Internet Relaty Chat (IRC) illustrates how early internet technologies established conceptual frameworks that shaped the development of digital communication.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Emergence of Real-Time Digital Communication

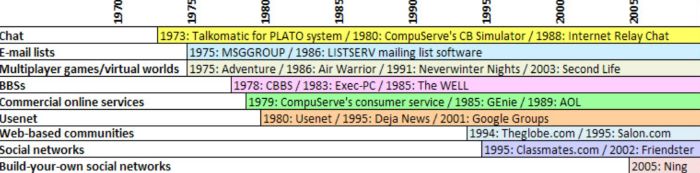

The late 1980s marked a transitional moment in the history of digital communication as researchers and hobbyists experimented with ways to connect users in synchronous conversation across distributed networks. Early forms of online interaction had relied heavily on asynchronous systems such as electronic mail and Usenet, both of which emphasized delayed exchange and threaded discussion.1 Real-time communication, by contrast, required continuous connectivity between machines and protocols that could support simultaneous messages flowing across multiple nodes. The technical and cultural conditions for this shift emerged slowly through university networks, bulletin board systems, and the growing interoperability of the global internet.2

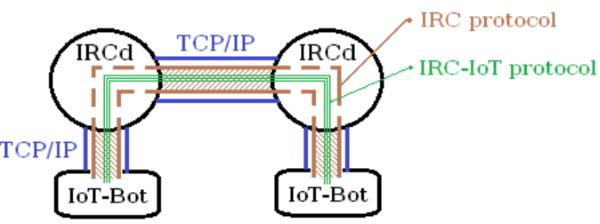

Internet Relay Chat appeared within this landscape in August 1988 as an experiment in linking users through a live, multi-user environment. Jarkko Oikarinen developed the first version of IRC at the University of Oulu in Finland, drawing on earlier chat functions used on the local OuluBox system.3 His design introduced a client-server model in which messages could be exchanged instantly between participants distributed across national and institutional networks. The innovation lay not only in the software but also in the assumption that users might want to converse publicly and continuously across geographically distant machines. This model diverged from the localism of BBS culture and signaled a shift toward communication practices structured by global rather than regional networks.4

The emergence of IRC also reflected the accelerating growth of the internet itself. As universities and research institutions adopted networked Unix systems, users gained access to a shared communication infrastructure that made synchronous exchange feasible across long distances. The Internet Society has noted that the rapid proliferation of interconnected networks during the late 1980s created the conditions under which real-time tools could flourish.5 IRC arrived at precisely the moment when technical capacity, institutional use, and user interest converged. It offered a framework for interaction that differed fundamentally from earlier forms of online exchange and laid the foundation for the real-time digital environments that would follow.

By the early 1990s, IRC had already influenced expectations about immediacy, presence, and community in online communication. The protocol’s architecture allowed participants to gather in shared spaces, observe conversations in real time, and interact with strangers and acquaintances across international boundaries. These features positioned IRC as one of the earliest platforms to demonstrate how synchronous communication could reshape social life on the internet.6 The system’s significance therefore extends beyond technical innovation. It represents a historical turning point in how users understood what networked communication could be and how global communities might form inside digital space.

Origins in Finland: Jarkko Oikarinen and the OuluBox Environment

IRC emerged in August 1988 within the computing environment of the University of Oulu, where Jarkko Oikarinen sought to improve the real-time communication tools available on local systems.7 Oikarinen has stated that his work drew directly from earlier chat programs used on OuluBox, a Finnish BBS-like environment that supported small user communities.8 The limitations of these earlier tools, particularly their confinement to single machines or local nodes, created an incentive to develop a system capable of linking users across larger networks. IRC began as a response to this constraint and reflected a desire to extend conversation beyond the boundaries of a single institution.

The environment in which IRC was created shaped its technical assumptions. Finnish computing in the late 1980s was closely tied to university research networks, and students often relied on Unix-based systems that encouraged experimentation with networked communication.9 Oikarinen’s decision to adopt a client-server model aligned with these systems and allowed his program to scale more effectively than BBS chat software, which typically functioned through direct terminal connections. This approach enabled multiple clients to join the same discussion through interconnected servers, establishing a communication model that differed significantly from the point-to-point exchanges common in earlier platforms.

IRC’s early structure also reflected the international reach of emerging networks between European institutions. As universities expanded their internet connectivity, developers and researchers became accustomed to working across national boundaries.10 The architecture Oikarinen introduced allowed IRC servers to link across these networks with minimal administrative overhead, which in turn encouraged early adoption outside Finland. This distributed design contributed to the system’s rapid spread, since new sites could join simply by running compatible server software and establishing trust relationships with existing nodes.

The decision to release IRC publicly reinforced its growth and ensured that its protocols would circulate far beyond its original context. By 1989, the software was already in use on networks that connected universities across Europe, demonstrating that the original design had anticipated the needs of users operating in a rapidly expanding internet environment.11 The system’s origins therefore lie not only in local innovation but also in the broader culture of experimentation that defined research computing at the close of the 1980s. IRC became possible because its creator stood at the intersection of institutional infrastructure, open development practices, and a growing belief that digital communication could extend beyond regional networks to encompass global communities.

Early Expansion and Client Development, 1988–1990

IRC expanded beyond its origins at the University of Oulu within months of its initial deployment. Oikarinen has described how early adopters in Finland began connecting additional servers to the original network during the late months of 1988, creating the first distributed set of IRC nodes.12 This expansion occurred at a moment when universities across Europe were rapidly extending their internet connectivity, and IRC offered a means of experimenting with synchronous communication across these new links. The system’s client-server model made it possible for geographically distant machines to join a shared communication space without requiring substantial reconfiguration of institutional networks.13

As IRC moved beyond Finland, the availability of Unix systems played an important role in its adoption. Universities and research institutions had already standardized much of their infrastructure around Unix environments, which supported the compilation and distribution of portable client software.14 Because IRC relied on a text-based interface and required limited computational resources, it could be adopted quickly by sites that already maintained multiuser Unix machines. This compatibility distinguished IRC from many BBS-based chat tools, which typically required proprietary hardware or local terminal access.

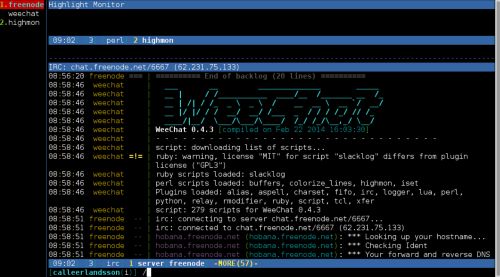

The emergence of early clients shaped the network’s growth during this period. ircII, which became one of the most influential IRC clients for Unix systems, appeared in this early phase and provided features that made participation more accessible for users accustomed to command-line environments.15 Its design encouraged scripting, customization, and rapid adaptation to evolving network norms. The availability of a robust client accelerated IRC’s visibility on academic networks, since it reduced the barriers to joining discussions and interacting with users across multiple channels.

By 1990, the expansion of IRC had produced a substantial international user base. The Internet Society notes that the broader growth of interconnected research networks during this period increased the demand for real-time communication tools that could operate across diverse institutions.16 IRC fulfilled this need by providing a channel-oriented architecture that supported large groups without requiring centralized control. As new universities joined the network, they could connect servers that mirrored channel structures, enabling users to participate in conversations that spanned multiple continents. This distributed design became one of IRC’s defining characteristics and contributed to its rapid adoption in academic and technical communities.

The accumulation of users and servers during this period also prepared IRC for the cultural visibility it would gain in the early 1990s. Oikarinen’s decision to allow open redistribution of the server and client code made it possible for developers and administrators to modify software as needed, encouraging a decentralized culture of experimentation.17 This openness allowed IRC to evolve quickly and incorporate technical improvements introduced by administrators managing different parts of the network. The first years of expansion therefore established the foundation for a system that could scale, adapt to varied institutional environments, and support the real-time digital communities that would define its next decade.

Crisis Communication and the Gulf War: IRC’s Public Visibility (1991)

IRC entered global public awareness during the 1991 Gulf War, when users relied on the network to share real-time information about events unfolding in Kuwait and Iraq. The Internet Society notes that IRC channels became informal spaces where individuals exchanged reports and attempted to verify news during the early stages of the conflict.18 This use of IRC demonstrated how a tool originally designed for technical communication could function as a medium for witnessing geopolitical crises. The presence of users from different regions in the same discussion space emphasized the system’s ability to support synchronous participation across national boundaries.

The Gulf War highlighted the contrast between IRC’s decentralized structure and the centralized flow of information provided by traditional news outlets. Because IRC relied on distributed servers rather than a single authority, users could join channels created spontaneously in response to unfolding events.19 This flexibility allowed for rapid dissemination of personal accounts, technical updates, and commentary that would not have been available through conventional broadcast media. Although the accuracy of information varied, the ability to communicate instantly across continents represented an important milestone in the evolution of global digital communication.

The visibility of IRC during this period also reflected its growing international user base. Oikarinen has discussed how the network had expanded beyond Europe by the early 1990s, supported by institutions that adopted the protocol for research and communication.20 The Gulf War demonstrated the scale that IRC had achieved by that point and showed how real-time systems could serve social functions that extended far beyond their original context. Participation in wartime channels introduced many new users to IRC and contributed to the cultural identity that formed around the platform during the decade.

The events of 1991 revealed how technical design influenced IRC’s social role. The client-server model described in RFC 1459 made it possible for large numbers of users to participate simultaneously, while the channel structure allowed discussions to organize themselves around specific topics or events.21 These features enabled the creation of real-time communities capable of responding collectively to breaking news. The Gulf War therefore marked a significant moment in IRC’s history by demonstrating its potential as a global communication medium and illustrating how early internet systems could shape public understanding during international crises.

Standardization and Governance: RFC 1459 and Protocol Formalization (1993)

The publication of RFC 1459 in May 1993 marked the first formal attempt to document the technical foundations of Internet Relay Chat.22 The RFC outlined the client-server architecture that had defined IRC from its early years and established a framework for message handling, nickname registration, and channel creation. By codifying these elements, the document provided a shared reference for developers who maintained software across a growing number of networks. The RFC served not as a prescriptive rule set but as a descriptive account of a protocol that had already undergone years of organic development.

Standardization through RFC 1459 also clarified design choices that distinguished IRC from earlier communication systems. The document emphasized the importance of distributed servers that could operate independently while still participating in a shared network.23 This approach allowed administrators to maintain local control over their systems while supporting global communication. The flexibility of IRC’s design reflected the broader culture of the early internet, where interoperability and minimal central authority were valued. The RFC helped preserve these principles by recording them at a moment when the network was expanding rapidly.

The creation of an official protocol description contributed to the stability of IRC during a period of growth that introduced significant technical challenges. Server operators confronted issues such as network fragmentation, nickname collisions, and inconsistent implementations of core features.24 Documenting the protocol gave administrators and developers a common vocabulary for addressing these problems. It also encouraged compatibility among server versions, which was essential for keeping large, interconnected networks functioning smoothly. Without such coordination, the increasing number of users and servers could have undermined IRC’s reliability.

RFC 1459 provided a basis for later discussions about network governance and protocol evolution. As the number of IRC networks increased, developers debated how closely new implementations should adhere to the original specification.25 These debates mirrored broader questions about governance on the early internet, where open protocols allowed for innovation but required shared norms to maintain interoperability. By capturing the essence of IRC as it existed in the early 1990s, the RFC served as both a technical reference and a historical snapshot of a communication system that had already transformed online interaction.

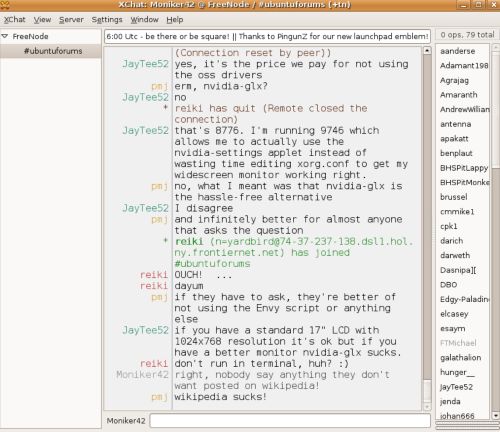

The Social Architecture of IRC: Channels, Moderation, and Community Norms

IRC introduced a social architecture that shaped how users interacted in real-time digital environments. Central to this structure were channels, which served as open or restricted spaces where participants could gather for conversation. RFC 1459 defined channels as logical groupings of users connected through distributed servers and described how clients could join, leave, and communicate within them.26 This model allowed users to create new channels spontaneously, establishing discussion spaces without administrative approval. The relative ease with which users could form and dissolve channels contributed to the dynamic social landscape of IRC and encouraged the formation of communities organized around shared interests.

The role of channel operators further defined IRC’s social environment. Operators held privileges that allowed them to set channel modes, enforce rules, and remove disruptive participants. These mechanisms were described in the protocol as essential tools for maintaining order in decentralized networks.27 Because IRC lacked centralized oversight, the authority granted to operators created a distributed governance model in which individual communities developed their own norms. Operators acted as moderators who balanced openness with the need to prevent conflicts that could disrupt conversation. Their presence underscored IRC’s reliance on social negotiation rather than formal regulation.

Community norms also emerged from the technical constraints of the system. The possibility of nickname collisions, server splits, and rapid fluctuations in user presence encouraged communication practices that adapted to instability.28 Users developed expectations about how to behave during disruptions, such as rejoining channels after splits or acknowledging when messages failed to propagate across servers. These informal norms shaped the culture of IRC and contributed to a shared understanding of how to navigate an environment with unpredictable network behavior. Technical limitations therefore played a direct role in shaping the social coherence of IRC communities.

The public nature of most channels fostered both collaboration and conflict. Users could join discussions without invitation, which encouraged openness but also introduced challenges related to unwanted behavior. The Internet Society notes that early internet communities valued experimentation and inclusivity, and IRC reflected these ideals by allowing broad access to public channels.29 Yet the absence of centralized moderation meant that conflicts had to be managed locally by operators or through collective user action. This created an environment in which social structures evolved organically and in response to real-time interaction rather than formal rules.

Private messaging offered a contrasting form of communication that complemented channel-based interaction. The protocol included explicit support for direct messages between users, enabling conversations that bypassed the public spaces where most discussions occurred.30 This dual structure of public and private interaction anticipated later real-time communication platforms that combined group spaces with individual messaging. The ability to shift between these modes gave IRC users flexibility in how they engaged with the network and allowed for a range of social relationships to develop, from casual acquaintances to long-term collaborations.

As IRC communities grew, users developed shared codes of conduct that balanced technical capabilities with social expectations. The oral history of Oikarinen documents how channel culture varied across networks but often emphasized cooperation, mutual respect, and adaptability.31 These values reflected both the ethos of academic computing communities and the practical need to maintain functional communication spaces. The decentralized social architecture that emerged from these practices influenced later platforms by demonstrating how real-time networks could sustain communities built on voluntary norms and distributed authority.

Technical Affordances and Limitations Shaping Behavior

IRC’s technical design directly influenced the behavior of its users and the culture that formed around the network. RFC 1459 documented a system that relied on interconnected servers to maintain a shared state across geographically distributed machines.32 This architecture enabled real-time communication but also introduced instability when network links failed or servers disagreed about user presence. The protocol did not attempt to conceal these limitations, and users quickly developed expectations about the volatility of the network. The conditions of early IRC therefore shaped habits of resilience and improvisation among participants who navigated these disruptions as a routine part of digital life.

Server splits became one of the most distinctive features of IRC’s technical environment. When links between servers broke, the network temporarily fragmented into isolated segments that contained different versions of channel membership and user lists.33 Such splits created moments of confusion, opportunity, and sometimes conflict, as users experienced duplicate nicknames, competing claims to channel authority, and divergent conversations across partitions. Because splits were visible and often frequent, they became part of the cultural fabric of IRC rather than a purely technical malfunction. Users learned to reestablish presence and authority once the network rejoined, reinforcing community norms that centered on adaptability.

Nickname collisions offered another example of how technical limitations shaped social behavior. The protocol required unique nicknames across a network, yet splits or rapid reconnects could create situations in which two users attempted to occupy the same identity.34 Collisions forced one or both users to change names and highlighted the fragility of identity in early real-time platforms. This dynamic encouraged participants to adopt identifiers that were both recognizable and resilient to disruption, contributing to a culture in which identity was negotiated through a combination of technical constraints and social recognition. The instability of nicknames served as a reminder that IRC identities were contingent on network conditions as much as on individual choice.

Bandwidth limitations further influenced how users communicated. The Internet Society notes that early internet links were narrow by modern standards, which restricted the volume and speed of messages that servers could handle.35 IRC clients and servers were therefore designed with efficiency in mind, relying on compact text commands and minimal overhead. These constraints encouraged concise communication and favored users who understood the technical underpinnings of the protocol. Over time, this contributed to a distinctive linguistic culture in which brevity, command familiarity, and technical fluency played significant roles in shaping interaction. The relationship between technical limits and social practice became one of the defining characteristics of IRC’s early years.

IRC in Open-Source Culture and Developer Communities

IRC became a central tool in the emerging open-source and free software movements of the early 1990s. Distributed developer communities required communication channels that supported real-time collaboration across institutions and national boundaries, and IRC offered a solution that aligned with their values of openness and decentralization. The Internet Society notes that the expansion of global research networks created opportunities for new forms of technical cooperation, and IRC became one of the platforms that enabled such collaboration.36 Its channel-based structure allowed developers to gather in shared spaces, coordinate tasks, and address problems as they arose, which contributed to the rapid growth of international programming communities.

The protocol’s reliance on open standards made it especially suitable for communities centered on free software. RFC 1459 documented a system that could be implemented by anyone with the technical skill to run a server, which allowed project teams to establish their own communication environments without relying on commercial providers.37 This openness paralleled the ethos of early open-source development, where transparency and communal oversight were considered essential. Developers used IRC to maintain persistent communication networks that supported both formal decision-making and informal discussion. The structure of IRC therefore reinforced the social dynamics of open-source work by providing accessible tools for coordination.

IRC also played a role in shaping the workflow of major software projects. The Computer History Museum’s oral history with Oikarinen confirms that by the early 1990s, developers working on Linux, BSD variants, and other collaborative systems used IRC channels to organize contributions and troubleshoot issues.38 These channels served as virtual meeting spaces in which participants could discuss patches, share logs, and test new features. The immediacy of IRC communication reduced the delays associated with email-based collaboration and helped establish a rhythm of development that relied on rapid feedback cycles. As a result, IRC influenced both the speed and the structure of open-source production.

The persistence of IRC within open-source communities illustrates the longevity of its design. Although later platforms introduced graphical interfaces and integrated development tools, IRC remained widely used because of its simplicity, portability, and alignment with Unix-based environments. The Internet Society emphasizes that early internet systems often survived because they adapted well to the needs of specialized communities, and IRC exemplifies this pattern.39 Its text-based architecture, low resource requirements, and flexible social organization allowed it to remain relevant in a domain that valued stability and openness. IRC’s enduring role in open-source development demonstrates how early communication protocols helped establish the practices that continue to define collaborative software engineering.

Decline, Persistence, and Legacy

IRC’s decline in mainstream visibility during the late 1990s and 2000s reflected broader changes in internet architecture and user expectations. As commercial internet access expanded, new platforms emerged that offered integrated interfaces, automated moderation tools, and features designed for users unfamiliar with command-line systems.40 These developments made graphical chat environments more accessible to people who had not participated in early Unix-based cultures. While IRC remained widely used in technical communities, the rise of commercial messaging systems shifted the center of online conversation toward platforms that prioritized ease of use and centralized administration.

Despite losing prominence among general users, IRC persisted because its technical design continued to meet the needs of communities that valued openness, transparency, and minimal barriers to entry. The Internet Society notes that many early internet tools endured not because they appealed to mass audiences but because they provided stability and flexibility in specialized contexts.41 IRC exemplified this pattern by allowing administrators to control their own servers and communities without relying on proprietary infrastructure. This independence remained an advantage for groups that required communication channels free from commercial oversight or restrictive policies.

The protocol’s longevity also stemmed from the culture that formed around it. IRC communities developed norms that adapted to the system’s technical constraints, such as server splits and nickname limitations.42 These practices created resilient networks capable of surviving fluctuations in user populations and the emergence of new technologies. IRC’s decentralized governance allowed individual networks to persist even when others declined, ensuring that the system as a whole remained active long after mainstream users migrated to newer platforms.

IRC’s influence extended beyond its own user base into the design of later communication systems. The channel model, operator hierarchy, and real-time message flow described in RFC 1459 provided conceptual frameworks for platforms ranging from early instant messaging programs to contemporary collaborative tools.43 Many modern systems preserve the distinction between public group spaces and private messaging that IRC introduced. These structural continuities demonstrate how foundational IRC has been in shaping expectations about online communication, even when later technologies employ graphical interfaces and more complex integration features.

Today IRC occupies a dual position as both a legacy technology and an active tool within certain domains. It remains embedded in the workflows of open-source development, technical support communities, and long-standing internet subcultures. The Internet Society notes that early internet technologies often leave a lasting imprint because they influence how users conceptualize interaction and community formation.44 IRC’s persistence exemplifies this phenomenon. Although no longer central to mainstream online communication, it continues to anchor practices and norms that emerged during the formative years of the global internet. Its legacy endures in the platforms that followed and in the communities that maintain it as a living artifact of digital history.

Conclusion: IRC and the Long Arc of Networked Communication

IRC illustrates how early internet technologies established conceptual frameworks that shaped the development of digital communication. Emerging at a moment when synchronous interaction across distributed networks was still uncommon, IRC demonstrated that real-time conversation could function reliably at a global scale. Its architecture showed how channels, operators, and client-server relationships could be used to organize interaction across many users and servers. The documentation in RFC 1459 preserved these ideas at a formative moment in internet history, ensuring that future developers had a reference point for understanding the logic behind real-time protocols.45

The system’s influence extended beyond its technical implementation. IRC encouraged practices of collaboration that helped define the culture of the early internet. Users accustomed to asynchronous communication through email and Usenet encountered new forms of presence and immediacy that reshaped expectations about how digital communities might operate. The Internet Society notes that early real-time platforms played an important role in expanding opportunities for global interaction.46 IRC became a model for environments in which geographically dispersed individuals could gather in shared spaces and contribute to conversations unfolding in real time. These experiences informed the design of later platforms that built upon IRC’s conceptual foundations.

IRC’s legacy is also evident in the open-source communities that adopted it as a principal tool for coordination. The oral history of Oikarinen at the Computer History Museum documents that developers used IRC to maintain persistent communication channels for discussing patches, testing features, and organizing contributions.47 These practices helped establish collaborative norms that persist in modern software development. Even as graphical and integrated communication tools replaced text-based interfaces for many users, IRC remained a functional and reliable solution within technical communities that valued simplicity and transparency.

The long history of IRC underscores how early internet systems shaped not only communication technologies but also the social dynamics that developed around them. Although it no longer occupies a central place in mainstream digital interaction, IRC continues to demonstrate the durability of open protocols and decentralized governance. The Internet Society notes that technologies from the internet’s early decades often retain influence because they define expectations about how communication should occur across networks.48 IRC’s impact persists in the structure of contemporary real-time systems, the cultural practices of developer communities, and the memory of an era when global digital conversation first emerged.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen.”

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen.”

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- ircII Client Documentation, early Unix distribution notes, accessed via https://www.irc.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol.

- Oikarinen and Reed, RFC 1459.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Oikarinen and Reed, RFC 1459.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Oikarinen and Reed, RFC 1459.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Oikarinen and Reed, RFC 1459.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet.”

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

- Computer History Museum, “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen,” 2013, https://computerhistory.org.

- Jarkko Oikarinen and Darren Reed, RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol, May 1993.

- Internet Society, “A Brief History of the Internet,” accessed 2025, https://www.internetsociety.org.

Bibliography

- Computer History Museum. “Oral History of Jarkko Oikarinen.” 2013. https://computerhistory.org.

- Internet Society. “A Brief History of the Internet.” Accessed 2025. https://www.internetsociety.org.

- ircII Project. ircII Client Documentation. Early Unix distribution notes. Accessed via https://www.irc.org.

- Oikarinen, Jarkko, and Darren Reed. RFC 1459: Internet Relay Chat Protocol. May 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.