The history of classical Athens reveals a form of political power that is easy to overlook precisely because it operates through absence rather than confrontation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power, Participation, and the Politics of Absence

Political power in classical Athens did not reside solely in laws, offices, or coercive force. It depended on participation that was visible, routine, and publicly reaffirmed through everyday civic life. To be a citizen was not simply to possess legal status, but to appear, to transact, to vote, to worship, and to be seen doing so. Markets, assemblies, and festivals were not peripheral to democracy. They were its infrastructure. Authority drew strength from the constant performance of consent, enacted through presence rather than declared through ideology.

This embeddedness of politics in daily life produced a distinctive vulnerability. Because legitimacy relied on participation, absence carried meaning. When citizens withdrew from markets, avoided festivals, or disengaged from civic rituals, they did more than opt out of social life. They signaled a fracture in the relationship between authority and consent. Such withdrawal was neither apathy nor rebellion. It was a form of political communication that operated without violence, lawbreaking, or formal opposition. In a system where power was sustained by visible normalcy, the refusal to appear undermined that normalcy at its core.

Modern political language often treats non-participation as weakness, resignation, or disengagement. Classical Athens suggests a different interpretation. Withdrawal functioned as a constitutional signal precisely because it denied the polis what it required most: the appearance of collective affirmation. When citizens did not show up, did not trade, did not celebrate, and did not perform unity, authority lost its everyday confirmation. This loss was destabilizing not because it halted governance immediately, but because it revealed how thoroughly power depended on voluntary repetition. Participation was not enforced at every moment. It was assumed. Withdrawal disrupted that assumption and forced the question of whether authority could persist without continuous, visible consent expressed through ordinary life.

What follows argues that civic withdrawal in fifth-century Athens operated as a subtle but potent form of political power. By walking away from the rituals and markets that sustained democratic and imperial authority, citizens punctured the illusion of cohesion on which that authority depended. The absence of crowds, transactions, and ritual affirmation transformed silence into a political condition rather than a personal choice. The Athenian case reveals a broader political truth: systems of power that depend on participation are uniquely vulnerable to its absence. Understanding this dynamic in antiquity clarifies why withdrawal remains threatening to modern regimes that rely on the appearance of normality to sustain control. Power endures not simply because it commands, but because people continue to show up, and it falters when they collectively decide not to.

Participation as a Democratic Obligation in Classical Athens

In classical Athens, participation was not an optional expression of civic enthusiasm but a defining feature of citizenship itself. Political identity was enacted through presence in shared spaces rather than mediated through representation or abstraction. To be a citizen was to appear in the assembly, to serve on juries, to trade in the agora, and to take part in festivals that bound the polis together. Participation was both a right and a responsibility, embedded in law, custom, and expectation. Absence from civic life carried moral and political weight, signaling disengagement from the collective project of self-rule.

The institutional design of Athenian democracy reinforced this obligation in systematic and deliberate ways. The ekklesia depended on physical attendance to function, and large juries drawn by lot required citizens to give time, labor, and judgment to the administration of justice. Payment for jury service and assembly attendance was not merely pragmatic compensation but an ideological signal that participation was a civic duty worthy of public support. These mechanisms ensured that political engagement was not monopolized by wealth or leisure. They normalized participation as a routine practice, integrating political action into the rhythms of work, family life, and economic survival. In doing so, they blurred the boundary between private life and public responsibility.

Social norms further amplified this expectation. Public discourse in Athens treated civic engagement as a marker of virtue and masculinity, while withdrawal invited suspicion. The term idiōtēs, from which the modern word “idiot” derives, originally described a private person who did not take part in public affairs. This linguistic distinction reveals how deeply participation was tied to social esteem. To remain outside the civic sphere was to risk marginalization, not because the state coerced attendance at every moment, but because the community understood absence as a failure of civic responsibility.

Markets and economic life were no less political in this regard. The agora functioned simultaneously as a commercial center and a space of political visibility. Trading, meeting, and observing public business were intertwined activities rather than separate spheres. Economic participation reinforced civic belonging by making citizens visible to one another and to magistrates, officials, and peers. Wealth, reputation, and influence circulated through these shared spaces, binding material exchange to political standing. Refusing to appear in the market disrupted not only commerce but recognition itself, signaling withdrawal from the everyday performance of membership in the polis.

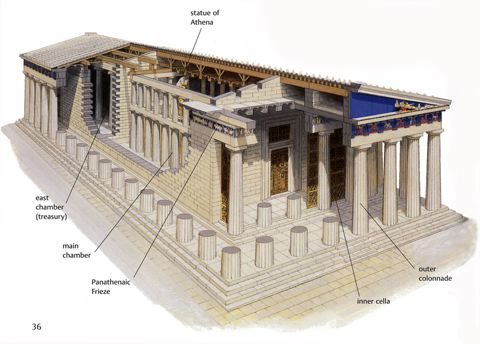

Religious festivals and civic rituals extended this logic beyond formal politics. Panathenaic processions, dramatic competitions, and sacrificial rites were not merely cultural events. They were performances of unity that reaffirmed shared values, collective memory, and civic hierarchy. Attendance was both expected and conspicuous. Festivals drew citizens into synchronized acts of celebration and remembrance, reinforcing the sense that the polis was cohesive, orderly, and legitimate. Absence stood out precisely because participation was assumed. Refusal or withdrawal disrupted the choreography of consensus, introducing visible dissonance into what was meant to appear seamless.

These practices reveal why participation in Athens functioned as a democratic obligation rather than a discretionary choice. Politics permeated social, economic, and religious life so thoroughly that withdrawal was immediately legible as deviation. Authority depended less on force than on the habitual presence of citizens performing their roles in public view. This dependence created strength through cohesion, but it also created vulnerability. Because participation was assumed rather than compelled at every moment, its absence carried communicative power. Understanding participation as obligation clarifies why withdrawal could operate as a political act capable of unsettling authority without direct confrontation.

Markets, Festivals, and the Performance of Consent

In classical Athens, consent was not expressed primarily through abstract affirmation or periodic elections. It was enacted daily through participation in shared spaces where political, economic, and social life converged. Markets and festivals served as stages on which the legitimacy of the polis was continuously performed rather than merely asserted. The appearance of bustling trade, crowded processions, and collective celebration communicated stability, cohesion, and popular assent to both citizens and observers. Authority relied on these visible signs of participation to sustain itself as normal, accepted, and enduring. Without this constant display of engagement, democratic rule risked appearing fragile, contingent, and subject to challenge.

The agora was the most important of these stages. It functioned simultaneously as a marketplace, meeting ground, and political arena. Citizens did not merely buy and sell goods there. They observed magistrates, overheard debates, encountered legal proceedings, and witnessed the routines of governance unfolding in public view. Economic activity and political visibility were inseparable. To appear in the agora was to place oneself within the shared life of the polis, affirming membership through presence. Regular participation reinforced the impression that civic order was intact and broadly supported.

Markets also generated prestige and revenue, both of which were essential to Athenian authority. Commercial vitality signaled prosperity to allies and rivals alike, while taxation, fees, and imperial tribute circulated through these spaces. A thriving agora suggested effective governance and justified Athens’ claims to leadership by presenting the city as a hub of wealth, order, and opportunity. When citizens participated in market life, they did more than pursue private gain. They helped stage a public spectacle of abundance and legitimacy that underwrote political power. Economic withdrawal struck at both material foundations and symbolic credibility, weakening authority by disrupting the appearance of success and consent.

Festivals extended this performance of consent into the religious and cultural realm. Events such as the Panathenaia or the Dionysia drew large crowds into ritualized displays of unity, hierarchy, and shared memory. Processions, sacrifices, and dramatic competitions presented Athens to itself as a harmonious collective bound by gods, ancestors, and civic pride. Participation was expected and conspicuous, with absence easily noticed against the density of bodies and ritual movement. Attendance affirmed belonging, while synchronized action transformed individual citizens into a visible political whole, momentarily dissolving social divisions beneath the image of collective identity.

The political function of festivals lay not in their explicit messaging, but in their ability to render authority natural. By embedding power within celebration, ritual obscured coercion and conflict beneath joy and tradition. Citizens who marched, watched, and applauded participated in the reproduction of civic legitimacy even when they held private doubts. The spectacle of unity mattered as much as genuine agreement. Absence from such events disrupted this illusion, creating gaps in what was meant to appear seamless and universally embraced.

Markets and festivals operated as complementary mechanisms in the performance of consent. One displayed everyday normalcy through economic exchange. The other elevated that normalcy into ritual affirmation. Together, they sustained the appearance of a polis functioning with the willing participation of its citizens. When individuals or groups withdrew from these spaces, the disruption was immediately visible. Empty stalls, diminished crowds, or absent bodies spoke loudly in a system that depended on being seen. In Athens, consent was not only given. It was performed, and when the performance faltered, authority was exposed as contingent rather than inevitable.

Crisis and Withdrawal: When Citizens Refused to Participate

Periods of crisis in classical Athens strained the assumption that participation was automatic and continuous. Prolonged warfare, economic hardship, and political instability placed heavy demands on citizens whose daily lives were already deeply entwined with civic obligation. Under such conditions, withdrawal emerged not as a rejection of democracy itself, but as a response to the perceived failure of leadership or the erosion of shared purpose. When the costs of participation began to outweigh its meaning, absence became a visible form of judgment.

The Peloponnesian War provides the clearest context for this dynamic. As the conflict dragged on, the burdens of taxation, tribute management, and military service intensified, while confidence in strategic decision-making declined. Thucydides records not only battlefield losses but the moral exhaustion of the citizenry as repeated campaigns produced diminishing returns and escalating casualties. Market disruption, shortages, and population displacement altered everyday rhythms, making participation harder to sustain both materially and psychologically. In this environment, reduced attendance at assemblies, diminished engagement in public debate, and avoidance of communal obligations reflected growing disillusionment rather than indifference. Withdrawal became a way for citizens to register skepticism toward policies that demanded sacrifice without delivering security, stability, or honor in return.

Withdrawal during crisis also carried economic dimensions. Citizens who abstained from market participation or limited their engagement in commercial exchange disrupted more than supply and demand. They undermined the public performance of prosperity that imperial Athens depended upon to justify leadership and extract compliance from allies and subjects. Empty stalls, reduced trade, and slowed circulation of goods signaled instability both internally and externally, weakening Athens’ image as a thriving center of power. Such absence communicated doubt about the legitimacy of continued imperial extraction, especially when revenues no longer translated into shared civic benefit or collective confidence.

Religious and cultural disengagement further intensified the signal. Festivals that once unified the polis could appear hollow during periods of suffering and distrust. Refusal to participate in public rites, processions, or celebrations transformed silence into a collective statement. These rituals were designed to reaffirm order and divine favor, and their disruption suggested a rupture between civic authority and communal belief. In a society where gods, city, and people were symbolically intertwined, absence from ritual carried unmistakable political resonance.

Importantly, these acts of withdrawal did not constitute organized rebellion or explicit protest. They lacked leaders, slogans, or formal demands, allowing participants to avoid the risks associated with open confrontation. Their power lay in accumulation rather than coordination. Each absence was individually deniable but collectively unmistakable, producing a thinning of participation that authority could neither easily punish nor easily reverse. The polis confronted not violent opposition, but a gradual erosion of the practices that sustained legitimacy itself. In moments of crisis, Athenian citizens demonstrated that disengagement could function as a form of pressure, exposing the dependence of power on continued participation and revealing withdrawal as a quiet but destabilizing political force.

Withdrawal as Constitutional Signal, Not Disobedience

Withdrawal in classical Athens did not operate as lawbreaking or refusal of authority in the modern sense. It functioned within the assumptions of the democratic system rather than against them. Citizens who disengaged from markets, assemblies (ekklesia), or rituals did not necessarily reject the legitimacy of the polis itself. Instead, they signaled that legitimacy was under strain. Because Athenian democracy depended on participation rather than enforcement, absence communicated dissent without violating formal rules. Withdrawal spoke in the language the system understood best: visibility, or its deliberate absence.

This distinction matters because Athenian political culture drew a sharp line between rebellion and non-participation. Rebellion invited repression, legal sanction, and moral condemnation, and it justified the deployment of force in defense of order. Withdrawal did none of these things. It remained ambiguous, deniable, and dispersed across individuals rather than concentrated in organized opposition. Citizens could plausibly claim fatigue, illness, economic necessity, or private obligation. No single absence was decisive. Yet when such absences accumulated, their political meaning became unmistakable. Authority could not easily punish withdrawal without revealing its own dependence on consent. To criminalize non-participation would have exposed the fragility of democratic legitimacy, transforming voluntary civic life into compelled obedience and undermining the very ideals Athens claimed to uphold.

Withdrawal functioned as a constitutional signal rather than an act of disobedience. It communicated that the relationship between rulers and ruled was faltering without asserting an alternative order or demanding immediate institutional change. By refusing to perform consent, citizens forced authority to confront its reliance on everyday affirmation. Assemblies with thinning attendance, markets lacking vitality, and festivals missing expected crowds revealed governance as an achievement requiring continual renewal rather than a permanent condition. The signal was not “we reject the law,” but “the law no longer commands our presence.” This subtlety allowed withdrawal to erode legitimacy gradually, operating beneath the threshold that would have triggered repression while still exerting real pressure on political authority.

Understanding withdrawal in this way clarifies why it was so difficult for Athenian authorities to address. Law could punish illegal action, but it could not compel enthusiasm, trust, or belief without undermining democratic ideals. Efforts to force participation would have transformed consent into coercion, hollowing out the very legitimacy the system sought to preserve. Withdrawal thus operated as a uniquely democratic form of pressure. It revealed that constitutional order depended not only on institutions and statutes, but on the continued willingness of citizens to show up and be seen participating in them.

Authority without Violence: How Non-Participation Undermined Power

Athenian political authority relied far more on consent than on coercion, a reality that made non-participation especially destabilizing. Unlike regimes that governed through standing armies or centralized bureaucratic force, classical Athens governed through citizens who enacted power by showing up. Assemblies functioned only if bodies filled the Pnyx. Courts operated only if jurors appeared. Markets signaled stability only if trade continued. These were not symbolic details but operational necessities. When citizens withdrew from these spaces, authority did not confront armed resistance or overt defiance, but something more corrosive: the gradual erosion of the conditions that made rule possible in the first place. Power faltered not because it was challenged directly, but because it was no longer being reproduced through everyday civic action.

Non-participation undermined power precisely because it refused the drama of confrontation. Violence invites counter-violence. Open rebellion clarifies sides and legitimizes repression. Withdrawal did neither. It denied authority the spectacle of opposition while simultaneously depriving it of affirmation. Leaders could not point to insurgents to justify force, nor could they claim popular unity when civic spaces thinned. The absence of crowds, transactions, and ritual participation transformed silence into a political fact that could not be easily explained away or punished without contradiction.

This dynamic reveals an important distinction between force and power. Force can compel behavior, but power depends on recognition. Athens possessed the capacity to punish treason, suppress revolt, and prosecute disorder, yet it lacked mechanisms to compel belief or enthusiasm without betraying its democratic character. Non-participation exploited this limitation. It targeted not the instruments of enforcement, but the social fabric that rendered enforcement legitimate. Authority weakened not because it was attacked, but because it was no longer performed back to itself through citizen action.

In this sense, withdrawal represented a form of political leverage uniquely suited to a participatory system. It converted freedom into pressure by withholding what authority needed most: normalcy. Without violence, slogans, or organization, citizens demonstrated that governance rested on fragile, renewable consent rather than inevitability. Power persisted only so long as people continued to enact it through daily participation. When they stopped, authority remained formally intact but substantively hollow, still possessing offices and laws but lacking the lived affirmation that gave those structures meaning. The result was not immediate collapse, but exposure. Democratic power was revealed as contingent, dependent, and vulnerable to quiet refusal.

Walking Away from Empire: Athens and the Illusion of Stability

By the mid–fifth century BCE, Athens was not merely a democracy but an empire, and this dual identity placed intensified demands on participation. Imperial authority required more than military dominance or tribute extraction. It depended on the continuous appearance of stability, prosperity, and internal unity, both to reassure subject allies and to deter rebellion. The routines of civic life at home were inseparable from imperial legitimacy abroad. Crowded assemblies, active markets, and well-attended festivals projected an image of a polis confident in its leadership and secure in its power. Participation functioned as visible evidence that empire rested on shared consent rather than naked coercion, masking the asymmetries of power that imperial rule necessarily entailed.

Empire intensified the political stakes of withdrawal. As Athens extracted tribute from subject states and expanded its naval reach, the costs of imperial policy increasingly fell on its own citizens through taxation, conscription, and prolonged military engagement. When participation declined during periods of imperial strain, the signal extended beyond domestic dissatisfaction. It suggested that the social compact sustaining empire was weakening. Absence from civic rituals or economic exchange did not merely challenge local governance. It threatened the credibility of Athens’ claim to lead, protect, and civilize its allies.

The illusion of stability was especially fragile because it depended on spectacle rather than permanence. Imperial Athens needed to be seen as orderly, prosperous, and unified at all times. This made participation itself a strategic asset. Markets demonstrated economic vitality. Festivals displayed cultural supremacy. Civic rituals affirmed democratic harmony despite growing inequality and war fatigue. Withdrawal punctured this carefully maintained image by revealing the gap between imperial ambition and civic confidence. When citizens disengaged, they exposed the extent to which empire relied on performance rather than unassailable authority.

Importantly, walking away from imperial normalcy did not require coordinated opposition or ideological unity. The power of withdrawal lay in its ordinariness and deniability. Citizens did not need to denounce empire publicly or organize resistance networks. By simply failing to appear where affirmation was expected, they allowed instability to surface organically. Empty seats, diminished crowds, and slowed commerce carried political meaning precisely because the system assumed participation as default. Authority could suppress rebellion and prosecute dissent, but it could not easily compel enthusiasm or manufacture presence without revealing the fragility it sought to conceal. Attempts to enforce participation would have undermined the very illusion of voluntary consent that sustained imperial legitimacy.

Athens’ experience reveals a fundamental tension inherent in participatory empires. The same civic engagement that legitimized democratic rule also created a structural vulnerability when imperial demands eroded trust and confidence. Empire required constant reassurance that sacrifice was justified and success inevitable. Withdrawal signaled the opposite. By walking away from the performances that sustained imperial legitimacy, citizens demonstrated that stability was not a fixed condition but an ongoing achievement dependent on belief, participation, and shared purpose. Once participation faltered, empire remained powerful in form but weakened in substance, increasingly reliant on force rather than consent, and exposed as contingent rather than inevitable.

Modern Echoes: Withdrawal as Political Power Today

The Athenian experience clarifies a political dynamic that remains deeply relevant in the modern world: power depends not only on obedience, but on participation that renders authority normal, legitimate, and unremarkable. Contemporary political systems, including formally democratic ones, rely on citizens to engage in markets, media ecosystems, civic rituals, and institutional routines that continuously reaffirm the system’s legitimacy. Voting is only one component of this process. Everyday participation in economic life, cultural consumption, and public discourse performs consent in ways that are often more consequential than formal political acts.

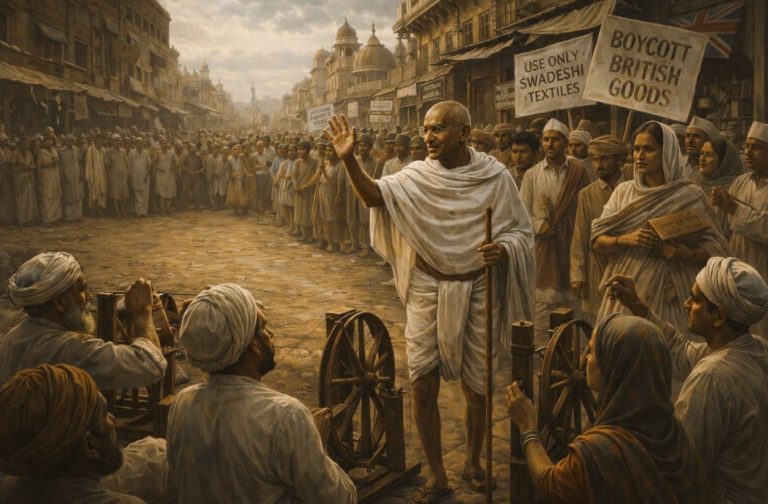

Modern withdrawal rarely takes the form of total disengagement, but it operates through selective refusal. Labor strikes, consumer boycotts, media blackouts, and mass non-cooperation disrupt the ordinary functioning of institutions without directly challenging them through violence. Like their Athenian antecedents, these acts deny authority the affirmation it requires rather than confronting it head-on. Withdrawal communicates skepticism through absence, forcing institutions to respond to a loss of legitimacy rather than an attack. Its effectiveness lies in the way it converts routine behavior into leverage. When people stop working, buying, watching, or participating, systems designed around constant engagement begin to falter, revealing how much stability depends on voluntary repetition rather than formal command.

Authoritarian and semi-authoritarian systems are particularly sensitive to withdrawal because they rely heavily on the appearance of normalcy. Elections may be managed, dissent restricted, and media controlled, but regimes still depend on citizens to show up, work, consume, and participate as if legitimacy were intact. When people disengage from these routines, the façade weakens. Empty streets, declining participation, and disrupted economic flows reveal cracks that repression alone cannot repair. As in Athens, absence becomes politically legible precisely because participation is assumed.

Even in liberal democracies, withdrawal challenges the stability of authority by disrupting the feedback loops that sustain it. Media institutions depend on audiences. Markets depend on consumers. Political legitimacy depends on visible engagement. When citizens disengage en masse, institutions face a crisis of interpretation. Are people satisfied, apathetic, or resistant? Withdrawal resists easy categorization, which makes it difficult to neutralize through conventional political responses. Its ambiguity preserves its effectiveness, allowing disengagement to function simultaneously as protest, warning, and refusal without declaring itself as any single one of these. This uncertainty forces institutions to confront the limits of their own legitimacy rather than the presence of an identifiable opponent.

The continuity between classical Athens and the modern world lies not in identical institutions, but in the shared dependence of power on participation. Withdrawal functions as a reminder that authority is not self-sustaining. It must be enacted, recognized, and reproduced through everyday behavior. When citizens walk away from the rituals that normalize power, they reveal its contingency. The Athenian case demonstrates that such refusal need not be loud to be effective. Silence, absence, and disengagement erode legitimacy gradually, often more thoroughly than protest alone, because they deny power the validation it requires to persist. Across time, withdrawal remains a quiet but enduring force capable of unsettling even the most entrenched systems of authority.

Conclusion: When Power Depends on Showing Up

The history of classical Athens reveals a form of political power that is easy to overlook precisely because it operates through absence rather than confrontation. Democratic authority depended not only on institutions, laws, or military capacity, but on the continual presence of citizens performing consent in everyday life. Markets, assemblies, festivals, and rituals were not decorative features of the polis or mere expressions of culture. They were the mechanisms through which legitimacy was made visible, reaffirmed, and normalized. Power in Athens was not simply exercised. It was enacted repeatedly through routine participation. When citizens withdrew from these spaces, they did not overthrow the system or openly defy the law. Instead, they exposed its dependence on participation that could never be fully compelled without transforming democracy into coercion.

This insight complicates modern assumptions about resistance and political change. Power is often imagined as something challenged through force, protest, or formal opposition. The Athenian case suggests that refusal can be just as consequential. Withdrawal denied authority the affirmation it required while avoiding the escalatory logic of confrontation. By not showing up, citizens communicated doubt, fatigue, or disapproval in a form that was difficult to criminalize or suppress. Absence became legible as a collective signal precisely because participation had long been assumed as the default condition of civic life.

Understanding withdrawal as political action also reframes the relationship between consent and obligation. Participation in Athens was expected, normalized, and socially enforced, yet it remained fundamentally voluntary. That tension gave democratic authority its strength, but it also produced a critical vulnerability. When participation faltered, governance continued in form but weakened in substance. Laws remained in place, offices were still occupied, and institutions persisted, but their authority grew hollow without visible affirmation. The appearance of stability could be maintained only so long as citizens continued to enact it through routine behavior. Once that enactment slowed or stopped, power was revealed as contingent, negotiated, and dependent on belief rather than inevitability.

The relevance of this dynamic extends beyond antiquity. Modern political systems, democratic and authoritarian alike, continue to depend on visible engagement to sustain legitimacy. Elections, markets, media consumption, and civic rituals all function as performances of consent. When people disengage from these practices, they expose the dependency of power on participation rather than obedience alone. Athens offers a historical reminder that authority is never self-sustaining. It endures because people show up, and it begins to unravel when they quietly decide not to.

Bibliography

- Allen, Danielle. The World of Prometheus: The Politics of Punishing in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1970.

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1998.

- —-. The Athenian Constitution. Translated by P. J. Rhodes. London: Penguin Classics, 1984.

- Cartledge, Paul. After Thermopylae: The Oath of Plataea and the End of the Graeco-Persian Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- —-. Ancient Greek Political Thought in Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- —-. Democracy: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. The Greek Imaginary: From Homer to Heraclitus. Translated by Kathleen Blamey. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982-1983.

- Eddy, Samuel K. “Some Irregular Amounts of Athenian Tribute.” The American Journal of Philology 94:1 (1973): 47-70.

- Ehrenberg, Victor. The Greek State. London: Methuen, 1960.

- Evans, Nancy. Civic Rites: Democracy and Religion in Ancient Athens. Oakland: University of California Press, 2010.

- Foucault, Michel. Society Must Be Defended. Translated by David Macey. New York: Picador, 1976.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman. The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

- Havel, Václav. The Power of the Powerless. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1979.

- Hirschman, Albert O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Lefort, Claude. Democracy and Political Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- —-. The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Osborne, Robin. Greece in the Making, 1200–479 BC. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Rhodes, P. J. A History of the Classical Greek World, 478–323 BC. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006.

- Salamanca, Emily. “Pruning of the People: Ostracism and the Transformation of the Political Space in Ancient Athens.” Philosophies 8:5 (2023).

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

- —-. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Snyder, Timothy. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Martin Hammond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Xenophon. Poroi (Ways and Means). Translated by E. C. Marchant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.03.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.