The Qing suppression of the Taiping Rebellion reveals a pattern of state survival that carries profound institutional costs.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Rebellion, Delegation, and the Crisis of Qing Authority

The Taiping Rebellion erupted not simply as a military uprising but as a profound challenge to the Qing state’s capacity to govern. Its scale, duration, and ideological reach exposed weaknesses that had long existed beneath the surface of imperial administration. What confronted the Qing court in the 1850s was not only an armed movement controlling vast territories, but the sudden collapse of assumptions about how authority, law, and force were meant to function together. The rebellion forced the state to choose between preserving centralized control in theory and surviving through improvisation in practice.

Before the Taiping crisis, Qing governance rested on a carefully balanced system of bureaucratic hierarchy, formal military command, and legal oversight. Civil administration, taxation, and justice were coordinated through a centralized bureaucracy that depended on documentation, reporting, and chains of accountability. The imperial military, though not without internal problems, was formally integrated into this structure and theoretically subject to civilian oversight. Order depended on the assumption that violence, when used, would be exercised by recognized forces operating under imperial authority and constrained by legal norms. The rebellion shattered this equilibrium. Conventional armies proved inadequate to confront a movement of such size and geographic reach, communications between the capital and the provinces faltered, and imperial directives lost their practical force across large regions. As rebellion spread, the state’s ability to enforce its own legal standards weakened alongside its military position.

In response, the Qing government authorized a radical departure from established practice. Provincial officials were empowered to raise militias, organize irregular armies, and finance enforcement locally, often drawing on gentry networks and regional resources rather than imperial institutions. These forces operated with uneven supervision and only tenuous integration into existing legal frameworks. Paperwork, oversight, and centralized review frequently lagged behind events or disappeared altogether. Delegation replaced command as the primary mode of governance under crisis. Authority fractured as responsibility for security shifted downward to regional actors whose legitimacy rested less on legal authorization than on their capacity to suppress rebellion. This transformation was not a brief suspension of normal order. It reconfigured the relationship between center and periphery and altered the state’s monopoly on coercion in ways that would persist long after the rebellion itself.

What follows argues that the Qing suppression of the Taiping Rebellion illustrates the dangers inherent in delegating force without robust legal restraint. The escalation of civilian violence did not stem solely from ideological fanaticism or battlefield brutality. It emerged from the erosion of centralized authority and the absence of effective oversight over those empowered to enforce order. By examining the Qing state’s turn toward provincial militias and irregular forces, this study shows how internal policing unmoored from law transformed security into localized coercion, with devastating consequences for civilian populations.

The Qing State before the Taiping Rebellion: Central Authority and Legal Order

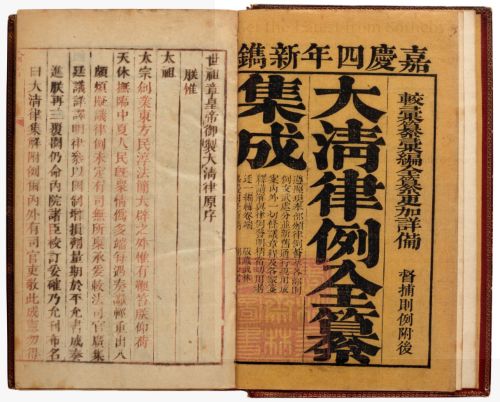

Before the outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion, the Qing dynasty governed through a political system that emphasized centralization, bureaucratic regularity, and legal continuity. Imperial authority rested on a vast civil service staffed through the examination system, which produced officials trained in administrative norms, documentary practice, and moral governance. This bureaucracy functioned through layered hierarchies of reporting, in which county magistrates submitted memorials upward through provincial channels to the central court. Governance depended on paperwork, precedent, and routinized procedure. Law was not conceived primarily as a set of individual protections but as an administrative framework designed to preserve order, manage populations, and maintain imperial stability through predictable processes.

Military power was formally integrated into this bureaucratic structure. The Banner forces and the Green Standard Army were distinct institutions, but both operated within the imperial system rather than outside it. Officers were appointed through official channels, budgets were centrally allocated, and military actions were theoretically subject to civilian oversight. Although corruption and inefficiency were persistent problems, the Qing state maintained a clear conceptual boundary between authorized force and illegitimate violence. The monopoly on coercion belonged to the state, and that monopoly was exercised through recognized institutions rather than ad hoc arrangements.

Legal order reinforced this structure in important ways. Qing law emphasized responsibility and accountability, particularly for officials whose failure to maintain order could result in investigation, demotion, or punishment. Magistrates were personally liable for disturbances within their jurisdictions, creating strong incentives to prevent disorder before it escalated. Judicial procedures relied heavily on written documentation, confession, and multi-level review, embedding coercion within a paper trail that linked local action to imperial authority. While harsh by modern standards and often coercive in practice, this system nonetheless aimed to channel violence through established forms. Force was meant to appear as the execution of law rather than its suspension, preserving the legitimacy of the state even when punishment was severe.

Central authority was therefore not merely symbolic. It depended on the assumption that imperial directives could be transmitted, interpreted, and enforced across the empire with reasonable consistency. This assumption underwrote both taxation and security. Even in times of unrest, the expectation remained that force would be deployed by agents clearly identifiable as representatives of the state, operating within known legal boundaries. Stability depended on the credibility of this expectation.

The significance of this pre-rebellion order lies in what followed. The Qing response to the Taiping crisis did not emerge from an absence of legal or administrative tradition, nor from an inherently weak state. It emerged from the strain placed on a system that depended on centralized authority, documentary accountability, and procedural restraint. When that system proved incapable of containing rebellion on such a scale, the solution adopted was not reform but delegation. Understanding the coherence of Qing governance before the Taiping Rebellion is therefore essential for grasping the magnitude of the rupture that followed, as the state abandoned many of its own legal assumptions to survive. What emerged was not continuity under pressure, but a transformation in how authority and force were exercised within the Qing dynasty.

The Taiping Rebellion as an Existential Challenge to the State

The Taiping Rebellion confronted the Qing state with a crisis unlike any it had previously faced. What began as a heterodox religious movement rapidly evolved into a mass insurgency that seized territory, mobilized populations, and established a rival political order. By the early 1850s, the rebellion controlled large portions of southern China and threatened key economic and administrative centers. Its durability and scale transformed it from a regional disturbance into an existential challenge to imperial survival.

One dimension of this threat lay in the rebellion’s ideological ambition, which struck at the moral foundations of Qing rule. The Taiping leadership did not seek accommodation within the existing imperial framework or recognition as a regional power. It rejected Qing authority outright, denounced Confucian orthodoxy, and advanced a radical theological vision that claimed divine legitimacy independent of the imperial order. This ideological posture undermined the symbolic authority on which the dynasty relied, particularly its claim to rule through moral cultivation and cosmic harmony. Traditional strategies of suppression, such as negotiation with elites or selective coercion, proved ineffective against a movement that defined compromise as apostasy. The rebellion’s ideology thus transformed military conflict into a contest over legitimacy itself.

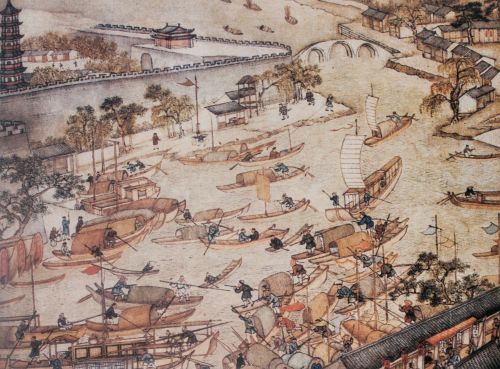

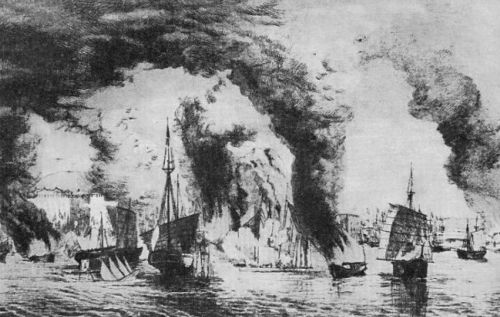

The geographic spread of the conflict compounded the danger. Taiping forces operated across vast territories, disrupting tax collection, grain transport, and communications between the capital and the provinces. River systems that had long served as arteries of imperial control became contested spaces. County administrations collapsed or fled, leaving large civilian populations without effective governance. In many regions, imperial authority existed only in name, eroding the credibility of the state’s claim to rule.

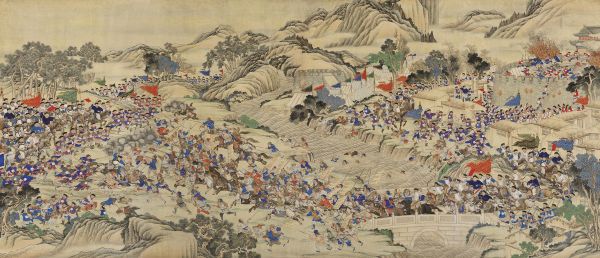

Conventional Qing military forces proved unequal to this challenge. Banner armies were overstretched, poorly supplied, and increasingly ineffective against highly motivated rebel forces. The Green Standard Army, designed for routine policing rather than sustained civil war, struggled with desertion and logistical breakdown. Repeated failures not only weakened military capacity but also damaged the legitimacy of the imperial response. Each defeat reinforced the perception that the state could no longer enforce its will through established institutions.

The rebellion also exposed structural weaknesses within the imperial system itself, particularly the limitations of bureaucratic governance under conditions of rapid crisis. Decision-making slowed as memorials lagged behind events unfolding at unprecedented speed. Orders issued from the capital often arrived too late to matter or proved impossible to implement in regions already destabilized. Officials were forced into discretionary action, balancing survival against adherence to legal norms. This erosion of procedural governance was not merely a practical inconvenience. It represented a fundamental breakdown in the mechanisms that linked imperial authority to local enforcement, leaving the state increasingly reactive rather than directive.

By the mid-1850s, it was clear that the Taiping Rebellion threatened not merely territorial integrity but the foundational assumptions of Qing rule. The state’s monopoly on legitimate violence fractured as authority slipped from centralized command into improvised local responses. Faced with the prospect of collapse, the court sanctioned extraordinary delegation, empowering provincial actors to act independently in the name of survival. In the Qing dynasty, this moment marked a decisive shift. The rebellion functioned not only as a military emergency but as a catalyst for transforming how power, law, and coercion were exercised, setting the stage for a new and more dangerous form of internal policing.

Delegated Force: Provincial Militias and Irregular Armies

Confronted with the inadequacy of conventional forces, the Qing court turned to delegation as a strategy of survival. Provincial officials were authorized to raise militias, recruit soldiers outside the formal Banner and Green Standard systems, and finance military operations through local means. This shift marked a decisive break from earlier assumptions about centralized command and legal oversight.

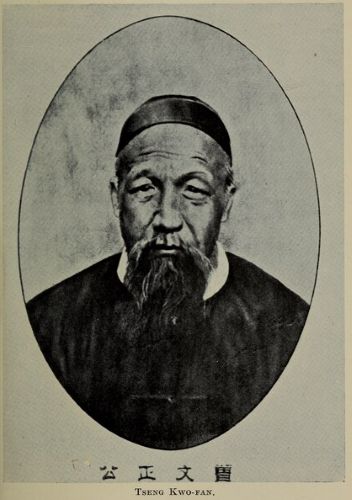

The most prominent of these forces were the provincial armies organized by scholar-officials such as Zeng Guofan. Drawing on local gentry networks, kinship ties, and regional loyalties, these armies were effective precisely because they operated outside the constraints that had hampered imperial troops. Recruitment emphasized personal allegiance over institutional discipline, and command structures reflected local hierarchies rather than imperial bureaucracy. While these forces proved militarily successful against the Taiping, their emergence fundamentally altered the balance between center and periphery.

Oversight of these militias was uneven at best and, in many cases, largely illusory. Paperwork, reporting, and legal accountability often lagged far behind events on the ground, if they existed at all. Provincial commanders exercised wide discretion in matters of punishment, requisition, and movement, frequently without prior authorization or subsequent review. The emergency conditions of rebellion insulated these actors from scrutiny, as effectiveness in suppressing insurgency came to outweigh adherence to legal norms. As a result, coercive practices varied dramatically across regions, creating a fragmented enforcement landscape in which legality was situational rather than systemic.

For civilians, delegated force produced an environment defined by uncertainty and exposure. Militia armies requisitioned food, seized property, conscripted labor, and punished suspected collaborators with little regard for formal judicial process. Villages caught between Taiping forces and provincial armies faced extortion, violence, and reprisal from both sides. Local commanders often treated civilian populations as resources to be exploited or threats to be neutralized rather than subjects to be protected. The distinction between protection and predation collapsed as militarized enforcement prioritized operational success over social stability.

In the Qing dynasty, reliance on provincial militias resolved the immediate military crisis but at a profound institutional cost. Delegated force preserved the dynasty by dispersing coercive power downward, yet it did so by eroding the legal and administrative foundations of centralized rule. Enforcement became effective but inconsistent, decisive but unrestrained. The state survived the Taiping Rebellion by relinquishing its monopoly on violence, creating a legacy in which militarized authority remained localized, personalized, and only loosely tethered to law long after the rebellion had ended.

Civilians between Armies: The Human Cost of Fragmented Authority

For civilians living in Taiping-era China, the delegation of force translated into pervasive vulnerability. As authority fractured, populations found themselves caught between competing armed actors whose claims to legitimacy were incompatible yet equally coercive. Taiping forces demanded allegiance, labor, and resources in the name of their alternative political and religious order. Provincial militias, operating under Qing authorization but without consistent oversight, imposed their own requisitions and punishments. In many regions, survival depended less on loyalty than on the ability to navigate overlapping and often contradictory demands.

The absence of a single, enforceable legal authority intensified civilian suffering. Villages were repeatedly stripped of grain, livestock, and labor by successive armies, each asserting necessity as justification. Suspected collaboration, whether real or fabricated, invited retaliation, while courts ceased to function or deferred to military command. Legal protection collapsed into discretion.

Fragmented authority also eroded social trust within communities. Forced recruitment, denunciation, and collective punishment incentivized betrayal and silence alike. Families concealed resources, fled ancestral lands, or aligned temporarily with whichever force promised momentary protection. Yet such alignments offered no durable security. The shifting presence of militias and rebel units meant that yesterday’s accommodation could become tomorrow’s evidence of treason. The constant recalibration required for survival imposed psychological as well as material costs, hollowing out the social fabric that had sustained local order.

The human cost of fragmented authority exposes the deeper consequences of delegating coercion without restraint. Civilian suffering did not arise solely from battlefield violence or ideological extremism. It emerged from the disappearance of a system capable of distinguishing protection from predation. When no authority could credibly enforce law across space and time, violence ceased to be episodic and became ambient, structuring daily life through anticipation rather than event. Fear replaced predictability as the organizing principle of civilian existence. The experience of ordinary people thus provides the clearest evidence that internal policing, once unmoored from legal reach, transforms security from a promise of order into a condition of permanent exposure.

Law without Reach: The Erosion of Legal Restraint

As the Taiping conflict intensified, Qing law did not disappear, but it lost reach. Statutes, procedures, and expectations of bureaucratic accountability formally remained in place, yet they no longer structured behavior on the ground. Legal authority depended on transmission, documentation, and review, all of which presupposed administrative stability. Under conditions of sustained rebellion and delegated enforcement, these mechanisms faltered. Law continued to exist as text and ideal, but it ceased to function as an effective constraint on those wielding force.

Delegation accelerated this erosion. Provincial militias and irregular armies operated at a distance from the documentary practices that had once linked local action to imperial oversight. Commanders exercised punitive authority without standardized investigation, warrant, or review. Decisions were made in real time, justified by urgency rather than procedure. Even when abuses were reported, the sheer volume of violence and the priority placed on suppression rendered meaningful review unlikely. Legal restraint became retrospective and symbolic, invoked after the fact to rationalize actions already taken rather than to guide them in advance.

This breakdown altered the relationship between legality and legitimacy in fundamental ways. Officials and commanders learned quickly that effectiveness insulated them from scrutiny, while adherence to procedure risked delay, exposure, or failure. Over time, enforcement norms adjusted to these incentives. Coercion became credible not because it followed law, but because it produced immediate and visible results. The distinction between lawful punishment and expedient violence blurred, then dissolved entirely. Legal language persisted, but it functioned primarily as a vocabulary of justification rather than a framework of decision-making. Law no longer mediated between state and subject. It followed force, conferring a veneer of order on actions already carried out, while abandoning any meaningful role in shaping how coercion was applied.

The erosion of legal reach marked a decisive transformation in governance. The state survived by tolerating, and often endorsing, enforcement unmoored from its own legal traditions. This accommodation did not simply reflect wartime necessity. It redefined the role of law within the imperial system, converting it from a framework of restraint into a language of justification. Once law lost the capacity to limit coercion, internal policing ceased to be a function of governance and became a substitute for it.

Militarized Order and the Seeds of Long-Term Fragmentation

The suppression of the Taiping Rebellion restored a measure of territorial stability, but it did so by entrenching militarization within Qing governance. Provincial armies that had been raised as emergency measures were not fully dismantled once the immediate threat receded. Instead, they remained embedded in local power structures, retaining influence over taxation, security, and administration. What emerged was a form of order sustained less by centralized law than by the continued presence of armed force tied to regional authority.

This transformation altered the balance between the imperial center and the provinces in lasting ways. Officials who had successfully mobilized militias gained political capital and autonomy, often eclipsing the authority of civil administrators. Loyalty flowed increasingly toward commanders rather than institutions, and governance became personalized rather than procedural. The court, having relied on these figures for survival, found itself constrained in reasserting control without risking renewed instability.

Militarized order also reshaped expectations about how authority functioned, both within the state and among the population it governed. The experience of rebellion taught officials that decisive action, rather than procedural fidelity, was the primary measure of effective rule. For civilians, the lesson was more sobering: security was delivered by those with arms, not by abstract legal guarantees. Even after large-scale conflict ended, administrative decisions were made with the assumption that coercion might be required to secure compliance. This expectation narrowed the space for negotiation and eroded confidence in legal remedies, particularly in regions where imperial oversight had already weakened. The legacy of rebellion thus recalibrated political culture, normalizing discretionary enforcement as a permanent feature of governance.

For civilians, the post-Taiping landscape offered little relief. Although large-scale fighting subsided, the structures that had produced vulnerability persisted. Local armies continued to requisition resources, enforce discipline, and suppress dissent with minimal oversight. The memory of wartime violence lingered, shaping behavior through anticipation rather than direct experience. Stability existed, but it was stability conditioned by fear and habituation to militarized authority.

In the aftermath of the Taiping Rebellion, the dynasty confronted a paradox of survival. The state endured, yet the means by which it preserved itself undermined the coherence of centralized rule. Delegated militarization fractured administrative uniformity, entrenched regional power, and weakened the credibility of law as a binding force. What appeared as restored order concealed a deeper fragmentation, one that limited the court’s capacity to govern without coercion. Militarized internal policing, once normalized, proved resistant to reversal. The seeds planted during the rebellion would continue to shape Qing governance, leaving a polity intact in appearance but increasingly hollowed out in practice.

Conclusion: When Delegation Replaces Authority

The Qing suppression of the Taiping Rebellion reveals a pattern of state survival that carries profound institutional costs. Faced with an existential threat, the dynasty preserved itself not by strengthening centralized authority but by dispersing coercive power outward. Delegation became the mechanism through which order was restored, yet this restoration depended on abandoning long-standing assumptions about legal restraint, bureaucratic oversight, and the state’s monopoly on violence. What emerged was not a temporary wartime deviation, but a structural transformation in how authority functioned.

By empowering provincial militias and irregular armies, the Qing state resolved the immediate military crisis while simultaneously weakening its own governing foundations. Force proved effective precisely because it operated beyond procedural constraint. Yet this effectiveness came at the expense of coherence and accountability. Law no longer structured enforcement; it followed it. Authority ceased to flow uniformly from the center and instead became localized, contingent, and personalized. Delegation replaced command, and survival displaced legality as the organizing principle of governance.

This transformation reshaped the lived experience of power. For officials, success was measured by suppression rather than adherence to legal norms. For civilians, protection became uncertain and conditional, dependent on proximity to armed actors rather than on enforceable rights. The state remained present, but unevenly so. Its capacity to arbitrate between protection and predation eroded, leaving populations exposed to violence justified in the name of order but unbounded by law. Internal policing thus shifted from a function of governance to a substitute for it.

The Taiping Rebellion therefore stands as a cautionary episode in the history of state power, not simply for its scale of violence but for the institutional lessons it reveals. It demonstrates that delegation of force without legal restraint does more than escalate brutality in the short term. It reorders the relationship between law, authority, and legitimacy in ways that persist long after the crisis has passed. When order is built on delegated coercion, stability becomes dependent on continued fragmentation, as the center loses the capacity to govern without recourse to force. The Qing dynasty survived its greatest internal challenge, but the manner of its survival hollowed out the authority it sought to defend. What remained was a state intact in form yet weakened in substance, its endurance purchased at the cost of legal coherence and centralized control.

Bibliography

- Boardman, Eugene P. “Christian Influence upon the Ideology of the Taiping Rebellion.” Far Eastern Quarterly 10:2 (1951): 115-124.

- Brady, Tim. “Cross-Cultural Underpinnings of the Taiping Rebellion: Potential Modern Applications.” Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research 4:1 (1993): 7-13.

- Kuhn, Philip A. Rebellion and Its Enemies in Late Imperial China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- —-. Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Leung, Janice Y. “A Critique of Marx’s View of the Taiping Rebellion and Its Origins.” Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History 3:2 (2013): 48-52.

- MacCormack, Geoffrey. The Spirit of Traditional Chinese Law. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996.

- Mao, Bincheng. “Mob Ideology or Democracy: Analyzing Taiping Rebellion’s Defeat and Revolution of 1911’s Triumph in Ending the Qing Dynasty.” Swarthmore Undergraduate History Journal 2:1 (2021): 17-27.

- Platt, Stephen R. Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2012.

- Reilly, Thomas H. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.

- Rowe, William T. China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Spence, Jonathan D. God’s Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996.

- Wakeman, Frederic, Jr. The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Wright, Mary C. The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism: The T’ung-Chih Restoration, 1862–1874. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.26.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.