The Church’s persecution of dissent, extraction of wealth, control of knowledge, and insulation of clerical privilege were not isolated abuses but interlocking components of a coherent system.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power, Faith, and the Medieval Moral Universe

In medieval Europe, religious belief was not a private matter of conscience but the organizing framework of social, political, and moral life. The Roman Catholic Church stood at the center of this framework, exercising authority that extended far beyond theology into law, economics, education, and governance. As far as we know, there was no meaningful separation between sacred and secular power across much of medieval Christendom. Kings ruled by divine sanction, bishops governed territories, and canon law functioned alongside or above secular law, shaping everyday conduct from marriage and inheritance to labor obligations and punishment.1 Faith was not merely believed; it was enforced.

To describe this system as possessing dystopian elements is not to deny the sincerity of belief or the cultural coherence it provided, but to analyze how power operated within a sacralized order. A dystopian society, in analytical terms, is one in which authority becomes totalizing, dissent is criminalized, and fear is normalized as a tool of governance. Medieval Europe, under the institutional dominance of the Church, exhibits these characteristics with striking clarity. The Church claimed jurisdiction not only over bodies but over souls, asserting the authority to define sin, determine salvation, and mediate the afterlife. This claim transformed obedience into a moral necessity and resistance into eternal risk, collapsing the boundary between civic disobedience and spiritual ruin.2

Fear played a central role in sustaining this order. The doctrines of hell, purgatory, and eternal damnation were not abstract theological concepts but lived realities reinforced through sermons, art, ritual, and law. Excommunication carried consequences that extended beyond religious exclusion to social death, stripping individuals of legal protection and communal belonging. The power to condemn a soul was inseparable from the power to discipline a body, creating a system in which internal belief and external conformity were mutually reinforcing. Medieval theologians defended this arrangement as necessary for moral order, yet its practical effect was the internalization of surveillance, as individuals learned to police their own thoughts and actions in anticipation of divine judgment.3

This system proved especially hostile to dissent. Those who questioned doctrine or authority were labeled heretics, a category that fused intellectual disagreement with existential threat. Heresy was not treated as error but as contagion, justifying imprisonment, torture, and execution as acts of purification. The spectacle of punishment served not only to eliminate dissenters but to instruct the broader population in the consequences of deviation. Violence, sanctified by religious authority, became a pedagogical tool.4 The result was a moral universe in which conformity was framed as virtue and coercion as care.

Economically, the Church’s authority was reinforced through compulsory extraction. The tithe, typically set at one-tenth of agricultural production, functioned as a mandatory tax levied on largely impoverished populations, regardless of harvest conditions or personal hardship. While Christian doctrine emphasized humility and charity, ecclesiastical institutions accumulated vast landholdings and wealth, and high-ranking clergy often lived in comfort or opulence. This disparity did not go unnoticed by contemporaries, yet the sacred framing of obligation limited resistance, rendering economic exploitation a matter of spiritual duty rather than political choice.5

This essay argues that the medieval Roman Catholic Church, as an institution of power, produced social conditions that can be understood as dystopian in structure if not in intent. Through the fusion of law and belief, the use of fear as governance, the persecution of dissent, and the extraction of wealth, the Church constructed a moral universe in which obedience was enforced both externally and internally. Recognizing these dynamics does not require rejecting medieval faith or reducing the period to caricature. It requires examining how unquestionable moral authority, when paired with institutional power, can transform belief into a mechanism of control, offering a historical warning that remains relevant wherever faith and force converge.6

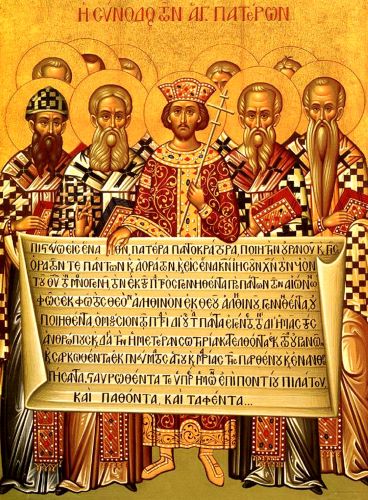

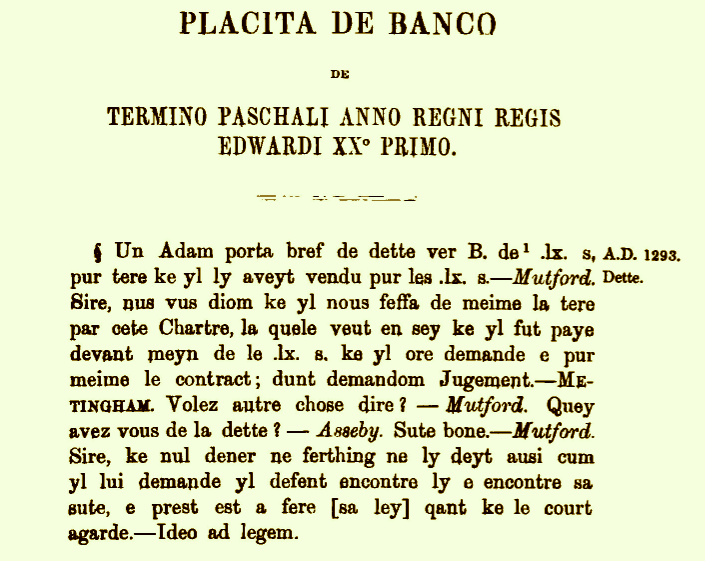

The Absence of Church–State Separation

In medieval Europe, political authority was inseparable from religious legitimacy. Secular rulers did not merely coexist with the Church but derived their right to govern from it. Kings were crowned through sacred ritual, oaths were sworn on relics and scripture, and law was understood as an extension of divine will rather than a product of popular consent. As far as we know, this sacralization of power was not symbolic alone. Canon law operated alongside, and often above, secular law, asserting jurisdiction over marriage, inheritance, moral conduct, and even aspects of criminal justice.7 The result was a political order in which obedience to the state was framed as obedience to God.

This fusion of authority was institutional as well as ideological. Bishops and abbots frequently acted as territorial lords, exercising judicial and economic control over vast lands. Ecclesiastical courts adjudicated cases involving clergy and laity alike, often superseding royal courts in matters deemed spiritual or moral. Conflicts between popes and kings were not struggles for separation but disputes over supremacy within a shared framework that assumed religious authority as foundational.8 Even when monarchs resisted papal claims, they rarely challenged the underlying premise that legitimate power was divinely sanctioned.9

The legal consequences of this arrangement were profound. Canon law treated moral offenses as legal violations, collapsing the distinction between sin and crime. Acts such as adultery, blasphemy, or deviation from doctrinal norms could carry both spiritual penalties and material consequences. Excommunication, in particular, functioned as a powerful hybrid sanction, severing individuals from religious life while simultaneously stripping them of legal protections and social standing.10 To be cut off from the Church was to be cut off from the community itself, demonstrating how legal and spiritual authority reinforced one another within a single coercive system.

The absence of church–state separation also meant that dissent lacked any protected space in which to exist. There was no neutral civic sphere where alternative beliefs could be expressed without theological consequence. Challenges to ecclesiastical authority were treated not as political disagreement but as existential threats to cosmic order. This dynamic laid the groundwork for systematic persecution, as deviation from orthodoxy was equated with treason against both God and society.11 In such a world, power did not merely rule bodies through law. It governed consciences, rendering resistance not only illegal but morally unthinkable.12

Canon Law and the Regulation of Everyday Life

Canon law functioned as a comprehensive regulatory system that extended far beyond matters of worship or doctrine. It governed marriage, inheritance, sexuality, labor obligations, and moral conduct, embedding ecclesiastical authority into the rhythms of daily life. As far as we know, these legal norms were not peripheral but central to medieval governance, shaping how people formed families, resolved disputes, and understood obligation. The law was presented not as negotiable or contingent, but as divinely ordained, rendering compliance a matter of salvation rather than civic duty.13 Everyday behavior was thus absorbed into a legal-moral framework that left little room for personal discretion.

Marriage offers a particularly clear example of this intrusion. Canon law defined marriage as a sacrament, placing it firmly under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and removing it from familial or communal control. Rules governing consent, legitimacy, adultery, and divorce were enforced through church courts, often with severe consequences for those who deviated from prescribed norms. These regulations reached into private life, transforming intimate relationships into sites of surveillance and discipline. Violations were framed not merely as social transgressions but as spiritual offenses with eternal implications.14 The household itself became an extension of ecclesiastical order.

Sexuality and bodily conduct were similarly regulated. Canon law classified a wide range of behaviors as sinful and subject to punishment, including actions that posed no threat to public order. Confession operated as a key mechanism in this system, compelling individuals to disclose private thoughts and acts under threat of spiritual consequence. This practice effectively transformed conscience into a regulated space, aligning internal belief with external obedience. The boundary between voluntary repentance and coerced self-policing was often indistinct, as fear of damnation incentivized constant self-surveillance.15 Control was exercised not only through courts, but through the interiorization of authority.

Time itself fell under ecclesiastical control. The liturgical calendar structured the year through holy days, fasts, and periods of obligatory observance, dictating when work could be performed and when abstention was required. These temporal regulations reinforced collective conformity while limiting economic and social autonomy. Participation was compulsory, and deviation could attract both spiritual penalties and social suspicion. By regulating time, the Church ensured that its authority was experienced not episodically but continuously, woven into the fabric of ordinary existence.16

Taken together, these legal mechanisms produced a society in which everyday life was saturated with obligation. Canon law did not merely respond to disorder; it preempted it by defining acceptable behavior in exhaustive detail. The result was a moral-legal environment in which freedom of action was constrained by fear of both earthly sanction and eternal consequence. This fusion of law and belief transformed routine activities into acts of compliance, revealing how regulation of the ordinary can serve as one of the most effective instruments of social control.17

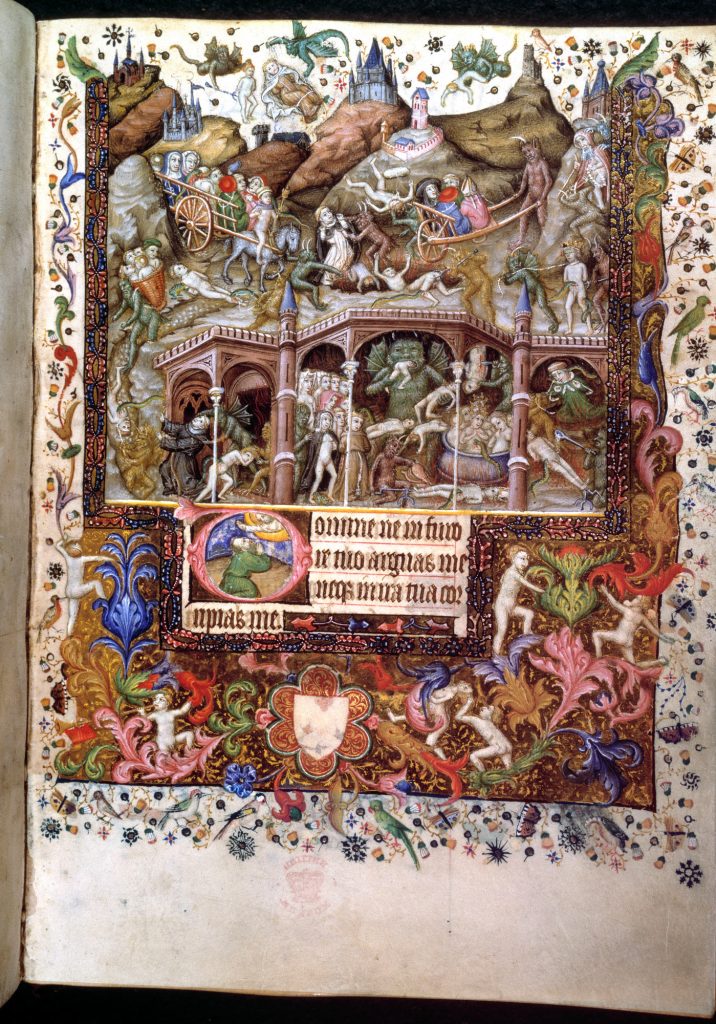

Fear as Governance: Sin, Damnation, and Obedience

Fear was not an incidental byproduct of medieval Christianity but a central mechanism through which authority was exercised and maintained. The Church’s teachings on sin, judgment, and the afterlife framed human existence as a continuous moral trial, in which every action carried eternal consequences. As far as we know, the fear of damnation was deeply embedded in popular consciousness, reinforced through sermons, confession, visual art, and ritual practice.18 Governance operated not primarily through constant physical force, but through the cultivation of internal anxiety, ensuring that obedience persisted even in the absence of direct supervision.

The doctrine of hell played a particularly powerful role in this system. Hell was presented not as a distant abstraction but as a vividly imagined destination, populated with graphic torments designed to instill dread. Church art, mystery plays, and preaching emphasized punishment over mercy, especially for ordinary believers. These representations functioned pedagogically, teaching fear as a moral reflex. The threat of eternal suffering transformed compliance into self-preservation, aligning religious devotion with psychological survival.19 Fear thus became habitual, shaping behavior long before any formal accusation or legal proceeding occurred.

Purgatory further intensified this dynamic by extending punishment beyond death even for the faithful. The uncertainty surrounding the duration and severity of purgatorial suffering reinforced dependence on ecclesiastical mediation. Prayers, indulgences, and masses offered pathways to relief, but only through Church-sanctioned channels. This structure ensured that spiritual anxiety translated into institutional reliance, binding believers to clerical authority at every stage of existence and beyond.20 Obedience was not only rewarded; it was marketed as mitigation of suffering.

Excommunication represented the convergence of spiritual terror and social control. To be cast out of the Church was to lose access to sacraments essential for salvation, but it also carried immediate worldly consequences. Excommunicated individuals were often denied legal standing, commercial interaction, and communal protection. The fear of exclusion functioned as a powerful deterrent, as isolation threatened both eternal fate and earthly survival.21 Through this mechanism, fear operated simultaneously on metaphysical and material levels, leaving little room for resistance.

Public punishment amplified these effects by transforming fear into spectacle. Trials for heresy, penance rituals, and executions were deliberately staged before large audiences, ensuring that discipline extended beyond the individual offender. The purpose was not merely retribution but instruction. Observers were meant to internalize the lesson that deviation carried catastrophic consequences. Violence, framed as moral correction, normalized cruelty while reinforcing conformity.22 Fear was thus socially distributed, teaching obedience through collective witnessing.

Over time, this system produced a population trained to regulate itself. Confession required individuals to scrutinize their own thoughts and desires, anticipating judgment before it was imposed. The result was an internalized form of governance in which authority resided not only in institutions but within the conscience itself. This internal surveillance reduced the need for constant coercion, as fear performed the work of discipline autonomously.23 In this sense, the Church’s use of fear represents one of the most effective and enduring models of governance in medieval Europe, demonstrating how control over belief can shape behavior more deeply than force alone.

Heresy, Dissent, and the Policing of Belief

In a sacralized political order, dissent could not be tolerated as mere disagreement. Heresy was defined not simply as incorrect belief but as a threat to cosmic and social stability. As far as we know, medieval authorities understood orthodoxy as essential to communal survival, meaning that deviation endangered not only individual souls but the moral health of society itself.24 This framing transformed belief into a matter of public security, legitimizing coercive intervention against those who challenged doctrine. Dissent thus ceased to be intellectual variance and became an act of existential defiance.

The definition of heresy was deliberately expansive and mutable. Doctrinal boundaries were policed by ecclesiastical authorities who retained exclusive power to determine orthodoxy, allowing belief itself to be criminalized retroactively. Teachings once tolerated could later be condemned, rendering past conformity irrelevant. This instability ensured caution and conformity, as uncertainty about acceptable belief heightened fear.25 The absence of fixed limits meant that safety lay not in understanding doctrine fully, but in unquestioning submission to authority as it evolved.

Institutionally, the policing of belief was formalized through inquisitorial systems that prioritized confession over evidence. Accusations of heresy often relied on rumor, denunciation, or coerced testimony, creating an environment in which suspicion spread easily and trust eroded. Procedures favored institutional preservation rather than truth-seeking, and the presumption of guilt placed the burden on the accused to demonstrate orthodoxy.26 Fear of denunciation encouraged silence, while public trials reinforced the lesson that belief itself was subject to surveillance.

Punishment for heresy was deliberately severe. Imprisonment, torture, and execution were justified as acts of purification rather than cruelty, framing violence as a necessary defense of truth. Public executions, particularly burning, served as ritualized warnings that fused spiritual cleansing with physical annihilation. The spectacle of punishment taught obedience through terror, embedding fear into communal memory.27 Violence against dissenters thus functioned as pedagogy, instructing the living through the destruction of the condemned.

The social consequences of heresy extended beyond formal punishment. Families of the accused could lose property, social standing, and legal protection, ensuring that fear radiated outward from the individual to the community. This collective vulnerability discouraged sympathy and resistance, isolating dissenters and reinforcing conformity. Heresy became socially contagious, not because of belief itself, but because association invited risk.28 The policing of belief therefore reshaped social relationships, privileging caution over solidarity.

Over time, this system produced a culture in which belief was disciplined before it could be articulated. Individuals learned to regulate speech, thought, and association preemptively, internalizing doctrinal boundaries as psychological constraints. The Church did not need to identify every dissenter; the possibility of accusation was sufficient.29 In this way, the persecution of heresy illustrates how control over belief can be achieved not only through force, but through the cultivation of fear, uncertainty, and self-censorship, rendering obedience both habitual and invisible.

Economic Extraction: Tithes, Tribute, and Inequality

Economic power was central to the Church’s authority in medieval Europe, binding material survival to spiritual obligation. The tithe, typically set at one-tenth of agricultural production, was not a voluntary donation but a compulsory levy enforced through ecclesiastical and secular mechanisms. As far as we know, refusal or failure to pay could result in spiritual penalties that carried real-world consequences, including social exclusion and legal vulnerability.30 This fusion of economic extraction and moral duty transformed taxation into an act of obedience, rendering resistance not merely unlawful but sinful.

For peasant communities, the burden of tithing was especially severe. Agricultural production was already precarious, subject to weather, disease, and local conflict, yet the tithe was demanded regardless of circumstance. Even in years of famine or crop failure, obligations remained fixed, reinforcing a system in which risk was borne disproportionately by the poor.31 The Church’s claim on surplus effectively insulated ecclesiastical institutions from economic volatility while intensifying hardship among those least able to absorb it. Economic inequality was thus not accidental but structurally embedded.

At the same time, the Church accumulated vast wealth through land ownership, rents, and additional fees tied to sacraments and burial practices. Monasteries, bishoprics, and cathedral chapters became major economic actors, often rivaling or surpassing secular lords in material resources. While Christian teaching emphasized humility and charity, high-ranking clergy frequently lived in comfort or luxury, a contradiction noted even by contemporaries.32 This disparity undermined claims of moral authority while reinforcing the perception that obedience flowed upward and resources flowed inward.

The sacred framing of economic obligation limited avenues for protest. Because tithes were presented as owed to God rather than to an institution, criticism risked spiritual condemnation. Economic dissent could thus be reclassified as impiety, discouraging collective resistance and isolating grievances.33 In this way, material inequality was stabilized through theological justification, demonstrating how economic extraction functioned not only as a fiscal practice but as a mechanism of social control. The tithe did more than fund the Church; it disciplined populations by tying subsistence to submission.34

Clerical Privilege and Institutional Immunity

Clerical authority in medieval Europe was reinforced not only through doctrine but through legal privilege. Members of the clergy occupied a distinct juridical category, subject primarily to ecclesiastical courts rather than secular law. As far as we know, this separation created a dual legal system in which ordinary people were bound by both canon and civil law, while clergy operated with significant insulation from secular accountability.35 This imbalance undermined the principle of equal justice and entrenched hierarchy as a structural feature of medieval governance.

Ecclesiastical immunity extended beyond legal jurisdiction to encompass economic and social protections. Clergy were often exempt from certain taxes, tolls, and military obligations that burdened the lay population. These privileges were justified through sacred function rather than public service, reinforcing the notion that spiritual authority entitled its holders to material exemption.36 Over time, such exemptions contributed to resentment among lay communities, particularly when clerical wealth and privilege contrasted sharply with widespread poverty and obligation.

Institutional protection also shielded misconduct. While ecclesiastical courts could, in theory, discipline clergy, enforcement was inconsistent and frequently lenient, especially for high-ranking officials. Charges of corruption, abuse, or negligence were often resolved internally, limiting transparency and accountability.37 This inward-facing system prioritized institutional reputation over justice, reinforcing the perception that clerical authority operated beyond meaningful constraint. The result was not merely individual abuse of power but systemic insulation from consequence.

These privileges had broader social effects. By placing clergy above ordinary legal processes, the Church reinforced a moral hierarchy that mirrored and justified social inequality. Authority flowed downward, accountability upward only in theory. Challenges to clerical privilege were therefore interpreted not as demands for justice but as threats to divine order itself.38 Institutional immunity thus functioned as a stabilizing mechanism, preserving ecclesiastical dominance by ensuring that those who wielded spiritual power remained largely beyond the reach of the systems that governed everyone else.

Knowledge, Literacy, and Control of Truth

Control over knowledge was one of the Church’s most effective instruments of authority in medieval Europe. Literacy was rare, formal education was limited, and access to written texts was tightly regulated through ecclesiastical institutions. As far as we know, the vast majority of the population encountered religious doctrine only through oral transmission, sermons, and visual imagery, all of which were mediated by clerical interpretation.39 This asymmetry ensured that theological meaning flowed in one direction, from institution to believer, with little opportunity for verification or challenge.

Language itself functioned as a gatekeeping mechanism. Scripture, theology, and canon law were preserved primarily in Latin, a language inaccessible to most laypeople. This linguistic barrier prevented independent engagement with sacred texts and reinforced clerical monopoly over interpretation. To question doctrine required not only courage but education, a resource controlled almost entirely by the Church.40 Knowledge was therefore stratified, with understanding concentrated among those already empowered to define orthodoxy.

Educational institutions further reinforced this imbalance. Monasteries, cathedral schools, and later universities operated under ecclesiastical oversight, shaping curricula around approved theological frameworks. While these institutions preserved learning, they also constrained intellectual inquiry within acceptable boundaries. Subjects that threatened doctrinal authority were discouraged or prohibited, ensuring that scholarship remained compatible with orthodoxy.41 The preservation of knowledge thus coexisted with its containment, limiting the emergence of alternative worldviews.

Scriptural access was similarly restricted. Vernacular translations of the Bible were often condemned or prohibited, based on the belief that unauthorized reading would invite misinterpretation and heresy. Possession of unapproved texts could itself become grounds for suspicion or prosecution.42 This restriction transformed interpretation into a privilege rather than a right, binding truth to institutional approval and rendering independent understanding dangerous.

Visual culture played a compensatory but controlled role. Church art, stained glass, and iconography conveyed theological messages to illiterate populations, but these representations were carefully curated to reinforce obedience, hierarchy, and fear. Scenes of judgment, damnation, and suffering were common, shaping moral imagination through repetition rather than debate.43 Knowledge was not absent; it was shaped, simplified, and disciplined to align belief with authority.

The cumulative effect of these practices was a closed epistemic system. Truth was not discovered through inquiry but received through sanctioned channels. Challenges to official teaching could be dismissed not on evidentiary grounds but as moral failures or spiritual corruption.44 By controlling who could read, what could be read, and how meaning could be derived, the Church ensured that knowledge itself functioned as an instrument of governance. In such a system, ignorance was not merely tolerated; it was structurally advantageous, reinforcing obedience by limiting the conceptual tools required for dissent.45

Comparative Perspective: Medieval Church and Dystopian Control

When viewed comparatively, the medieval Roman Catholic Church exhibits structural features that recur across societies commonly identified as dystopian, despite vast differences in historical context and technology. Central among these features is the concentration of authority within a single institution that claimed moral, legal, and existential supremacy. As far as we know, dystopian systems do not depend on overt tyranny alone but on the normalization of power as inevitable and unquestionable. In medieval Europe, this normalization was achieved by framing authority as divinely ordained, rendering resistance not merely illegal but metaphysically incoherent.46 Control was sustained less by constant force than by the internalization of belief.

A defining characteristic of dystopian control is the fusion of ideology with governance. In such systems, dominant ideas are not presented as interpretations but as absolute truths. Medieval Christianity operated within this framework by presenting doctrine as immutable and universally binding. Divergence was not treated as error open to debate but as corruption requiring correction or elimination. This collapse of belief into law mirrors later dystopian models in which ideology replaces deliberation, ensuring that obedience appears natural rather than imposed.47 The result is a closed system in which alternative moral frameworks cannot gain legitimacy.

Another recurring feature is the erosion of private life. In dystopian societies, personal behavior becomes subject to scrutiny because it is understood to reflect ideological loyalty. Medieval practices of confession, moral regulation, and communal surveillance similarly reduced the boundary between public authority and private conscience. Individuals were encouraged to monitor not only their actions but their thoughts, anticipating judgment before it was rendered.48 This anticipatory compliance minimized the need for enforcement, as discipline became self-administered. The governance of interior life thus emerges as a key point of convergence between medieval and modern systems of control.

Fear functions comparably across dystopian systems, though its expression varies. In modern contexts, fear may be mediated through bureaucracy or technology. In medieval Europe, it was rooted in theology and ritual. The threat of eternal punishment, social exclusion, and public violence created an environment of uncertainty that discouraged dissent. Crucially, punishment was unpredictable enough to remain effective, reinforcing caution and conformity.49 Fear did not need to be constant; it needed only to be credible and inescapable.

What distinguishes the medieval Church within this comparative framework is the absence of technological mediation. Surveillance was not mechanical but social, moral, and psychological. Yet this absence does not weaken the comparison. It sharpens it. The Church demonstrates that dystopian control does not require advanced tools, only the alignment of belief, authority, and fear within a closed epistemic system.50 In this sense, the medieval Church stands as an early historical example of how totalizing power can operate effectively without modern instruments, offering a cautionary parallel for understanding dystopian dynamics across time.

Conclusion: Faith, Fear, and the Architecture of Obedience

The medieval Roman Catholic Church did not need to rely on constant physical coercion to maintain authority because its power was embedded within the moral architecture of society itself. Law, belief, and daily life were fused into a single system in which obedience appeared not as submission but as righteousness. As far as we know, this fusion allowed ecclesiastical authority to penetrate more deeply than secular rule alone ever could, shaping not only behavior but perception. The result was a social order in which compliance was sustained through internal conviction as much as external pressure, rendering resistance both dangerous and conceptually elusive.51

This system functioned most effectively because it transformed fear into a virtue. Fear of sin, fear of damnation, fear of exclusion, and fear of violence were not signs of oppression within medieval Christian culture but markers of moral awareness. Individuals were taught to interpret anxiety as evidence of spiritual seriousness, collapsing the distinction between ethical reflection and psychological control. Over time, this alignment normalized obedience by framing submission as care for the soul rather than capitulation to authority.52 In such a world, freedom was not denied outright; it was redefined so narrowly that it ceased to challenge power.

The Church’s persecution of dissent, extraction of wealth, control of knowledge, and insulation of clerical privilege were not isolated abuses but interlocking components of a coherent system. Each reinforced the others, ensuring that authority remained centralized and self-justifying. Economic obligation was sanctified, intellectual inquiry was constrained, and violence was moralized. Even acts of charity operated within this structure, mitigating suffering without altering its causes.53 The architecture of obedience thus proved remarkably durable, capable of absorbing criticism while preserving its foundational hierarchies.

To recognize the dystopian elements of medieval Church power is not to deny the sincerity of belief or the complexity of medieval life. It is to acknowledge how unquestionable moral authority, when coupled with institutional power, can produce conditions in which fear replaces consent and obedience substitutes for justice. As far as we know, societies that conflate salvation with submission risk mistaking order for legitimacy and stability for virtue. The medieval Church stands as a historical warning that systems built on fear may endure for centuries, but they do so at the cost of human autonomy, ethical plurality, and genuine freedom of conscience.54

Appendix

Footnotes

- Harold J. Berman, Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), 85–102.

- Brian Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), 12–18.

- R. I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987), 25–33.

- Edward Peters, Inquisition (New York: Free Press, 1988), 54–67.

- Jacques Le Goff, Medieval Civilization, 400–1500, trans. Julia Barrow (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988), 198–205.

- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 170–177.

- Berman, Law and Revolution, 85–92.

- Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 30–41.

- Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 193–201.

- Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 64–69.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 36–44.

- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 177–183.

- Berman, Law and Revolution, 85–102.

- James A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 229–247.

- John Bossy, Christianity in the West, 1400–1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 27–34.

- Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 1–15.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 52–60.

- Le Goff, Medieval Civilization, 145–154.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 32–41.

- Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 187–195.

- Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 74–80.

- Peters, Inquisition, 68–82.

- Peters, Inquisition, 92–101.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 66–75.

- Malcolm Lambert, Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 4–10.

- Peters, Inquisition, 68–82.

- Peters, Inquisition, 92–101.

- Lambert, Medieval Heresy, 186–193.

- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 195–203.

- Le Goff, Medieval Civilization, 198–205.

- Georges Duby, Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968), 44–52.

- R. H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (London: John Murray, 1926), 35–41.

- Lester K. Little, Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978), 66–72.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 92–99.

- Berman, Law and Revolution, 202–214.

- Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 88–94.

- John H. Mundy, Europe in the High Middle Ages, 1150–1309 (New York: Longman, 1991), 237–242.

- R. I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 101–108.

- Le Goff, Medieval Civilization, 53–61.

- Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 88–96.

- David C. Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 186–193.

- Margaret Aston, Faith and Fire: Popular and Unpopular Religion, 1350–1600 (London: Hambledon Press, 1993), 83–91.

- Jean-Claude Schmitt, The Holy Greyhound, trans. Martin Thom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 21–28.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 122–130.

- Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge, trans. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 131–133.

- Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951), 460–468.

- Foucault, Power/Knowledge, 131–133.

- Bossy, Christianity in the West, 27–34.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 130–138.

- James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 3–8.

- Berman, Law and Revolution, 292–298.

- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 201–208.

- The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 142–149.

- Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 468–474.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951.

- Aston, Margaret. Faith and Fire: Popular and Unpopular Religion, 1350–1600. London: Hambledon Press, 1993.

- Berman, Harold J. Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Bossy, John. Christianity in the West, 1400–1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Brundage, James A. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Duby, Georges. Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968.

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

- ———. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Translated by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Lambert, Malcolm. Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

- Le Goff, Jacques. Medieval Civilization, 400–1500. Translated by Julia Barrow. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

- ———. The Birth of Purgatory. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Lindberg, David C. The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Little, Lester K. Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Mundy, John H. Europe in the High Middle Ages, 1150–1309. New York: Longman, 1991.

- Peters, Edward. Inquisition. New York: Free Press, 1988.

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. The Holy Greyhound: Guinefort, Healer of Children since the Thirteenth Century. Translated by Martin Thom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Tawney, R. H. Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. London: John Murray, 1926.

- Tierney, Brian. The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.