The Roman imperial cult reveals the enduring risks of defining loyalty through compelled participation rather than voluntary commitment.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Loyalty without Belief

Modern states often insist that civic unity depends upon shared participation rather than shared conviction. Loyalty, in this view, is not something citizens must inwardly feel but something they must outwardly perform. Rituals, pledges, symbols, and sanctioned narratives become the visible grammar of belonging, allowing the state to measure allegiance without probing belief. This model is especially attractive to political authorities because it appears administratively manageable. Participation can be counted, observed, and enforced, while belief remains private and inaccessible. By reducing loyalty to performative acts, the state claims to avoid ideological intrusion while quietly redefining obedience as presence. Compulsion disappears behind the language of routine, custom, and order, even as participation becomes increasingly non-optional.

The Roman Empire offers one of history’s clearest examples of this dynamic. From the first through the third centuries CE, loyalty to imperial authority was increasingly expressed through ritual acts associated with the imperial cult. These practices did not require theological assent to the emperor’s divinity. They required participation. Sacrifices, libations, oaths, and public honors functioned as civic signals, marking individuals as cooperative members of the political order. The imperial cult was not a religion of belief but a technology of visibility. Loyalty had to be seen in order to count.

This distinction between belief and participation mattered most at the point of refusal. Jews and later Christians did not reject Roman authority as such, nor did they seek political insurrection through violence. Their refusal lay in declining ritual acts they understood as religious violations, acts that compromised monotheistic commitments and covenantal boundaries. Roman officials, however, interpreted these refusals through an entirely different framework. Non-participation was read as stubbornness, social disruption, or contempt for civic norms. The refusal to perform loyalty rituals rendered dissent legible as defiance, not conscience. In this translation, the state effectively collapsed moral objection into political threat, treating principled abstention as evidence of unreliability. What appeared to dissenters as fidelity appeared to authorities as dangerous noncompliance.

The Roman experience reveals a recurring danger in state efforts to manufacture unity. When ritual participation is treated as politically neutral and dissent as a civic threat, loyalty becomes brittle rather than secure. The empire learned, slowly and unevenly, that coerced ritual does not dissolve difference but sharpens it. This lesson remains urgently relevant. When modern states reclassify religious narratives as civic heritage and incorporate them into public institutions, dissent is once again recoded as disloyalty. The problem is not belief. It is the demand to perform belonging on terms set by power.

The Imperial Cult as Political Technology

The imperial cult emerged not as a spontaneous expression of religious devotion but as a flexible political instrument adapted to the administrative needs of empire. As Roman rule expanded beyond Italy, governing elites faced the challenge of sustaining allegiance across vast cultural, linguistic, and religious differences. Rather than imposing a single theology, Roman authorities developed a system that translated loyalty into ritualized public action. Honoring the emperor through sacrifice, festivals, statues, and oaths offered a standardized way to signal acceptance of Roman rule without demanding ideological uniformity. The cult functioned as a shared civic language, intelligible across provincial boundaries.

Crucially, the imperial cult did not ask subjects to believe that the emperor was a god in any metaphysical sense. Roman religion itself was not structured around inner conviction but around correct performance. What mattered was not belief but orthopraxy, the fulfillment of visible, prescribed acts. Participation demonstrated respect for Roman authority and acknowledgment of the emperor’s role as guarantor of order, peace, and prosperity. This distinction allowed Roman officials to treat religious ritual as administratively neutral, even as it carried clear political meaning. Local populations could incorporate imperial rites alongside existing religious practices, creating a layered system in which political loyalty was expressed without formally erasing local traditions. Yet this accommodation was asymmetrical. While Rome tolerated diverse beliefs, it demanded uniform performance, privileging the appearance of unity over the reality of pluralism.

The technological power of the imperial cult lay in its visibility. Rituals were public, repetitive, and embedded in the rhythms of civic life. Festivals, processions, sacrifices, and dedications ensured that loyalty was not merely assumed but constantly reenacted. Participation became a form of social proof. Those who complied reaffirmed their place within the civic body, while those who abstained marked themselves as anomalous. The cult transformed loyalty into something that could be monitored without surveillance in the modern sense. The community itself became the instrument of observation.

This system also allowed Roman authorities to claim a posture of tolerance. Because the cult focused on action rather than belief, officials could plausibly argue that no one was being asked to abandon their gods or convictions. The requirement was framed as minimal and reasonable, a civic courtesy rather than a religious imposition. In official rhetoric, participation signaled respect for the political order, not submission to a creed. In practice, however, this framing obscured the coercive nature of compulsory participation. By defining loyalty as ritual compliance, the state quietly shifted the boundary between public duty and private conscience. Refusal was stripped of moral complexity and recast as social deviance, leaving little conceptual space for principled dissent within the civic order.

The imperial cult revealed the limits of performative loyalty as a political strategy. While it succeeded in producing outward conformity, it did not reliably generate genuine attachment among those who experienced the rituals as imposed rather than meaningful. The system functioned most smoothly where participation aligned with local incentives, elite ambition, and existing hierarchies. Where ritual obligations collided with deeply held moral or religious commitments, however, the cult exposed a fault line between obedience and allegiance. Compliance secured temporary stability, but it also hardened identities among dissenters and encouraged the state to respond with escalating pressure. As a political technology, the imperial cult proved efficient but fragile, capable of producing order while simultaneously undermining the trust and consent that sustain durable loyalty.

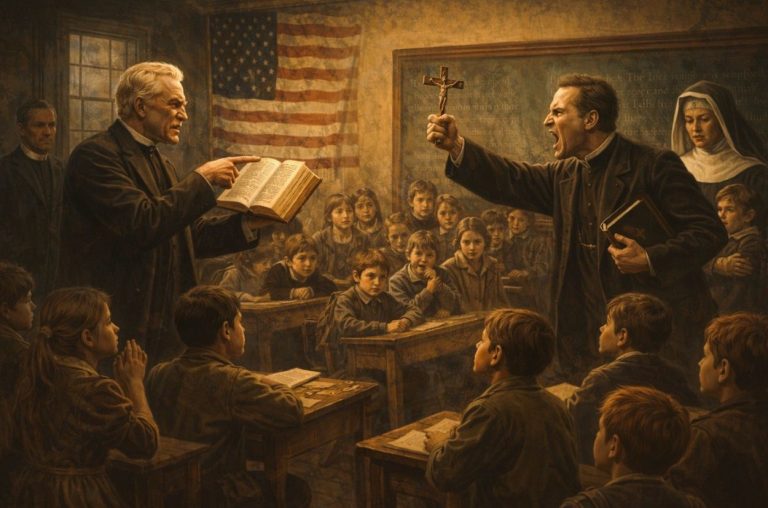

Education, Civic Space, and Ritual Normalization

The success of the imperial cult depended not only on formal decrees but on its saturation of everyday civic life. Loyalty rituals were most effective when they appeared ordinary rather than exceptional, woven into the spaces where social identity was formed and reinforced. Schools, forums, theaters, and municipal buildings became sites where imperial presence was normalized through repeated symbolic acts. In these environments, participation in loyalty rituals was less a moment of decision than a background expectation, encountered as part of learning how to belong.

Education played a central role in this process. Roman schooling did not function primarily as ideological persuasion but as habituation into civic norms. Young people encountered imperial authority through calendars structured around festivals, public holidays dedicated to the emperor, and ceremonial observances embedded in communal instruction. The repetition of these practices trained students to associate civic competence with ritual participation. Loyalty was learned not as a belief to be argued for, but as a behavior to be performed correctly and without hesitation.

Civic space amplified this pedagogical function by embedding imperial symbolism into the physical experience of daily life. Public architecture visually reinforced authority through statues, inscriptions, altars, and dedicatory monuments placed in spaces of commerce, governance, and leisure. Moving through the city meant repeatedly encountering the emperor’s symbolic presence, not as a distant abstraction but as an omnipresent civic reference point. Ritual acts performed in these spaces were not isolated religious moments but collective affirmations staged before neighbors, peers, and local elites. Participation carried social meaning beyond the ritual itself. It signaled reliability, respectability, and readiness to inhabit civic roles, while absence or refusal became immediately legible against the choreography of collective compliance.

This spatial and educational saturation reduced the visibility of coercion. Because rituals were frequent and widely shared, they appeared customary rather than imposed. The state did not need to issue constant commands; the environment itself instructed citizens on what was expected. The distinction between voluntary participation and enforced obligation blurred. Ritual compliance came to feel like common sense, and deviation from it appeared eccentric or provocative, even when grounded in principled conviction.

Normalization also altered how dissent was perceived by peers, not just by authorities. Those who declined to participate disrupted the rhythm of civic life and drew attention to themselves precisely because participation had become routine. Refusal was experienced as social friction, a breach of communal expectations that others had learned to navigate with ease. This shift mattered profoundly. Noncompliance no longer appeared as a dispute between individual conscience and imperial authority but as a failure to uphold shared civic habits. In this way, the burden of enforcement migrated outward. Communities increasingly policed themselves, interpreting refusal as stubbornness, arrogance, or antisocial behavior rather than as a defensible moral stance.

The embedding of loyalty rituals in education and civic space produced a powerful but unstable equilibrium. The system functioned smoothly as long as participation remained unproblematic for most citizens and could be absorbed without moral cost. Where religious or ethical commitments made participation impossible, however, normalization intensified conflict rather than resolving it. What had been designed to produce cohesion instead magnified difference, sharpening boundaries between conformists and dissenters. By training citizens to equate belonging with ritual performance, the Roman state narrowed the space for conscientious refusal and transformed moral disagreement into civic estrangement. The very mechanisms that sustained everyday order prepared the ground for loyalty to fracture along lines the state could neither fully control nor easily repair.

Refusal as Disobedience: Jews, Christians, and the Limits of Tolerance

The limits of Roman tolerance became most visible when ritual participation intersected with communities for whom such acts carried unambiguous religious meaning. Jews and later Christians did not object to Roman rule as a political structure, nor did they generally refuse civic obligations such as taxation or legal compliance. Their resistance centered on ritual acts that they understood as violations of exclusive religious commitments. Sacrifice to the emperor, participation in imperial oaths, or gestures of veneration crossed a boundary that could not be negotiated without theological compromise. What Rome perceived as minimal civic gestures were, for these communities, acts of worship.

Roman authorities struggled to interpret this refusal within existing legal and cultural frameworks. The empire prided itself on religious pluralism, yet this pluralism was conditional. It extended to belief and practice so long as participation in public rituals was maintained. Jewish exemptions, where they existed, were pragmatic accommodations rather than principled recognitions of conscience. Christians, lacking the antiquity and ethnic coherence that sometimes shielded Jewish communities, were afforded even less latitude. Their refusal appeared inexplicable to Roman officials precisely because it disrupted the assumed separation between belief and civic action. To decline ritual participation was not merely unusual. It was unintelligible within the logic of Roman governance.

As a result, refusal was reframed as disobedience. Roman legal responses focused less on theological deviation than on obstinacy and procedural compliance. Officials repeatedly emphasized the opportunity to conform, offering dissenters multiple chances to perform the required acts and framing compliance as a simple administrative resolution. Persistence in refusal was treated as evidence of stubbornness, irrationality, or hostility to social order. The issue was not what dissenters believed but their unwillingness to resolve conflict through visible acts of loyalty. This framing allowed the state to present coercion as measured and reasonable, even benevolent, while recasting punishment as the consequence of choice rather than conviction. By shifting attention from belief to behavior, Roman authorities transformed moral dissent into a problem of discipline, stripping conscience of political legitimacy and redefining it as a disruptive refusal to cooperate.

The consequences of this reframing were profound. By interpreting principled refusal as civic threat, the Roman state transformed moral dissent into a problem of order. Loyalty became conditional on ritual performance, and tolerance was reduced to a narrow allowance for private belief divorced from public action. This approach hardened the identities of dissenting communities rather than integrating them. The attempt to enforce unity through ritual compliance exposed the fragility of a system that could accommodate difference only so long as it remained invisible. When conscience insisted on visibility, the limits of tolerance were revealed.

The Rhetoric of Unity and Order

Roman officials consistently framed the imperial cult as a mechanism of harmony rather than domination. Public statements, inscriptions, honorific decrees, and administrative correspondence emphasized peace, stability, and shared prosperity as the cult’s primary aims. Participation was cast as a civic gesture that bound diverse populations into a single political community without erasing local customs or identities. In provincial contexts especially, this rhetoric was deployed to reassure local elites that imperial rituals were instruments of inclusion rather than subjugation. By presenting the cult as a guarantor of order and continuity, Roman authorities sought to naturalize participation as an act of civic goodwill, a contribution to public peace, rather than a submission to centralized power. Unity, in this language, appeared not as an imposed condition but as a collective achievement sustained through shared ritual action.

This rhetoric relied heavily on the claim that imperial rituals were political rather than religious in nature. Officials insisted that sacrifice and honorific acts signified respect for Roman authority and gratitude for imperial benefaction, not theological assent to the emperor’s divinity. The emperor’s sacral status functioned as a symbolic condensation of imperial presence, protection, and beneficence rather than a demand for personal belief. By emphasizing symbolism over belief, Roman authorities framed ritual participation as administratively neutral and ideologically minimal. In this construction, compliance required no inner transformation, only outward acknowledgment. Refusal appeared irrational or antagonistic. If the rituals were merely civic courtesies, resistance could be interpreted only as rejection of social order itself rather than as an expression of conscience.

The language of unity also functioned to obscure asymmetries of power. By emphasizing order and concord, Roman authorities displaced attention from the coercive mechanisms that underwrote ritual participation. Unity was depicted as a shared achievement rather than an enforced condition. Those who declined to participate were portrayed not as victims of compulsion but as sources of disorder. The rhetoric converted structural inequality into moral failure, recasting dissenters as threats to communal stability rather than as individuals asserting conscience.

This discourse revealed its own contradictions. The insistence that unity required uniform ritual participation exposed the fragility of a system that could tolerate difference only when it remained performatively invisible. By equating order with conformity, Roman rhetoric transformed dissent into disloyalty and disagreement into danger. The appeal to unity did not resolve conflict but reframed it in moralized terms that justified exclusion and punishment. In claiming to preserve harmony, the state narrowed the boundaries of legitimate belonging and undermined the very cohesion it professed to defend.

Fractured Loyalty: Why Coercion Failed

Despite its administrative efficiency, the imperial cult failed to produce the durable loyalty it was designed to secure. Outward conformity masked underlying tensions rather than resolving them. Ritual compliance could be extracted through social pressure and legal threat, but such compliance did not reliably translate into genuine allegiance. Where participation felt imposed rather than meaningful, it fostered resentment, suspicion, and quiet resistance. The appearance of unity concealed a growing disconnect between obedience and loyalty.

Coercion also altered the social meaning of participation itself. When ritual acts became compulsory, they ceased to function as expressions of shared commitment and instead became markers of survival within an unequal system. Compliance increasingly signaled prudence rather than devotion, calculation rather than belonging. This shift weakened the symbolic power of the rituals, hollowing them out even for those who performed them willingly. As participation lost its expressive value, it also lost its integrative force. Rituals designed to bind communities together instead became reminders of constraint, teaching citizens how to navigate authority rather than how to trust it. Loyalty expressed under pressure became ambiguous, its sincerity increasingly difficult to discern even by those who demanded it.

For dissenting communities, coercion had the opposite of its intended effect. Rather than dissolving difference, it intensified group identity and sharpened internal boundaries. Refusal to participate became a defining marker of faithfulness, reinforcing communal narratives of moral endurance and distinctiveness. Jews and Christians came to understand noncompliance not as marginal eccentricity but as a central feature of collective identity, one that distinguished them sharply from surrounding civic culture. The state’s insistence on ritual performance transformed disagreement into durable opposition. By repeatedly forcing individuals to choose between conscience and compliance, Roman authorities elevated refusal into a powerful symbol of loyalty to an alternative moral order, embedding resistance within the very communities the cult was meant to absorb.

In the long term, the imperial cult revealed the structural weakness of loyalty systems built on compulsion. Stability achieved through enforced participation proved fragile, requiring continual reinforcement and escalating pressure. The Roman state learned that allegiance cannot be manufactured through ritual alone. When loyalty is demanded rather than earned, it becomes performative without being persuasive, and unity fractures along the very lines coercion was meant to erase.

From Imperial Cult to Civic Heritage

The Roman imperial cult did not disappear with the decline of pagan sacrifice, nor did its underlying logic vanish with the formal separation of church and state in later political systems. What endured was a governing strategy: the reclassification of morally charged practices as neutral civic obligations. In Rome, rituals honoring the emperor were framed as expressions of political order rather than religious devotion, allowing the state to demand participation while denying that it was regulating belief. In modern contexts, a similar maneuver appears when religious narratives, symbols, or texts are recast as cultural inheritance or civil tradition. The shift in language masks continuity in function. What changes is not the mechanism of power but the justificatory frame through which participation is enforced. By presenting ritual as heritage, the state claims legitimacy while insulating itself from accusations of coercion.

This reframing depends upon a critical distinction between belief and participation. By presenting certain religious stories, symbols, or texts as civic heritage, the state claims to avoid regulating belief while still mandating exposure, affirmation, or incorporation. Participation is described as educational, historical, or patriotic rather than devotional. As in Rome, the insistence is that no one is being asked to believe, only to acknowledge. Yet acknowledgment itself carries meaning. When the state determines which narratives count as shared heritage, it exercises power over the symbolic boundaries of belonging.

The designation of religious material as civic heritage also alters how dissent is interpreted. Objection is no longer framed as a matter of conscience but as resistance to shared history or national identity. Those who decline participation are cast not as religious minorities protecting belief but as civic outliers rejecting common culture. This rhetorical move mirrors Roman interpretations of ritual refusal as social defiance rather than moral integrity. By shifting the frame from religion to heritage, the state narrows the space in which dissent can be recognized as legitimate without appearing oppositional.

Education becomes the primary site where this logic is enacted. Curricula that incorporate religious narratives under the banner of cultural literacy or historical tradition replicate the Roman strategy of normalization through repetition. Students encounter these materials not as contested beliefs but as settled components of civic knowledge, often stripped of theological context while retaining moral authority. As with imperial rituals, the issue is less what is taught than how participation is structured. When engagement is mandatory, alternatives are constrained, and opt-outs are stigmatized, the line between education and enforcement begins to blur. What appears as neutral instruction can function as compelled acknowledgment, shaping civic identity through exposure that cannot be declined without consequence.

The Roman experience offers a cautionary lens for evaluating these modern developments. Rome believed it could preserve unity by abstracting ritual from belief and redefining participation as civic courtesy rather than religious obligation. Instead, it revealed the fragility of unity built on compelled acknowledgment. When modern states convert religion into heritage and dissent into disloyalty, they risk repeating the same structural error. Loyalty cannot be sustained by redefining conscience as obstruction or framing refusal as cultural rejection. The more insistently participation is described as neutral, the more revealing refusal becomes, and the more sharply unity fractures along moral lines that administrative language cannot reconcile.

Education as the New Ritual Space

As overt religious ritual receded from formal governance in many modern states, education emerged as a central site for the symbolic work once performed by temples and civic ceremonies. Schools occupy a unique position within political systems because they are simultaneously instruments of instruction and mechanisms of social formation. Like Roman civic spaces, they shape not only what individuals know but how they learn to belong. When the state seeks to normalize particular narratives, values, or symbolic frameworks, education provides a durable and ostensibly neutral venue for doing so.

In this context, ritual does not take the form of sacrifice or procession but of structured exposure, repetition, and sanctioned interpretation. Curricula establish which stories are foundational, which texts are authoritative, and which moral frameworks are presented as culturally essential. Participation is mandatory by design. Students do not choose whether to encounter these materials, and their engagement is assessed, graded, and institutionalized. The ritualized element lies not in belief but in performance: reading, reciting, analyzing, and affirming designated narratives as markers of civic competence. These repeated acts train students to treat certain symbolic materials as unquestionable fixtures of public life, even when their origins remain religious or sectarian in character.

This transformation mirrors Roman strategies of loyalty formation with striking precision. Just as imperial rituals were embedded in the rhythms of public life, modern educational practices embed symbolic participation in the routines of schooling. Morning assemblies, curricular standards, required readings, and standardized assessments function as mechanisms through which shared narratives are enacted rather than debated. The goal is familiarity and normalization, not persuasion. Repetition converts exposure into expectation, and expectation into assumption. What begins as instruction gradually becomes atmosphere, shaping the boundaries of acceptable civic identity without requiring overt enforcement. Students learn not only what is valued but what is taken for granted, absorbing a sense of civic normalcy that renders alternative perspectives marginal or disruptive before they are ever explicitly contested.

The classification of religious material as educational content intensifies this effect. When religious narratives are presented as historical foundations, moral touchstones, or elements of cultural literacy, they acquire institutional authority without requiring explicit assent. The claim is not that students must believe, but that they must learn. Yet learning is never neutral. Framing decisions determine whether materials are contextualized, contested, or insulated from critique. As in Rome, the state distinguishes belief from participation while insisting upon the latter, thereby exercising influence over conscience indirectly. The effect is subtle but cumulative. Symbolic participation becomes unavoidable, while dissent is procedurally constrained by grading systems, curricular mandates, and institutional norms that reward compliance and discourage sustained objection.

Dissent within this framework becomes especially difficult to articulate. Objection is no longer framed as resistance to religious imposition but as opposition to education itself. Parents and students who resist compulsory engagement are often portrayed as hostile to knowledge, tradition, or civic unity rather than as defenders of pluralism. This mirrors the Roman recoding of ritual refusal as antisocial behavior rather than principled dissent. The educational setting lends moral legitimacy to enforcement, allowing the state to present compulsion as pedagogical necessity. Social pressure reinforces this logic, as refusal becomes a signal of deviance rather than conscience, isolating dissenters within institutions that are structured to reward conformity.

The result is a system in which education functions as ritual space precisely because it is understood as non-ritual. Like the imperial cult, it operates most effectively when its symbolic power is least visible. Participation appears inevitable, dissent appears unreasonable, and loyalty is quietly measured through compliance. The Roman lesson applies with force. When education is used to compel symbolic participation under the guise of neutrality, it risks transforming conscience into deviance and belonging into performance. Unity produced in this way may appear stable, but it rests on foundations as fragile as those Rome once mistook for permanence. When moral disagreement insists on visibility, the system reveals its limits, and the rituals meant to sustain cohesion instead expose the fractures beneath it.

Dissent, Loyalty, and the Misreading of Refusal

States that rely on performative participation as a measure of loyalty routinely misinterpret refusal as rejection. Within such systems, dissent is not read as a principled stance grounded in moral or constitutional reasoning but as a failure of allegiance. The refusal to participate disrupts the symbolic economy through which belonging is measured, making it appear threatening regardless of intent. What is at stake is not simply disagreement but visibility. When loyalty is defined through public acts, abstention becomes legible only as negation, not as an alternative form of commitment.

This misreading is structural rather than accidental. Systems built around ritualized participation lack the conceptual tools to recognize dissent as loyal opposition because they collapse civic belonging into visible compliance. Roman officials could not interpret Jewish or Christian refusal as fidelity to a higher moral order because the imperial framework treated loyalty as an observable behavior rather than a moral relationship. Similarly, modern civic systems that frame participation in religiously inflected narratives as neutral heritage struggle to interpret refusal without moralizing it. The dissenter is cast as obstructive, antisocial, or hostile to unity, even when their objection is grounded in constitutional principle, religious freedom, or pluralistic commitment. In both cases, the system cannot accommodate dissent without destabilizing its own definition of loyalty.

The misinterpretation of refusal also reflects a deeper anxiety about control and predictability. Performative systems depend on repetition and regularity. When individuals refuse to perform expected acts, they introduce uncertainty into the symbolic order, calling attention to its constructed nature. This uncertainty is often resolved not through dialogue or accommodation but through suspicion and escalation. Refusal is treated as evidence of hidden motives, latent disloyalty, or future subversion. In Rome, this logic justified repeated demands for compliance and increasingly severe penalties framed as opportunities for reconciliation. In modern contexts, it legitimizes social stigma, administrative pressure, and legal contestation aimed less at persuasion than at restoring visible conformity.

Yet dissent frequently functions as a stabilizing force rather than a corrosive one. By refusing to participate in coerced symbolic acts, dissenters expose the boundaries of legitimate authority and force institutions to confront the limits of their claims to neutrality. Their refusal insists that loyalty cannot be reduced to performance and that civic belonging must accommodate moral difference without punishment. Historically, such refusals have prompted legal clarification, institutional reform, and more durable forms of inclusion precisely because they reveal contradictions that routine compliance conceals. Dissent, in this sense, serves as a diagnostic tool, testing whether a political order can sustain pluralism without demanding uniformity.

The Roman experience illustrates the long-term cost of misreading refusal. By treating conscientious dissent as civic defiance, the empire hardened identities and entrenched opposition it might otherwise have integrated. Modern states risk repeating this pattern when they conflate participation with loyalty and interpret abstention as disloyalty. A political order that cannot distinguish refusal from rejection mistakes conformity for cohesion. True loyalty does not require constant performance. It requires a civic framework capable of recognizing dissent as a form of engagement rather than a prelude to fracture.

Conclusion: When Unity becomes Fragile

The Roman imperial cult reveals the enduring risks of defining loyalty through compelled participation rather than voluntary commitment. What appeared to Roman authorities as a pragmatic solution to governing diversity ultimately exposed the fragility of unity built on ritual compliance. By insisting that loyalty could be measured through visible acts divorced from belief, the empire created a system that privileged conformity over trust. The result was not stable cohesion but a surface order that masked deep and persistent fault lines.

Across both ancient and modern contexts, the central error remains the same. States that convert morally charged practices into neutral civic obligations misunderstand the nature of allegiance. Loyalty is relational, not performative. It depends upon the recognition of conscience and the accommodation of difference within a shared political framework. When participation is enforced and refusal stigmatized, dissent ceases to function as a corrective force and instead becomes a marker of exclusion. Unity, under such conditions, becomes brittle, sustained only through repetition and pressure.

The Roman case demonstrates that compelled ritual does not eliminate disagreement but transforms it into identity. Communities forced to choose between conscience and compliance do not dissolve into the civic body. They harden their boundaries, internalize opposition, and carry dissent forward across generations. What begins as administrative convenience ends as moral polarization. The empire learned, too late, that loyalty extracted through coercion cannot survive the withdrawal of force that sustains it.

Modern states face the same temptation and the same danger. When governments reframe religious narratives as civic heritage and embed them within educational and public institutions, they risk repeating Rome’s mistake in secular form. Unity cannot be engineered by redefining conscience as obstruction or disagreement as disloyalty. A political order that endures is one that can tolerate visible refusal without fear. The Roman lesson is clear: unity secured by compulsion is always fragile, and the moment dissent insists on being seen, it begins to break.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- —-. The Matter of the Gods: Religion and the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- Apple, Michael W. Ideology and Curriculum. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. New York: Viking Press, 1968.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- —-. Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

- Downey, Glanville. “Education in the Christian Roman Empire: Christian and Pagan Theories under Constantine and His Successors.” Speculum 32:1 (1957): 48-61.

- Feldman, Noah. Divided by God: America’s Church-State Problem and What We Should Do About It. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

- Fraser, James W. Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Goodman, Martin. Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World, 31 BC–AD 337. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Moss, Candida R. The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. New York: HarperOne, 2013.

- North, John. “The Development of Religious Pluralism in the Roman Empire.” In The Jews among Pagans and Christians, edited by Judith Lieu, John North, and Tessa Rajak, 174–193. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Pascal, Nanette R. “The Legacy of Roman Education.” The Classical Journal 79:4 (1984): 351-355.

- Price, Simon R. F. Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Rawls, John. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Rawson, Beryl. Children and Childhood in Roman Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Rives, J. B. Religion and Authority in Roman Carthage: From Augustus to Constantine. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

- Scheid, John. An Introduction to Roman Religion. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Sullivan, Winnifred Fallers. The Impossibility of Religious Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Woolf, Greg. Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.06.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.