At every critical juncture, the republic chose order over participation, security over deliberation, and administrative efficiency over democratic legitimacy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Order without Liberty

The collapse of the German Empire in 1918 did not leave behind a vacuum of authority but a state haunted by the fear of disorder. The Weimar Republic emerged amid military defeat, economic collapse, and revolutionary unrest, conditions that produced an overwhelming anxiety about instability. From its inception, the republic defined its primary task not as the expansion of democratic participation but as the restoration of order. This priority shaped the republic’s institutions, its constitutional logic, and its understanding of political legitimacy. Law was not abandoned. It was elevated as the principal instrument through which force could be justified, organized, and deployed.

Weimar’s tragedy does not lie in the absence of legal structure but in its excess. The republic was saturated with law, decrees, regulations, and emergency provisions designed to preserve public order. These mechanisms were framed as temporary responses to extraordinary conditions, yet they quickly became routine tools of governance. Emergency powers were not imposed from outside the constitutional system but activated from within it. The republic did not suspend legality in moments of crisis. It reinterpreted legality so that repression could be administered as lawful necessity.

This transformation altered the relationship between the state and its citizens. Political conflict, which democracy presupposes, increasingly appeared in official discourse as a security threat. Protestors were no longer treated as participants in a contested political order but as dangers to public stability. Policing absorbed military logics, and emergency language displaced constitutional restraint. In this environment, the boundary between civil governance and internal warfare eroded. The state did not imagine itself as arbitrating among competing visions of the republic. It imagined itself as defending order against internal enemies.

The Weimar Republic therefore offers a warning that authoritarianism need not arrive through lawlessness or abrupt constitutional rupture. It can emerge through scrupulous adherence to legal form while emptying democratic substance. When law ceases to function as a restraint on power and becomes instead a technique for its expansion, constitutional government decays from within. The history of Weimar is not a story of democracy overwhelmed by chaos but of democracy disciplined into submission by its own institutions. Order survived. Liberty did not.

The Birth of a Fragile Republic: Fear, Violence, and Legitimacy

The Weimar Republic was born not in triumph but in collapse, and its earliest political instincts were shaped by fear rather than confidence. Germany’s defeat in the First World War produced a disoriented society marked by economic deprivation, mass demobilization, and the psychological shock of imperial disintegration. Millions of soldiers returned home trained for violence, alienated from civilian life, and suspicious of the new political order that had replaced the Kaiser. The republic inherited not only a shattered economy but a population saturated with militarized experience and political bitterness. From the outset, the state confronted unrest not as a temporary adjustment problem but as an existential threat.

Revolutionary upheaval in 1918 and 1919 intensified these anxieties. Workers’ councils, socialist uprisings, and attempted seizures of power convinced many political elites that parliamentary democracy rested on unstable ground. The suppression of the Spartacist uprising in Berlin, carried out with the assistance of right-wing paramilitary forces, set an enduring pattern. The republic survived its first crisis by relying on violence it could not fully control and actors who did not share its democratic commitments. Order was restored, but legitimacy was compromised. The state’s earliest act of self-preservation established a precedent: coercion would be tolerated, even welcomed, when exercised in defense of stability.

This reliance on force was reinforced by the unresolved question of political loyalty. Large segments of the conservative establishment, including the judiciary, police leadership, and civil service, viewed the republic as a provisional arrangement rather than a legitimate regime. Democratic authority lacked deep institutional roots, while imperial habits of command remained intact. The state’s coercive organs were therefore shaped less by republican ideals than by continuity with prewar structures. Violence was not an aberration imposed by extremists alone; it was embedded in the inherited machinery of governance. The republic governed a society that did not yet believe in it.

As a result, Weimar’s leaders increasingly interpreted political dissent through the lens of security rather than representation. Protest, strikes, and radical organizing were framed as symptoms of disorder requiring containment rather than negotiation. The republic’s legitimacy deficit encouraged a defensive posture in which authority was asserted through control rather than consent. This posture did not arise from authoritarian ambition but from institutional insecurity. The tragedy of Weimar lies in the fact that its earliest efforts to protect democracy relied on methods that steadily undermined it. Fear shaped governance, violence stabilized the moment, and legitimacy quietly eroded beneath the surface.

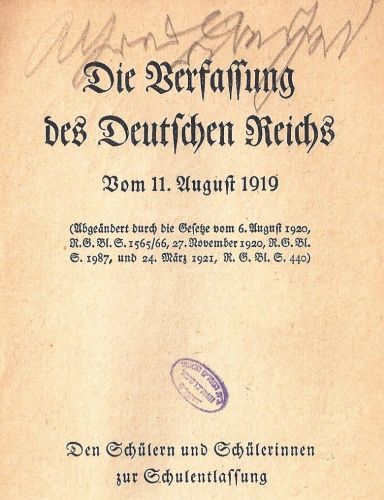

Article 48 and the Architecture of Emergency Power

At the center of Weimar’s constitutional structure stood Article 48, a provision intended to safeguard the republic in moments of grave danger. Drafted in the aftermath of imperial collapse and revolutionary upheaval, the article granted the president authority to suspend civil liberties and rule by decree when public order was seriously disturbed or endangered. In theory, these powers were defensive and temporary, designed to protect parliamentary democracy from forces seeking its destruction. In practice, Article 48 embedded a logic of exception into the heart of the constitutional system. Emergency authority was not external to democratic governance but constitutionally authorized as one of its mechanisms.

The early use of Article 48 reinforced the perception that emergency rule was both legitimate and necessary. Initial decrees responded to real crises, including political violence, economic instability, and regional unrest. Each invocation was justified as an extraordinary measure suited to extraordinary conditions. Yet repetition transformed exception into habit. As emergency decrees multiplied, the distinction between normal governance and crisis response blurred. Parliamentary deliberation increasingly appeared slow and inadequate compared to the efficiency of executive action. Law itself adapted to crisis, redefining stability as the highest constitutional value.

This shift altered the balance of power within the republic. Article 48 gradually detached authority from legislative accountability and relocated it in the executive branch. Although the Reichstag formally retained the right to revoke emergency decrees, political fragmentation and persistent instability weakened this safeguard. The constitutional system thus permitted the systematic bypassing of representative institutions without violating formal legality. Governance by decree did not require a coup. It required only the sustained perception that democracy was perpetually under threat.

The architecture of emergency power created by Article 48 therefore functioned less as a shield than as a framework for authoritarian drift. By normalizing suspension in the name of preservation, the republic habituated itself to governing without consent. Emergency powers became tools not merely for survival but for administration. The state learned to rule through urgency, and legality learned to accommodate repression. Weimar’s constitution did not collapse under pressure. It bent, repeatedly and lawfully, until democratic restraint no longer defined the limits of power.

From Civil Policing to Internal Security Forces

The evolution of policing in the Weimar Republic reveals how a nominally civilian institution absorbed military assumptions without formal transformation. German policing after 1918 retained deep structural continuity with imperial models that emphasized discipline, hierarchy, and coercive authority. Police forces were trained not primarily as mediators of civil life but as instruments of order maintenance. This orientation was intensified by the perception that the republic faced constant internal threat. Policing did not adapt to democratic pluralism so much as democracy adapted itself to inherited security practices.

Material and tactical changes accelerated this transformation. Police units were increasingly equipped with military-grade weapons, armored vehicles, and crowd-control technologies developed for battlefield conditions. Training emphasized rapid deployment, force concentration, and suppression rather than negotiation or restraint. The language of policing shifted accordingly. Civil unrest was framed as internal warfare, and demonstrators were treated less as citizens exercising political rights than as hostile forces destabilizing the state. The distinction between policing crime and confronting enemies blurred until it lost operational meaning.

This militarization was reinforced by institutional psychology. Police officers often viewed themselves as guardians of order standing between civilization and chaos. Democratic politics, with its strikes, protests, and ideological conflict, appeared to many within the security apparatus as inherently destabilizing. The republic’s reliance on police to resolve political conflict further entrenched this mindset. Each deployment against civilians normalized the use of force as a governing tool. The police became not simply enforcers of law but arbiters of political acceptability.

The consequences were profound. As policing adopted the logic of internal security, constitutional protections weakened in practice even when they remained formally intact. Assembly, expression, and association survived on paper but were contingent on the state’s security assessment. This transformation did not require explicit authoritarian intent. It emerged through routine administrative decisions made under pressure. By the early 1930s, Weimar’s police functioned less as servants of a democratic society than as a standing internal security force prepared to treat portions of the population as adversaries. The republic did not militarize overnight. It disciplined itself into coercion.

Paramilitaries, Auxiliary Forces, and State Delegation of Violence

The Weimar Republic’s security crisis was not addressed solely through formal state institutions. Alongside the police and military stood a dense ecosystem of paramilitary organizations that operated in the shadow space between legality and illegality. These groups, composed largely of demobilized soldiers and radicalized civilians, emerged from the violent dislocations of defeat and revolution. Rather than dismantling them decisively, the republic often tolerated, regulated, or quietly relied upon their existence. The state did not monopolize violence so much as manage it through selective partnership.

The Freikorps represented the most prominent expression of this phenomenon. Originally mobilized to suppress left-wing uprisings in the immediate postwar period, these formations combined extreme nationalist ideology with military discipline and a deep hostility toward democratic governance. Their deployment against socialist and communist movements was justified as an emergency necessity. Although formally disbanded after their most visible campaigns, the networks, personnel, and ethos of the Freikorps persisted. Many members transitioned seamlessly into other paramilitary organizations or entered the police and security services, carrying their assumptions with them.

This pattern revealed a deeper structural failure. The republic delegated violence to actors who did not accept its legitimacy, calculating that their utility outweighed the risks. Right-wing paramilitaries were often treated as stabilizing forces, while left-wing groups were criminalized as existential threats. Enforcement was uneven, prosecutions selective, and punishments asymmetrical. Violence committed in defense of order was minimized or excused, while violence associated with revolutionary politics was pursued aggressively. Law did not disappear in this process. It became a filter through which certain forms of violence were normalized.

Auxiliary police formations further blurred the boundary between state authority and partisan force. During periods of unrest, governments authorized temporary security units drawn from nationalist organizations, granting them policing powers under legal cover. These auxiliaries expanded the coercive capacity of the state while insulating it from direct accountability. Because their authority was framed as provisional, their actions were treated as anomalies rather than precedents. Yet repetition converted exception into practice. Temporary forces reappeared whenever stability was questioned, reinforcing the logic that legality could be extended to irregular violence.

The judicial system reinforced this delegation through permissive interpretation. Courts frequently treated paramilitary violence as politically understandable, even when technically unlawful. Sentencing patterns favored right-wing offenders and minimized the political significance of their actions. This judicial indulgence communicated a clear message: violence aligned with state interests would encounter limited resistance. The republic thus cultivated a coercive environment in which legality functioned less as a constraint than as a signaling mechanism, indicating which actors could operate with impunity.

By the early 1930s, this system of delegated violence had hollowed out the republic’s moral authority. The state no longer stood as an impartial guarantor of order but as a coordinator of coercive forces whose loyalty to democracy was conditional at best. Paramilitaries did not undermine the republic from the outside alone. They were incorporated into its security logic. When authoritarian power later consolidated itself, it inherited not chaos but a ready-made infrastructure of sanctioned violence. The republic did not lose control of force. It shared it, selectively and fatally.

Courts, Decrees, and the Judicial Normalization of Repression

The judiciary of the Weimar Republic occupied a paradoxical position within the constitutional order. Charged with upholding the rule of law, courts nonetheless became key agents in the normalization of repression. This was not the result of overt judicial subservience to authoritarian power but of institutional continuity and ideological predisposition. Many judges had been trained under the imperial system and retained deep skepticism toward republican democracy. Their understanding of law emphasized order, authority, and state continuity rather than popular sovereignty. As a result, judicial interpretation often aligned instinctively with executive efforts to contain political unrest.

Emergency decrees issued under Article 48 provided the legal framework through which this alignment became operational. Courts routinely accepted the president’s assessment that extraordinary conditions justified extraordinary measures. Rather than scrutinizing the necessity or proportionality of these decrees, judges treated them as legitimate expressions of constitutional authority. This deference effectively insulated executive action from meaningful judicial review. Legal challenge became procedural rather than substantive, focused on formal validity rather than democratic impact. In this way, repression acquired the appearance of routine administration.

Political trials further illustrate the judiciary’s role in shaping unequal legal outcomes. Defendants associated with left-wing movements were frequently prosecuted aggressively and punished harshly, while right-wing offenders often received lenient sentences or sympathetic treatment. Judges framed this disparity not as political bias but as protection of public order. Violence committed in defense of the state was interpreted as excess rather than threat, while violence against the state was treated as criminal subversion. Equal protection existed as doctrine but not as practice. Law functioned as a sorting mechanism that distinguished acceptable from unacceptable politics.

This judicial posture reinforced a broader cultural shift in the meaning of legality. Courts did not merely apply emergency powers; they normalized them by embedding repression within ordinary legal procedure. Preventive detention, bans on assembly, and restrictions on expression were processed through courts as technical matters rather than constitutional crises. Each ruling narrowed the practical space of democratic life while preserving the formal language of legality. The judiciary thus contributed to a legal environment in which repression was rendered mundane and contestation increasingly futile.

By the early 1930s, the cumulative effect of judicial normalization was unmistakable. Law no longer served primarily as a boundary limiting state power but as a mechanism facilitating its expansion. Courts had not abandoned legality. They had redefined it. When authoritarian rule later consolidated itself, it encountered a judiciary already accustomed to subordinating rights to order and procedure to necessity. The transition did not require the destruction of the legal system. It required only its continuation.

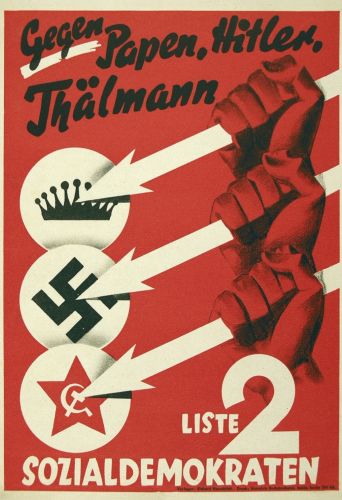

Policing Political Identity: Communists, Social Democrats, and the “Enemy Within”

As the Weimar Republic struggled to stabilize itself, political opposition increasingly ceased to be understood as a feature of democratic life and was instead reframed as a security problem. This shift did not occur uniformly across the political spectrum. From the early 1920s onward, state surveillance, policing, and emergency measures disproportionately targeted left-wing movements, particularly communists and, at times, social democrats. Political identity itself became a marker of suspicion. The republic’s coercive apparatus learned to classify citizens not by actions alone but by ideological affiliation.

Communist organizations were the primary targets of this security logic. The Communist Party of Germany was treated not merely as a political rival but as an existential threat to the state. Police surveillance, bans on assembly, and arrests under emergency decrees were justified as preventive measures designed to forestall revolution. Even when communist activity remained within legal bounds, it was framed as inherently destabilizing. Law enforcement thus shifted from responding to criminal acts to managing perceived political danger. Dissent became actionable before it manifested as violence.

Social Democrats, despite their role as architects and defenders of the republic, were not immune to this logic. During periods of unrest, socialist-led unions, strikes, and demonstrations were often suppressed under the same emergency provisions used against more radical movements. The distinction between reformist and revolutionary politics blurred in the eyes of security authorities. When stability was threatened, democratic credentials offered limited protection. The state’s reliance on emergency powers gradually transformed political pluralism into a liability rather than a strength.

This policing of political identity extended beyond overt repression into administrative control. Surveillance files, intelligence gathering, and preventive restrictions created a climate in which political participation carried personal risk. Individuals known for left-wing affiliations could face employment consequences, travel restrictions, or detention without trial. These measures were rarely framed as punitive. They were described as precautionary, necessary to preserve order. Yet their cumulative effect was to narrow the boundaries of acceptable political life.

The asymmetry of enforcement was critical. Right-wing movements, even when openly hostile to the republic, were often treated as misguided patriots rather than enemies. Left-wing politics, by contrast, was coded as foreign, subversive, and corrosive. This imbalance reinforced a security narrative in which the republic defined itself against one segment of its own population. The “enemy within” was not an abstract category. It was socially and politically specific, and it shaped how law was applied.

By institutionalizing suspicion toward political identity, the Weimar state undermined its own democratic foundation. Citizenship ceased to guarantee equal standing before the law. Instead, legitimacy became conditional, contingent on perceived loyalty to an order defined by security rather than participation. This transformation did not require the abolition of parties or elections. It required only the steady application of legal mechanisms that treated dissent as danger. In policing political identity, the republic disciplined democracy itself, preparing the conceptual ground for authoritarian rule.

Emergency as Permanence: Governing without Parliament

By the late 1920s, the Weimar Republic had entered a phase in which emergency governance was no longer episodic but structural. What had once been justified as a response to acute instability hardened into a routine method of rule. Parliamentary coalitions fractured under economic pressure, electoral volatility, and ideological polarization, rendering legislative consensus increasingly elusive. Rather than restore parliamentary authority, the state compensated for its weakness by leaning more heavily on executive decree. Emergency powers ceased to function as a bridge back to normal politics and instead became a substitute for it.

This transformation accelerated dramatically during the economic crises of the early 1930s. As mass unemployment, deflation, and social desperation intensified, governments increasingly bypassed the Reichstag altogether. Presidential cabinets ruled through Article 48 decrees, framing parliamentary debate as a luxury the nation could no longer afford. Each decree was formally legal, constitutionally grounded, and publicly defended as unavoidable. Yet the cumulative effect was to hollow out representative government while preserving its outward form. Parliament existed, but it no longer governed.

The normalization of decree-rule reshaped political expectations. Citizens and officials alike adjusted to a system in which democratic deliberation was marginal and executive action decisive. Crisis rhetoric became self-sustaining. Because emergency governance foreclosed democratic solutions, instability persisted, which in turn justified further emergency measures. The republic entered a feedback loop in which legality reinforced authoritarian habits. Law did not restrain power; it rationalized its concentration. What appeared as paralysis was in fact transformation.

By the time the republic reached its final years, the constitutional balance had already collapsed in practice. Governing without parliament no longer seemed exceptional or alarming. It seemed efficient. This habituation proved fatal. When authoritarian leadership finally asserted itself openly, it encountered a political culture already accustomed to rule by decree and emergency logic. The republic did not surrender its powers in a single moment of crisis. It dissolved them gradually, through lawful mechanisms that replaced democratic governance with administrative command.

From Weimar to the Third Reich: Continuity Rather than Break

The transition from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich is often narrated as a dramatic rupture, a sudden collapse of democracy followed by the imposition of dictatorship. This interpretation obscures a more unsettling reality. Much of the coercive, legal, and administrative machinery that sustained Nazi rule was not invented after 1933 but inherited. The Nazi seizure of power did not require the destruction of the Weimar state because the state had already been reconfigured to prioritize order, security, and executive authority over democratic restraint. What changed was not the architecture of power but its ideological direction.

Police institutions exemplify this continuity. By 1933, German policing had already adopted militarized tactics, internal security assumptions, and expansive discretionary authority. Emergency powers had normalized aggressive intervention against perceived enemies of the state. Surveillance practices, preventive detention, and bans on political activity were familiar tools. The Nazi regime did not need to invent new methods of repression. It needed only to redirect existing ones toward new targets. The police did not undergo immediate structural overhaul. They continued operating within a framework already accustomed to treating civilians as threats.

Legal continuity was equally significant. Courts that had legitimized emergency decrees under Weimar continued to function after the Nazi takeover with minimal institutional resistance. Judges trained to defer to executive authority and prioritize state security adapted quickly to the new regime’s demands. The concept of legality had already been stretched to accommodate repression. Under National Socialism, it was stretched further, but along a familiar trajectory. The legal profession did not confront a foreign system imposed from outside. It encountered an intensification of principles it had already internalized.

Administrative governance followed a similar pattern. Rule by decree, marginalization of parliament, and concentration of power in the executive were not Nazi innovations. They were established practices by the early 1930s. When Adolf Hitler assumed the chancellorship, the machinery for governing without legislative consent was already in place. The Reichstag Fire Decree and subsequent measures radicalized emergency authority, but they relied on constitutional habits forged during the republic’s final years. Authoritarian consolidation proceeded with alarming speed because the institutional groundwork had been laid.

This continuity challenges the comforting notion that democratic collapse announces itself clearly. The Weimar Republic did not fall because it lacked law or institutions. It fell because those institutions were repurposed to suppress the very political life they were meant to sustain. By the time the Nazis entered government, democratic norms had been hollowed out through years of emergency governance. The republic had already taught itself to function without liberty. Dictatorship did not emerge from chaos. It emerged from order.

Understanding this continuity does not absolve National Socialism of responsibility for its crimes. It clarifies how those crimes became administratively possible. The Third Reich did not appear ex nihilo. It inherited a state disciplined by fear, habituated to repression, and confident in the legality of coercion. The lesson of Weimar is therefore not that democracy is fragile because it lacks strength, but that it is vulnerable when strength is pursued without restraint. The road to dictatorship was paved not with lawlessness, but with law meticulously applied.

Transhistorical Warning: Security Language and Democratic Decay

The history of the Weimar Republic demonstrates that democratic decay rarely announces itself through the open rejection of law. More often, it proceeds through the steady expansion of security language that reframes political conflict as existential threat. In Weimar, emergency powers, militarized policing, and preventive repression were justified as rational responses to instability. Each measure was defended as temporary, proportionate, and necessary. Together, they produced a governing logic in which order eclipsed liberty and legality masked coercion. The danger lay not in the abandonment of constitutionalism but in its redefinition.

Security language possesses a particular power within democratic systems because it claims moral urgency. By framing dissent as danger and opposition as disorder, it narrows the space for political disagreement without formally eliminating it. Democratic procedures remain intact in appearance, yet their substance is altered. Debate becomes suspect, delay becomes irresponsible, and restraint becomes weakness. In such an environment, the expansion of coercive authority appears not as an erosion of democracy but as its defense. Weimar illustrates how easily this logic becomes self-reinforcing.

The transhistorical relevance of this pattern lies in its subtlety. Authoritarianism need not arrive through dramatic constitutional rupture or revolutionary seizure of power. It can advance incrementally through legal measures that enjoy broad support in moments of fear. Militarized policing, emergency governance, and expansive surveillance are often introduced as responses to immediate crises. Over time, they reshape political culture, normalize exceptional authority, and redefine citizenship in security terms. The result is not sudden tyranny but administrative domination.

Weimar’s warning is not confined to a particular historical moment or ideological context. It speaks to a structural vulnerability within constitutional democracies themselves. When security becomes the primary lens through which politics is understood, law risks becoming an instrument of command rather than restraint. Democratic decay occurs not when institutions fail, but when they succeed too well at enforcing order without preserving freedom. The lesson is not that states should forgo security, but that they must resist the temptation to let security logic displace constitutional principle.

Conclusion: When Law Stops Protecting and Starts Commanding

The failure of the Weimar Republic was not the result of insufficient authority but of authority exercised without restraint. At every critical juncture, the republic chose order over participation, security over deliberation, and administrative efficiency over democratic legitimacy. These choices were not imposed by anti-democratic forces alone. They were made through lawful procedures, constitutional mechanisms, and institutional routines designed to preserve the state. Law did not collapse under pressure. It adapted, expanding its reach until it no longer functioned as a boundary on power.

Weimar’s experience reveals the danger of treating repression as a stabilizing force rather than a corrosive one. Emergency powers, militarized policing, and judicial deference were repeatedly justified as temporary necessities. Yet each invocation normalized coercion and narrowed the space for political life. Democracy was not overthrown in a single decisive moment. It was disciplined into passivity through legal means that rendered resistance increasingly illegible. By the time authoritarian rule emerged openly, the republic had already learned how to govern without liberty.

The central lesson of Weimar is therefore not about constitutional weakness but constitutional misdirection. A legal system can be robust, coherent, and procedurally meticulous while still facilitating democratic collapse. When law ceases to protect citizens against the state and instead becomes a technique for managing them, constitutionalism loses its moral foundation. Authority may persist, institutions may endure, and order may be maintained. What disappears is the reciprocal relationship between power and consent that defines democratic governance.

Weimar reminds us that the gravest threat to democracy often comes not from those who reject law, but from those who wield it too confidently. A republic does not die only when its rules are broken. It can die when its rules are obeyed in ways that hollow out their purpose. When law stops protecting and starts commanding, democracy survives only in name. The tragedy of Weimar is that this transformation occurred not through chaos, but through order, carefully and legally imposed.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Bessel, Richard. Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism: The Storm Troopers in Eastern Germany, 1925–1934. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich. The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. New York: Praeger, 1970.

- Broué, Pierre. The German Revolution, 1917–1923. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

- Dyzenhaus, David. The Constitution of Law: Legality in a Time of Emergency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- —-. Legality and Legitimacy: Carl Schmitt, Hans Kelsen and Hermann Heller in Weimar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Emsley, Clive. Gendarmes and the State in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Press, 2003.

- Fraenkel, Ernst. The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship. New York: Oxford University Press, 1941.

- Haffner, Sebastian. Failure of a Revolution: Germany 1918–1919. New York: Plunkett Lake Press, 1986.

- Hsi-Huey Liang. The Berlin Police Force in the Weimar Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

- Jones, Mark. Founding Weimar: Violence and the German Revolution of 1918-1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Kolb, Eberhard. The Weimar Republic. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Mann, Michael. The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Mommsen, Hans. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Müller, Ingo. Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Orlow, Dietrich. “1918/19: A German Revolution.” German Studies Review 5:2 (1982): 187-203.

- Scheuerman, William E. Between the Norm and the Exception: The Frankfurt School and the Rule of Law. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

- —-. Liberal Democracy and the Social Acceleration of Time. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Stibbe, Matthew. “From the Wartime State of Siege to Weimar’s Early Years: Parliamentarism and States of Emergency in Germany, 1914–1924.” First World War Studies 14:1 (2023): 91-113.

- Stolleis, Michael. A History of Public Law in Germany, 1914–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Weinhauer, Klaus. “Police and Political Violence in the Weimar Republic.” In Policing Western Europe, edited by Clive Emsley and Barbara Weinberger. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

- Weitz, Eric D. Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Wildt, Michael. An Uncompromising Generation: The Nazi Leadership of the Reich Security Main Office. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.21.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.