Across four centuries, the violence inflicted on Native Americans by the United States reveals a consistent architecture rather than a sequence of unrelated episodes.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Violence as Policy, Not Tragedy

The history of the United States’ relationship with Native Americans has too often been framed as a series of tragic misunderstandings, regrettable excesses, or isolated eruptions of frontier brutality. Such narratives obscure the central reality that killing, forced removal, and kidnapping were not peripheral to state formation but integral to it. From the nation’s earliest years, violence against Indigenous peoples was repeatedly authorized, funded, and enforced by governmental institutions. It functioned as policy, not accident, and as governance, not breakdown.

Distinguishing between private violence and state violence is essential to understanding this history. While settler attacks and vigilante atrocities were real and devastating, they operated within a broader framework of federal law, military action, and administrative practice that enabled and often encouraged them. Treaties backed by coercion, military campaigns framed as pacification, and legislation facilitating removal all demonstrate that the federal government did not merely fail to prevent violence. It structured and sustained it. The line between civilian aggression and state power was frequently thin, porous, and intentionally blurred.

Killing was only one instrument in a broader repertoire of coercion. Forced marches, deliberate deprivation of food and resources, mass incarceration on reservations, and the systematic seizure of Native children all served the same end. These practices aimed to eliminate Indigenous presence as a political and territorial reality, whether through death, displacement, or cultural destruction. Kidnapping, particularly of children, was recast as reform. Starvation was framed as necessity. Removal was justified as progress. Each relied on the authority of the state to normalize acts that would otherwise be recognized as crimes.

To treat this history as tragedy alone is to mistake consequence for cause. Tragedy implies inevitability or misfortune. Policy implies choice, intent, and responsibility. This essay proceeds from the premise that U.S. violence against Native Americans was the product of deliberate decisions embedded in law, budgetary priorities, military doctrine, and administrative systems. Understanding that violence as policy is not an exercise in anachronistic judgment. It is a necessary step toward historical clarity about how power was exercised, how territory was secured, and how a nation was built through the systematic destruction of those who stood in its way.

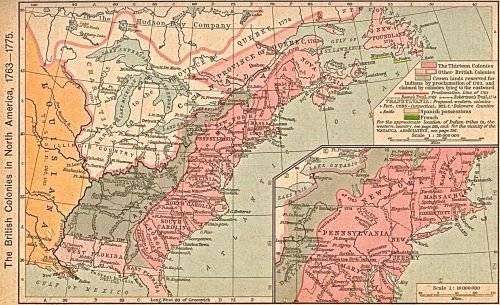

Colonial Inheritance and Revolutionary Continuity (1600s–1790s)

Long before the creation of the United States, European colonial regimes in North America developed systems of warfare and coercion aimed at eliminating Indigenous resistance to settlement. British colonial governments authorized punitive expeditions, sanctioned the taking of hostages, and in several colonies offered bounties for Native scalps. These practices were not spontaneous acts of frontier rage. They were organized, funded, and legitimated by colonial authorities who understood violence as a tool for securing land and disciplining populations deemed incompatible with colonial expansion.

Kidnapping and forced captivity accompanied killing from the outset. Native men, women, and children were seized as laborers, hostages, or leverage in negotiations. During periods of conflict, entire communities were targeted not merely for defeat but for removal from contested territory. Warfare blurred into extermination and enslavement, particularly in New England and the southern colonies. Colonial governments codified these practices through militia laws, bounty statutes, and treaties imposed under duress. Violence was embedded in governance, not confined to moments of breakdown.

The American Revolution did not disrupt this logic. Revolutionary leaders invoked liberty and self-determination while continuing, and in some cases intensifying, campaigns against Native nations. Indigenous communities were widely portrayed as obstacles to independence or as allies of imperial enemies, justifying preemptive attacks and land seizures. Continental and state forces conducted operations that destroyed villages, crops, and food stores, deliberately targeting civilian survival. The war for independence thus expanded the geographic scope of colonial violence rather than repudiating its methods.

When the United States emerged as a sovereign nation, it inherited both territory and technique. Revolutionary continuity lay not only in political institutions but in assumptions about Indigenous dispossession. The new republic absorbed colonial practices of removal, coercion, and killing into federal authority, translating imperial violence into republican policy. The language changed, but the structure endured. What had been colonial conquest became national expansion, carried forward by a government that treated Indigenous elimination as compatible with, and even necessary to, republican state building.

The Early Republic: Removal by Treaty, Force, and Starvation (1790s–1820s)

With the ratification of the Constitution, violence against Native Americans was absorbed into a formal framework of federal authority. The early republic did not abandon coercion in favor of law. It fused the two. Treaties became the primary legal instrument through which Indigenous land was transferred, yet these agreements were routinely negotiated under conditions of military threat, economic pressure, and political isolation. Consent was nominal, and refusal often invited force. Treaty making thus functioned less as diplomacy between sovereigns than as a mechanism for legitimizing dispossession already underway.

Federal military power played a decisive role in enforcing this system. The new government funded standing forces and frontier garrisons tasked explicitly with suppressing Native resistance to settlement. Campaigns against confederacies in the Ohio Valley and the Southeast targeted not only warriors but villages, crops, and food stores. Destruction of sustenance was a deliberate strategy. Starvation was deployed to compel submission, relocation, or treaty compliance. Violence extended beyond the battlefield into the material conditions of survival.

Congressional appropriations reveal the degree to which removal and coercion were institutional priorities. Funds were allocated for punitive expeditions, fort construction, and militia mobilization, embedding Indigenous displacement within the ordinary business of government. These expenditures were debated, approved, and renewed through legislative processes that treated Native resistance as a security problem rather than a political grievance. Budgetary support transformed episodic violence into sustained policy.

At the same time, federal officials articulated a paternalistic rhetoric that framed coercion as benevolence. Indigenous nations were described as dependents whose lands must be managed for their own good. Removal was presented as protection from settler encroachment, even as it enabled further expansion. When Native communities resisted, deprivation and force followed. Hunger, disease, and displacement were accepted outcomes of governance, not unintended side effects.

By the 1820s, the early republic had established a durable pattern. Treaties formalized land loss. Military force enforced compliance and starvation hastened submission. Together, these tools advanced territorial consolidation while preserving the appearance of legality. The state did not merely tolerate violence against Native Americans. It organized, funded, and justified it as an essential function of national development.

Jacksonian America and the Normalization of Ethnic Cleansing (1830s)

The 1830s marked the moment when removal hardened into a systematic, bureaucratized program of ethnic cleansing. What had previously been pursued through ad hoc treaties and regional military campaigns was now openly embraced as national policy. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 provided legislative authorization for the mass displacement of Indigenous nations east of the Mississippi River. Violence was no longer an auxiliary instrument. It was built directly into the machinery of governance.

Congressional debates surrounding removal reveal a striking candor about expected outcomes. Lawmakers acknowledged that displacement would cause suffering and death, yet framed these consequences as unavoidable costs of progress. Removal was justified as inevitable, humane, and even benevolent, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The language of necessity functioned to moralize coercion. By presenting forced migration as the only viable alternative to extinction, policymakers recast state violence as reluctant stewardship.

Military enforcement transformed removal from statute into lived reality. Federal troops and state militias compelled Native communities to abandon their lands, often under conditions of confinement and surveillance. Forced marches were conducted with minimal provision for food, shelter, or medical care. Disease and exposure followed predictably. Death was not incidental to these operations. It was a foreseeable and repeatedly documented consequence of policies executed with indifference to Indigenous survival.

The normalization of removal depended on administrative routinization. Contracts were issued, detention camps established, and logistical systems developed to manage human displacement at scale. Indigenous people were rendered as units to be transported rather than communities with political rights. This bureaucratic framing insulated policymakers from accountability by converting suffering into process. Once embedded in administrative practice, violence ceased to appear exceptional and became procedural.

Resistance did not alter this trajectory. Legal challenges, diplomatic appeals, and acts of collective defiance were met with intensified coercion. Supreme Court rulings recognizing Native sovereignty were ignored when they conflicted with executive and legislative priorities. Federal authority asserted itself not through adherence to law but through the control of armed force and resources. The removal regime thus demonstrated the limits of legal recognition in the face of state determination.

By the end of the decade, ethnic cleansing had been normalized as a legitimate function of American governance. Indigenous presence east of the Mississippi was no longer treated as a political problem to be negotiated, but as an obstacle to be eliminated. The Jacksonian period did not invent violence against Native Americans. It rationalized it, legalized it, and scaled it. In doing so, it established a model of state action in which mass displacement and death were accepted instruments of national expansion.

Western Expansion and the Era of Open Killing (1840s–1870s)

As the United States expanded westward in the mid nineteenth century, violence against Native Americans shifted from bureaucratized removal to overt, sustained killing. Territorial conquest brought federal troops, volunteer militias, and settler auxiliaries into direct conflict with Indigenous nations across the Plains, the Southwest, and the Pacific Coast. These campaigns were not aberrations on the margins of state power. They were financed by Congress, coordinated through the War Department, and justified as necessary to secure settlement and commerce. Killing became explicit policy rather than an implied consequence.

Nowhere was this more visible than in California following the gold rush. State and federal authorities funded militias that conducted campaigns of extermination against Native communities, often with little distinction between combatants and civilians. Massacres were reported, reimbursed, and normalized through official channels. Bounty systems rewarded killing, while federal officials framed these actions as pacification. The line between warfare and slaughter was erased by administrative endorsement and fiscal support.

On the Plains, U.S. Army campaigns targeted not only resistance but subsistence. Villages were destroyed, food supplies seized or burned, and winter campaigns pursued precisely because exposure would magnify suffering. These tactics were openly discussed in military correspondence and justified as efficient means of forcing surrender. Treaties followed devastation, not negotiation. Indigenous survival was subordinated to the strategic objective of clearing land for railroads, ranching, and settlement.

Civilian participation in violence further blurred accountability. Volunteer regiments and settler militias operated with federal authorization and reimbursement, allowing the state to outsource killing while retaining control. Atrocities committed by these forces were rarely punished. Instead, they were absorbed into a broader narrative of frontier necessity. The state’s role was not diminished by this delegation. It was concealed, rendering violence both deniable and routine.

By the 1870s, open killing had become a recognized phase of U.S. expansion. Removal and treaty making persisted, but only after military defeat and demographic collapse had weakened Indigenous resistance. The era of western expansion thus represents the culmination of earlier policies, not a departure from them. Killing was not an excess at the edge of empire. It was a central mechanism through which the United States transformed contested territory into national space.

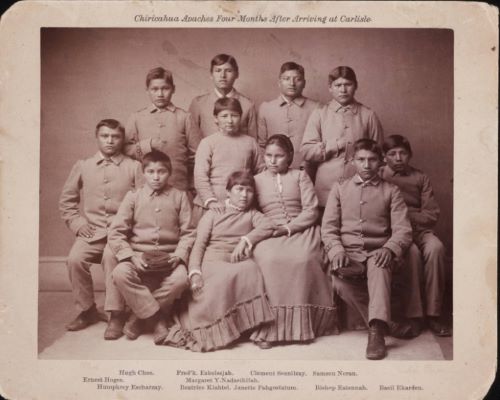

Kidnapping as Policy: Boarding Schools and Forced Assimilation (1870s–1930s)

By the late nineteenth century, overt military killing increasingly gave way to a different form of state violence: the systematic kidnapping of Native children. Federal policymakers framed this shift as humanitarian reform, but its coercive foundations were unmistakable. Boarding schools were designed not simply to educate, but to sever Indigenous children from their families, languages, religions, and social structures. Removal of children became a central mechanism through which the state pursued what military campaigns had not fully achieved: the destruction of Indigenous societies as living political and cultural entities.

This system relied on compulsion rather than consent. Federal agents, missionaries, and local authorities forcibly removed children from their communities, often under threat of withholding rations or prosecuting parents. Resistance was met with punishment, including incarceration of adults who refused to comply. The state asserted a custodial authority that treated Native families as unfit and Native cultures as obstacles to progress. Kidnapping was reframed as guardianship, masking violence beneath the language of care.

Boarding schools operated as carceral institutions. Children were transported long distances, confined under strict discipline, and subjected to physical punishment for speaking their languages or practicing their traditions. Disease, malnutrition, and abuse were endemic. Mortality rates were high, and burial grounds attached to schools testify to the lethal consequences of confinement. These outcomes were documented by officials yet tolerated as necessary sacrifices in the pursuit of assimilation.

Federal law and funding sustained this regime. Congress appropriated funds specifically for the construction and operation of boarding schools, embedding child removal within the federal budget. Administrative systems tracked attendance, enforced compliance, and coordinated transfers across jurisdictions. The machinery of assimilation functioned with bureaucratic precision, transforming the seizure of children into routine administrative practice rather than exceptional intervention.

The logic underlying boarding schools mirrored earlier forms of removal. Just as land had been taken to clear territory for settlement, children were taken to clear the future of Indigenous continuity. Policymakers explicitly articulated this goal, arguing that Indigenous identity must be eradicated within a generation. Cultural destruction was not collateral damage. It was the objective. Kidnapping thus served as a nonlethal extension of earlier eliminationist policies.

By the early twentieth century, the boarding school system stood as one of the most pervasive forms of state violence inflicted on Native Americans. Though less visibly brutal than massacres or forced marches, its effects were enduring. Generations of children were traumatized, families were fractured, and communities were destabilized. The shift from killing to kidnapping did not signal moral progress. It marked a transformation in technique, preserving the core objective of Indigenous elimination through state power exercised over the most vulnerable.

Reservation Regimes and Carceral Control (Late 19th–Early 20th Century)

As military conquest subsided, the United States consolidated its control over Native Americans through reservation regimes that functioned as systems of confinement. Reservations were not neutral spaces of protection, as federal rhetoric often claimed. They were instruments of containment designed to immobilize Indigenous populations, restrict movement, and enforce dependency. Geographic isolation replaced open warfare as the primary means of control, but the underlying objective remained unchanged. Indigenous autonomy was to be neutralized as a political force.

Federal authority on reservations was enforced through a dense web of surveillance and coercion. Bureau of Indian Affairs agents exercised broad discretionary power over daily life, including movement, labor, food distribution, and family structure. Rations became tools of compliance. Those who resisted federal directives risked starvation or imprisonment. The reservation thus operated as a carceral space in which survival itself was conditional on obedience to state authority.

Military force did not disappear from this system. Troops were frequently deployed to suppress resistance, enforce arrests, and police religious and cultural practices. Ceremonies such as the Sun Dance were criminalized, and Indigenous leaders were detained or exiled for defiance. The boundary between civil administration and military occupation was deliberately blurred. Reservations were governed not through consent but through constant threat.

Legal mechanisms reinforced this coercive order. Federal courts denied Native nations meaningful jurisdiction over their own affairs, while extending federal criminal authority into reservation life. Acts of self-governance were reframed as disorder. The criminalization of Indigenous practices transformed cultural survival into legal liability. Killing was replaced by slow, structural violence that eroded community life over time.

By the early twentieth century, the reservation regime had become a normalized feature of American governance. It relied less on spectacle and more on routine deprivation, surveillance, and control. Death rates declined compared to earlier eras, but the conditions imposed were still lethal in their cumulative effects. Carceral control achieved what open violence had not. It rendered Indigenous resistance administratively manageable and politically invisible, embedding domination within the ordinary operations of the state.

Twentieth-Century Continuities: Policing, Sterilization, and Disappearance

The twentieth century is often portrayed as a period of reform in federal Indian policy, marked by the end of open warfare and the gradual recognition of Native rights. Yet beneath this narrative of progress, coercive state practices persisted in altered forms. Killing and forced removal gave way to policing, medical control, and bureaucratic disappearance. Violence did not end. It was reorganized, rendered less visible, and embedded within institutions that claimed to act in the name of welfare, health, and public order.

Policing became a primary mechanism through which federal and state authority asserted control over Native communities. Jurisdictional confusion between tribal, federal, and state law enforcement created conditions of chronic vulnerability. Crimes against Native people were frequently under investigated or ignored, while Native individuals were disproportionately targeted for arrest and incarceration. This imbalance was not accidental. It reflected a long standing pattern in which Indigenous lives were treated as administratively expendable, subject to control without reciprocal protection.

Medical violence represented another continuity of state coercion. During the mid twentieth century, federal health programs subjected Native women to forced or coerced sterilization, often without informed consent. These procedures were justified through paternalistic assumptions about poverty, dependency, and fitness for reproduction. The state again asserted authority over Indigenous bodies, this time through clinical rather than military means. Reproductive capacity was treated as a problem to be managed, echoing earlier efforts to eliminate Indigenous futures by other methods.

Disappearance also took institutional form. Native children continued to be removed from their families through adoption and foster care systems that framed separation as rescue. These practices replicated the logic of boarding schools while dispersing children into non Native households, severing cultural and familial ties. Disappearance here did not require physical death. It operated through administrative erasure, dissolving Indigenous identity across generations under the authority of courts and social service agencies.

These practices demonstrate that the twentieth century did not mark a clean break from earlier eras of violence. It marked a transformation in technique. The U.S. government no longer relied primarily on mass killing or forced marches, but it continued to exercise power through policing, medical intervention, and bureaucratic control. Violence persisted as policy, reshaped to fit a modern administrative state that could claim reform while sustaining domination in quieter, but no less destructive, forms.

Legal Reckoning and Persistent Impunity

As overt forms of violence receded from public view, legal discourse increasingly positioned itself as the arena in which historical wrongs might be addressed. Courts acknowledged aspects of Indigenous sovereignty, treaty obligations, and federal trust responsibility, yet these recognitions rarely translated into meaningful accountability for past or ongoing harm. Legal reckoning remained partial and constrained, shaped by doctrines that prioritized state stability over justice. The law became a site where violence was narrated, categorized, and ultimately contained rather than fully confronted.

Supreme Court jurisprudence illustrates this tension. While some decisions affirmed limited tribal authority, others entrenched federal plenary power, insulating the government from liability. Doctrines limiting standing, sovereign immunity, and jurisdictional reach restricted the capacity of Native nations to seek redress. Even when violations were acknowledged, remedies were narrow and procedural. The legal system recognized injury while simultaneously foreclosing accountability, producing a form of acknowledgment without consequence.

This pattern extended beyond the courts into administrative and legislative responses. Investigations into boarding schools, sterilization practices, and treaty violations generated reports and expressions of regret, but rarely resulted in prosecutions or comprehensive reparations. Responsibility was diffused across agencies and eras, allowing harm to be treated as historical residue rather than as the product of continuous policy. Impunity persisted not because evidence was lacking, but because legal and political systems were structured to absorb critique without altering power relations.

The persistence of impunity reveals the limits of legalism as a response to state violence. Law has functioned less as a corrective than as a boundary, defining what can be acknowledged without threatening institutional legitimacy. In this sense, legal reckoning has served to close the historical record rather than to reopen it. The absence of sustained accountability is not a failure of memory. It is a consequence of a system designed to recognize injustice while preserving the authority that produced it.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Dispossession

Across four centuries, the violence inflicted on Native Americans by the United States reveals a consistent architecture rather than a sequence of unrelated episodes. Killing, forced removal, and kidnapping did not arise from breakdowns of authority or failures of governance. They were instruments through which authority was exercised. As circumstances changed, techniques shifted. Open warfare gave way to bureaucratized removal. Removal yielded to confinement. Confinement was followed by assimilation, policing, and administrative disappearance. Each phase preserved the same core objective: the elimination of Indigenous peoples as autonomous political and territorial actors.

What distinguishes this history is not only the scale of harm, but its routinization. Violence was embedded in law, funded through appropriations, and administered by agencies that treated Indigenous survival as a problem to be managed. The state did not merely permit atrocities. It organized them through treaties signed under duress, military campaigns framed as pacification, schools justified as reform, and medical programs presented as care. The normalization of these practices allowed destruction to proceed without constant spectacle, transforming extraordinary harm into ordinary governance.

Understanding dispossession as architecture rather than tragedy alters the moral and analytical stakes of history. Tragedy invites mourning. Architecture demands accountability. It forces recognition that institutions, not just individuals, produced outcomes that were predictable and repeatedly accepted. The endurance of this system depended on its ability to rebrand violence without abandoning it, to substitute restraint for killing and bureaucracy for brutality while maintaining control over Indigenous lives and futures.

The implications of this history are not confined to the past. The structures that enabled killing and kidnapping continue to shape jurisdiction, policing, health care, child welfare, and land governance in Native communities. Historical clarity is therefore not an academic exercise alone. It is a prerequisite for justice. Until the United States confronts the architecture of dispossession as policy rather than misfortune, reckoning will remain symbolic, and impunity will remain the rule rather than the exception.

Bibliography

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995.

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000.

- Annals of Congress, selected debates on Indian affairs, 1790s–1820s.

- Biolsi, Thomas. Organizing the Lakota: The Political Economy of the New Deal on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992.

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Deloria, Vine Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

- Delucia, Christine. “Revisiting Indigenous ‘Encounters’ with Colonialism, Past and Present.” The American Historian 1 (2026).

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

- Lawrence, Jane. “The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women.” American Indian Quarterly 24, no. 3 (2000): 400–419.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina, and Teresa L. McCarty. To Remain an Indian: Lessons in Democracy from a Century of Native American Education. New York: Teachers College Press, 2006.

- Madley, Benjamin. An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

- Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. New York: Viking, 2007.

- Prucha, Francis Paul. American Indian Policy in the Formative Years: The Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, 1790–1834. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Satz, Ronald N. American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974.

- Taylor, Alan. American Colonies: The Settling of North America. New York: Penguin, 2016.

- U.S. Congress. Legislative history of the Indian Child Welfare Act, 1978.

- U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8.

- U.S. Senate. Indian Health Service: Investigations of Sterilization Practices. Selected hearings, 1970s.

- Utley, Robert M. The Indian Frontier of the American West, 1846–1890. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

- Wilkins, David E., and K. Tsianina Lomawaima. Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

- Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.13.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.