The history traced here suggests that repetition is not a symptom of cultural decay but a structural condition of cultural endurance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Art Became Suspicious

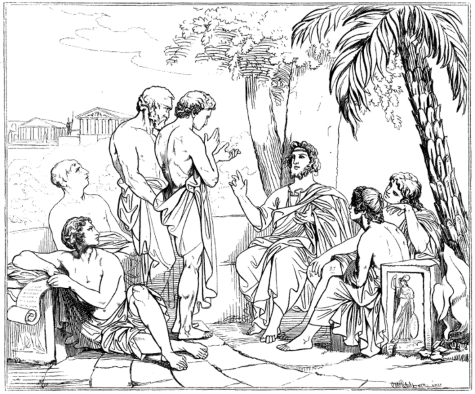

In classical Athens, artistic production was not peripheral to civic life but one of its central organizing forces. Poetry shaped moral imagination, drama educated citizens in public virtue and failure, and visual art structured how the world was seen, remembered, and judged. Homer was not merely literature but pedagogy, recited, memorized, and treated as an ethical authority. Tragedy was not entertainment alone but a shared moral language through which Athenians processed war, loss, justice, divine punishment, and human limitation. Festivals such as the City Dionysia embedded imitation into the rhythms of political life, bringing citizens together to watch familiar stories reenacted with emotional force. Art did cultural work. It instructed, moved, unified, and disciplined. It was precisely this formative power that made it worthy, and dangerous, in Plato’s eyes.

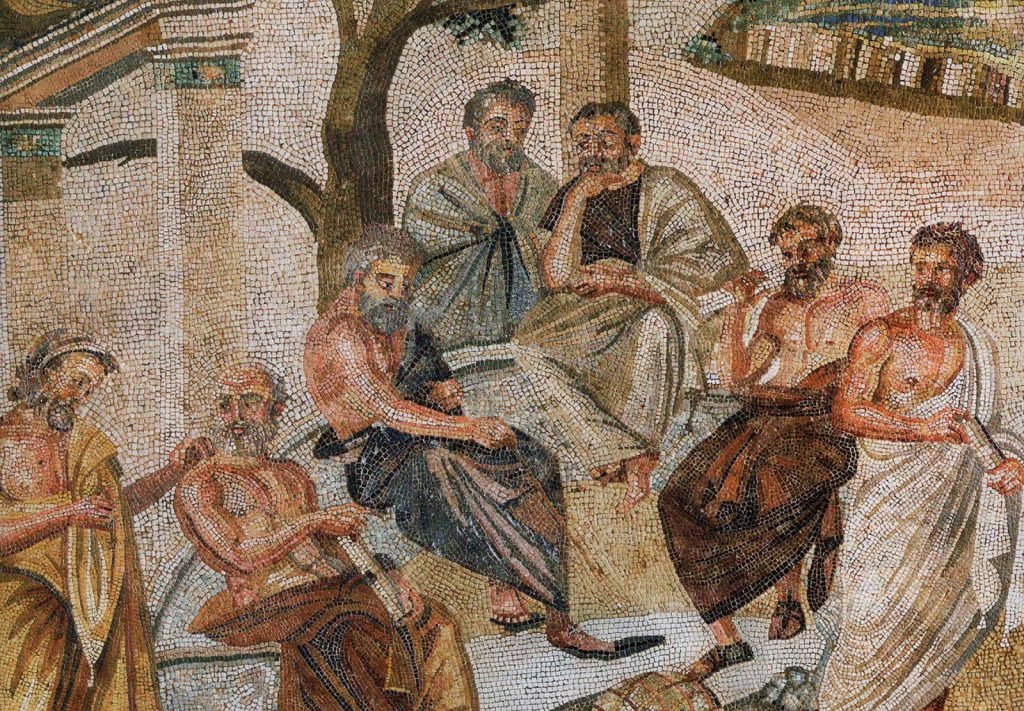

Plato’s attack on mimesis emerged from within this dense cultural environment. By the fourth century BCE, Athens was saturated with performance, repetition, and familiar narrative forms. Myths circulated constantly, dramatic conventions were widely understood, and audiences were trained to respond quickly and intensely to recognizable emotional cues. For Plato, this success posed a problem. When imitation becomes effortless and ubiquitous, does it cultivate judgment or replace it.

At stake was not merely the accuracy of representation but the orientation of the soul. Plato worried that mimetic art trained citizens to feel without understanding, to sympathize without reflection, and to mistake emotional resonance for truth. Art, in his account, operated at a distance from reality, offering images of appearances rather than engagement with what truly is. When such representations multiplied, they risked crowding out philosophical inquiry, replacing the difficult labor of reasoning with the easy pleasures of recognition and emotional familiarity. Cultural abundance, in this view, threatened to become cultural noise, pleasing but empty, persuasive but unmoored from ethical discipline.

Plato’s intervention did not signal cultural collapse. Greek society did not abandon art, nor did philosophy extinguish imitation. Instead, Plato’s critique marked a turning point in how creativity, truth, and authority were theorized. By making imitation suspect, he forced Greek thinkers to clarify standards, define depth, and distinguish between appearance and understanding. This essay argues that Plato feared not art itself, but imitation untethered from discipline. His anxiety belongs to a recurring historical pattern: moments when cultural production expands so rapidly that societies must renegotiate how meaning is preserved amid abundance.

Mimesis before Plato: Imitation as Education and Tradition

Before Plato recast mimesis as a philosophical problem, imitation functioned as a respected and productive mode of education in Greek culture. Learning was inseparable from copying. Young Greeks absorbed language, values, and social roles by memorizing and reenacting authoritative models, whether poetic, musical, or behavioral. Imitation was not understood as a failure of originality but as the primary mechanism through which excellence was transmitted. To imitate well was to align oneself with established standards of virtue, skill, and communal memory, ensuring continuity across generations rather than rupture.

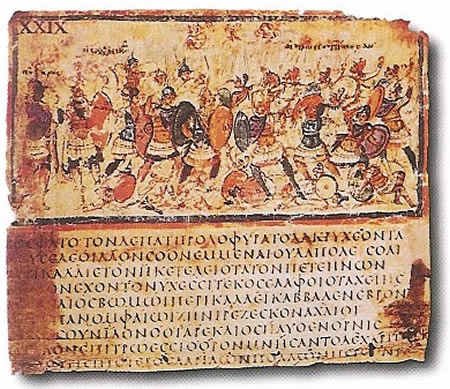

Homeric poetry stood at the center of this educational system and exerted an influence that extended far beyond literary appreciation. The Iliad and the Odyssey were not read silently but performed aloud, memorized through constant repetition, and treated as repositories of ethical, social, and practical wisdom. Heroes provided models for courage, restraint, loyalty, and error, while the gods illustrated the dangers of excess, pride, and disorder. To imitate Homer was not to parrot his verses mechanically, but to internalize a moral grammar through narrative. Cultural formation depended on the assumption that wisdom could be learned through patterned repetition, embodied in story and example rather than abstract principle. In this sense, imitation was the medium through which ethical reasoning itself was cultivated.

Dramatic performance extended this mimetic pedagogy into the civic sphere. Tragedy and comedy staged familiar myths before mass audiences, inviting spectators to recognize, judge, and emotionally process shared narratives. Far from dulling thought, repetition sharpened communal reflection. Each performance reinterpreted inherited material, allowing audiences to test enduring themes against contemporary political and social concerns. Imitation here was dynamic rather than static. It assumed that meaning emerged through variation within continuity, not through the abandonment of tradition or the pursuit of novelty for its own sake.

Artistic training likewise relied on imitation as the foundation of mastery. Sculptors, painters, musicians, and athletes learned by copying established forms, proportions, rhythms, and techniques long before they were permitted to innovate. Skill was measured by fidelity to models that embodied ideal balance, harmony, and restraint. Only after prolonged submission to these standards could individual style emerge in a meaningful way. Innovation was therefore understood as refinement rather than rupture, an extension of tradition rather than a rejection of it. In this pre-Platonic framework, mimesis was not a threat to truth or creativity. It was the cultural mechanism that made both possible, anchoring individual expression within a shared symbolic, ethical, and aesthetic order.

Plato’s Philosophical Break: Copying as Distance from Truth

Plato’s critique of mimesis marked a decisive break from earlier Greek assumptions about imitation as a vehicle of education and continuity. Where his predecessors largely treated imitation as a means of transmitting excellence, Plato reframed it as a metaphysical problem. In doing so, he shifted the debate from pedagogy to ontology. The question was no longer whether imitation could teach, but whether it could ever convey truth. This reorientation placed artistic production within a hierarchy of reality in which appearance was fundamentally suspect.

At the center of Plato’s argument stood the theory of Forms, which radically reordered the value of representation. True knowledge, he maintained, concerned immutable, intelligible realities accessible only through reason, not perception. Physical objects already occupied a diminished status, participating imperfectly in the Forms and subject to change, decay, and error. Artistic representations compounded this distance. They imitated physical objects rather than the Forms themselves, producing images of appearances rather than encounters with essence. Art thus became a copy of a copy, twice removed from truth, offering plausibility without substance. For Plato, this was not a neutral descriptive claim but a serious philosophical indictment. The mimetic artist did not grasp the nature of what was represented, nor could such grasp be acquired through imitation alone.

This metaphysical distance carried profound epistemological consequences. Plato argued that mimetic art appealed to the senses and emotions rather than to reason, encouraging spectators to mistake recognition for understanding. A painted bed might appear convincing, but it conveyed nothing about the Form of Bedness or the knowledge required to construct or use a bed well. In dialogues such as the Republic and Ion, Plato insisted that poets and artists operated without genuine knowledge, guided instead by inspiration, habit, or audience expectation. Their success depended on resonance rather than truth. Because they could persuade without knowing, mimetic creators posed a unique epistemic threat. Imitation thus became dangerous not because it was false, but because it was convincing while remaining epistemically empty.

The problem was compounded by art’s social authority. Because poetry and drama were widely admired and emotionally compelling, they exercised influence disproportionate to their epistemic value. Plato feared that mimetic works trained citizens to respond emotionally to representations rather than rationally to reality. By repeatedly presenting familiar narratives and stock characters, art cultivated recognition rather than inquiry. This habituation, he argued, dulled philosophical rigor and encouraged moral complacency. Copying did not merely distance audiences from truth; it trained them to be satisfied with that distance.

Plato’s philosophical break, then, lay in his refusal to grant imitation any intrinsic educational legitimacy. Where earlier Greek culture treated repetition as a means of preserving and refining wisdom, Plato treated it as a barrier to genuine understanding unless strictly subordinated to philosophy. Imitation was not condemned absolutely, but it was radically demoted. Only representations disciplined by reason and oriented toward truth could escape the charge of emptiness. In reframing mimesis as a problem of epistemology and ethics rather than tradition and pedagogy, Plato permanently altered the terms of cultural criticism. Creativity, authority, and meaning were no longer measured by continuity alone, but by their proximity to truth.

Moral Anxiety: Seduction, Emotion, and the Crowd

Plato’s anxiety about mimesis was not confined to metaphysics or epistemology. It was, at its core, a moral and political concern about how citizens were shaped. Art mattered because it trained feeling, and feeling, for Plato, shaped character. Poetry and drama did not merely represent actions. They invited audiences to inhabit them emotionally. By rehearsing passions publicly and repeatedly, mimetic art risked cultivating dispositions that reason was meant to govern rather than obey.

Central to this worry was the seductive power of performance and its capacity to reward emotional surrender. Tragic poetry, in particular, excelled at making suffering compelling and attractive. It invited spectators to sympathize with anger, grief, revenge, and despair, emotions Plato believed should be acknowledged but rigorously disciplined. When citizens learned to enjoy these emotions aesthetically, they risked carrying them into civic life without restraint. Art did not simply mirror moral weakness. It normalized it. By presenting intense feeling as pleasurable and meaningful in itself, mimetic culture trained audiences to value emotional intensity over ethical evaluation. What moved the soul most forcefully risked being mistaken for what was most worthy.

Plato was especially troubled by the way imitation operated on crowds rather than individuals. In the theater, emotional response became contagious. Spectators laughed, wept, and recoiled together, reinforcing shared reactions without requiring shared reasoning. This collective affect amplified art’s influence while diffusing responsibility. No single audience member needed to justify their response. Feeling became self-validating. For Plato, this posed a serious danger to rational self-governance, which depended on critical distance rather than immersion. The crowd felt as one, but it did not think as one.

This concern intersected directly with Plato’s political theory. A democratic audience, he feared, was particularly vulnerable to emotional manipulation because authority in such a system followed popularity rather than wisdom. Poets and performers succeeded not by instructing the soul toward truth but by pleasing the many. Mimetic art thus resembled rhetoric stripped of philosophical constraint, operating through charm, familiarity, and emotional gratification. It rewarded what was immediately satisfying rather than what was intellectually or morally demanding. Plato’s critique of mimesis echoed his broader suspicion of mass persuasion, where the power to move an audience could eclipse the responsibility to guide it well.

Repetition intensified these dangers by training emotional reflex rather than moral judgment. Familiar stories, archetypal characters, and predictable emotional arcs conditioned audiences to respond automatically. Recognition replaced deliberation. The pleasure of knowing what came next dulled the impulse to ask why it mattered or whether the response was appropriate. Over time, Plato worried, this habituation would erode moral seriousness, producing citizens fluent in feeling but unpracticed in judgment. Cultural abundance did not elevate virtue. It softened it, encouraging comfort, sympathy, and emotional release where discipline, restraint, and rational evaluation were required.

Yet even here Plato’s anxiety reveals the power he attributed to art rather than its triviality. Mimetic culture mattered precisely because it worked. It shaped souls efficiently, collectively, and invisibly. Plato’s fear was not that art was empty, but that it was effective without being accountable to reason or truth. Emotion untethered from philosophical discipline became a political force, capable of guiding behavior without reflection. In identifying this danger, Plato articulated one of the earliest critiques of mass culture: the worry that what moves the crowd most easily may also move it least wisely.

Cultural Saturation and the Fear of Formula

By the fourth century BCE, Athens had become a city saturated with cultural production to an unprecedented degree. Poetry, drama, music, and visual art circulated constantly, supported by religious festivals, competitive performances, and civic patronage that encouraged continual output. Myths were retold year after year, dramatic structures grew increasingly recognizable, and audiences learned to anticipate emotional arcs with ease. This was not a marginal phenomenon but a defining feature of Athenian public life. For Plato, such abundance was deeply unsettling. Cultural production had become reliable, efficient, and omnipresent. Art no longer struggled to be heard; it dominated attention. In this environment, Plato feared that imitation risked becoming automatic rather than reflective, pleasing rather than probing. Cultural success itself became suspect.

At the heart of this anxiety was formula. Tragedy relied on recognizable plots, archetypal figures, and recurring moral dilemmas. Comedy thrived on familiar social types and exaggerated repetition. These conventions allowed performances to succeed quickly, eliciting laughter, pity, fear, or outrage without demanding sustained philosophical engagement. Plato worried that such familiarity trained audiences to respond reflexively rather than critically. When recognition replaced inquiry, art ceased to provoke examination and instead confirmed expectations. The pleasure of knowing what kind of story one was watching, and how one was meant to feel, threatened to substitute emotional fluency for intellectual effort. Formula did not merely simplify art. It risked simplifying judgment itself.

This fear of formula extended beyond aesthetics into epistemology. Repeated narratives, Plato argued, could create the illusion of understanding without the labor of thought. When the same moral conflicts were staged again and again, audiences learned how to react without learning why those reactions were justified. Formula flattened difference, smoothing over ambiguity and complexity in favor of emotional clarity. In this sense, cultural saturation threatened to crowd out philosophy not by opposing it directly, but by occupying the cognitive and emotional space where questioning might otherwise occur. The familiar displaced the difficult, not through argument, but through saturation.

Plato’s concern also reflected anxiety about authority in a crowded cultural field. When artistic success depended on audience approval, creators were incentivized to reproduce what already worked. Innovation gave way to refinement of formula, and refinement risked sliding into repetition for its own sake. Standards governing cultural value became externalized, shaped by popularity rather than truth or ethical seriousness. In such an environment, Plato feared that serious inquiry would struggle to compete with what was immediately gratifying. Philosophy, slow and demanding, risked being drowned out by the constant hum of familiar representations that required no effort to consume and no discipline to enjoy.

This critique reveals a paradox. Plato’s fear of saturation testifies to the extraordinary vitality of Greek cultural life rather than its decline. Formula emerged because traditions were rich enough to sustain variation, and audiences were sophisticated enough to recognize it. Cultural abundance did not inherently erase meaning, but it did force thinkers to confront how meaning was distinguished from noise. Plato’s response was to demand sharper standards, clearer hierarchies, and stricter discipline. His anxiety about formula thus marked not the exhaustion of Greek creativity, but a moment when abundance compelled philosophy to define itself more rigorously against the seductions of repetition.

Plato’s Paradox: Philosophy as Anti-Mimesis

Plato’s attack on imitation is complicated by the literary form in which he conducted it. His philosophy does not arrive as abstract treatise but as dialogue, populated by characters, staged encounters, and dramatic tension. Socrates debates, provokes, and persuades in scenes that resemble the very mimetic practices Plato criticizes. This formal choice creates a paradox at the heart of his project. Philosophy defines itself against imitation while relying upon it. Plato did not abandon representation. He sought to discipline it.

The Platonic dialogue functions as a controlled form of mimesis, one carefully constrained by philosophical purpose and ethical intent. Unlike poetry or drama, which aim primarily to move audiences emotionally, dialogue is designed to provoke rational inquiry and self-examination. Characters speak not to be admired, pitied, or imitated emotionally, but to expose assumptions, contradictions, and false confidence through argument. The dramatic frame serves as a pedagogical structure rather than an aesthetic goal, guiding readers into an active role as participants in inquiry rather than passive recipients of feeling. Plato’s objection, then, was not to representation itself, but to representation untethered from standards of truth, reason, and responsibility.

This distinction allowed Plato to reclaim narrative while condemning aesthetic seduction. His dialogues imitate inquiry rather than emotion, modeling a process of questioning rather than a finished worldview. They stage philosophy as an activity rather than a doctrine, requiring readers to follow lines of reasoning, confront their own unexamined beliefs, and experience the discomfort of uncertainty. Readers are not invited to identify with Socrates as a tragic or heroic figure, but to test themselves against his method. In this way, Plato attempted to separate legitimate imitation from illegitimate copying, preserving mimesis as a tool of instruction while stripping it of its intoxicating power. Philosophy became an anti-mimesis that nonetheless depended on mimetic form to function.

The paradox is unresolved and productive. Plato never escaped the need for form, voice, and scene, nor did he fully wish to. Instead, he elevated certain forms while condemning others, drawing boundaries around what kinds of imitation could serve truth. This reveals that his deepest concern was not imitation as such, but control. Representation required governance. Creativity demanded discipline. By staging philosophy as dialogue, Plato acknowledged that human beings learn through example, encounter, and dramatized conflict, even as he warned against surrendering judgment to pleasure. His philosophy thus stands not outside mimesis, but in tension with it, redefining imitation as a means toward truth rather than an obstacle to it.

After Plato: Greek Culture Did Not Stagnate

Plato’s critique of mimesis did not arrest Greek cultural production. Nor did it inaugurate an era of aesthetic withdrawal or philosophical dominance over art. Instead, it sharpened debates about imitation, truth, and value, forcing subsequent thinkers to clarify what creativity was for and how it ought to be judged. Greek culture after Plato remained intensely productive, but it became more self-conscious about standards, purpose, and intellectual authority. Critique did not silence imitation. It refined it.

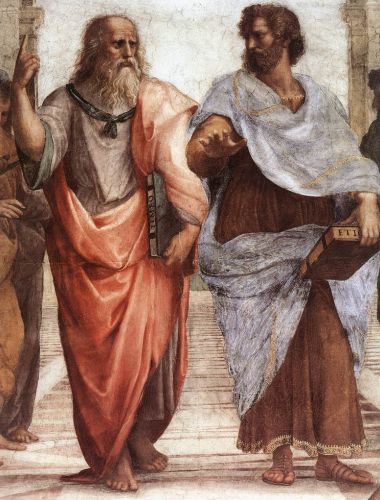

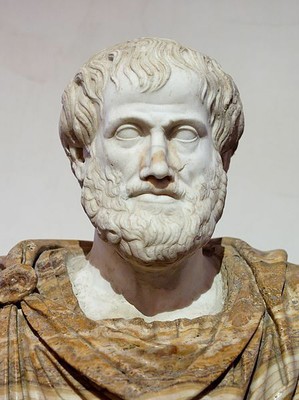

Aristotle’s response offers the clearest evidence of this transformation. In the Poetics, mimesis is not condemned but rehabilitated as a natural and cognitively valuable human activity. Aristotle argued that imitation is how humans learn, recognize patterns, and derive pleasure from understanding. Tragedy, far from being epistemically empty, reveals universal truths through particular cases by organizing action, character, and consequence into intelligible form. Where Plato feared that emotional engagement would overpower reason, Aristotle treated emotion as educable, capable of being structured toward insight through plot and recognition. This was not a rejection of Plato’s concerns, but a recalibration of them. The danger lay not in imitation itself, but in imitation without form, purpose, and proportion.

Beyond philosophy, Greek drama continued to evolve in response to heightened critical awareness. Later tragedians and comic poets worked within inherited conventions while becoming increasingly self-reflexive about them. Familiar myths were reframed with greater psychological depth, moral ambiguity, and ironic distance. Characters no longer functioned simply as exempla but as sites of tension between intention, circumstance, and consequence. Playwrights experimented with expectation, delayed recognition, and subverted familiar resolutions, encouraging audiences to reflect on the limits of moral certainty rather than simply affirming it. Cultural abundance did not produce stagnation. It generated sophistication by demanding that creators justify how and why they reused inherited material.

Scientific and historical writing likewise flourished in the post-Platonic world, often in deliberate conversation with mimetic critique. Thinkers such as Hippocrates and Thucydides explicitly distinguished their methods from poetic imitation while still borrowing narrative clarity, causal sequencing, and rhetorical discipline from literary forms. Thucydides’ history, for example, rejected mythic explanation but retained dramatic structure to convey the logic of human decision-making under pressure. Aristotle’s own biological and political writings adopted classificatory rigor while remaining attentive to exemplification and analogy. The result was not a clean separation between art and truth, but a diversification of intellectual practices, each articulating its own standards of credibility and meaning.

What followed Plato, then, was not cultural exhaustion but differentiation and maturation. Critique forced creators to justify their methods, audiences to sharpen their discernment, and thinkers to articulate why certain forms of imitation mattered more than others. Greek civilization did not abandon mimesis under philosophical pressure. It learned to live with it more deliberately, more critically, and with clearer expectations about what imitation could and could not do. Plato’s anxiety did not end creativity. It raised the stakes of creation by demanding more precise accounts of meaning, purpose, and truth in a world already rich with forms.

Mimesis and the Long History of Cultural Anxiety

Plato’s critique of mimesis was not an isolated philosophical episode but an early articulation of a recurring cultural anxiety that surfaces whenever cultural production accelerates. Societies repeatedly grow uneasy when imitation becomes widespread, efficient, and successful. Abundance provokes suspicion because it alters the relationship between creation and judgment. When art, stories, and images multiply rapidly, critics worry that repetition will crowd out depth, that familiarity will substitute for understanding, and that pleasure will overwhelm moral or intellectual discipline. Plato gave this anxiety a metaphysical vocabulary rooted in truth and being, but the emotional core of the fear is older and broader: that meaning becomes harder to defend when culture no longer feels scarce or difficult.

This pattern reappears whenever cultural forms become easier to produce, circulate, and consume. In the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, critics complained that Greek models were copied too faithfully, producing elegance without seriousness. Early Christian writers warned that classical imitation distracted believers from spiritual truth. With the rise of print in early modern Europe, commentators feared that books would overwhelm readers, encouraging shallow accumulation of knowledge rather than wisdom. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mass newspapers, popular novels, radio, and film each triggered renewed concerns about imitation, emotional manipulation, and cultural flattening. Each era framed its anxiety in its own terms, yet the core concern remained strikingly consistent: that imitation, once scaled, threatens to sever cultural production from ethical or intellectual depth.

What unites these anxieties is discomfort with scale rather than with imitation itself. Cultural production becomes troubling not when it exists, but when it succeeds too well. Repetition signals accessibility, but accessibility raises the problem of standards. If everyone can imitate, how is excellence preserved. If forms become familiar, how does one distinguish insight from noise. Plato’s suspicion of mimesis thus anticipates later critiques of popular culture, mass entertainment, and mechanical creativity. The fear is not that imitation exists, but that it becomes frictionless, operating without resistance or evaluative effort.

Yet history repeatedly demonstrates that such anxieties overestimate the fragility of meaning. Cultural abundance does not eliminate judgment. It redistributes it. As production scales, new forms of criticism, interpretation, and hierarchy emerge. Audiences learn to discriminate more finely, creators respond by refining technique, and intellectual communities articulate clearer criteria for value. The pressure of imitation forces cultures to become more explicit about what they prize and why. Anxiety, in this sense, functions less as a symptom of decay than as a catalyst for clarification.

Plato’s legacy illustrates this dynamic clearly. His attack on mimesis did not end imitation but sharpened philosophical standards, prompting Aristotle and others to theorize creativity more carefully. Later thinkers did not abandon art; they argued about it. They debated how imitation could teach, move, mislead, or discipline. The very persistence of mimetic anxiety testifies to its productive role. Each recurrence generates new distinctions, new vocabularies, and new defenses of meaning against the fear of emptiness.

Mimesis emerges not as a corrosive force but as a pressure point in cultural evolution. It exposes fault lines between pleasure and truth, abundance and judgment, access and authority. Societies return to these questions whenever cultural production accelerates and familiar forms threaten to overwhelm reflective evaluation. Plato was among the first to articulate the problem with philosophical rigor, but he was far from the last. His anxiety belongs to a long tradition of critical reflection that resurfaces precisely because imitation remains central to how humans learn, create, and remember. The fear endures not because culture is fragile, but because meaning must be actively defended whenever repetition makes creation easy.

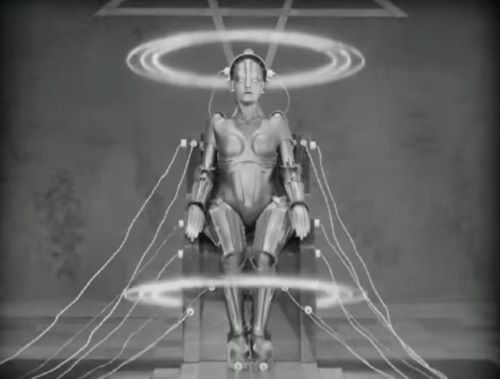

Generative AI and the Return of the Mimetic Fear

Contemporary debates over generative artificial intelligence revive, almost intact, the anxieties Plato articulated about mimesis. Trained on vast corpora of existing texts and images, generative systems produce outputs by identifying patterns and recombining familiar forms. Critics argue that such production lacks depth, intention, or understanding, yielding work that feels polished yet hollow. The complaint echoes Plato’s charge that imitation produces appearances without truth. What troubles observers is not merely that machines can generate content, but that they can do so fluently, at scale, and without the struggle traditionally associated with meaning-making.

At the center of this concern lies the fear of aesthetic abundance without judgment. When texts, images, and music can be generated effortlessly and endlessly, discernment risks being overwhelmed by volume rather than sharpened by difficulty. Much like Plato’s suspicion of poetic culture that pleased the crowd too easily, critics of AI worry that generative systems produce cultural “noise”: outputs that are competent, familiar, and emotionally legible but rarely demanding. The metaphor of “elevator music” captures this anxiety with precision. Creativity appears flattened into smooth repetition, offering recognition without challenge and comfort without consequence. What is feared is not error but saturation, a condition in which meaning is diluted not by falsehood but by excess.

This fear is sharpened by questions of authorship and authority. If a system can imitate styles, arguments, and genres convincingly, how does one distinguish understanding from mimicry. Plato worried that poets spoke without knowledge, guided by inspiration rather than reason. AI intensifies this worry by removing even the pretense of comprehension. Outputs can persuade without believing and argue without commitment, raising concerns about responsibility and accountability in public discourse.

Yet historical perspective complicates this alarm. As with earlier moments of mimetic anxiety, the problem may lie less in imitation itself than in misplaced expectations about what new technologies are meant to provide. Generative AI does not claim philosophical understanding or moral judgment. It operates as an infrastructural technology that reorganizes access to language, pattern, and memory. Like the scribal archive or the printed book, it multiplies the materials available for interpretation without replacing the need for human evaluation. The risk emerges when outputs are treated as authority rather than as provisional material to be questioned, contextualized, and revised. In this sense, the challenge is not technological but cultural: deciding where judgment properly resides.

Generative AI represents not a rupture but a familiar pressure point in the long history of cultural reproduction. It forces societies to clarify standards, articulate values, and define what counts as meaningful creativity under conditions of abundance. Plato’s fear was not wrong, but it was incomplete. Greek culture did not stagnate under the weight of imitation. It refined its criteria for truth, depth, and excellence precisely because imitation became unavoidable. The challenge posed by AI is analogous. Meaning will not disappear because imitation has become easy. It will endure if judgment, responsibility, and interpretive discipline are cultivated alongside the tools that now make repetition effortless.

Conclusion: Repetition, Standards, and the Survival of Meaning

The history traced here suggests that repetition is not a symptom of cultural decay but a structural condition of cultural endurance. Plato’s anxiety about mimesis arose not because imitation existed, but because it had become powerful, abundant, and effective. When forms repeat easily, societies are forced to confront how meaning is preserved, how judgment is exercised, and how standards are maintained. Repetition exposes the need for discipline. It reveals that meaning does not survive on novelty alone, but on the careful governance of form, interpretation, and authority.

Plato was right to fear aesthetic abundance without standards, but wrong to imagine that imitation necessarily hollows out culture. Greek civilization did not collapse under the weight of mimesis. It adapted, diversified, and sharpened its intellectual tools. Philosophy refined its criteria for truth, drama developed greater self-awareness and complexity, and audiences became more discerning participants rather than passive recipients. Repetition did not erase judgment. It made judgment unavoidable. When imitation proliferates, cultures must articulate what distinguishes insight from noise, depth from familiarity, and truth from pleasing appearance. Standards become explicit precisely because repetition makes complacency impossible.

Seen across history, this pattern repeats with remarkable consistency. Writing, print, mass media, and now generative AI have each triggered fears that mechanical reproduction would overwhelm meaning and flatten cultural life. Each time, however, the survival of culture depended not on suppressing imitation but on strengthening interpretive institutions, ethical frameworks, and critical literacy. Meaning endured when societies invested in judgment rather than retreating into nostalgia for scarcity. The danger lay not in repetition itself, but in abandoning responsibility for how repeated forms were evaluated, authorized, and trusted in public life.

The lesson of Plato’s anxiety, then, is not rejection but orientation. Repetition will always accompany cultural growth, because imitation is inseparable from learning, memory, and transmission. The decisive question is whether standards evolve alongside it. Meaning survives not because creativity is rare, but because judgment is cultivated, taught, and defended. In a world where imitation is easy, responsibility becomes the true measure of originality. Civilization persists not by escaping repetition, but by repeatedly learning how to govern it.

Bibliography

- Alwine, Andrew T. “Freedom and Patronage in the Athenian Democracy.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 136 (2016): 1-17.

- Annas, Julia. An Introduction to Plato’s Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Aristotle. Poetics. Translated by Stephen Halliwell. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Baidoo-anu, David. “Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning.” Journal of AI 7:1 (2023): 52-62.

- Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021.

- Boys-Stones, George. Post-Hellenistic Philosophy: A Study of Its Development from the Stoics to Origen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Csapo, Eric. Actors and Icons of the Ancient Theater. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Csapo, Eric, and William J. Slater. The Context of Ancient Drama. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Fine, Gail. Plato on Knowledge and Forms. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Floridi, Luciano. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

- Goldhill, Simon. Reading Greek Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- —-. Who Needs Greek? Contests in the Cultural History of Hellenism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Gray, Vivienne. “Mimesis in Greek Historical Theory.” The American Journal of Philology 108:3 (1987): 467-486.

- Griswold, Charles L. “Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003.

- Hall, Edith. Greek Tragedy: Suffering under the Sun. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Halliwell, Stephen. The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- —-. Aristotle’s Poetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- —-. Greek Laughter: A Study of Cultural Psychology from Homer to Early Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Havelock, Eric A. Preface to Plato. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

- Moors, Kent F. “Plato’s Use of Dialogue.” The Classical World 72:2 (1978): 77-93.

- Nagy, Gregory. Homeric Questions. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996.

- Nightingale, Andrea Wilson. Genres in Dialogue: Plato and the Construct of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- —-. Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy: Theoria in Its Cultural Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Plato. Gorgias. Translated by Donald J. Zeyl. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987.

- —-. Ion. Translated by Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997.

- —-. Laws. Translated by Thomas L. Pangle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

- —-. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995.

- —-. Protagoras. Translated by Stanley Lombardo and Karen Bell. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992.

- —-. Republic. Translated by G. M. A. Grube, revised by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992.

- —-. Symposium. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989.

- Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. New York: Viking, 1985.

- Taplin, Oliver. Greek Tragedy in Action. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Williams, Raymond. Culture and Society, 1780–1950. New York: Columbia University Press, 1958.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.27.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.