The legacy of this sequence shaped the relationship between state and citizen long after the barricades were cleared.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Defeat, Fear, and the Turn Inward

The collapse of French power in 1870–1871 produced more than military defeat. It generated a crisis of authority that reached deep into the fabric of the state. The fall of the Second Empire, the siege of Paris, and the humiliation of occupation by Prussian forces left France politically unmoored. Republican government emerged not through constitutional consolidation but through emergency improvisation, sustained by fear of collapse rather than confidence in legitimacy. In this context, the problem confronting the new regime was not simply how to govern, but how to assert sovereignty in the absence of settled authority.

Paris stood at the center of this crisis, both symbolically and materially. The city had endured months of siege, starvation, and bombardment, experiences that radicalized political consciousness and deepened distrust toward national authority. Workers, artisans, National Guardsmen, and political clubs increasingly viewed the defense of Paris as inseparable from the defense of republican and social ideals. When the National Assembly withdrew to Versailles and attempted to disarm the capital, the move was widely perceived as a betrayal rather than a restoration of order. The declaration of the Commune in March 1871 thus emerged from a context of shared sacrifice and political mobilization, presenting itself as a legitimate expression of popular sovereignty. For the government at Versailles, this claim represented not a policy dispute but a direct challenge to the state’s exclusive right to command and enforce authority.

The response of the French Third Republic was shaped by this perceived existential threat. Rather than negotiating the boundaries of authority through law or constitutional process, the government turned to force as the primary instrument of restoration. The decision to suppress the Commune militarily was made before the Republic itself possessed a stable constitutional foundation. Violence preceded legality. The use of the army against civilians was framed as the reestablishment of order, yet it occurred in a legal gray zone where emergency necessity substituted for formal authorization.

What follows argues that the suppression of the Paris Commune, culminating in the Bloody Week of May 1871, reveals how republican governments can rationalize internal violence ahead of constitutional clarity. Thousands of Parisians were killed or executed without due process in the name of restoring order, not as an accidental excess but as a deliberate strategy of pacification. The repression functioned as a foundational act, asserting state sovereignty through force before it could be articulated through law. By examining the political vacuum following defeat, the logic of restoration embraced by the Versailles government, and the retroactive construction of legality after repression, this study shows how state power turned inward. The result was not merely the destruction of the Commune but the creation of enduring political fractures, embedding trauma, mistrust, and memory into the foundations of the French Republic itself.

France after Defeat: Political Vacuum and Competing Claims to Authority

France in early 1871 existed in a condition of political suspension. The collapse of the Second Empire following military defeat by Prussia left no settled constitutional order to inherit power. The Government of National Defense that emerged during the siege of Paris governed provisionally, improvising authority amid occupation, armistice negotiations, and territorial loss. Sovereignty was asserted rhetorically but lacked institutional depth. In this vacuum, legitimacy depended less on law than on claims of necessity and survival.

The National Assembly elected in February 1871 did little to resolve this instability and, in important respects, deepened it. Its composition reflected a country traumatized by war and eager for peace, even at the cost of political compromise. Monarchists and conservatives dominated its ranks, while republican radicals were disproportionately concentrated in Paris. This imbalance fostered mutual suspicion between the capital and the Assembly. When the legislature relocated to Versailles, the move carried heavy symbolic weight. It suggested retreat, distance, and distrust of Paris itself. For many Parisians, Versailles came to represent not continuity of state authority but its alienation from the city that had borne the siege in the name of the Republic.

Paris, meanwhile, occupied a unique political position. The city had borne the brunt of the siege, organized its own defense, and armed large segments of its population through the National Guard. These experiences fostered a sense of civic entitlement grounded in participation rather than delegation. Authority in Paris was increasingly conceived as something generated locally through collective action, not imposed from a distant legislature whose legitimacy appeared compromised by defeat and concession.

The armistice with Prussia intensified these tensions and sharpened competing claims to authority. Many Parisians interpreted the peace as capitulation, achieved without their consent and at the expense of republican honor. The Assembly’s willingness to accept harsh terms, including territorial loss and massive indemnities, reinforced the belief that national authority was acting against the interests of those who had resisted longest. Political disagreement thus hardened into moral judgment. Competing visions of sovereignty emerged: one rooted in electoral legality, order, and acceptance of defeat; the other grounded in popular mobilization, sacrifice, and continued resistance. Neither possessed unambiguous constitutional grounding, yet both claimed to speak for the nation.

In this fractured landscape, the question was not whether authority existed, but which authority would prevail. The provisional character of governance in France meant that power was asserted through action rather than settled law. Political legitimacy became performative, demonstrated through control rather than consent. The Commune would emerge from this contest not as an aberration or mere insurrection, but as one claimant among several in a struggle to define who embodied the Republic after defeat. The subsequent suppression of that claim would therefore represent not the defense of an established constitutional order, but the violent imposition of one still in the process of being made.

The Paris Commune: Revolutionary Governance and Civic Mobilization

The Paris Commune emerged in March 1871 as an assertion of political authority grounded in popular participation rather than inherited sovereignty. Its leaders framed the Commune not as a provisional rebellion or temporary insurrection, but as a legitimate form of republican governance arising from extraordinary circumstances. Authority was claimed through election, public deliberation, and the visible involvement of armed citizens organized within the National Guard. These claims drew directly on the experience of siege, deprivation, and collective defense, which Communards interpreted as proof of civic virtue and political entitlement. In contrast to the distant Assembly at Versailles, the Commune presented itself as immediate, accountable, and embedded in the daily life of the city, embodying a conception of sovereignty rooted in presence rather than abstraction.

Governance under the Commune combined improvisation with ideological ambition. Communards enacted measures aimed at social justice and civic autonomy, including the suspension of rents accumulated during the siege, reforms to labor conditions, and the assertion of municipal independence. These actions were not merely symbolic. They reflected a broader vision of the Republic as a federation of self-governing communities rather than a centralized state. Administration was often uneven and constrained by time and resources, yet it was animated by a belief that legitimacy flowed upward from citizens rather than downward from institutions.

Civic mobilization was central to this project. The National Guard functioned simultaneously as a military force and a political body, blurring distinctions between civilian and soldier. Clubs, assemblies, and newspapers proliferated, fostering intense public debate over the meaning of republicanism, citizenship, and authority. Participation became a form of political validation. To supporters, the Commune represented the Republic in its most authentic form, defended by those who had suffered for it. To opponents, this same mobilization appeared chaotic, illegitimate, and dangerously subversive.

The existence of the Paris Commune thus crystallized competing conceptions of order within post-imperial France. It claimed authority through immediacy, participation, and collective sacrifice, challenging a state that relied on electoral legality without a settled constitutional foundation. This challenge was intolerable to the Versailles government not simply because of the Commune’s policies, but because of what it represented: an alternative source of sovereignty that bypassed centralized control. The suppression that followed would therefore aim not only to defeat an armed movement, but to extinguish a rival theory of republican legitimacy. In this sense, the Commune’s fate was sealed less by its military weakness than by the existential threat it posed to the state’s claim to exclusive authority.

The Versailles Government and the Logic of Restoration

The government established at Versailles conceived its task not as mediation but as restoration. In the wake of defeat and political collapse, officials understood order as something that had been lost and therefore had to be reimposed. The Commune was framed not as a rival political authority born of extraordinary circumstances, but as a rupture in the social fabric that threatened to dissolve the state altogether. From this perspective, compromise appeared less as prudence than as abdication.

Fear played a central role in shaping this logic. The memory of revolutionary upheaval, combined with anxieties about social disorder and national disintegration, encouraged a reading of the Commune as an existential danger. Ministers and deputies depicted Paris as a city seized by criminality and fanaticism, a space in which lawful authority had been suspended by mobs rather than reconstituted through civic action. This framing transformed political conflict into a question of policing. Once the Commune was defined as illegitimate by nature, the use of force became not merely permissible but obligatory.

The absence of a settled constitutional framework further enabled this turn toward repression. The republican regime governing from Versailles lacked a finalized constitution and operated under provisional legal arrangements, yet it asserted continuity with the state as an abstract and indivisible entity. Authority was justified through electoral mandate and national representation even as the precise limits of governmental power remained undefined. In this environment, legitimacy was enacted rather than codified. The capacity to suppress disorder became a substitute for constitutional clarity, with coercion functioning as proof of sovereignty. Restoration thus preceded consolidation, and violence served as the mechanism through which authority would later be formalized.

Military force emerged as the preferred instrument of this strategy, not as a last resort but as a deliberate choice. The army was charged not only with retaking Paris but with reasserting the primacy of centralized command over civic mobilization and local autonomy. Soldiers were deployed as internal enforcers, operating against civilians in densely populated urban space. Commanders were granted broad discretion, and judicial safeguards were sidelined in favor of speed and decisiveness. The reliance on overwhelming force reflected the government’s belief that hesitation would invite further rebellion. Restoration, in this logic, demanded visible domination rather than negotiated settlement.

This logic culminated in a campaign aimed at erasing the Commune as a political possibility rather than addressing its claims. The government sought not merely to defeat an armed adversary, but to demonstrate conclusively that sovereignty resided exclusively with the state and could not be contested from below. The suppression was therefore pedagogical as well as punitive, designed to deter future challenges by making an example of Paris. Restoration, as conceived at Versailles, was less about repairing constitutional order than about imposing it through force. The violence that followed would be justified as necessity, yet it flowed directly from a political decision to equate order with suppression and legality with victory.

Bloody Week: Military Suppression and the Collapse of Due Process

The retaking of Paris in May 1871 marked the violent culmination of the Versailles government’s logic of restoration. As government troops entered the city, the objective was not limited to reestablishing territorial control. It was to extinguish the Commune as a political fact. The campaign unfolded with extraordinary speed and brutality, reflecting a decision to prioritize decisive force over legal process. Urban space became a battlefield in which distinctions between combatant and civilian rapidly dissolved.

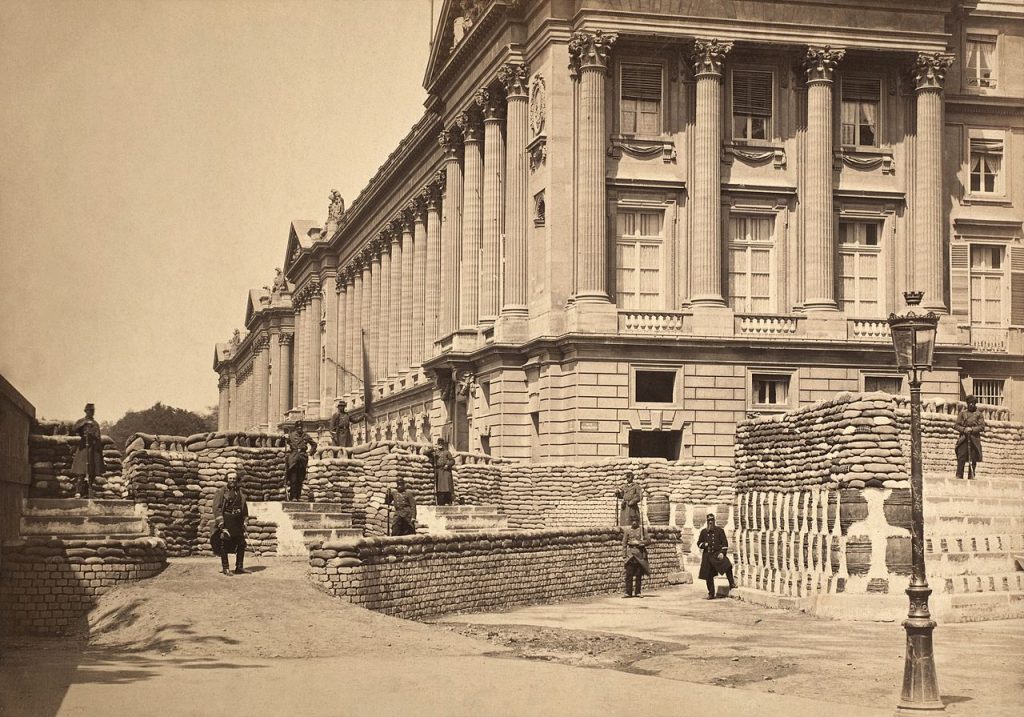

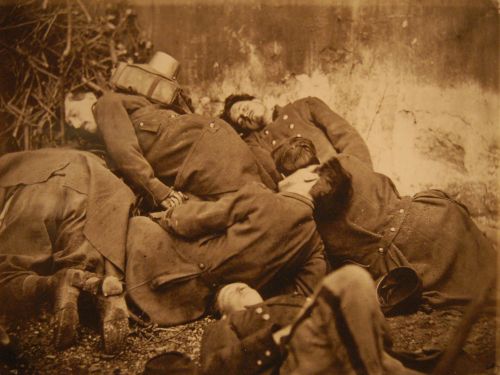

Military operations during Bloody Week were conducted as internal war rather than law enforcement, and this distinction shaped every aspect of the repression. Barricades were stormed street by street, often with artillery support, transforming residential neighborhoods into zones of annihilation. Resistance, whether armed or merely suspected, was met with immediate execution. Soldiers were authorized to act on appearance, location, and association rather than evidence. Summary killings became routine not because discipline failed, but because discretion was encouraged. The absence of clear rules of engagement turned pacification into eradication. Violence was not an unintended excess of battle. It was an accepted and anticipated instrument of restoration.

Due process collapsed almost immediately. Arrests were carried out en masse, often without formal charges or identification. Suspected Communards were executed on the spot or marched to improvised detention sites where military authority supplanted judicial review. Courts ceased to function as mediating institutions. The legal distinction between accusation and guilt vanished, replaced by a logic in which presence itself became incriminating. Law was neither suspended nor formally repealed. It was rendered irrelevant by speed and scale.

The targeting of civilians was not incidental to this process but integral to its logic. Residents of working-class districts were treated as presumptive collaborators, and entire neighborhoods were subjected to collective punishment. The violence followed social and political geography, concentrating in areas associated with radical politics and popular mobilization. Women were accused of incendiary activity, children were caught in crossfire and reprisals, and the elderly were executed as alleged accomplices. The aim was not merely to defeat armed resistance but to terrorize the social base from which the Commune had drawn legitimacy. Order was restored not through adjudication or reconciliation, but through exemplary violence designed to erase political possibility.

What distinguished Bloody Week was not only the magnitude of killing, but the state’s willingness to accept extrajudicial violence as legitimate governance. Commanders exercised near-total discretion, and accountability was deferred indefinitely in the name of necessity. The army functioned as a sovereign actor within Paris, enforcing authority through force without meaningful civilian oversight. Military success itself became evidence of legitimacy. The Republic asserted its right to rule by demonstrating its capacity to kill at scale, substituting coercive finality for constitutional clarity and allowing force to precede law as the foundation of order.

Bloody Week thus represents a decisive moment when state power turned inward and law yielded to restoration by violence. The suppression of the Commune did not occur within an established legal framework. It preceded one. Due process was not temporarily strained but fundamentally displaced. By the time legality was reconstructed, the outcome had already been decided by force. The Republic survived, but it did so by founding its authority on bloodshed that law would later be asked to explain rather than prevent.

Law after Violence: Retroactive Legality and State Justification

In the aftermath of Bloody Week, the French state moved swiftly to reconstruct legality around faits accomplis. Courts, commissions, and administrative procedures were reactivated not to determine whether the violence had been lawful, but to organize its consequences. Trials of alleged Communards proceeded on a massive scale, accompanied by deportations, long prison sentences, and civic exclusions. Legal processes functioned as instruments of classification and containment, transforming mass repression into an administratively legible outcome. Law returned not as a check on state power, but as a mechanism for stabilizing a political victory already secured through force.

This retroactive turn reshaped the function of judicial process itself. Proceedings emphasized affiliation, presence, and presumed intent rather than demonstrable criminal acts. Guilt was inferred from association with the Commune, residence in certain neighborhoods, or service in the National Guard. Evidentiary standards were loosened to accommodate political objectives, and legal categories were stretched to fit the needs of consolidation. Courts became extensions of executive will, tasked with confirming outcomes rather than testing claims. The appearance of legality mattered deeply, but its substance was subordinated to the imperative of closure. Sovereignty had been settled on the barricades; law was required to narrate that settlement as justice.

Amnesty, when it eventually arrived, underscored this asymmetry. Framed as an act of state mercy rather than acknowledgment of excess, it reinforced the premise that repression had been justified by necessity. Clemency functioned not as correction, but as confirmation of authority after victory.

Within France, the post-Commune legal settlement thus completed a transformation initiated during Bloody Week. Law did not reassert control over force; it adapted to it. By reconstructing legitimacy after violence, the state embedded repression into its legal memory, insulating the Republic from accountability while presenting order as restored. The result was a durable but compromised legal culture, one in which law functioned less as a safeguard against internal violence than as its retrospective justification.

Political Memory, Trauma, and Enduring Division

The violence of Bloody Week did not end with the restoration of state control. It imprinted itself on French political memory as a wound that resisted closure and resisted assimilation into a unifying national narrative. For survivors and sympathizers of the Commune, the killings, executions, and deportations became enduring markers of betrayal, evidence that the Republic had been founded through the annihilation of its own citizens. Memory operated not as a neutral record but as a moral ledger, preserving injustice where official history offered resolution. The dead of the Commune were not merely casualties of conflict; they became symbols of a Republic willing to sacrifice legality and solidarity in the name of order.

The state, by contrast, pursued a strategy of selective remembrance. Official narratives framed the suppression as a tragic but necessary act, emphasizing the restoration of order while minimizing the scale of civilian suffering. Commemoration was constrained, and public acknowledgment of excess remained limited. This asymmetry produced a politics of silence in which trauma persisted without recognition. What could not be publicly mourned was instead transmitted through families, neighborhoods, and political subcultures, sustaining alternative histories beneath the surface of official republican identity.

These divergent memories hardened into durable political divisions that shaped the trajectory of French politics well beyond the nineteenth century. Working-class movements, socialist organizations, and later labor parties inherited the Commune as both inspiration and warning: proof that radical democratic possibility existed, and proof of how violently it could be crushed. For the state and conservative forces, Bloody Week became an unspoken precedent, a demonstration that decisive repression could secure survival. Each side internalized a different lesson, reinforcing mutual distrust and competing conceptions of legitimacy. Memory thus became a site of political inheritance, transmitting conflict across generations rather than resolving it.

Trauma also shaped political behavior in less visible ways. Fear of renewed repression influenced strategies of protest and organization, while fear of renewed insurrection influenced policing and security doctrine. The Commune lingered as an unspoken reference point, invoked implicitly whenever the boundaries of dissent were tested. The legacy of Bloody Week conditioned expectations on both sides of the barricades, narrowing the space for compromise and amplifying the stakes of political conflict.

Within France, the suppression of the Commune produced not reconciliation but a fractured political culture whose divisions proved remarkably durable. The Republic endured, yet it carried within it unresolved memories of internal war that shaped how authority was asserted and contested. Political order was stabilized, but at the cost of embedding suspicion, grievance, and fear into the relationship between state and citizen. Bloody Week demonstrates that internal repression, even when successful in restoring control, leaves a residue that law and time alone cannot erase. The trauma endured not as a relic of the past, but as an active force shaping the limits of republican trust.

Conclusion: When Order Precedes Legitimacy

The suppression of the Paris Commune reveals a recurring dynamic in moments of acute state crisis: when authority is uncertain and legitimacy unsettled, governments often seek resolution through force rather than law. In 1871, the French Third Republic confronted a direct challenge to its sovereignty before it had fully constituted itself as a stable constitutional regime. Faced with competing claims to authority, one grounded in electoral representation and the other in popular mobilization, the state chose restoration through violence rather than adjudication through political or legal process. Order was asserted first, and legitimacy was constructed afterward. The Bloody Week thus stands not as an aberration or breakdown of republican principle, but as a formative episode in which coercion substituted for constitutional settlement.

This choice carried immediate and long-lasting consequences for the nature of republican governance. By privileging decisive repression over legal restraint, the Republic demonstrated that sovereignty could be asserted retroactively, with law arriving only after outcomes had been secured by arms. Due process did not fail because it was explicitly repudiated, but because it was subordinated to the perceived necessity of survival. Courts, statutes, and amnesties followed violence rather than shaping it. The result was a political order stabilized through fear and finality, in which legality functioned less as a constraint on power than as a narrative device used to justify its exercise after the fact. Authority was proven by success, not by procedure.

The legacy of this sequence shaped the relationship between state and citizen long after the barricades were cleared. The memory of Bloody Week entrenched mistrust among working-class movements and reinforced a security logic within the state that equated dissent with threat. Internal policing became thinkable as an instrument of republican defense, even when directed against civilians. In France, the Commune’s destruction thus narrowed the space for democratic contestation, embedding repression into the foundations of order.

Ultimately, the Paris Commune demonstrates the costs of founding legitimacy on force. Order achieved in advance of law may endure, but it does so by hollowing out the principles it claims to protect. When states resolve crises by turning inward against their own populations, they secure control at the expense of trust and consent. The lesson of 1871 is not simply that violence can restore order, but that the order it restores is permanently marked by the conditions of its birth.

Bibliography

- Bourque, Stephen. “Rouen: La Semaine Rouge.” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 14:3-4 (2012): 1-34.

- Furet, François. Revolutionary France 1770–1880. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

- Gould, Roger V. “Multiple Networks and Mobilization in the Paris Commune, 1871.” American Sociological Review 56:6 (1991): 716-729.

- Harison, Casey. “The Paris Commune of 1871, the Russian Revolution of 1905, and the Shifting of the Revolutionary Tradition.” History and Memory 19:2 (2007): 5-42.

- Hazareesingh, Sudhir. The Legend of Napoleon. London: Granta, 2004.

- Horne, Alistair. The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870–71. London: Penguin, 1965.

- Johnson, Martin P. “Memory and the Cult of Revolution in the 1871 Paris Commune.” Journal of Women’s History 9:1 (1997): 39-57.

- Merriman, John. Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune of 1871. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Nay, Julie C. and Dr. Daryle Lee. “Sites of Memory: The Destruction of Public Buildings During the Paris Commune of 1871.” Journal of Undergraduate Research 1:767 (2013): 1-2.

- Nora, Pierre. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

- Payne, Howard C. “An Early Concept of the Modern Police State in Nineteenth Century France.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 43:3,18 (1952): 377-381.

- Rougerie, Jacques. Paris Libre, 1871. New York: Seuil, 2004.

- Tombs, Robert. The Paris Commune 1871. London: Longman, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.26.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.