Robert G. Ingersoll’s career reveals the centrality of public oratory to the intellectual and political life of the late nineteenth century.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Ingersoll and the Cultural Terrain of the Gilded Age

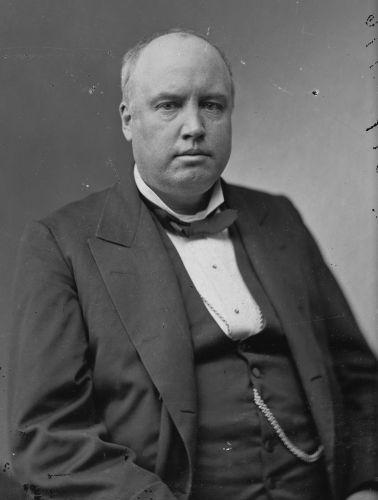

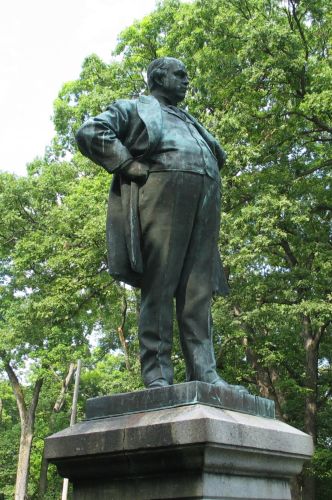

Robert G. Ingersoll emerged as one of the most recognizable public figures in the United States during the final decades of the nineteenth century. His reputation rested on the force of his oratory and the clarity of his freethought philosophy, both of which he displayed before enormous audiences on the national lecture circuit. Newspapers from New York to Chicago recorded the crowds that gathered to hear him speak on subjects ranging from biblical criticism to political reform.1 His rise occurred in a cultural moment marked by conflict over science, morality, and the authority of Protestant institutions, making his prominence a measure of the intellectual tensions that shaped public life in the Gilded Age.

Ingersoll’s career reflected the rapid social and political transformations of the post–Civil War era. The expansion of mass printing, the growth of lecture-hall culture, and the increasing visibility of scientific discourse created new opportunities for figures who challenged older forms of religious authority. His public persona blended legal training, military service, and a powerful rhetorical style that resonated with audiences navigating questions of belief and identity in a changing nation.2 The popularity of his addresses, many of which circulated through pamphlets, newspapers, and authorized editions of his collected works, demonstrated the extent to which freethought had become part of mainstream discussion rather than a fringe intellectual pursuit.3

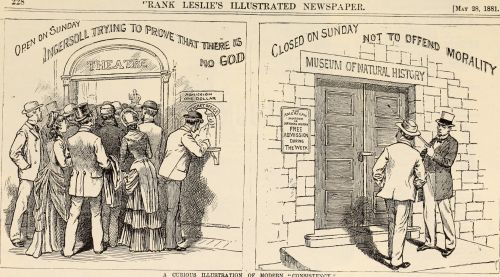

In this context, Ingersoll became both a celebrated and contested figure. Admirers saw him as a champion of reason, liberty, and secular ethics, while critics regarded him as a threat to the moral foundations of American society. Clerical responses to his lectures appeared regularly in the press, reflecting broader anxieties about scientific authority, biblical interpretation, and the place of religion in public life.4 The debate surrounding Ingersoll’s ideas was not confined to intellectual circles but took shape within a broader culture increasingly defined by mass participation, political realignment, and expanding public discourse.

What follows examines Ingersoll’s career within these cultural and political contexts. By analyzing his rhetorical strategies, public influence, political commitments, and the reception of his ideas, the essay aims to assess the historical significance of the figure widely known as “The Great Agnostic.” The following sections trace his development as a speaker, the content of his freethought philosophy, his relationship to the politics of the Gilded Age, and the reasons his once widespread fame receded in the twentieth century.5 The goal is to situate Ingersoll not simply as a critic of religion but as a figure whose work illuminates key transformations in American public culture.

Early Life, Civil War Service, and the Shaping of a Public Voice

Ingersoll’s early years in Illinois shaped both the content and style of his later public work. Born in 1833 to a family deeply involved in abolitionist activism, he grew up in communities where debates over slavery, religious authority, and political reform formed part of daily life. His father, Reverend John Ingersoll, frequently faced opposition from congregants because of his antislavery views, creating an environment in which young Robert witnessed the social costs of principled dissent.6 This experience impressed upon him the significance of public conviction and the consequences of challenging prevailing moral norms.

After studying law in his early twenties, Ingersoll developed a legal practice that placed him in courtrooms across Illinois. His work required skills in persuasion, improvisation, and clarity of expression, all of which would later define his reputation on the national lecture circuit. Court records from the 1850s show his involvement in cases concerning property, criminal proceedings, and contract law.7 These early professional experiences introduced him to the rhetorical demands of presenting arguments to diverse audiences, shaping his capacity to move between legal reasoning and broader moral commentary. The courtroom became the first stage on which he refined the techniques that would later attract thousands.

Ingersoll’s military service during the Civil War further contributed to his emerging public identity. He served as colonel of the 11th Illinois Cavalry, a position that required both administrative skill and the ability to command troops drawn from rural and small-town communities. Military documents record his participation in campaigns in Tennessee and Mississippi, though his service was cut short after he was captured near Lexington, Tennessee, and later released on parole.8 These experiences exposed him to the political stakes of the conflict and to the sacrifices demanded of ordinary soldiers, shaping his commitment to a vision of the Union rooted in liberty and citizenship.

Following the war, Ingersoll returned to Illinois and resumed his legal and political activities. His speeches supporting Reconstruction, veterans’ rights, and civil service reform attracted growing attention. One of his earliest notable addresses, delivered in Peoria in 1867, appeared in several Midwestern newspapers, reflecting the expansion of his public profile.9 These postwar speeches reveal a figure increasingly comfortable addressing large audiences and engaging with national questions, a development that foreshadowed his later emergence as the leading orator of American freethought.

By the early 1870s, Ingersoll had established himself as a political speaker capable of drawing significant crowds at Republican gatherings. His involvement in campaigns for figures such as James G. Blaine further increased his visibility, even as his open agnosticism limited his prospects for formal political office.10 The combination of legal expertise, wartime service, and early public advocacy provided the foundation for his transformation into a national lecturer. These formative experiences shaped not only the content of his later freethought addresses but also the rhetorical strategies through which he presented reason, liberty, and skepticism to audiences across the country.

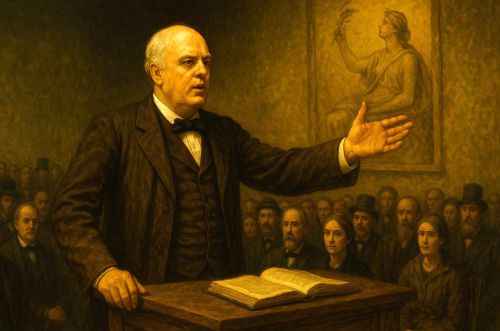

Oratory, Theater, and the Lecture Circuit: Building a National Audience

The rise of the commercial lecture circuit after the Civil War created a uniquely fertile environment for Ingersoll’s public career. Large urban theaters and smaller regional halls offered platforms for speakers who could attract paying audiences, and Ingersoll quickly became one of the most sought-after performers. Newspaper notices from Boston, New York, Chicago, and St. Louis document crowds that filled venues to capacity to hear him speak on religion, science, and politics.11 Unlike many lecturers who relied heavily on manuscript reading, Ingersoll delivered carefully prepared addresses with a conversational rhythm that gave the impression of spontaneity, a technique that heightened his appeal to audiences accustomed to oratory as entertainment.12 His stage presence fused showmanship with argument, transforming the lecture hall into a space where skeptical inquiry became a form of public theater.

Transcriptions of Ingersoll’s lectures circulated almost immediately after delivery, enabling his words to reach audiences far beyond the cities he visited. Stenographers hired by newspapers or lecture sponsors produced versions that appeared in both major dailies and regional periodicals.13 These transcriptions, sometimes published the following morning, extended his influence into homes, clubs, and reading groups that followed the controversies surrounding freethought. The rapid dissemination of his speeches mirrored broader trends in Gilded Age print culture, in which political addresses and courtroom arguments were reproduced for national readerships.14 The widespread circulation of Ingersoll’s remarks helped consolidate his reputation as the leading voice of secular critique in the United States.

Ingersoll’s performances also relied on a distinctive use of timing, pacing, and humor. Contemporary accounts praised his ability to shift from solemn reflection to light remark without disrupting the structure of his argument.15 This approach reflected his legal background, which had trained him to blend persuasion with narrative clarity. The theatrical dimension of his presentations distinguished him from academic lecturers and ministers, whose styles tended toward formal exposition. Ingersoll’s ability to transform complex critiques of biblical interpretation or metaphysical claims into accessible and memorable passages contributed significantly to his popularity on the circuit.

The commercial success of his lectures made freethought a profitable cultural commodity. Contracts with lecture bureaus, especially the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, ensured that Ingersoll’s schedule included cities across the country, from the Northeast to the growing urban centers of the Midwest.16 These tours brought his ideas into communities with varying religious and political attitudes, generating responses that ranged from enthusiasm to organized clerical opposition. Yet even critics recognized the scale of his influence, as editorials and sermons often acknowledged that Ingersoll drew audiences matched only by leading revivalist preachers. His reach on the lecture circuit demonstrated that public skepticism had secured a prominent place within American cultural debate.

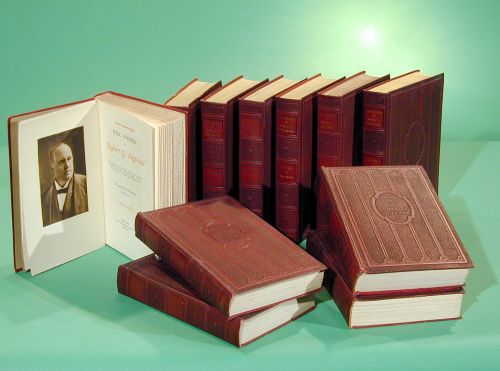

By the 1880s, Ingersoll’s oratorical fame had become central to his national persona. His speeches appeared in multiple authorized editions compiled by his publisher, which further solidified his position as the most widely read freethought writer of his era.17 The lecture circuit served not simply as a venue for performance but as the medium through which his broader intellectual project achieved national visibility. It was in these halls, filled with paying listeners, that Ingersoll forged his reputation as the foremost public critic of traditional religious authority in the Gilded Age.

The Philosophy of Freethought: Reason, Skepticism, and Moral Critique

Ingersoll’s freethought philosophy emerged from a conviction that human progress depended on the rejection of theological authority in favor of scientific inquiry and individual moral reasoning. His lectures repeatedly drew attention to the ways in which traditional biblical narratives conflicted with the expanding body of knowledge produced by geology, biology, and historical criticism.18 These arguments were not presented as abstract philosophical speculation. Instead, Ingersoll framed them as practical questions about the conditions under which free citizens could think, speak, and govern themselves. The appeal of his freethought message rested on its accessibility, inviting listeners to examine long-standing assumptions through the lens of common sense and empirical observation.

A central theme in his writings was the critique of scriptural literalism. In works such as The Gods (1872) and Some Mistakes of Moses (1879), Ingersoll offered detailed examinations of biblical narratives, highlighting internal inconsistencies and the moral difficulties posed by certain passages.19 He argued that religious claims should be evaluated using the same standards applied to historical documents or scientific theories, a position that resonated with audiences who had encountered debates over evolution and higher criticism. This approach allowed him to separate religious institutions from the ethical values he believed were accessible apart from supernatural claims, providing a framework for moral reasoning grounded in human experience rather than divine command.

Ingersoll’s positive moral philosophy emphasized the capacity of individuals to develop ethical lives based on sympathy, justice, and personal responsibility. His lectures frequently addressed themes such as kindness, fairness, and the rejection of cruelty, presenting them as natural products of human sociability rather than the exclusive property of religious doctrine.20 This framing allowed him to challenge assertions that secular life lacked moral foundation, asserting instead that ethical principles emerged from human needs and communal relationships. The moral dimension of his freethought message was therefore as central to his project as its skeptical elements.

He also addressed questions of religious authority and personal freedom. Ingersoll maintained that institutions built on claims of infallibility posed obstacles to intellectual and political liberty.21 He argued that a society committed to democratic participation required an open exchange of ideas, free from coercion or fear of condemnation. This argument drew on broader liberal traditions but gained distinctive shape in his work through its application to contemporary controversies over schooling, public policy, and the role of clergy in civic life. His critique of authority was therefore inseparable from his vision of democracy, making his freethought philosophy a political as well as intellectual project.

Ingersoll’s treatment of the supernatural reflected another dimension of his freethought philosophy. He consistently maintained that claims of miracles, divine intervention, or supernatural revelation required the highest degrees of evidence, and he found none of these claims persuasive.22 His emphasis on evidentiary standards placed him within the broader rationalist tradition of the nineteenth century, linking his work to that of European skeptics and scientific humanists. Yet his presentation was distinctively American, framed within the language of citizenship, republican virtue, and the promise of national progress. These connections broadened the appeal of his arguments beyond strictly secular audiences.

The cumulative effect of these themes positioned Ingersoll as the leading public advocate of freethought in the United States. His philosophy combined rigorous criticism of religious claims with an affirmative defense of intellectual freedom and secular morality.23 Rather than calling for the destruction of religion, he invited audiences to reconsider inherited doctrines through reflection, inquiry, and a commitment to human dignity. This blend of skepticism and ethical affirmation contributed to the enduring legacy of his work and to his prominence within the freethought movement of the late nineteenth century.

Ingersoll and the Politics of the Gilded Age: Republicanism, Reform, and Controversy

Ingersoll’s political career unfolded within the shifting partisan landscape of the Gilded Age, a period marked by internal party divisions, debates over Reconstruction, and struggles over civil service reform. A steadfast Republican, he became one of the party’s most effective and recognizable speakers, particularly during presidential campaigns. Contemporary press reports document his appearances at rallies where thousands gathered to hear him defend Republican positions on economic development, veterans’ rights, and national unity.24 His political identity was therefore inseparable from his public visibility, even as his outspoken agnosticism limited his opportunities for federal appointments.

Central to Ingersoll’s political advocacy was his support for civil service reform. He argued that the patronage system undermined government efficiency and encouraged corruption, a stance that aligned him with reform-minded Republicans who sought to professionalize the federal bureaucracy.25 His speeches in the late 1870s and early 1880s frequently addressed these themes, emphasizing the importance of merit-based appointments and accountability in public office. Although his position reflected broader national debates, Ingersoll’s rhetorical skill amplified the visibility of reformist arguments within his party.

Ingersoll’s role in the 1876 and 1880 presidential campaigns further enhanced his prominence. His nomination speech for James G. Blaine in 1876, often referred to in newspapers as the “Plumed Knight” speech, became one of the most widely circulated political addresses of the era.26 While the speech drew admiration for its stylistic power, it also demonstrated the tensions between his political commitments and his secular reputation. Many Republican leaders hesitated to elevate him within the party hierarchy because his agnosticism risked alienating Protestant voters. Despite this barrier, Ingersoll remained a valued campaign asset whose oratory could energize audiences across diverse regions.

His political thought extended beyond partisan concerns. Ingersoll spoke frequently on issues related to civil liberties, including freedom of speech, religious liberty, and the rights of minority groups. He viewed these principles as essential to the preservation of democratic society, and his arguments echoed those found in his freethought lectures.27 His support for expanded rights for women and his sympathetic commentary on African American citizenship aligned him with progressive currents that circulated within late nineteenth-century reform movements. These commitments reflected his broader conviction that public policy should rest on universal human rights rather than inherited theological assumptions.

The interplay between Ingersoll’s political commitments and his secular philosophy shaped his public identity throughout the Gilded Age. His involvement in Republican politics reinforced his national prominence, but it also exposed him to criticism from religious leaders who viewed his influence as a threat to traditional moral authority.28 The controversies that surrounded his political speeches mirrored those sparked by his freethought lectures, highlighting the degree to which his religious skepticism permeated every aspect of his public life. Ingersoll’s political career therefore provides essential insight into how secular ideas entered mainstream political debate during a period of profound cultural transformation.

Reception and Backlash: Clergy, Press, and Public Debate

Ingersoll’s national prominence ensured that his lectures sparked a wide range of responses, particularly from Protestant clergy who regarded his criticism of biblical authority as a profound threat to religious life. Sermons denouncing his lectures appeared regularly in major city newspapers, often published within days of his appearances. The New York Observer and other denominational journals devoted sustained attention to rebutting his claims, sometimes organizing counter-lectures specifically in response to his visits.29 These reactions reveal the extent to which Ingersoll’s freethought message disrupted the expectations of religious leaders confronting scientific inquiry, historical criticism, and changing patterns of belief in the late nineteenth century.

The secular and general press likewise played a central role in shaping how the public understood Ingersoll. Some newspapers praised his eloquence and welcomed his challenges to inherited dogma, especially those aligned with liberal or reform-oriented political positions. Others framed him as a destabilizing figure whose ideas threatened traditional moral foundations. The Chicago Tribune and St. Louis Post-Dispatch often covered his speeches in detail, printing verbatim excerpts accompanied by commentary on audience reactions.30 These reports constructed Ingersoll as both an entertainer and a cultural force, underscoring the degree to which the lecture hall had become a public forum in which debates over religion unfolded in highly visible ways.

Responses from revivalist preachers highlighted another dimension of the backlash. Figures such as Dwight L. Moody and others within the evangelical revival tradition used their platforms to counter the rise of skepticism that Ingersoll represented.31 Although these preachers rarely engaged directly with the detailed content of his arguments, they often used his speeches as examples of what they considered the dangers of rationalism and secular modernity. Their condemnations circulated alongside press reports of Ingersoll’s lectures, creating parallel public conversations about faith, doubt, and intellectual authority. The revivalist critique illustrated broader anxieties about religious decline and the changing nature of public belief.

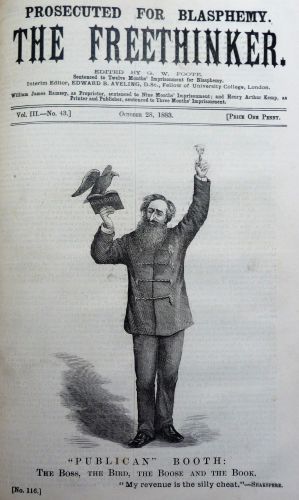

The broader freethought community interpreted these controversies as evidence of shifting cultural norms. Publishers associated with secularist movements, including the Truth Seeker Company, framed clerical backlash as confirmation that religious authority feared open debate.32 These publications often reprinted hostile sermons or negative editorials alongside Ingersoll’s own lectures, presenting them as signs of a society grappling with competing visions of morality and knowledge. The resulting discourse helped define freethought as a movement engaged not merely in philosophical critique but in active participation within the contested public sphere of the Gilded Age.

Despite the intensity of clerical criticism, Ingersoll retained a large and devoted following. His ability to attract substantial audiences even in cities dominated by conservative congregations indicated that many Americans were willing to entertain arguments that challenged traditional religious assumptions.33 The blend of admiration and condemnation that surrounded his public appearances reveals the central position he occupied within national debates over skepticism, modernity, and the boundaries of public discourse. The controversies of his career were therefore not incidental but integral to his historical significance, demonstrating how freethought entered mainstream cultural conversation through sustained public engagement and dispute.

Networks of Freethought: Publishing, Associations, and Influence on Reform Movements

Ingersoll’s influence extended far beyond the lecture hall through the extensive publication and distribution of his writings. His partnership with his publisher ensured that his lectures appeared in carefully edited pamphlets and multi-volume collections. The Dresden Edition of The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll circulated in tens of thousands of copies, making his ideas accessible to readers who never saw him speak in person.34 These editions standardized texts that previously existed only in stenographic newspaper transcripts, allowing Ingersoll to shape his public image and control the presentation of his arguments. The availability of inexpensive pamphlets also ensured that his ideas circulated within clubs, reading groups, and informal associations dedicated to secular inquiry.

Freethought organizations played an important role in sustaining and amplifying his visibility. Groups such as the National Liberal League and later secularist societies regularly invited Ingersoll to speak at conventions or used his lectures as rallying points for debates over blasphemy laws, Sabbath legislation, and public education.35 These associations saw Ingersoll as a symbol of intellectual independence and used his presence to legitimize their positions within national controversies. Their newsletters and journals frequently reproduced his remarks, creating networks through which his ideas traveled across geographic and social boundaries.

Publishing networks linked Ingersoll to other reform movements concerned with civil liberties, women’s rights, and scientific humanism. His speeches appeared alongside writings by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Moncure Conway, and members of the so-called “liberal clergy,” whose work circulated in overlapping venues.36 Ingersoll’s participation in these networks was not limited to ideological affinity. He spoke at events organized by reformers who saw his advocacy of religious liberty as essential to broader struggles for social equality. The convergence of these movements illuminated the ways in which freethought functioned as part of a larger progressive current within American political culture.

The transatlantic dimension of these networks further broadened Ingersoll’s reach. British secularist organizations, including the National Secular Society, distributed his lectures through London publishers who saw in his work a counterpart to European freethinkers.37 These connections enabled Ingersoll’s ideas to travel across national boundaries, linking him to debates in Britain concerning established religion, education, and scientific authority. Although he never toured abroad, his writings circulated widely enough to make him familiar to readers engaged in the broader nineteenth-century discussion over religion and modernity.

Ingersoll’s influence also extended into publishing cultures concerned with popular science. His arguments frequently appeared in periodicals that covered scientific developments or promoted rationalist perspectives. Journals such as The Truth Seeker and The Free Thought Magazine placed his essays alongside discussions of astronomy, geology, and evolutionary theory.38 These alignments reflected the broader appeal of his arguments among readers who viewed science as a source of moral and intellectual authority capable of supplanting traditional religious explanations. The integration of his essays into scientific publishing networks broadened the intellectual foundation of freethought and linked it to emerging understandings of the natural world.

Through these various channels, Ingersoll became not only a prominent lecturer but also a central figure in the institutional life of American freethought. His participation in networks of publishing, association, and reform created an infrastructure that sustained secular inquiry long after his major lecture tours ended.39 These networks help explain the durability of his influence and demonstrate how his ideas became woven into the larger fabric of American intellectual and political culture. Ingersoll’s prominence was therefore not solely the product of his personal charisma but also the result of sustained engagement with organizations and communities committed to advancing secular and democratic values.

Decline in Popular Memory: Why a Household Name Vanished

Ingersoll’s prominence during his lifetime makes the subsequent decline of his public reputation all the more striking. At the time of his death in 1899, newspapers across the country published extended reflections on his career, describing him as one of the most recognizable lecturers of the age.40 Yet within a generation, his name had largely disappeared from mainstream discussions of American cultural history. This shift reflected broader changes in the intellectual and religious climate of the early twentieth century, as new debates over fundamentalism, immigration, and national identity displaced earlier disputes over biblical criticism and freethought. The cultural moment that had elevated Ingersoll to national visibility did not persist.

The rise of fundamentalism in the 1910s and 1920s played a significant role in reshaping the public conversation around religion, casting skepticism and secular critique in a new light. Figures associated with fundamentalist movements frequently invoked concerns about cultural decline, social disorder, and the erosion of religious authority.41 These anxieties differed from the controversies that Ingersoll had confronted in the Gilded Age and contributed to a shift in tone that left less room for the theatrical, lecture-centered rationalism he embodied. The transformation of public religious discourse therefore helped push Ingersoll’s freethought legacy to the margins.

Transformations within secular publishing also contributed to his fading reputation. The lecture circuit that had sustained his popularity diminished as new forms of media reshaped public communication. Motion pictures, radio, and later mass-market magazines provided entertainment and commentary in forms that required neither the civic performance of the lyceum nor the extended rhetorical engagement that characterized Ingersoll’s style.42 As publishers of freethought materials declined in number or shifted their focus, fewer of his works appeared in reprinted editions. This decline in circulation reflected a broader institutional shift, as secular organizations struggled to maintain their earlier visibility.

By the mid-twentieth century, Ingersoll’s name appeared most frequently in histories of American unbelief rather than in accounts of national political or cultural life. Scholars of religion and intellectual history began reassessing his work in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, emphasizing the significance of his contributions to debates over free speech, democratic participation, and secular ethics.43 Yet this scholarly revival did not fully restore his presence in popular memory. The contrast between his enormous influence during his lifetime and his relative obscurity afterward illustrates the contingency of cultural reputation and the ways in which intellectual legacies become reshaped by shifting social priorities. Ingersoll’s trajectory underscores how the landscape of American public discourse evolved as new forms of communication and new religious movements altered the terms of national debate.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Great Agnostic

Robert G. Ingersoll’s career reveals the centrality of public oratory to the intellectual and political life of the late nineteenth century. His lectures offered audiences a model of reasoning that challenged inherited assumptions about scripture, authority, and morality. In doing so, he transformed the lecture hall into a democratic arena in which questions about belief and citizenship could be negotiated in open view. His prominence during the Gilded Age underscores how freethought became part of mainstream public culture rather than a marginal or esoteric pursuit.44 The debates he provoked illuminate the intellectual tensions that characterized a nation grappling with scientific discovery, social reform, and evolving religious identities.

At the same time, Ingersoll’s work extended beyond criticism to articulate a positive moral vision grounded in human sympathy and civic responsibility. His lectures emphasized kindness, fairness, and the need for institutions to respect individual conscience. By framing these values as products of human experience rather than divine command, he offered an ethical framework that resonated with audiences confronted by rapid social and scientific change.45 This affirmative element of his freethought philosophy complicates the view that skepticism in the nineteenth century was merely oppositional, showing instead that it could serve as a foundation for constructive engagement with public life.

The political dimensions of Ingersoll’s career highlight the intersection between secular thought and democratic participation. His support for reform movements, his advocacy for civil liberties, and his insistence on transparent governance reflect a broader vision of citizenship rooted in the free exchange of ideas. Republican leaders relied on his rhetorical skill even as they hesitated to elevate him because of his agnosticism, revealing the contradictions within a political culture balancing traditional religious expectations with new secular currents.46 His political activities therefore form an essential part of his legacy, demonstrating how secular arguments shaped national debates over policy and moral authority.

Ingersoll’s later obscurity does not diminish the significance of his contributions. The recent scholarly revival that situates him within the broader history of American unbelief underscores the enduring relevance of his ideas to contemporary discussions of religious liberty, public reason, and democratic culture.47 His career illustrates the dynamic relationship between belief and public discourse in American history, and it offers a case study in how individuals outside formal political or religious institutions can influence national conversations. Ingersoll’s legacy lies not only in the arguments he advanced but in the public spaces he helped create for critical inquiry, debate, and the affirmation of human dignity.

Appendix

Footnotes

- The New York Times, “Colonel Ingersoll in Chicago,” February 22, 1878.

- Susan Jacoby, The Great Agnostic: Robert G. Ingersoll and American Freethought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 14–27.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, 11 vols. (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902), vol. 1, v–ix.

- Leigh Eric Schmidt, Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 88–103.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 181–192.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 9–13.

- Illinois State Archives, Court Records of Peoria County, docket entries for the 1850s.

- United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), Series I, Vol. 17, 384–386.

- Peoria Daily Transcript, “Hon. R. G. Ingersoll’s Address,” August 21, 1867.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 45–51.

- The Boston Globe, “Ingersoll’s Lecture on the Bible,” January 15, 1880.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 64–72.

- Chicago Tribune, “Colonel Ingersoll’s Address Last Night,” March 7, 1879.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 59–66.

- The New York Times, “Ingersoll at the Academy,” December 23, 1885.

- Carl Bode, The American Lyceum: Town Meeting of the Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), 223–227.

- Ingersoll, The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, Vol. 1, v–xii.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, The Gods (Washington, D.C.: The Truth Seeker Company, 1892), 7–15.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, Some Mistakes of Moses (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1879), 21–37.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, Why I Am an Agnostic (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1896), 10–18.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 103–115.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 134–142.

- Ingersoll, The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, Vol. 3, v–x.

- The New York Times, “Ingersoll at the Republican Rally,” October 5, 1880.

- Robert G. Ingersoll, “Address on Civil Service Reform,” in The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, Vol. 4 (New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902), 112–123.

- Chicago Tribune, “The Plumed Knight Speech,” June 15, 1876.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 152–164.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 71–78.

- New York Observer, “Colonel Ingersoll’s Errors Exposed,” March 12, 1882.

- Chicago Tribune, “Ingersoll at the Opera House,” January 9, 1884.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 108–115.

- The Truth Seeker, “Clerical Replies to Ingersoll,” July 3, 1886.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 137–144.

- Ingersoll, The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, Vol. 1, v–x.

- National Liberal League Proceedings, 1878, reports of annual meetings.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 167–173.

- The National Secular Society Annual Report, London, 1887, 22–26.

- The Truth Seeker, “Scientific Notes and Liberal Thought,” April 10, 1886.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 201–213.

- The New York Times, “Death of Colonel R. G. Ingersoll,” July 22, 1899.

- George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 92–108.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 214–222.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 227–240.

- Schmidt, Village Atheists, 11–19.

- Ingersoll, Why I Am an Agnostic, 29–35.

- Chicago Tribune, “Ingersoll and the Republican Campaign,” October 18, 1880.

- Jacoby, The Great Agnostic, 241–253.

Bibliography

- Bode, Carl. The American Lyceum: Town Meeting of the Mind. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Chicago Tribune. “Colonel Ingersoll’s Address Last Night.” March 7, 1879.

- —-. “Ingersoll and the Republican Campaign.” October 18, 1880.

- —-. “Ingersoll at the Opera House.” January 9, 1884.

- —-. “The Plumed Knight Speech.” June 15, 1876.

- The National Secular Society Annual Report. London, 1887.

- National Liberal League Proceedings. 1878.

- New York Observer. “Colonel Ingersoll’s Errors Exposed.” March 12, 1882.

- The New York Times. “Colonel Ingersoll in Chicago.” February 22, 1878.

- —-. “Death of Colonel R. G. Ingersoll.” July 22, 1899.

- —-. “Ingersoll at the Academy.” December 23, 1885.

- —-. “Ingersoll at the Republican Rally.” October 5, 1880.

- Peoria Daily Transcript. “Hon. R. G. Ingersoll’s Address.” August 21, 1867.

- Illinois State Archives. Court Records of Peoria County. Docket entries for the 1850s.

- Ingersoll, Robert G. Some Mistakes of Moses. New York: C. P. Farrell, 1879.

- —-. “Address on Civil Service Reform.” In The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Dresden Edition, Vol. 4, 112–123. New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902.

- —-. The Gods. Washington, D.C.: The Truth Seeker Company, 1892.

- —-. The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll. Dresden Edition. 11 vols. New York: C. P. Farrell, 1902.

- —-. Why I Am an Agnostic. New York: C. P. Farrell, 1896.

- Jacoby, Susan. The Great Agnostic: Robert G. Ingersoll and American Freethought. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Schmidt, Leigh Eric. Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- The Truth Seeker. “Clerical Replies to Ingersoll.” July 3, 1886.

- —-. “Scientific Notes and Liberal Thought.” April 10, 1886.

- United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. 17. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.