Greek political theory converged on a stark conclusion: republican government ends not when laws disappear, but when force ceases to belong to the community.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Security as a Political Argument

In the political imagination of ancient Greece, security was never a neutral concept. It was a language of urgency, a claim about danger, and a justification for exceptional action. Greek writers understood that appeals to protection often preceded the concentration of power, not its restraint. Tyranny, in this tradition, did not announce itself through the abolition of law, but through the redefinition of threat. When fear could be personalized, authority could be as well.

This insight emerged from lived experience rather than abstract theory. Greek poleis were less haunted by foreign conquest than by internal collapse. Civil strife, factional violence, and elite rivalry posed the most immediate dangers to communal survival. In such conditions, arguments for extraordinary protection carried persuasive force. The promise to restore order, suppress disorder, and protect the community from itself proved politically potent precisely because it addressed real anxieties.

Yet Greek thinkers were acutely aware of the paradox this logic created. Security required force, but force required control. The decisive question was not whether a city possessed armed power, but to whom that power answered. Once protection was detached from civic accountability and attached to an individual’s will, the balance of self-rule shifted irreversibly. The laws might remain, assemblies might still meet, but political freedom would already be compromised.

What follows examines that dynamic through one of its earliest and most instructive examples: the Athenian experience with personal security as a pathway to tyranny. By tracing how emergency protection evolved into personal domination, it argues that Greek political theory identified a structural danger that transcends historical context. When security becomes a personal mandate rather than a civic function, republican government ends not with spectacle, but with consent.

Order, Stasis, and the Fear of Internal Collapse

For Greek poleis, the gravest danger was not invasion from abroad but collapse from within. The concept of stasis, commonly translated as civil strife or factional conflict, haunted Greek political thought and practice. Stasis described more than disagreement. It signified the breakdown of shared norms, the hardening of factions, and the moment when citizens ceased to recognize one another as members of the same political community. Greek writers treated it as a recurring pathology rather than an aberration.

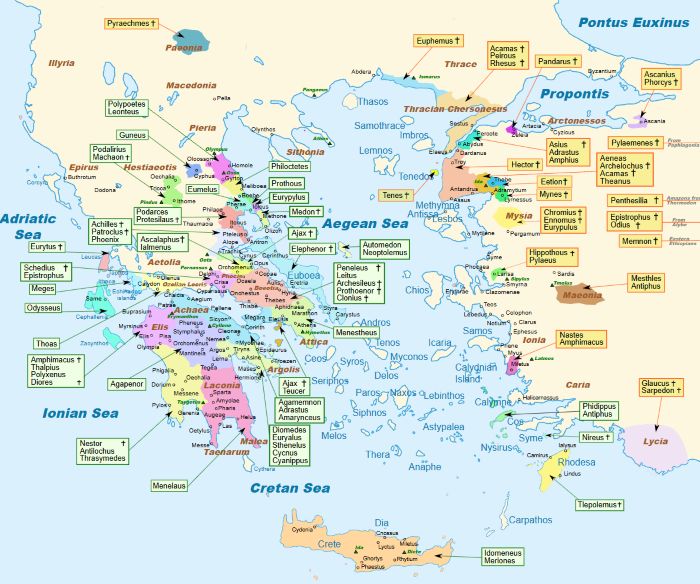

This fear was grounded in experience. Archaic and classical cities repeatedly oscillated between oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny, often through cycles of revenge and counter-revenge. Political competition easily became existential, particularly in societies without standing bureaucracies or professional enforcement mechanisms. When order collapsed, it did so rapidly. Property was seized, laws were ignored, and violence spread through personal networks rather than formal institutions. Stability, once lost, proved difficult to recover.

Because stasis threatened the very existence of the polis, appeals to order carried extraordinary moral weight. Leaders who claimed the ability to suppress faction and restore calm could plausibly present themselves as guardians of the common good. The argument was not framed as domination, but as rescue. Exceptional authority appeared justified when the alternative was civic disintegration. This made the language of security especially persuasive in moments of polarization.

Yet Greek observers were deeply ambivalent about this logic. While acknowledging the dangers of disorder, they also recognized that fear could be manipulated. The claim that internal enemies endangered the city was difficult to disprove and easy to expand. Once dissent was equated with threat, political opposition itself became suspect. Measures adopted to prevent stasis risked reproducing it in another form, concentrating power rather than reconciling divisions.

The tension between order and freedom thus occupied the center of Greek political reflection. Stability was necessary, but the means of securing it mattered profoundly. Greek thinkers did not deny the reality of internal danger. They questioned the cure. When order was imposed by force loyal to an individual rather than to the community, the city avoided immediate collapse only to surrender its autonomy. The fear of stasis, when exploited rather than contained, became the most reliable path to tyranny.

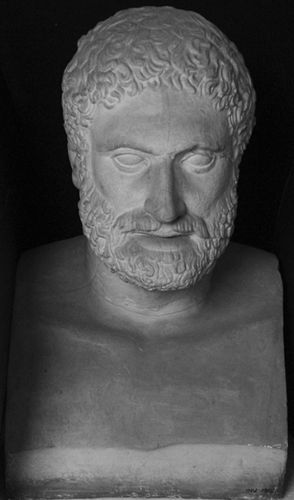

Peisistratos and the Logic of the Bodyguard

Peisistratos’ rise to power in sixth-century Athens offers a canonical illustration of how tyranny could emerge through legal and civic mechanisms rather than open force. According to ancient accounts, Peisistratos presented himself as a victim of political enemies, displaying self-inflicted wounds to dramatize the danger he faced. On this basis, he requested permission from the Athenian assembly to maintain a small personal guard for protection. The request was framed not as an assertion of dominance, but as a defensive necessity grounded in public concern for order and safety.

Crucially, the assembly consented. The bodyguard granted to Peisistratos was modest in size and explicitly authorized, reflecting the belief that limited force could be safely contained. This moment reveals the vulnerability embedded in civic trust. The Athenians did not imagine themselves surrendering self-rule. They believed they were temporarily reinforcing it. Yet the guard’s loyalty was not to the polis, but to Peisistratos himself. That distinction, seemingly minor at the outset, proved decisive.

Once established, the bodyguard became the instrument through which Peisistratos repeatedly seized control of the city. His power did not rest on abolishing laws or dissolving institutions. Assemblies continued, magistracies remained, and legal forms persisted. What changed was the balance of coercive power underlying those forms. The presence of an armed force personally loyal to Peisistratos allowed him to intimidate rivals, suppress resistance, and re-enter power even after periods of exile.

Greek writers treated this episode as a political warning rather than a historical curiosity. The danger lay not in the size of the guard, but in its allegiance. Peisistratos’ tyranny began the moment force was detached from civic accountability and attached to an individual’s survival. The lesson was stark: once a city authorizes personal security in the name of public order, it risks creating the very domination it seeks to prevent.

From Protection to Control: When Force Changes Its Allegiance

The decisive transformation in the rise of tyranny occurs not when force is introduced, but when its allegiance shifts. Greek cities were familiar with arms in civic life. Citizen militias, hoplite levies, and temporary commands were accepted features of collective defense. What distinguished tyrannical force was not its existence, but its orientation. Protection became control when armed power answered to a person rather than to the community.

This shift often unfolded gradually. A bodyguard authorized for protection could plausibly be presented as limited, temporary, and necessary. Yet once established, such forces altered the political landscape by their mere presence. They introduced an asymmetry into civic life. Political opponents were no longer confronting arguments or votes alone, but the implicit threat of coercion. Even without overt violence, the knowledge of personal loyalty to a ruler reshaped behavior.

Greek observers recognized that this change undermined freedom without abolishing law. Tyrants rarely dismantled institutions outright. Assemblies met, magistrates served, and courts functioned. What changed was the context in which decisions were made. Deliberation under the shadow of personal force is deliberation in form only. Consent extracted in such conditions is indistinguishable from submission.

The redirection of force also narrowed political possibility. Once coercion became personal, compromise lost meaning. Rivals faced not policy defeat but physical vulnerability. Opposition hardened or disappeared, not because it was intellectually overcome, but because it became dangerous. Political life contracted around the will of the individual who controlled protection, and the city’s capacity for self-correction evaporated.

Greek political theory treated this moment as the point of no return. A city could survive disorder and recover. It could endure faction and reconcile. What it could not survive was the personalization of force. When protection ceased to be a civic function and became an instrument of personal rule, the polis retained its appearance but lost its substance. Tyranny, in Greek understanding, began not with violence, but with misplaced trust in who held the weapons.

Greek Political Theory and the Fear of Standing Armies

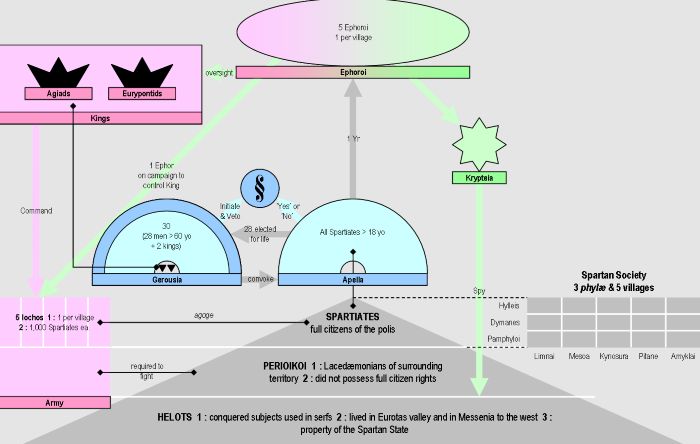

Greek political thought developed an enduring suspicion of permanent armed forces detached from the citizen body. This suspicion was not rooted in pacifism, but in a clear-eyed assessment of power. Greeks understood that force, once professionalized and continuous, acquired interests of its own. When arms ceased to be an obligation of citizenship and became a specialized function, the balance between ruler and ruled shifted decisively.

In the classical polis, military service was ideally temporary and collective. Citizens armed themselves to defend the community and then returned to private life. This model preserved reciprocity between political obligation and political voice. Standing forces, by contrast, disrupted that equilibrium. Soldiers who depended on pay, protection, or favor from a single leader became politically unaccountable. Their loyalty followed survival rather than law.

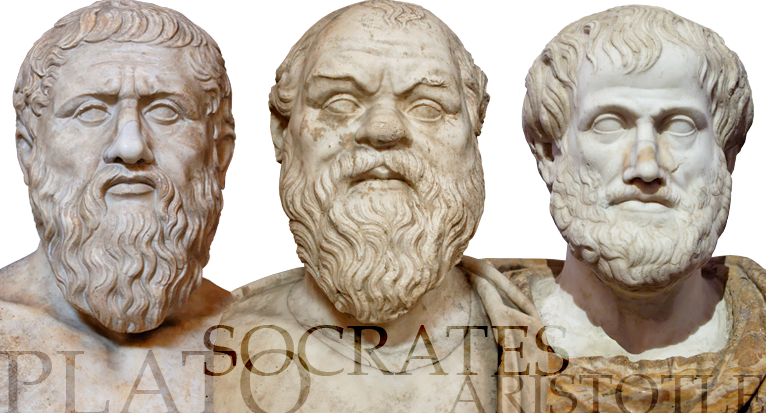

This concern appears repeatedly in Greek philosophical reflection. Plato, despite his openness to hierarchical order, warned that guardians must be carefully constrained lest they become rulers in fact rather than function. His anxiety was not abstract. A class trained exclusively in violence and detached from civic life risked transforming protection into domination. Discipline without accountability, in Plato’s view, was indistinguishable from tyranny.

Aristotle articulated this insight with greater institutional precision. In his analysis of constitutions, he identified control of arms as the defining feature of political power. Democracies survived when citizens collectively bore arms. Oligarchies and tyrannies emerged when weapons were monopolized by a narrow group or an individual. For Aristotle, the question of who possessed force was inseparable from the question of who ruled.

Greek hostility toward mercenaries reinforced this logic. Mercenary soldiers, common in later Greek warfare, embodied the dangers of standing armies. They fought for pay, not for the polis, and could be redeployed against their employers with ease. Greek authors repeatedly associated mercenary reliance with moral decay and political fragility. A city that outsourced its security had already weakened its sovereignty.

The fear of standing armies was thus not a fear of violence, but of permanence. Temporary emergency measures could be tolerated. Permanent coercive structures could not. Once force became continuous and personal, it ceased to be corrective and became constitutive of rule. Greek political theory treated this transition as fatal to self-government.

What emerges from these reflections is a remarkably modern insight. Republican freedom depends less on the absence of force than on its distribution. Arms may exist without tyranny. Tyranny begins when arms answer consistently to one will. Greek thinkers did not imagine that law alone could restrain power. They understood that whoever commands the soldiers ultimately commands the city.

Law without Liberty: Tyranny beneath Legal Forms

Greek observers were acutely aware that tyranny did not require the abolition of law. On the contrary, some of the most durable tyrannies preserved legal institutions precisely to cloak domination in familiarity. Courts continued to operate, magistracies remained occupied, and civic rituals persisted. What changed was not the existence of law, but its function. Law ceased to be an expression of collective self-rule and became an instrument managed under coercive conditions.

This distinction mattered deeply to Greek political theory. Freedom, in their understanding, did not consist merely in living under laws, but in participating meaningfully in their formation and enforcement. When force answered to a single ruler, legal outcomes were predetermined by fear even if procedures appeared intact. Decisions rendered under the shadow of personal coercion could not be considered free, regardless of their formal legality.

Tyrants often understood this dynamic intuitively. Rather than dismantling institutions that symbolized continuity, they used them to normalize control. By allowing assemblies to meet and laws to be enforced selectively, tyrants avoided provoking open resistance. Citizens could tell themselves that the polis still functioned. The erosion of liberty occurred incrementally, disguised as stability.

Greek writers repeatedly emphasized that this condition was more dangerous than overt lawlessness. Open chaos invited resistance and reform. Legalized domination, by contrast, dulled political awareness. When injustice was routinized through procedure, it became harder to identify and oppose. Tyranny beneath law produced obedience without conviction and order without consent.

This insight explains why Greek political thought treated legality as insufficient for freedom. A city could be lawful and unfree at the same time. Liberty depended on whether citizens could act without fear and whether institutions operated independently of personal force. Once those conditions failed, the preservation of law offered no safeguard. Tyranny did not announce itself by destroying the legal order. It hollowed it out from within.

Security Rhetoric as a Repeating Political Pattern

Greek political thinkers did not treat the rise of tyranny as a unique historical accident. They understood it as a repeatable sequence driven by fear, uncertainty, and the strategic use of security language. The pattern begins with the identification of internal threat. Disorder is emphasized, dissent is magnified, and disagreement is reframed as danger. What follows is a call for exceptional measures, presented as temporary and necessary to preserve the community.

The second stage is authorization. Civic bodies are asked to permit extraordinary force in the name of protection. This step is crucial, because it converts fear into consent. Force is no longer imposed; it is granted. Greek accounts repeatedly stress that tyrants did not seize power in defiance of the polis. They were invited to safeguard it. Legitimacy is thus transferred before domination becomes visible.

Normalization follows. Emergency measures persist beyond their stated purpose, justified by the claim that danger remains. The definition of threat expands, and the exceptional becomes routine. At this point, political opposition itself is recast as a security risk. Dissent is no longer debated but managed. Force, initially justified as defensive, becomes the means by which authority is maintained.

Greek thinkers recognized that this logic does not require overt brutality. Its effectiveness lies in plausibility. Each step appears reasonable when isolated. The danger is cumulative. By the time personal control of force is established, the political community has already accepted the premises that make resistance appear irresponsible. Tyranny arrives not as a rupture, but as continuity under altered conditions.

Later political theorists would formalize this insight. Hannah Arendt identified the way revolutionary and counterrevolutionary regimes alike exploit fear to justify extraordinary authority, while modern scholars traced how states of exception migrate from temporary response to permanent structure. Greek political theory stands at the beginning of this tradition. Its warning is not about armies alone, but about rhetoric. When security becomes the primary political argument, liberty is already negotiating from a position of weakness.

Ancient Warning, Modern Resonance

Greek political thought offers a structural warning rather than a historical analogy. Its insight does not depend on the specifics of hoplites, tyrants, or city-states, but on the logic by which security claims transform political authority. When leaders redefine dissent as threat and present exceptional force as protection, the ancient sequence reappears. The lesson is not that modern polities repeat Greek outcomes mechanically, but that they encounter the same vulnerabilities when fear becomes the primary organizing principle of politics.

What makes this warning durable is its focus on allegiance rather than scale. Greek theorists were less concerned with the size of an armed force than with its answerability. A small guard loyal to one will was more dangerous than a large militia accountable to the community. Modern states possess far greater coercive capacity, but the principle remains unchanged. The danger arises when instruments of force or emergency authority are detached from civilian oversight and attached to personal command.

This logic clarifies why the erosion of norms often precedes the erosion of law. Legal frameworks can survive significant distortion if coercive power enforces compliance. Greek writers recognized that liberty disappears long before statutes are repealed. Modern politics exhibits the same pattern when emergency rhetoric normalizes exceptional measures and recasts opposition as illegitimate. The shift occurs incrementally, often justified as prudence rather than ambition.

The contemporary resonance lies not in imitation, but in recognition. When figures such as Donald Trump label political opponents as existential threats and invoke emergency authority to bypass civilian constraints, they draw from a logic the Greeks already identified as tyrannical in effect, regardless of intent. The ancient warning is not predictive. It is diagnostic. When security becomes personal and force answers to one will, republican government has already begun to recede, even if its legal forms remain intact.

Conclusion: When Force Answers to One

Greek political theory converged on a stark conclusion: republican government ends not when laws disappear, but when force ceases to belong to the community. The decisive transformation is structural rather than theatrical. Once protection becomes personal, freedom becomes conditional. Citizens may continue to deliberate, courts may still convene, and statutes may remain unchanged, yet the substance of self-rule has already been compromised. What matters is not the form of governance, but the chain of command behind coercion.

The Athenian experience with Peisistratos illustrates how easily this transition can be mistaken for prudence. The city did not authorize tyranny. It authorized protection. The error lay in believing that exceptional force could be safely detached from civic accountability without altering political equilibrium. Greek thinkers insisted that this belief was false. Force is never neutral. Whoever commands it shapes the horizon of political possibility, regardless of legal continuity.

This insight explains why Greek authors treated security rhetoric with suspicion even when disorder was real. They did not deny the dangers of internal conflict. They denied that concentrating coercive power in one will could resolve those dangers without creating a greater one. The promise of safety offered by personal force always concealed a transfer of sovereignty. The city might gain temporary calm, but it paid for it with autonomy.

The enduring lesson is therefore neither nostalgic nor alarmist. It is analytical. Republican freedom depends less on declared values than on institutional alignment between law, force, and accountability. When protection answers to the community, law restrains power. When protection answers to one, law becomes decoration. Greek political theory identified this threshold with remarkable clarity. When force answers to one, the republic has already ended, even if it does not yet know it.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

- Aristotle. The Athenian Constitution. Translated by P. J. Rhodes. London: Penguin, 1984.

- —-. Politics. Translated by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998.

- Carugati, Federica. “Building Legal Order in Ancient Athens.” Journal of Legal Analysis 7:2 (2015): 291-324.

- Finley, M. I. Politics in the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. London: Penguin, 2003.

- Mitchell, Lynette G. “Friends and Enemies in Athenian Politics.” Greece & Rome 43:1 (1996): 11-30.

- Ober, Josiah. Democracy and Knowledge. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- —-. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- —-. The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Plato. Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Runciman, David. How Democracy Ends. New York: Basic Books, 2018.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Thomas Hobbes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Węcowski, Marek. “Stasis: Conflict, Revolution, and Compromise in the Greek Polis.” Antigone, March 2, 2024.

- White, Mark. “Greek Tyranny.” Phoenix 9:1 (1955): 1-18.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.21.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.