The encounter between African religions and Christianity in the Americas produced spiritual systems that were neither simple adaptations nor imitations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Religion as Survival, Adaptation, and Power

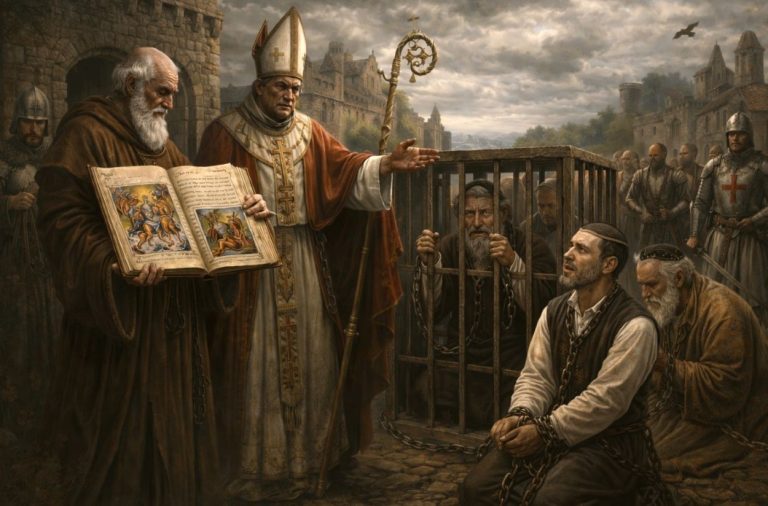

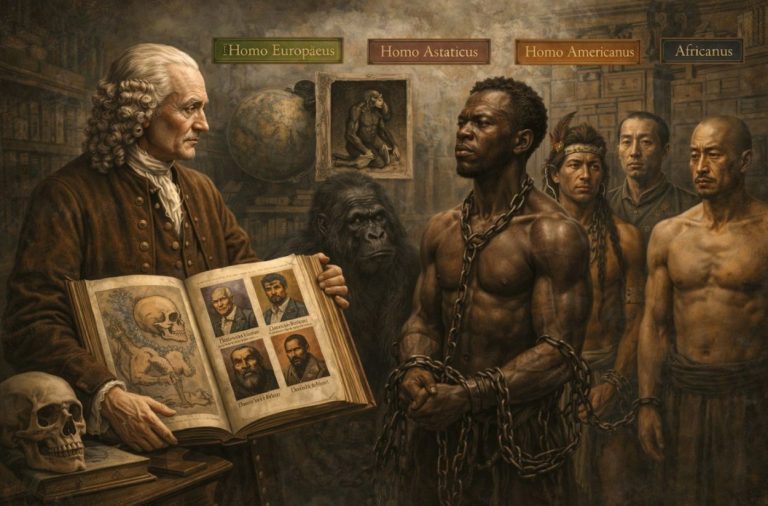

The forced migration of millions of Africans into the Americas fractured languages, kinship systems, and ritual landscapes, yet religion endured as a medium through which the enslaved rebuilt meaning in a world designed to strip it away. Christianity, imposed by slaveholders as a civilizing and controlling instrument, never entered enslaved communities as an empty vessel. It met existing African cosmologies capable of absorbing, reshaping, and redirecting new symbols toward the needs of a traumatized people. The result was not simple conversion but a creative process through which African-descended communities forged spiritual systems that preserved memory, sustained communal bonds, and articulated visions of liberation even in the midst of unfreedom.1

This transformation was neither uniform nor passive. Africans from West and Central Africa carried with them complex religious structures that envisioned a supreme creator, intermediary powers, ancestral presence, and ritual technologies of healing and protection. When Christian teachings reached plantation quarters, they were filtered through these existing frameworks, allowing enslaved people to reinterpret biblical figures, sacred objects, and ritual practices in ways that aligned with their cosmologies. As scholars of African American religion have shown, syncretism did not erase African traditions; it reconfigured them within a new and often hostile environment, producing distinct forms of Black Christianity, Hoodoo, and, in different regional contexts, Vodou.2 This blending created spiritual worlds capable of sustaining interior freedom even where physical autonomy was denied.

Religion also offered a means of collective organization and resistance. Enslaved people used Christian gatherings to claim authority over their own spiritual lives, developing institutions that later became engines of community formation, political mobilization, and cultural continuity.3 Far from mirroring the institutional religion of slaveholders, Black Christian practice adopted the narratives of bondage and deliverance as tools for envisioning liberation. Figures like Moses, the Promised Land, and the Exodus story were not abstract metaphors but functional languages of survival and coded resistance, grounded in African modes of interpretation and performance.4 These systems allowed enslaved communities to narrate their condition and imagine its end, transforming forced exposure to Christianity into a foundation for autonomy.

The history of African American religion, then, is the history of cultural power under constraint. Syncretism became a strategy for preserving what could not be openly practiced, resisting what could not be directly challenged, and creating new forms of identity in a society built on erasure.5 The survival of African concepts within American religious life was never accidental: it was an assertion of humanity amid dehumanization, a reconstruction of meaning amid rupture, and a testament to the capacity of enslaved people to transform imposed structures into sources of strength.

African Cosmologies Before Enslavement: Creator, Intermediaries, Ancestors

Before their forced removal to the Americas, West and Central African peoples practiced religious systems organized around a supreme creator whose distance from daily affairs made intermediary powers essential for navigating the spiritual world. These cosmologies varied across regions, but many shared the idea of a creator deity responsible for ordering the universe without necessarily overseeing its everyday maintenance. In Yoruba traditions, Olodumare functioned as the ultimate source of life, while the Akan recognized Nyame as the supreme sky god.6 These deities were acknowledged through ritual speech and offerings, yet their remoteness meant that spiritual engagement occurred primarily through lesser divinities who mediated human concerns.

Across these societies, intermediary spirits (whether Orishas among the Yoruba, Abosom among the Akan, or the spirit-forces associated with minkisi in the Kongo region) played central roles in regulating health, fertility, justice, and communal harmony.7 These beings were neither abstract symbols nor metaphors; they were practical presences invoked through ceremonies, divination, and specialized ritual objects. Their power offered a structured way to interpret misfortune, seek healing, and maintain order within community life. Because these intermediaries addressed the immediate needs of the living, they shaped expectations about what effective spiritual practice should accomplish.

Ancestral reverence formed another foundational element of these religious worlds. For many West and Central African groups, ancestors were not distant memories but active participants in communal well-being. They safeguarded lineage, sanctioned moral behavior, and mediated disputes within extended families.8 Rituals honoring ancestors (including offerings, praise traditions, and burial practices) sustained ties between generations and reinforced collective identity. The social authority of elders in many African societies drew legitimacy from these ancestral connections, which remained potent even under the pressures of enslavement.

Ritual specialists such as diviners, herbalists, and healers operated as interpreters of the spiritual world. Through techniques like Ifa divination among the Yoruba or nganga healing practices in Kongo regions, these specialists mediated between spiritual forces and everyday human concerns.9 Their knowledge encompassed both metaphysical and medicinal expertise, demonstrating how religion and healing were deeply intertwined. These traditions did not separate physical from spiritual well-being; instead, they approached illness, conflict, and uncertainty through holistic frameworks that addressed both body and spirit.

Communal ritual practices further underscored the integration of spirituality into social life. Festivals, initiations, and collective celebrations featured drumming, dance, call-and-response singing, and patterned movements that reinforced shared identity and transmitted cultural memory.10 These embodied forms of worship cultivated a sense of belonging and continuity, ensuring that religious knowledge remained accessible across generations. When enslaved Africans later encountered Christian worship, these ritual aesthetics provided a familiar medium through which new religious expressions could develop.

African cosmologies provided enslaved people with conceptual and ritual tools that could survive, even if partially transformed, under the extreme violence of the Atlantic slave trade. Belief in a supreme creator, reliance on intermediary spirits, reverence for ancestors, and the authority of ritual specialists collectively shaped how Africans interpreted new religious symbols in the Americas.11 These structures did not disappear upon arrival; they became the scaffolding upon which syncretic traditions grew, enabling displaced communities to reinterpret Christianity through frameworks forged long before enslavement.

Points of Contact: How African Cosmologies Mapped Onto Christianity

When enslaved Africans encountered Christianity in the Americas, they did not meet it as a blank slate. The conceptual architecture of African religions (centered on a supreme creator, intermediary spirits, and the active presence of ancestors) gave them a framework for interpreting unfamiliar Christian teachings. For many, the Christian God resembled distant creator deities such as Olodumare or Nyame, while Jesus appeared as a mediator who bridged divine and human realms.12 These resonances made Christianity intelligible through African categories, allowing the enslaved to adapt new religious symbols without abandoning older cosmologies.

Christian angels and saints also aligned with African understandings of lesser divinities and spirit-forces. In West and Central Africa, Orishas, Abosom, and Lwa mediated healing, justice, fertility, and protection; in the Americas, many enslaved people perceived saints or angelic beings as occupying comparable positions of spiritual authority.13 Catechisms and prayers introduced by missionaries did not erase this structure but became layered with African meanings. These interpretive strategies did not replicate African religions directly but redirected Christian imagery into familiar relational patterns, ensuring continuity of worldview amid displacement.

Material culture offered another point of convergence. In Kongo and Yoruba traditions, objects such as minkisi, amulets, charms, and ritual bundles served as conduits for spiritual power. Enslaved Africans, especially those in Protestant regions where material sacramentals were limited, reinterpreted holy water, printed Bibles, devotional medals, and protective passages such as Psalms within existing frameworks of ritual efficacy.14 Christian objects did not replace African technologies of protection; they supplemented them, offering new forms through which older practices could survive under surveillance. Syncretism, in this context, was both pragmatic and creative.

Ritual specialists likewise found ways to adapt their roles within the new religious landscape. Figures who once mediated between spirits and communities (diviners, healers, and ritual leaders) often became prayer leaders, lay preachers, or recognized sources of spiritual authority in plantation quarters.15 Christianity provided new narratives, but African understandings of spiritual power shaped how those narratives were deployed. Even where formal conversion was enforced, Africans identified continuities between their own systems of mediation and the structures of Christian pastoral care, enabling them to exercise influence within reconfigured religious spaces.

These convergences formed the foundation for more fully developed syncretic traditions that later emerged across the African diaspora. By reading Christian teachings through African epistemologies, enslaved communities transformed a doctrine imposed from above into a spiritual system capable of addressing their lived realities.16 This interpretive flexibility laid the groundwork for the rise of Black Christianity, Hoodoo, and Vodou, religions that bore unmistakable traces of African cosmology even as they engaged Christian texts and symbols. The encounter between African religion and Christianity was thus not one of replacement but of transformation, setting the stage for new spiritual forms rooted in both continuity and adaptation.

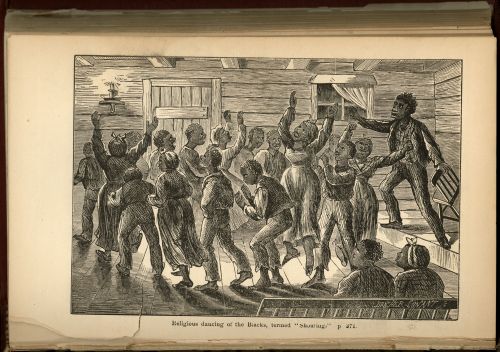

Ritual, Music, and Embodied Worship: African Aesthetics in Christian Practice

The encounter between African ritual traditions and Christian worship produced a distinct expressive culture that reshaped the religious landscape of enslaved communities. African societies had long used music, dance, and rhythmic movement as core components of spiritual communication, linking bodily expression to the activity of spirits and ancestors. When enslaved Africans entered Christian spaces, these embodied forms of devotion became avenues through which older ritual sensibilities survived.17 Although enslavers often sought to regulate or suppress them, the continuity of embodied worship proved remarkably durable across generations.

Drumming, central to many West and Central African ceremonies, was frequently banned on plantations because of its communicative power and its association with rebellion. Yet the absence of drums did not eliminate the rhythmic foundation of African worship. Enslaved people created percussive substitutes (handclapping, foot-stomping, and the polyrhythmic interplay of voices) that reproduced the communal pulse of African ritual life.18 These patterns later became defining features of African American Christian worship, where rhythm structured not only music but also prayer, testimony, and preaching.

The call-and-response format, widespread across African religious and social traditions, also carried into Christian gatherings. It provided a means for worshipers to participate actively in sermons and songs, transforming religious services into communal events rather than hierarchical performances.19 The format facilitated collective affirmation, reinforced shared narratives of suffering and hope, and enabled the transmission of religious ideas through a dynamic, participatory medium. This practice both preserved African communicative structures and adapted them to new theological contexts.

One of the most significant expressions of continuity was the ring shout, a counterclockwise movement accompanied by song, clapping, and spiritual intensity. Though outwardly framed as Christian praise, its structure and aesthetic drew directly from African ritual circles associated with spirit possession, healing, and communal affirmation.20 The ring shout allowed participants to merge Christian themes with African modes of ecstatic expression, creating a worship form that was simultaneously innovative and deeply rooted in ancestral practice. It also provided emotional release and solidarity within the dehumanizing conditions of enslavement.

African musical values shaped the evolution of Christian hymnody within Black communities as well. European-derived hymns introduced by missionaries and slaveholders were frequently reinterpreted through African vocal techniques, including melisma, improvisation, and tonal variation.21 These adaptations transformed the hymns’ affect and meaning, making them responsive to the lived experiences of enslaved people. Through this process, Christian songs acquired expressive depth that spoke to suffering, endurance, and collective longing in ways that mirrored African spiritual aesthetics.

Through these layered adaptations, enslaved Africans forged a worship tradition that transcended imposed religious structures. Embodied practices (rooted in rhythm, communal participation, and spiritual intensity) preserved African principles even within Christian frameworks.22 Rather than disappearing under the weight of forced conversion, African ritual knowledge became the driving force behind a new religious culture that blended inheritance with innovation and laid the foundations for worship styles that remain central to African American Christianity today.

Syncretic Systems: Black Christianity, Hoodoo/Conjure, and Vodou

The blending of African religious frameworks with Christian teachings produced several distinct spiritual systems across the African diaspora in North America and the Caribbean. The most widespread of these was the development of Black Christianity, a form of Protestantism shaped by African epistemologies and ritual aesthetics. While enslavers promoted Christianity as a tool of obedience, Africans reinterpreted its narratives to address their own conditions.23 Biblical stories of bondage, deliverance, and prophetic justice became meaningful precisely because they resonated with African modes of reading the world, in which suffering and redemption were part of a moral cosmos governed by both divine intention and spiritual agency.

Hoodoo, or conjure, emerged in the American South as a system of healing, protection, and practical ritual rooted in Central and West African spiritual technologies. Its practitioners drew upon knowledge of herbs, roots, and material objects that carried spiritual force, integrating these with Christian prayers, Psalms, and symbolic gestures.24 Hoodoo did not function as a separate religion but as a set of ritual practices addressing everyday needs: illness, conflict, safety, and justice. The incorporation of biblical texts reflected not a departure from African customs but the adaptation of Christian elements into older traditions of invoking spiritual power through spoken formulas and material media.

Conjure practitioners often held positions of quiet influence within enslaved communities. Their authority stemmed from African precedents in which diviners and healers mediated between spiritual and social order. In the American context, these figures reconfigured their roles by employing Christian symbols alongside African techniques, demonstrating continuity in the function of ritual specialists even as the content of their practices transformed.25 The flexibility of Hoodoo allowed it to survive the prohibitions of slaveholders, since its Christian components could be presented as legitimate forms of piety while its African elements remained embedded in private or hidden ritual contexts.

Vodou developed in the Caribbean, most notably Haiti, and in Louisiana, where Catholic iconography intersected with African spirit veneration to form a religious structure grounded in ritual possession, ancestral reverence, and ceremonial order.26 In these regions, Catholic saints became visual and devotional stand-ins for African deities, enabling practitioners to continue venerating Lwa within the framework of Catholic liturgy. The use of candles, holy water, images, and processions aligned closely with African ritual aesthetics, making Catholicism particularly amenable to syncretic reinterpretation.

In Louisiana, Vodou adapted to the local environment by incorporating elements of both French Catholicism and African-derived healing traditions. Ritual leaders, including influential women known for their authority in spiritual matters, presided over ceremonies that combined African cosmology with Catholic devotional practices.27 These rituals affirmed communal identity and created networks of mutual support, offering both spiritual and social resources to people living under restrictive racial hierarchies. Vodou’s persistence in Louisiana reflected not only African cultural memory but also the capacity of syncretic traditions to evolve in response to local histories and political pressures.

Syncretism operated as a dynamic process rather than a fixed religious formula. Black Christianity, Hoodoo, and Vodou each illustrate how enslaved and free Africans used Christian materials without surrendering African worldview structures.28 By integrating Christian teachings into African frameworks, rather than the reverse, they preserved cultural coherence, created new paths for spiritual agency, and reshaped American religious life in ways that remain visible today. Syncretism thus became a strategy for adaptation, survival, and the assertion of meaning under conditions designed to suppress cultural expression.

Memory, Ancestors, and the Power of the Dead

African concepts of ancestry formed one of the most enduring continuities to survive the transition into the Americas. In many West and Central African societies, the dead remained active members of the community, shaping moral order and mediating the well-being of the living.29 This understanding of the sacred dead traveled with enslaved Africans, informing how they interpreted loss, preserved lineage, and constructed meaning amid forced displacement. Even when families were torn apart, ancestral frameworks provided a means of imagining continuity where social rupture was constant.

Within Christian settings, these ancestral sensibilities found new expression through the veneration of biblical figures, saints, and revered community elders. While Protestant traditions in North America did not emphasize saintly intercession, enslaved people often imbued biblical characters with a presence that mirrored African expectations of ancestral guidance.30 The stories of prophets, martyrs, and patriarchs became loci of spiritual authority not merely because they were scriptural exemplars but because they could be integrated into a layered spiritual genealogy that linked African cosmology with Christian narrative structure.

Burial practices also reflected the adaptation of African memory traditions within Christian frameworks. In both West Central Africa and the Americas, graves were treated as places of ongoing relationship rather than final separation. Enslaved Africans frequently buried personal objects, shells, pottery fragments, or symbolic items with the deceased, practices that scholars identify as continuities with Kongo funerary customs.31 These acts signaled belief in the ongoing influence of the dead and affirmed communal responsibility toward ancestors even in contexts where plantation owners sought to restrict ritual expression.

In African American churches, the moral authority of elders often derived from ancestral models of leadership, where age carried spiritual significance and familial wisdom was intertwined with ritual memory. Early Black congregations drew upon these sensibilities as they developed religious offices, mentorship structures, and communal responsibilities.32 The church became a site where ancestral frameworks were rearticulated through Christian teachings, enabling communities to reconstruct kinship bonds fractured by enslavement. This reinterpretation of authority helped stabilize communal life and offered a counterweight to the dislocations of slavery.

Music, testimony, and storytelling provided further avenues for sustaining ancestral presence. Spirituals and oral traditions did not merely recount biblical events; they connected listeners to a broader lineage of suffering, endurance, and hope that paralleled African patterns of invoking the past to guide the present.33 Through these practices, enslaved people cultivated a sense of belonging that extended beyond immediate family networks to encompass collective ancestry and shared memory. In this environment, the sacred dead continued to shape communal identity, ensuring that African understandings of continuity and moral obligation survived within the evolving religious landscape of the Americas.

Churches as Institutions of Autonomy, Leadership, and Resistance

As enslaved Africans began forming their own religious gatherings, the church emerged as one of the few spaces where communal authority could be exercised with some degree of independence. Even under surveillance, clandestine meetings, often referred to as the “invisible institution,” allowed participants to pray, preach, and interpret scripture outside the control of slaveholders.34 These gatherings constituted more than devotional practice; they created social structures in which Africans reorganized community life on their own terms. Leadership roles within these spaces, such as exhorters and class leaders, echoed African traditions in which ritual specialists held moral authority and guided communal well-being.

Formal Black congregations developed gradually as free and enslaved people established autonomous churches, particularly in urban areas where mobility was comparatively greater.35 These churches provided organizational frameworks that mirrored African expectations of collective responsibility, enabling congregants to pool resources, care for vulnerable members, and negotiate with outside authorities. They also cultivated networks that connected rural plantation communities with urban centers, facilitating the spread of religious ideas and strategies for communal resilience. Through these institutions, African Americans built parallel structures of governance that contrasted sharply with the coercive hierarchies imposed by slavery.

Within these religious environments, clergy and lay leaders became influential figures whose authority extended beyond spiritual matters. Ministers often served as teachers, counselors, and advocates, reinforcing the church’s role as a center for education and political guidance.36 Enslaved people drew upon African precedents in which spiritual leaders mediated between divine and human realms, interpreting their Christian responsibilities in ways that paralleled earlier models of ritual leadership. This continuity of function helped transform Christian leadership into a role infused with both spiritual and cultural authority.

Churches also became spaces for developing collective political consciousness. Although open resistance was dangerous, religious messages frequently carried coded critiques of slavery and visions of liberation drawn from biblical narratives.37 Enslaved preachers and congregants used the stories of Exodus, Daniel, Jonah, and the prophets to imagine divine sanction for deliverance, shaping a political theology rooted in African interpretive strategies. Religious gatherings offered both spiritual encouragement and a vocabulary for expressing dissatisfaction with bondage, creating a fertile environment for the articulation of collective grievances.

In some cases, religious institutions provided the ideological foundation for organized resistance. Leaders such as Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner interpreted scripture through lenses informed by African cosmologies, transforming biblical narratives into calls for direct action.38 While not representative of all enslaved Christians, these movements illustrated how African Americans could use religious authority to challenge the system that attempted to control them. Even where uprisings did not occur, the church fostered political agency by affirming the moral worth of the enslaved and sustaining communal networks capable of resisting dehumanization. Through these mechanisms, Black religious institutions became critical venues for spiritual, social, and political self-determination.

Cultural Resistance: Spirituals, Codes, and Revolutionary Meaning-Making

Music and narrative expression became essential tools through which enslaved Africans reshaped Christian teachings into languages of resistance. Spirituals, rooted in both African musical aesthetics and biblical themes, offered a flexible medium for expressing longing, grief, endurance, and hope.39 Their melodic structures often reflected African tonal sensibilities, while their lyrics reinterpreted Christian stories through the lived realities of bondage. Spirituals did more than express religious devotion; they created a shared emotional landscape that helped communities endure the traumas of enslavement.

The use of biblical narratives as encoded commentary constituted another powerful form of cultural resistance. Figures such as Moses, Joshua, and Daniel appeared frequently in enslaved religious expression because their stories resonated with African frameworks for understanding suffering and deliverance.40 The Exodus narrative in particular provided a theological vocabulary that could critique slavery while remaining outwardly consistent with Christian doctrine. These biblical stories became metaphors through which enslaved people articulated visions of liberation and divine justice, interpretations shaped as much by African cosmologies as by missionary instruction.

Performance practices embedded additional layers of meaning. Call-and-response patterns, improvisation, and rhythmic variation (central features of African musical traditions) allowed performers to introduce subtle shifts in tone or emphasis that communicated coded messages to those able to interpret them.41 These communal performances created spaces where African Americans could express defiance safely, masking political messages within the acceptable framework of worship. The adaptability of these practices made them effective tools for circulating ideas about escape, solidarity, and spiritual resilience.

Some spirituals carried specific coded instructions related to flight and resistance. While the extent of this practice varied by region and circumstance, certain songs used geographical references, metaphors of crossing water, or invocations of spiritual guidance to signal opportunities for escape or preparations for collective action.42 Even when not used explicitly for communication, the thematic emphasis on freedom, movement, and divine support helped sustain mental and emotional resistance. These coded elements reflected a broader African tradition of layered meaning in oral performance, where audiences were expected to interpret content according to social context.

Testimony and storytelling further supported cultural resistance by preserving communal memory and reinforcing shared values. Enslaved preachers and elders often adapted Christian lessons to address issues of injustice, moral endurance, and collective identity.43 Their sermons and narratives echoed African practices in which oral tradition conveyed history, ethics, and spiritual authority. In recontextualizing Christian teachings through African interpretive strategies, enslaved communities produced a dynamic religious discourse that both affirmed their humanity and critiqued the social order.

These practices demonstrate how African Americans used Christian materials not simply to survive but to create cultural systems that challenged the spiritual legitimacy of slavery. The blending of African aesthetics with biblical narratives produced a religious language capable of sustaining resistance, articulating hope, and envisioning a future beyond bondage.44 Through song, performance, testimony, and coded symbolism, cultural resistance became an essential means of asserting identity and agency in a world designed to suppress both.

Conclusion: Syncretism as Creativity, Resistance, and Cultural Rebirth

The encounter between African religions and Christianity in the Americas produced spiritual systems that were neither simple adaptations nor imitations. Instead, they represented acts of cultural creativity grounded in the determination to preserve coherence in a world built on rupture. African cosmologies provided enslaved people with interpretive tools for reconstructing identity, community, and meaning under the harshest conditions. By drawing upon familiar structures of divine mediation, ancestral presence, and ritual practice, they reshaped Christian teachings into forms that affirmed their humanity and sustained their emotional and spiritual lives.45 These transformations were not marginal; they became central to the development of African American religious culture.

Syncretism also served as a vehicle for political imagination and resistance. Through reinterpretations of biblical stories, the incorporation of African ritual aesthetics, and the formation of independent religious spaces, enslaved Africans produced theological visions that challenged the moral foundations of slavery.46 The creation of Black churches, the authority of spiritual leaders, and the circulation of coded religious expression provided avenues for critiquing oppression while nurturing collective aspirations for liberation. These practices demonstrated how religious creativity could undermine systems of domination even without overt rebellion.

Over time, the syncretic traditions forged in bondage reshaped the broader religious landscape of the United States and the Caribbean. Black Christianity, Hoodoo, and Vodou became enduring expressions of African heritage, each evolving within its own historical and regional context.47 Their persistence reflects the adaptability of African religious logics and the capacity of enslaved people to generate meaning from imposed structures. These traditions not only preserved cultural memory but also offered frameworks for negotiating new social realities in the aftermath of emancipation and into the present.

The history of African American religion thus reveals how cultural survival depends not solely on the preservation of old forms but on the ability to reinterpret and transform them. Syncretism made this possible by enabling enslaved Africans to engage Christianity without surrendering their worldview.48 The spiritual systems that emerged from this process testify to the resilience, ingenuity, and moral agency of communities who refused to let forced conversion erase their past. In their hands, religion became a means of enduring, resisting, and imagining futures beyond bondage—a legacy that continues to shape American religious life today.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

- John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972); Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Sylvia R. Frey and Betty Wood, Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

- Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

- Sterling Stuckey, Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

- Jacob K. Olupona, African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Wyatt MacGaffey, Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

- John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (London: Heinemann, 1969).

- Kongo healing and nganga practices discussed in MacGaffey, Religion and Society in Central Africa.

- Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Vintage, 1983).

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Yvonne P. Chireau, Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

- Mechal Sobel, Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro-Baptist Faith (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979).

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Thompson, Flash of the Spirit.

- Stuckey, Slave Culture.

- Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness.

- John W. Roberts, From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989).

- Dena J. Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977).

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Chireau, Black Magic.

- Sobel, Trabelin’ On.

- Karen McCarthy Brown, Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

- Newbell Niles Puckett, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926).

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy.

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Thompson, Flash of the Spirit.

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness.

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Bettye Collier-Thomas, Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion (New York: Knopf, 2010).

- Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness.

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Kenneth S. Greenberg, Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals.

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

- Levine, Black Culture and Black Conscioussciousness.

- Stuckey, Slave Culture.

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Thompson, Flash of the Spirit.

- Olupona, African Religions.

- Frey and Wood, Come Shouting to Zion.

- Chireau, Black Magic.

- Raboteau, Slave Religion.

Bibliography

- Blassingame, John W. The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

- Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Chireau, Yvonne P. Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Collier-Thomas, Bettye. Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion. New York: Knopf, 2010.

- Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

- Frey, Sylvia R., and Betty Wood. Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Greenberg, Kenneth S. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Levine, Lawrence W. Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt. Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Mbiti, John. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann, 1969.

- Olupona, Jacob K. African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Puckett, Newbell Niles. Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926.

- Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Roberts, John W. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

- Sobel, Mechal. Trabelin’ On: The Slave Journey to an Afro-Baptist Faith. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Stuckey, Sterling. Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Vintage, 1983.

- Thornton, John. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.