Rome’s experience demonstrates that political systems can endure long after leadership has ceased to merit confidence or respect.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Authority Becomes Performance

Political systems do not collapse the moment leadership loses credibility. More often, authority persists through habit, fear, and institutional adaptation long after confidence in the ruler has eroded. Governance continues, not because leadership inspires trust, but because removing it appears more dangerous than enduring it. In such conditions, power does not simply fail. It changes character. Authority becomes performative, relying on spectacle, ritual, and symbolic excess to compensate for the loss of coherence, restraint, and administrative competence.

Imperial Rome offers the clearest early example of this transformation. The principate was designed to stabilize the Roman world after civil war by concentrating power while preserving republican appearances. As long as imperial conduct aligned with expectations of dignity, moderation, and effective administration, this system functioned tolerably well. Problems arose not when emperors became autocratic, but when credibility itself collapsed. Erratic behavior, public humiliation of elites, and symbolic extravagance strained the fiction that the emperor governed in the interests of order. Yet even then, the system did not immediately correct itself. Authority remained intact, increasingly detached from respect.

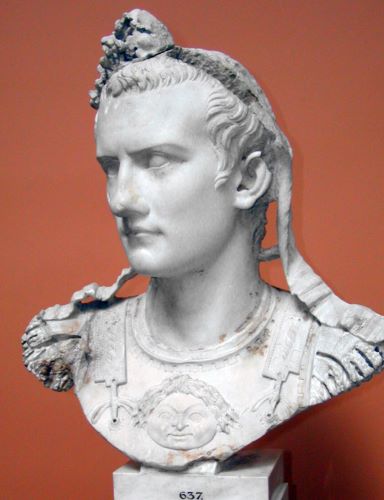

Figures such as Caligula and Commodus illustrate this moment of detachment with unsettling clarity. Their reigns were marked by grandiosity, unpredictability, and theatrical self-presentation that undermined imperial dignity. Senators, generals, and administrators recognized the danger, but removal was repeatedly deferred. The memory of civil war loomed larger than the absurdity of leadership. As a result, elites adapted. They learned to govern around the emperor, to normalize instability, and to treat spectacle as survivable so long as institutions could continue functioning beneath it.

What follows argues that Rome demonstrates how authority can survive long after credibility collapses, precisely because institutions fear the consequences of intervention. Spectacle becomes a substitute for legitimacy. Excess becomes tolerable. Absurdity becomes routine. Authority endures not because it commands respect, but because it organizes behavior and delays chaos. Understanding this dynamic requires shifting attention away from individual pathology and toward institutional tolerance. Rome did not fall because emperors became ridiculous. It endured because elites learned to live with dysfunction until the performance of authority could no longer contain its own contradictions.

The Princeps and the Illusion of Republican Continuity

The principate emerged from a political trauma that made overt monarchy unacceptable. Augustus did not abolish the Republic. He preserved its language, offices, and rituals while quietly hollowing out their independence. The title princeps signaled first among equals, not king, and this distinction mattered deeply to Roman political culture. Authority was framed as stewardship rather than domination, continuity rather than rupture. The illusion of republican governance was not a cosmetic choice. It was the foundational mechanism through which imperial power became tolerable after decades of civil war.

This system depended on a delicate alignment between performance and capacity that could not be easily replicated. Augustus exercised restraint, respected senatorial forms, and governed through an expanding but largely functional administrative apparatus. His authority appeared legitimate not merely because it was legally sanctioned, but because it delivered order, security, and predictability after prolonged instability. Republican institutions continued to operate in recognizable form, even as their autonomy narrowed. The Senate debated, magistrates served, and law retained its familiar rhythms. The illusion worked because it was reinforced by outcomes. Performance did not yet substitute for governance. It accompanied it, lending credibility to a system that still functioned effectively beneath its theatrical restraint.

The fragility of this arrangement lay in its reliance on personal conduct rather than institutional constraint. The principate lacked formal mechanisms for disciplining the emperor without destabilizing the entire political order. Authority rested on expectation, not enforceable limits. As long as emperors observed decorum, restraint, and respect for republican sensibilities, the fiction of shared governance held. When they did not, there was no constitutional remedy that did not risk reopening the wounds of civil war. Republican continuity thus became less a system of checks and balances than a shared elite pretense, sustained by cooperation, silence, and calculated tolerance rather than by law.

Over time, administrative complexity increased while republican oversight diminished. Provincial governance, military command, and fiscal management concentrated around the imperial household and its appointees. Senators retained status but lost leverage. Their participation affirmed legitimacy without shaping outcomes. The illusion of continuity persisted, but its content thinned. Republican forms increasingly functioned as ritual affirmations of order rather than instruments of control. Authority remained recognizable even as its sources shifted decisively away from collective governance.

The principate therefore institutionalized a dangerous tradeoff that would only become visible over time. By preserving republican appearances, it stabilized Rome in the short term and forestalled renewed civil conflict. Yet it also delayed the development of mechanisms capable of correcting imperial dysfunction once restraint eroded. When later emperors violated expectations of dignity and moderation, elites were left with an impossible choice: confront the emperor and risk systemic collapse or tolerate excess and preserve continuity. The illusion of republican continuity, once Rome’s great political innovation, became the very structure that allowed authority to persist after credibility began to erode, transforming performance into a substitute for legitimacy.

Administrative Drift and the Hollowing of Imperial Governance

Imperial governance did not unravel through sudden incompetence or collapse at the center. Instead, it thinned gradually as the scale and complexity of the Roman world outpaced the administrative tools available to manage it. Expansion brought wealth, manpower, and prestige, but it also imposed burdens of coordination that exceeded the capacity of existing institutions. Communication delays, regional variation, and the sheer size of the empire ensured that imperial directives were interpreted, adapted, or ignored long before they were uniformly enforced. Authority remained centralized in theory, but governance became increasingly dispersed in practice. What mattered most was not whether orders were followed precisely, but whether disorder remained contained. This tolerance for variance marked a quiet recalibration of what imperial control meant, allowing the system to function while masking the erosion of coherence beneath its surface.

This drift was most visible in the provinces, where governors, military commanders, and local elites exercised wide discretion. Imperial oversight existed, but it was episodic and reactive rather than continuous. Emperors could intervene decisively in moments of crisis, yet routine administration depended on delegation and trust. This delegation hardened into autonomy. Provincial officials learned that distance insulated them from immediate correction, while the center learned to tolerate inconsistency so long as order was not visibly disrupted. Administrative drift thus became normalized, absorbed into the functioning of empire rather than treated as a threat to it.

The military further complicated this hollowing process. Legions swore loyalty to the emperor, but their daily realities were shaped by commanders, supply chains, and regional priorities. Emperors relied on military force to project authority, yet that reliance reduced their ability to discipline it. Commanders became indispensable intermediaries, translating imperial will into action while simultaneously buffering the emperor from the practical consequences of governance. As long as armies were paid and frontiers held, deviations from central control were tolerated. Capacity eroded quietly beneath the surface of continued imperial command.

The Senate’s role diminished in parallel, and its transformation illustrates how institutional continuity could coexist with declining authority. Once a central governing body, the Senate increasingly functioned as a ceremonial institution whose approval affirmed legitimacy without constraining policy. Senators still governed provinces and commanded armies, but always at the emperor’s discretion, their power personal rather than collective. Debate survived, but it no longer directed outcomes. The Senate’s survival depended on accommodation, ritual participation, and symbolic deference, reinforcing the illusion that republican governance persisted even as meaningful deliberation faded. Administrative hollowing was thus concealed by the preservation of familiar forms, allowing authority to appear stable while its foundations shifted.

What emerged was an empire governed less by coordinated administration than by negotiated equilibrium. Authority remained concentrated in the figure of the emperor, but capacity diffused across networks of officials, commanders, and local elites whose cooperation could not be compelled uniformly. Governance worked not because it was coherent, but because it was adaptable and forgiving of inconsistency. This adaptability delayed crisis by allowing the system to function without confronting its own fragmentation directly. Imperial governance survived by lowering its expectations of control while maintaining the language and symbols of centralized authority. The hollowing of administration did not weaken authority immediately. It made authority more dependent on performance, tolerance, and elite cooperation, setting the conditions under which spectacle could eventually substitute for governance.

Caligula: Absurdity as Political Reality

The reign of Caligula marks the moment when the widening gap between imperial authority and political credibility became publicly visible, yet still failed to provoke immediate structural correction. His rule did not introduce dysfunction into an otherwise healthy system. It exposed vulnerabilities that had already been normalized through administrative drift and elite accommodation. Caligula’s behavior shattered expectations that emperors would exercise restraint, respect senatorial dignity, or govern within recognizable bounds of rationality. Public humiliations, arbitrary violence, theatrical cruelty, and symbolic excess were not merely tyrannical acts. They dissolved the shared grammar of rule that had sustained the principate’s legitimacy. Authority remained absolute, but intelligibility vanished. Governance could no longer be explained as stewardship masked by republican form. Power persisted, stripped of its justificatory language.

Despite widespread recognition of instability, Rome did not respond with swift or coordinated resistance. Senators complied, courtiers adjusted, and administrators continued their work within shrinking margins of predictability. This endurance did not reflect approval or loyalty. It reflected calculation. The memory of civil war loomed larger than the daily humiliations of governance under an erratic ruler. Removing an emperor was not a corrective measure. It was a gamble with potentially catastrophic consequences. Absurdity at the top was tolerated because it appeared survivable, whereas intervention threatened systemic rupture. Elite behavior during Caligula’s reign demonstrates how political systems normalize dysfunction when the perceived cost of action exceeds the cost of endurance.

Caligula’s excesses also reveal how spectacle can replace credibility without immediately dismantling authority. His self-presentation as a god, his manipulation of ritual, and his deliberate inversion of elite norms were not random acts of madness alone. They functioned as assertions of power detached from governance. By humiliating traditional institutions, Caligula exposed their impotence. Yet those same institutions continued to operate, adapting their expectations downward. Administration did not cease. It recalibrated around the emperor’s volatility, insulating routine governance from imperial unpredictability where possible.

The significance of Caligula’s reign lies less in its brevity than in what it demonstrated. Rome could survive an emperor who violated every expectation of dignity and restraint because the system had already learned to function without meaningful imperial participation. Authority endured as position rather than performance. Absurdity became survivable, at least temporarily, because elites chose endurance over confrontation. Caligula did not invent spectacle as power. He revealed how far the Roman political system had already traveled toward tolerating it.

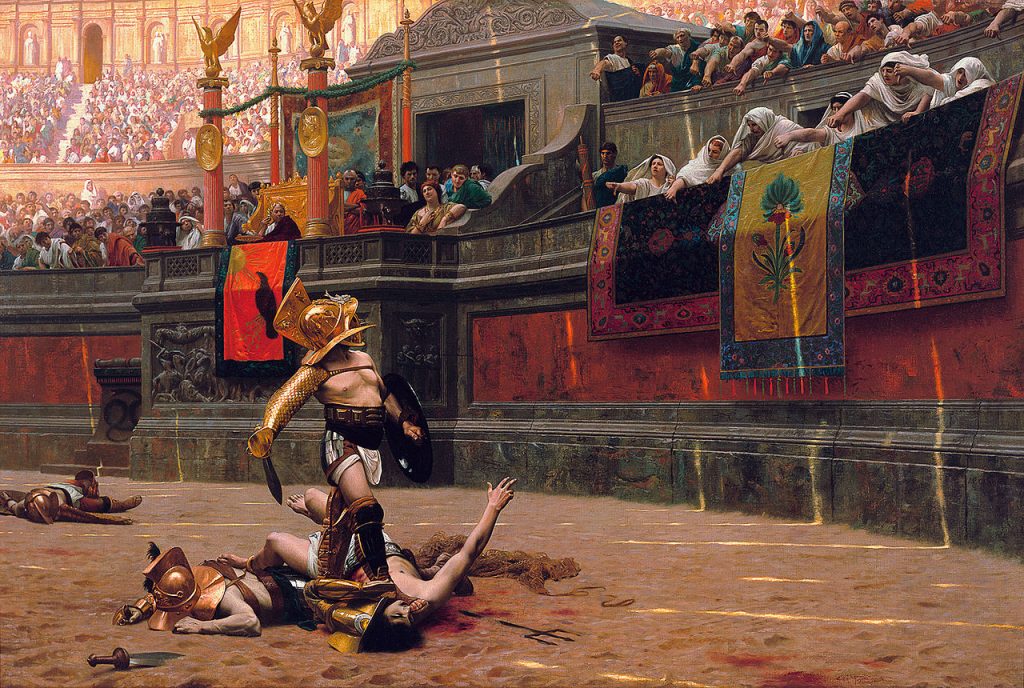

Commodus and the Normalization of Spectacle

If Caligula revealed how absurdity could coexist with authority, Commodus demonstrated how spectacle could become routine. By the late second century CE, the principate no longer depended on the personal restraint of the emperor to preserve legitimacy. Administrative drift, elite accommodation, and institutional insulation had progressed far enough that governance could continue despite prolonged dysfunction at the apex. Commodus inherited a system already accustomed to tolerating instability. His reign did not shock Rome into crisis so much as confirm how far expectations had declined.

Commodus embraced performance as the central mode of rule. His obsession with gladiatorial combat, public self-deification, and mythic self-fashioning did not merely undermine imperial dignity. It displaced governance altogether. The emperor appeared constantly, but acted rarely as an administrator. Authority was expressed through spectacle rather than judgment, visibility rather than decision. Yet the empire continued to function. Bureaucrats governed, generals managed frontiers, and fiscal systems operated with limited imperial involvement. Rome was governed around the emperor rather than through him.

Elite response to Commodus illustrates how dysfunction becomes normalized once endurance replaces correction as the dominant political strategy. Senators, court officials, and military commanders adapted by narrowing their expectations further, abandoning any remaining hope for rational or restrained leadership. What mattered was not competence, but containment. As long as Commodus did not interfere too destructively with administration, provoke military revolt, or destabilize elite alliances beyond repair, his excesses were tolerated. Rituals continued, decrees were issued in his name, and institutions performed obedience while quietly insulating daily governance from imperial interference. Spectacle became survivable precisely because it was predictable. Absurdity lost its capacity to shock and instead became an administrative variable to be managed, anticipated, and worked around.

The assassination of Commodus reveals the outer boundary of this tolerance. Spectacle could replace credibility only as long as it did not threaten the fragile equilibrium among elites, the military, and the court. When Commodus’ behavior began to endanger succession, personal security, and factional balance, endurance gave way to intervention. His removal did not represent a moral reckoning or a sudden rediscovery of republican virtue. It was a delayed institutional correction, undertaken only after normalization ceased to function. Commodus’ reign marks the moment when spectacle became fully embedded in imperial authority and also exposed its limits. Authority could survive without governance, but only until spectacle itself began to destabilize the structures that had learned to tolerate it.

Why Rome Tolerated Dysfunction

Rome tolerated imperial dysfunction not because it failed to recognize it, but because the alternatives appeared more dangerous. The Roman political imagination was shaped by the memory of civil war, proscriptions, and constitutional collapse. Stability, even degraded stability, was preferable to renewed uncertainty. By the first and second centuries CE, the principate had become synonymous with order itself. Removing an emperor was not perceived as correcting a mistake. It was perceived as reopening history’s most traumatic chapter.

Elite behavior reflected this calculation. Senators, equestrians, and military commanders understood that the emperor’s removal would require coordination, legitimacy, and force, none of which could be guaranteed without triggering wider conflict. Dysfunction at the top was survivable so long as it remained personal rather than systemic. Absurdity could be endured. Open fracture could not. Tolerance, therefore, was not passivity. It was risk management under constrained choices.

Institutional design reinforced this tolerance in ways that made correction structurally difficult even when consensus against an emperor existed. The principate deliberately avoided formal mechanisms for impeachment, deposition, or legal restraint. Power flowed through personal authority, patronage, and loyalty rather than constitutional process. This ambiguity made intervention inherently illegible. Who had the right to act? In whose name could action be justified? Against what standard of legality or legitimacy? In the absence of clear procedures, any attempt at removal appeared indistinguishable from rebellion. Inaction became the default not because elites approved of dysfunction, but because action carried existential political risk.

The administrative structure of empire further encouraged endurance. Provincial governance, fiscal administration, and military command could continue functioning despite imperial distraction or incompetence. Rome was not governed solely from the palace. It was governed through layers of delegation that insulated daily operations from the emperor’s behavior. As long as frontiers held, taxes were collected, and elites retained status, dysfunction at the center could be absorbed rather than confronted.

Social expectations also played a role, shaping how dysfunction was interpreted rather than whether it was noticed. Roman political culture prized endurance, adaptability, and loyalty to order over abstract ideals of competence or moral virtue. The emperor was not expected to govern personally in every domain. He was expected to remain emperor. Once expectations adjusted to spectacle and volatility, absurdity ceased to provoke outrage and instead became background noise. Political dysfunction was normalized because it did not immediately disrupt daily life for most elites, and because acknowledgment of its significance would have demanded action few were willing to take.

Rome tolerated dysfunction because its institutions, historical memory, and elite incentives aligned to make tolerance the least dangerous option. Authority survived not because it commanded respect, but because removing it threatened systemic collapse. This endurance was not infinite, but its limits were high. Tolerance ended only when dysfunction began to destabilize succession, security, or elite equilibrium itself. Until that point, endurance remained the most conservative political choice available, even as it allowed credibility to erode steadily at the heart of empire.

Authority without Credibility as a Repeating Pattern

Rome’s experience reveals that authority does not require credibility in order to persist. Once a political system learns to function around leadership rather than through it, legitimacy becomes detached from performance. Offices continue to command obedience even when those who occupy them no longer inspire confidence or respect. The Roman principate demonstrates how authority can survive on recognition alone, sustained by habit, fear of alternatives, and institutional inertia. What collapses first is not power, but the expectation that power must make sense.

This pattern recurs because political systems prioritize continuity over correction, even when dysfunction is widely acknowledged. Removing a leader whose credibility has collapsed threatens the stability of the entire structure that leader anchors. Institutions therefore adapt by lowering expectations, redistributing responsibility, and insulating routine governance from the apex of authority. In Rome, this meant administrators, generals, and provincial elites quietly managing affairs while emperors performed sovereignty through ritual, proclamation, and spectacle. Authority remained visible and intact even as its functional center hollowed out. Credibility became optional so long as order appeared to persist and elites retained their positions, resources, and relative security.

A key feature of this pattern is the normalization of absurdity. Once elites accept that leadership will not behave rationally or competently, dysfunction becomes predictable rather than shocking. Predictability reduces urgency. Absurd acts are absorbed into routine calculations rather than treated as emergencies. In Rome, theatrical excess, public humiliation of elites, and symbolic inversion ceased to provoke resistance once they were understood as permanent features rather than temporary deviations. Authority endured because expectations adjusted downward, not because behavior improved.

The repetition of this pattern across history reflects a structural truth about power that extends well beyond Rome. Authority organizes behavior even when it no longer persuades or commands respect. People comply not because they believe, but because coordination requires a focal point and alternatives appear fragmented or dangerous. Institutions continue to operate because they are designed to preserve continuity, not to adjudicate legitimacy. From imperial courts to modern bureaucracies, systems learn to protect authority as a stabilizing fiction. Credibility can be sacrificed without immediate collapse. Coherence cannot. The longer this adaptation succeeds, the more deeply illusion becomes embedded as a governing principle rather than a temporary accommodation.

Authority without credibility survives until it begins to undermine the very stability it once preserved. When dysfunction disrupts succession, security, or elite cooperation, tolerance collapses. What follows often appears sudden, but it is the delayed result of long accommodation and managed decline. Rome’s lesson is not that spectacle destroys power immediately. It is that power can survive spectacle for an unsettling length of time, and that this endurance itself accelerates decay. Authority that no longer requires credibility hollows institutions from within, leaving them fragile long before collapse becomes visible.

The Breaking Point: When Spectacle Fails

Spectacle stabilizes authority only as long as it continues to organize elite behavior and preserve basic coordination across institutions. In Rome, spectacle functioned as a substitute for credibility by creating predictability where legitimacy had eroded. Ritualized excess, symbolic domination, and theatrical authority reassured elites that the system, however degraded, remained intelligible. Yet this substitution carried inherent limits. Performance could mask decay, but it could not repair succession uncertainty, fiscal strain, or elite insecurity indefinitely. When spectacle ceased to reassure and instead amplified anxiety, its political value collapsed. At that moment, illusion no longer delayed crisis. It accelerated it.

The Roman record shows that breakdown rarely occurred because rulers were absurd. It occurred when absurdity disrupted predictability. Caligula and Commodus were tolerated not because they were respected, but because their behavior could be absorbed into existing patterns of adaptation. Once spectacle became destabilizing rather than containable, elite tolerance evaporated. What had once been survivable became dangerous. Spectacle failed not morally, but strategically. It no longer delayed chaos. It produced it.

At this point, correction appeared unavoidable, even at the cost of violence and instability. Assassination, palace coups, and rapid regime turnover were not signs of sudden political awakening or renewed civic virtue. They were delayed responses to long-managed dysfunction. Rome did not intervene early because intervention threatened systemic collapse. It intervened late because collapse became unavoidable without action. The breaking point was reached when endurance ceased to preserve order and instead undermined elite security, succession planning, and military loyalty. Authority without credibility could survive absurdity for years. It could not survive unpredictability that threatened the governing class itself.

The failure of spectacle reveals the paradox at the heart of hollow authority. The strategies that preserve power during decline also deepen the conditions for collapse. By postponing correction, institutions allow contradictions to accumulate until they can no longer be absorbed. When spectacle fails, it does so abruptly, exposing fragility long concealed by performance. Rome’s experience demonstrates that authority can outlive credibility, but not indefinitely. The longer spectacle substitutes for governance, the more severe the reckoning when performance finally ceases to function.

Conclusion: The Long Shadow of Roman Spectacle

Rome’s experience demonstrates that political systems can endure long after leadership has ceased to merit confidence or respect. Authority survived not because emperors governed well, but because institutions, elites, and populations adapted to dysfunction rather than confronting it directly. Spectacle, ritual, and symbolic excess did not merely distract from decline. They became governing tools that allowed power to persist without credibility. What mattered was not whether authority made sense, but whether it continued to organize behavior and delay chaos.

The Roman case reveals that spectacle is most effective when institutions are strong enough to absorb its costs. Bureaucracy, military command, provincial administration, and elite networks insulated daily governance from imperial volatility. This insulation allowed absurdity at the top to coexist with relative stability below. Yet the same insulation also removed incentives for correction. As long as governance could proceed around the emperor, spectacle remained tolerable. Authority endured because intervention appeared riskier than accommodation, even as credibility steadily eroded.

The long shadow of Roman spectacle lies in how it reframes political failure across time. Collapse was not caused by excess alone, nor by elite blindness or moral decay. It was produced by rational calculation under constrained options. Elites tolerated dysfunction because the alternatives promised fragmentation, violence, and uncontrollable succession struggles. Spectacle delayed reckoning by preserving continuity, but at the cost of deepening structural weakness beneath the surface. Each act of endurance transferred risk forward, allowing contradictions to accumulate rather than resolve. By the time correction became unavoidable, it arrived violently and without institutional repair. Rome did not fall because it failed to recognize absurdity. It fell because it learned how to live with it, normalize it, and build around it too effectively.

The lesson of Roman spectacle is therefore not confined to antiquity or imperial politics. Authority can survive without credibility wherever institutions prioritize continuity over correction and where performance substitutes for governance. Such systems appear stable precisely because they suppress moments of decision. Spectacle preserves power in the short term while hollowing it in the long term, replacing accountability with endurance and legitimacy with habit. Rome’s longevity under absurd emperors was not evidence of resilience. It was evidence of delayed reckoning. Power that no longer requires legitimacy can persist for generations, but when it finally collapses, it leaves little behind that can be easily repaired, trusted, or rebuilt.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Barrett, Anthony A. Caligula: The Abuse of Power. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914–1927.

- Geertz, Clifford. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Complete Roman Army. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003.

- Hammer, Dean. “Roman Spectacle Entertainments and the Technology of Reality.” Arethusa 43:1 (2010: 63-86.

- Hekster, Olivier. Commodus: An Emperor at the Crossroads. Amsterdam: J. C. Gieben, 2002.

- Herodian. History of the Roman Empire. Translated by C. R. Whittaker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969–1970.

- Lintott, Andrew. The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC–AD 337). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Morey, W. C. “How Rome Governed the Provinces.” The Biblical World 2:1 (1893): 29-37.

- North, Douglass C., John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Potter, David S. The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Price, S. R. F. “Between Man and God: Sacrifice in the Roman Imperial Cult.” The Journal of Roman Studies 70 (1980): 28-43.

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. London: Penguin Classics, 2007.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Winterling, Aloys. Caligula: A Biography. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.29.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.