectual, emotional, and communal dimensions of monastic existence.

Misconceptions and the Myth of the Absolute Vow of Silence

Modern portrayals of medieval monasticism often imagine monks living under perpetual vows of silence, but the historical record reveals a far more nuanced reality. Silence in Benedictine, Cluniac, Cistercian, and Carthusian settings took the form of regulated periods during which speech was limited, not eliminated.36 Medieval rules and customs consistently outlined times when speech was permitted for work, instruction, confession, and administration. Fictional depictions of unbroken muteness overlook the structured rhythm of silence and conversation that shaped daily life in monastic communities, where regulation rather than prohibition was the guiding principle.

These misconceptions likely arise from the austere practices observed in some reformed orders, especially the Carthusians, whose emphasis on solitary contemplation has been interpreted as evidence of continuous silence. Yet Carthusian statutes clearly distinguished between ordinary restraints on speech and moments when conversation was necessary for spiritual, administrative, or communal purposes.37 The same pattern appears in Cistercian and Cluniac customaries, which record rules governing when monks could speak, with specific hours designated for communal meetings or essential communication. The presence of detailed rules for permitted speech contradicts the idea that any order enforced complete and permanent silence.

Another factor contributing to the myth of absolute silence is the survival of monastic sign lists, which can appear to modern readers as proof that monks avoided speech entirely. In reality, these signs supplemented speech only during periods of restricted communication, such as meals or the Great Silence at night.38 The development of these systems demonstrates that medieval monastic communities recognized the practical limits of silence and adapted their customs to maintain discipline while enabling the tasks of daily life. Sign languages were tools of efficiency, not evidence of perpetual muteness.

The persistence of these misunderstandings highlights the contrast between modern imaginative constructions of monastic life and the more complex historical traditions preserved in rules, statutes, and customaries. Scholars emphasize that silence served as a spiritual discipline integrated into broader patterns of prayer, work, and study rather than as an isolated or absolute requirement.39 Recognizing this distinction provides clarity about the intentions behind monastic silence and allows for a more accurate understanding of how medieval communities regulated communication within the framework of their spiritual ideals.

Conclusion

Silence in medieval monasticism emerged as a dynamic practice shaped by theology, discipline, and the practical demands of communal life. It evolved from the foundational principles laid out in the Rule of St. Benedict, which emphasized the spiritual value of measured speech and the importance of maintaining an atmosphere conducive to contemplation.40 Over time, these ideals were interpreted and expanded in various monastic reforms, each adapting the framework of regulated silence to its own spiritual goals and institutional structures. The result was a diverse landscape in which silence supported prayer, shaped community identity, and structured the rhythms of daily life.

Different monastic orders contributed distinctive interpretations to this shared tradition. Cluniacs developed highly regulated customs that extended periods of silence as part of their elaborate liturgical discipline. Cistercians adapted silence to their pursuit of simplicity and interior recollection, integrating it into a program of manual labor, humility, and communal harmony. Carthusians carried the ideal further by embedding silence into a solitary architectural environment that minimized conversation while still acknowledging the necessity of regulated speech.41 The diversity of these practices demonstrates that silence functioned as a flexible discipline, deeply rooted in shared ideals but expressed differently according to the needs and aspirations of each community.

The enduring significance of monastic silence lies in its integration of the spiritual, psychological, and communal dimensions of medieval religious life. Modern scholarship highlights that silence was not merely an absence of words but a deliberate mode of being that shaped attention, fostered stability, and supported the contemplative vocation of the monk.42 Understanding these practices corrects modern misconceptions about perpetual muteness and reveals the sophistication with which medieval monastic communities regulated communication. Silence, far from being a static or rigid requirement, served as a disciplined framework that enabled monks to inhabit their world with clarity, purpose, and sustained spiritual focus.

Appendix

Footnotes

- The Rule of St. Benedict, ed. and trans. Timothy Fry, O.S.B. (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1981), chapters 6 and 7.

- Consuetudines Farfenses, in Le istituzioni monastiche italiane, ed. and trans. Girolamo Arnaldi (Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano, 1969); see also C. H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism (London: Longman, 1984), 112–115.

- Jean Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God (New York: Fordham University Press, 1960); Marilyn Dunn, The Emergence of Monasticism (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000).

- Tim Peeters, When Silence Speaks: The Spiritual Way of the Carthusian Order, (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2015), 44–60.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 6.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 42.

- Adalbert de Vogüé, La Règle de saint Benoît (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1972–1977), vol. 1.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 67–72.

- Concordia Regularis, ed. Thomas Symons (London: Thomas Nelson, 1953), introduction and commentary.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 6.

- Consuetudines Farfenses,; Consuetudines Cluniacenses, in Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, vol. 8 (Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1877).

- Umberto Eco, From the Tree to the Labyrinth (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 50–67; Scott G. Bruce, Silence and Sign Language in Medieval Monasticism: The Cluniac Tradition, c.900–1200, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 48-50.

- Dunn, The Emergence of Monasticism, 122–132.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 106–114.

- Consuetudines Cluniacenses, 48–62.

- Ibid., 63–78.

- Hermann of Reichenau, De institutione clericorum; Consuetudines Hirsaugienses, ed. and trans. in J. M. Canivez, Statuta Ordinis Cisterciensis (Louvain: Bureaux du Recueil, 1933), introduction.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 138–147.

- Carta Caritatis, in J. M. Canivez, Statuta Ordinis Cisterciensis (Louvain: Bureaux du Recueil, 1933), 1–15.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons for the Seasons and Principal Feasts, trans. Cistercian Fathers series (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, various volumes).

- Giles Constable, The Reformation of the Twelfth Century, 164–180.

- David Bell, What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1995), appendix on monastic signs.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 43–64.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 156–162.

- Guigo I, Consuetudines Cartusiae, ed. J.-P. Anché (Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 1970).

- Denis Martin, Fifteenth-Century Carthusian Reform: The World of Nicholas Kempf. (London: Brill, 1992), 27–45.

- Peeters, When Silence Speaks, 61–76.

- Martin, Fifteenth-Century Carthusian Reform, 68–82.

- Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 57–73.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 6.

- Dunn, The Emergence of Monasticism, 112–135.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 67–72.

- Constable, The Reformation of the Twelfth Century, 84–100.

- Bynum, Jesus as Mother, 43–64.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapters 6 and 42.

- Elder, The Charterhouse of Parma, 61–76.

- Consuetudines Cluniacenses, vol. 8.

- Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 106–115.

- Constable, The Reformation of the Twelfth Century, 84–100.

- The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 6.

- Martin, Fifteenth-Century Carthusian Reform, 27–45.

- Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 57–73.

Bibliography

- Arnaldi, Girolamo, ed. Le istituzioni monastiche italiane: Consuetudines Farfenses. Rome: Istituto Storico Italiano, 1969.

- Bell, David. What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1995.

- Bernard of Clairvaux. Sermons for the Seasons and Principal Feasts. Translated in the Cistercian Fathers series. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, various volumes.

- Bruce, Scott G. Silence and Sign Language in Medieval Monasticism: The Cluniac Tradition, c.900–1200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

- Canivez, J. M., ed. Statuta Ordinis Cisterciensis. Louvain: Bureaux du Recueil, 1933.

- Cluny. Consuetudines Cluniacenses. In Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, vol. 8. Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1877.

- Constable, Giles. The Reformation of the Twelfth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Dunn, Marilyn. The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

- Eco, Umberto. From the Tree to the Labyrinth: Historical Studies on the Sign and the Interpretation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Fry, Timothy, O.S.B., ed. The Rule of St. Benedict. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1981.

- Guigo I. Consuetudines Cartusiae. Edited by J.-P. Anché. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 1970.

- Hermann of Reichenau. De institutione clericorum. In J. M. Canivez, Statuta Ordinis Cisterciensis. Louvain: Bureaux du Recueil, 1933.

- Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. London: Longman, 1984.

- Leclercq, Jean. The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture. New York: Fordham University Press, 1960.

- Martin, Denis. Fifteenth-Century Carthusian Reform: The World of Nicholas Kempf. London: Brill, 1992.

- Peeters, Tim. When Silence Speaks: The Spiritual Way of the Carthusian Order. London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2015.

- Symons, Thomas, ed. Concordia Regularis. London: Thomas Nelson, 1953.

- Vogüé, Adalbert de. La Règle de saint Benoît. 3 vols. Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1972–1977.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.