The history of Bible reading in American public schools demonstrates with unusual clarity that neutrality cannot be achieved through rhetoric alone.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Neutrality Is Claimed

In the nineteenth century, American public schools routinely opened the day with Bible readings, most often drawn from the King James Version. These practices were widely defended as nonsectarian, a term that suggested cultural consensus rather than religious imposition. School officials, Protestant leaders, and civic reformers insisted that such readings were morally instructive and socially unifying, not doctrinal. By presenting Protestant scripture as neutral heritage, they framed Bible reading as compatible with republican education and civic virtue.

This claim of neutrality, however, depended on a profound asymmetry of power that was rarely acknowledged by its proponents. What counted as nonsectarian was defined almost entirely by the dominant Protestant culture, whose theological assumptions were so deeply embedded in public institutions that they appeared universal rather than particular. The King James Bible was treated as a common moral text rather than a confessional document shaped by specific doctrinal choices. Catholic, Jewish, and later secular families experienced this presumption very differently. For them, Bible reading in schools was not a shared moral exercise but a state-sponsored endorsement of one religious tradition, imposed through compulsory attendance and backed by civic authority. The language of neutrality functioned less as an accurate description of educational practice than as a political shield, one that rendered Protestant norms invisible while marking dissent as abnormal.

Conflicts emerged precisely because neutrality was asserted rather than practiced. When minority families objected, their resistance was often framed as unreasonable, divisive, or even unpatriotic. Protestant defenders of Bible reading argued that the practice reflected the moral foundations of the nation and that opposition threatened social cohesion. This rhetoric inverted the dynamics of power at work. Coercion was rebranded as inclusion, while dissent was cast as hostility toward shared values. In this way, claims of neutrality transformed unequal authority into moral accusation, recasting minority objections as disruptions of public order rather than as protests against state-imposed religion.

What follows argues that the history of Bible reading in American public schools reveals a persistent and consequential pattern. Claims of cultural or moral neutrality have repeatedly been used to mask coercive religious practice, particularly when one tradition occupies a dominant social position. Far from resolving pluralism, these practices intensified conflict and exposed the instability of enforced consensus. The eventual constitutional rejection of school-sponsored religious instruction did not represent hostility to religion, nor did it signal a rejection of moral education. It reflected a growing recognition that neutrality cannot be achieved by declaring one tradition universal. When the state mandates religious content in education, neutrality is claimed in rhetoric but denied in practice, with consequences that shaped both social conflict and constitutional law in the United States.

The Rise of Common Schools and Protestant Assumptions

The common school movement of the nineteenth century was driven by a powerful civic ideal: the belief that public education could forge social unity in a rapidly changing nation. Reformers such as Horace Mann envisioned schools as engines of moral uplift, capable of disciplining the habits of the young while preparing them for democratic citizenship. In a society marked by immigration, urbanization, and class tension, common schools promised order, cohesion, and shared values. Education was framed not merely as a private good but as a public necessity, essential to the survival of the republic.

Yet the values embedded in these schools were far from neutral. The moral framework of the common school reflected the assumptions of the Protestant majority that dominated political and cultural life. Daily Bible readings, hymns, and moral lessons drawn from Protestant tradition were treated as universal ethical foundations rather than as expressions of a particular faith. Reformers insisted that these practices transcended denominational boundaries, presenting them as civic morality stripped of theology. In reality, they rested on a distinctly Protestant understanding of scripture, conscience, and moral authority.

The King James Bible occupied a central place in this educational vision, not only as a religious text but as a pedagogical tool. Its language shaped reading instruction, its narratives formed the basis of moral lessons, and its authority went largely unquestioned within the classroom. Because Protestantism functioned as the cultural default, the King James Bible appeared unmarked and natural, while alternative translations or traditions were rendered sectarian by contrast. Catholic objections to the use of the King James Version were dismissed as unreasonable demands for special treatment rather than recognized as principled dissent. In this way, the common school normalized one religious tradition by embedding it in routine practice, allowing Protestant assumptions to operate invisibly under the banner of neutrality.

These assumptions were reinforced by the broader political goals of the common school movement. Reformers believed that shared schooling would assimilate immigrants and instill loyalty to American institutions. Protestant-inflected instruction was seen as a civilizing force, capable of transforming diverse populations into disciplined citizens. Resistance to this project was interpreted as resistance to Americanization itself. Educational uniformity was equated with civic loyalty, and religious difference was framed as a barrier to national cohesion.

By embedding Protestant norms within compulsory education, common schools institutionalized a hierarchy of belief under the guise of universality. What was presented as common morality functioned as enforced conformity, privileging one tradition while marginalizing others. The promise of shared schooling rested on unequal terms of inclusion, offering participation only to those willing to accept the dominant religious framework. These dynamics laid the groundwork for later conflicts, as minority communities increasingly recognized that public education was being used not simply to teach civic skills but to define which beliefs were compatible with full membership in the nation.

“Nonsectarian” Christianity as Civic Religion

By the mid-nineteenth century, Protestant Christianity had come to function in American public schools not merely as a religious tradition but as a form of civic religion. Its practices, texts, and moral assumptions were embedded so deeply into educational routines that they appeared synonymous with public virtue itself. Bible reading, prayer, and moral instruction were presented as essential to the formation of disciplined, upright citizens rather than as acts of worship tied to a particular creed. This framing was crucial. By redefining religious practices as civic habits, reformers could embed Protestant norms into public education while insisting they were serving the republic rather than advancing a faith. Protestantism operated as an unspoken moral grammar for public life, shaping ideas of character, order, and belonging without naming itself as a confessional system.

The term nonsectarian played a crucial rhetorical role in this process. It suggested neutrality while concealing exclusion. Protestant leaders argued that because the Bible was read without commentary, it did not impose doctrine. Yet this claim ignored the fact that the selection of the King James Bible, the structure of readings, and the surrounding moral lessons all reflected Protestant theology. Neutrality was defined not by the absence of religious content but by the absence of Catholic or explicitly denominational interpretation. What counted as sectarian was determined by deviation from the Protestant norm.

This construction of Protestantism as universal had powerful social consequences. By treating one religious tradition as the cultural baseline, schools rendered other traditions visible as differences rather than as equally legitimate perspectives. Catholic, Jewish, and later secular students were placed in the position of outsiders within institutions that claimed to serve all. Their objections were interpreted not as challenges to coercion but as refusals to participate in shared civic life. Protestantism, recast as civic religion, became the moral language of belonging.

Defenders of Bible reading frequently argued that removing scripture from schools would erode public morality and threaten social order. These claims echoed earlier confessional arguments that religion was indispensable to civic discipline and social stability. By equating Protestant scripture with ethical instruction itself, reformers transformed a particular tradition into a prerequisite for citizenship. Moral disagreement was reframed as moral deficiency, and resistance to religious practices was cast as hostility toward virtue, order, and the common good. In this way, dissenting families were positioned not merely as religious minorities but as civic liabilities whose objections endangered the moral fabric of the nation.

This civic-religious framing also insulated Protestant practices from scrutiny in law and politics. Because Bible reading was presented as cultural inheritance rather than religious imposition, it was shielded from the kinds of constitutional challenges typically directed at formal establishments of religion. The category of civic religion allowed the state to sponsor religious practice while denying that sponsorship was occurring. Protestantism functioned as an unofficial establishment, sustained not through explicit legislation but through custom, habit, and majoritarian power. Its dominance was rendered invisible precisely because it was normalized.

The endurance of “nonsectarian” Christianity as civic religion reveals how deeply religion can shape public institutions without formal establishment. By embedding Protestant norms within education, the state taught generations of students that certain beliefs were synonymous with civic virtue and national identity. This arrangement did not resolve religious diversity but managed it by subordinating minority traditions to a dominant moral framework. The resulting unity depended on silence and compliance rather than equal inclusion, producing a public culture that appeared cohesive while resting on structural exclusion.

Catholic Resistance and the Limits of Tolerance

Catholic opposition to Bible reading in public schools exposed the practical limits of nineteenth-century American claims to religious tolerance. As Catholic immigration increased, particularly from Ireland and Germany, Catholic families encountered a public school system that insisted it was neutral while enforcing Protestant norms. Objections were not initially framed as demands for privilege but as protests against coercion. Catholics objected to the use of the King James Bible, arguing that it embodied Protestant translation choices and theological assumptions incompatible with Catholic doctrine. These objections challenged the foundational claim that Bible reading was merely moral instruction rather than confessional practice.

Protestant responses to Catholic resistance were revealing. Rather than acknowledging the sectarian nature of the King James Bible, defenders of the common schools insisted that Catholic objections were unreasonable and disruptive. Catholics were accused of undermining social unity, threatening republican values, and refusing to assimilate. Tolerance, it became clear, was conditional. It extended only so far as minorities accepted the dominant religious framework. When Catholic families asked for accommodation or alternative arrangements, their requests were portrayed as assaults on the common school ideal itself.

This dynamic transformed religious disagreement into a political problem. Catholic resistance was not treated as a matter of conscience but as evidence of divided loyalty. Public officials and Protestant leaders warned that Catholic influence would fragment the nation, placing obedience to church authority above allegiance to the state. Schools became the front line in this struggle. By insisting on Protestant Bible reading as a condition of participation, authorities forced Catholic families to choose between conformity and exclusion, reinforcing the idea that civic membership required religious alignment.

In many cities, Catholic resistance eventually led to the creation of parallel institutions. Catholic communities established parochial schools not as an initial rejection of public education, but as a defensive response to its coercive character. These schools emerged because Catholic parents recognized that participation in the public system required daily exposure to religious practices they could not in good conscience accept. Yet the formation of parochial schools was frequently condemned as separatist, divisive, or even subversive. Catholic efforts to preserve religious autonomy were framed as threats to national unity, while Protestant control of public institutions went largely unquestioned. This double standard revealed how deeply Protestant norms were assumed to define the public sphere itself.

The Catholic challenge ultimately exposed a central contradiction in the common school project. Reformers celebrated public education as a mechanism for unifying a diverse population, yet that unity depended on enforcing a specific religious norm. Catholic resistance made visible what had previously been obscured by claims of neutrality: inclusion was conditional upon acceptance of Protestant practices. The limits of tolerance were reached not when Catholics sought to impose their beliefs on others, but when they refused to submit to a system that treated Protestantism as universal culture. In this sense, Catholic opposition did not undermine pluralism. It revealed how little pluralism the common school system was prepared to tolerate when confronted with genuine religious difference.

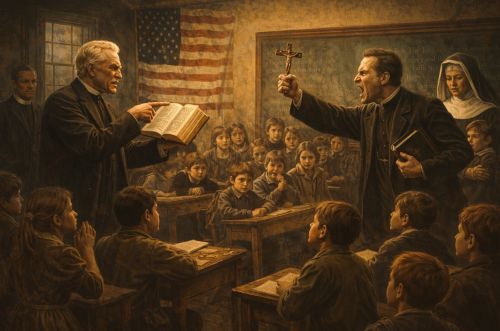

The Philadelphia Bible Riots and Violent Enforcement

The tensions surrounding Bible reading in public schools reached their most explosive expression in the Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844. What had long been defended as a neutral educational practice was revealed, under pressure, as a deeply contested exercise of power embedded in ethnic, religious, and political conflict. Rumors circulated that Catholic leaders sought to remove the Bible from public schools, igniting Protestant fears that the moral foundations of the nation were under attack. In reality, Catholic objections focused narrowly on the compulsory use of the King James Bible, which Catholics regarded as a Protestant translation carrying doctrinal assumptions they could not accept. That distinction, however, collapsed in the public imagination. Resistance to Protestant norms was recast as opposition to Christianity itself, and by extension as hostility to American civic life.

The riots exposed how claims of neutrality masked a readiness to enforce religious dominance through violence when persuasion and habit failed. Protestant mobs attacked Catholic neighborhoods, churches, and schools, burning property, looting homes, and killing residents. State militia units were eventually deployed, but only after significant destruction and loss of life had already occurred. Local authorities proved either unwilling or unable to intervene decisively, and in some cases appeared sympathetic to the rioters’ grievances. This failure of protection underscored the extent to which Protestant norms were treated as synonymous with public order and civic legitimacy. Violence functioned as an extension of the same logic operating in classrooms: Protestant practices were defended as universal, and resistance was treated not as dissent but as provocation.

What makes the Philadelphia riots particularly revealing is that they erupted in defense of a practice officially framed as noncoercive. Bible reading in schools was supposedly about moral instruction, not religious enforcement. Yet when challenged, its defenders responded not with argument but with force. This contradiction exposed the fragility of the neutrality claim. A practice that required violence to sustain itself could not plausibly be described as consensual or culturally shared. The riots demonstrated that Protestant civic religion was maintained not only through habit and rhetoric but through the threat of exclusion and physical harm.

In the aftermath of the riots, some school districts quietly reconsidered compulsory Bible reading, recognizing that enforced uniformity carried unacceptable costs. Others doubled down, interpreting violence as proof of the need for stronger moral discipline rather than as evidence of injustice. Either way, the riots left a lasting mark on American debates over religion and education. They made visible the stakes of state-sponsored religious practice and exposed the dangerous consequences of treating one tradition as the moral default. The riots stand as a stark reminder that when neutrality is claimed but power is unevenly distributed, education can become a flashpoint for conflict rather than a vehicle for unity.

Jewish, Secular, and Minority Objections

While Catholic resistance to Protestant Bible reading was the most visible and politically organized, it was far from the only form of dissent. Jewish families, secular reformers, and members of smaller Christian denominations also experienced public school religious practices as exclusionary rather than unifying. For Jewish students in particular, the daily reading of the King James Bible underscored that public education was structured around a Christian moral framework that assumed their absence. Participation required either silent acquiescence to religious language that was not their own or visible difference that marked them socially. In either case, the message was clear: public schools were common only on terms defined by the Protestant majority.

Jewish objections were often articulated in constitutional and civic terms rather than doctrinal ones. Unlike Catholics, who challenged the use of a specifically Protestant translation of scripture, Jewish families objected to the presence of Christian religious instruction in state institutions altogether. Bible reading was not experienced as generic morality or shared heritage but as an implicit affirmation of Christian narrative, authority, and cultural dominance. Jewish students were marked as outsiders not because they refused to participate, but because the curriculum presumed a religious background they did not share. In this way, so-called nonsectarian practices reinforced Christian normativity while rendering Jewish identity perpetually marginal within institutions that claimed to serve all citizens equally.

Secular objections followed a similar logic. As the nineteenth century progressed, a growing number of Americans questioned whether any religious instruction belonged in public schools. Freethinkers, humanists, and advocates of church-state separation argued that moral education did not require scripture and that state-sponsored religion violated individual conscience. These critics were often dismissed as hostile to religion itself, echoing the pattern seen in Catholic resistance. Opposition to Bible reading was interpreted not as a defense of pluralism, but as moral deficiency or civic irresponsibility.

Other minority Christian groups also found themselves at odds with Protestant defaults. Quakers, Unitarians, and members of emerging denominations objected to specific theological assumptions embedded in Bible readings and accompanying instruction. Yet their protests were rarely accommodated. The logic of the common school required uniformity, and deviation from the dominant Protestant framework was treated as disruption. Minority Christian objections revealed that the issue was not interreligious difference alone, but the state’s insistence on a single moral narrative as the basis of public education.

These objections exposed the structural flaw at the heart of claims of nonsectarianism. The problem was not simply that one religious group objected, but that multiple, distinct communities experienced the same practices as coercive and exclusionary. Jewish, secular, and minority Christian dissent demonstrated that Protestant Bible reading functioned as a boundary-making practice, defining who counted as a full participant in civic life and who did not. Their resistance broadened the debate beyond denominational rivalry and helped shift public discussion toward constitutional principles of equality and conscience. By making visible the exclusions produced by so-called neutral practices, these objections laid critical groundwork for the legal and cultural reassessment of religion in public education.

Courts Confront the Fiction of Neutrality

As conflicts over Bible reading intensified throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, courts were gradually forced to confront the widening gap between claims of nonsectarianism and the lived experience of coercion in public schools. Early legal challenges rarely produced decisive rulings against Bible reading. Many judges shared the cultural assumptions of the Protestant majority and regarded scripture as a benign moral influence rather than a religious imposition. Courts were hesitant to treat the issue as a constitutional matter, often framing disputes as questions of local control or school board discretion. Neutrality was presumed rather than interrogated, and long-standing custom carried significant legal weight. This judicial reluctance allowed Protestant practices to persist under the cover of tradition, even as social conflict intensified.

Repeated litigation exposed the instability of this position. Minority plaintiffs increasingly argued that compulsory Bible reading violated core principles of religious liberty by forcing students to participate in exercises that affirmed beliefs they did not share. Courts began to recognize that neutrality could not be defined simply by the absence of denominational labels or overt theological instruction. The legal focus shifted from whether Bible reading was explicitly sectarian to whether the state was compelling religious exercise at all. This reframing marked a critical turning point, as judges began to acknowledge that majoritarian practices, even when longstanding, could operate as instruments of coercion.

State courts were often the first to articulate this emerging understanding. Decisions in states such as Wisconsin and Ohio acknowledged that Bible reading, even without commentary, constituted religious instruction when mandated by public authorities. Judges increasingly recognized that allowing students to opt out did not resolve the constitutional problem. Exemptions singled out dissenters, marked them publicly as different, and subjected them to social pressure that undermined the voluntariness of participation. By examining how these practices functioned in real classrooms rather than how they were described rhetorically, courts began to dismantle the fiction that neutrality could coexist with compulsion.

These developments laid the groundwork for later federal rulings that would decisively reject school-sponsored religious practices. By the mid-twentieth century, courts increasingly accepted that the state could not endorse religious exercises under the guise of culture, morality, or tradition without violating the First Amendment. This shift did not reflect hostility toward religion, but a clearer understanding of equality and conscience in a pluralistic society. Neutrality, the courts concluded, required the absence of state-imposed religious practice rather than its universalization. In confronting the fiction of nonsectarianism, the judiciary helped redefine religious freedom as protection from coercion rather than accommodation of dominance.

From Custom to Constitution: The First Amendment Clarified

The transition from customary practice to constitutional principle marked a decisive shift in how American law understood religion in public education. For much of the nineteenth century, Bible reading persisted not because it had been rigorously justified under constitutional scrutiny, but because it was familiar, widespread, and supported by the cultural authority of the Protestant majority. Custom functioned as a substitute for legality. As long as a practice appeared traditional and popular, it was assumed to be compatible with republican governance, even when it produced sustained conflict and exclusion.

This reliance on custom began to erode as courts confronted the cumulative effects of religious coercion in schools. Judges increasingly recognized that constitutional guarantees could not be subordinated to habit, especially when that habit systematically privileged one religious tradition over others. Legal reasoning shifted away from deference to local norms and toward an examination of how state practices operated in reality. The First Amendment’s religion clauses, long treated as narrow limits on federal interference, came to be understood as articulating a broader principle of religious liberty applicable to public institutions. The key question was no longer whether Bible reading had always been done, but whether it could be reconciled with the constitutional promise of equal citizenship in a pluralistic society.

Incorporation played a critical role in this transformation. As the Supreme Court began applying the First Amendment to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, disputes over public education acquired new constitutional weight. Practices once defended as matters of local discretion were now subject to national standards of religious neutrality. This shift forced courts to acknowledge that state-sponsored religious exercises, even when framed as cultural or moral instruction, implicated fundamental rights. Tradition alone could no longer insulate schools from constitutional review, and the authority of custom gave way to the authority of constitutional principle.

Mid-twentieth-century Supreme Court decisions crystallized this evolving understanding. In cases addressing school prayer and Bible reading, the Court explicitly rejected the argument that long-standing or widely accepted practices were constitutional. Instead, it emphasized that the Establishment Clause prohibited the state from composing, endorsing, or organizing religious exercises within compulsory educational settings. The Court made clear that neutrality could not be achieved by treating one religious tradition as universal or culturally foundational. Constitutional neutrality required the state to refrain from religious instruction altogether, not to repackage it in secular or civic language.

Crucially, these rulings also reshaped the meaning of religious freedom itself. Freedom was no longer understood as the state’s obligation to accommodate or balance competing religious expressions within public schools, a framework that would inevitably privilege the majority. Instead, it was defined as freedom from state-imposed religious practice. The Court acknowledged that even ostensibly voluntary participation in a compulsory environment carried coercive force, particularly for children and religious minorities. Opt-out provisions and parental consent were deemed insufficient because they placed the social and psychological burden of dissent on students rather than on the state that imposed the practice.

By clarifying the First Amendment’s application to public education, courts transformed religion in schools from a matter of inherited custom into one of constitutional principle. This transformation did not remove religion from public life, nor did it deny its social importance. It established a boundary around state authority, recognizing that pluralism cannot be sustained through enforced consensus. When the state abandons tradition in favor of constitutional clarity, it affirms that civic unity is best preserved not by mandating shared belief, but by protecting the freedom to differ.

Why “Just Cultural” Has Always Failed

The claim that Bible reading in public schools is “just cultural” has surfaced repeatedly whenever state-sponsored religious practices come under scrutiny. Defenders have argued that scripture functions as shared heritage rather than belief, moral reference rather than doctrine, and tradition rather than worship. This framing has proven attractive because it allows religious content to remain embedded in public institutions while avoiding the legal and political consequences of explicit establishment. Yet across time and place, this argument has collapsed under examination. History shows that culture, when enforced by the state through compulsory institutions, ceases to be descriptive. It becomes prescriptive. What is framed as cultural inheritance becomes an obligation imposed on those who may not share it.

One reason the “just cultural” argument fails is that culture is never neutral when embedded in compulsory institutions. Public schools do not merely reflect society; they actively shape norms, identities, and hierarchies of belonging. When a particular religious text is presented as cultural baseline, it implicitly defines what is normal and what is deviation. Students who share that background experience affirmation and invisibility, while others experience pressure to conform or the burden of standing apart. The state’s insistence that participation is cultural rather than religious does nothing to change the underlying dynamic. Compulsion remains compulsion, regardless of the language used to describe it.

Courts eventually recognized that cultural framing could not dissolve coercion. Even when scripture was presented without commentary or ritual embellishment, its presence carried religious meaning precisely because of its source and content. Judges came to understand that the power of the state transforms context. A Bible read in a classroom is not the same as a Bible read at home, in church, or within a voluntary association. The institutional setting matters. What the state selects, schedules, and mandates acquires official significance regardless of how carefully it is labeled.

The persistence of the cultural argument also reveals a deeper misunderstanding of pluralism. Cultural majorities often experience their own traditions as background rather than belief, making it difficult to recognize how those traditions function as impositions when universalized. What feels like shared heritage to one group feels like enforced participation to another. History demonstrates that invoking culture does not resolve this tension. It merely obscures it, postponing reckoning until conflict, resistance, or litigation forces the issue into the open.

Ultimately, the failure of the “just cultural” defense reflects a structural reality that has repeated itself with remarkable consistency. The state cannot sponsor religious content in compulsory education without taking sides, no matter how carefully that content is rebranded. Courts did not reject cultural arguments because they were hostile to tradition or moral instruction. They rejected them because tradition backed by state authority becomes obligation, and obligation erodes freedom of conscience. Neutrality is not achieved by relabeling belief as culture or by insisting that everyone participate equally. It is achieved by removing the state from the business of religious instruction altogether. Every historical attempt to bypass this principle has produced the same result: exclusion, social conflict, and eventual constitutional correction.

Conclusion: Neutrality Is Not Performance

The history of Bible reading in American public schools demonstrates with unusual clarity that neutrality cannot be achieved through rhetoric alone. For more than a century, Protestant practices were defended as cultural, moral, or civic rather than religious, even as they imposed tangible and enduring costs on minority communities. These practices survived not because they were neutral, but because they were normalized by institutional power and demographic dominance. When neutrality is asserted without being structurally enforced, it becomes a performance rather than a principle. The language of tradition, unity, and moral consensus served to obscure coercion, allowing unequal practices to persist while insulating them from critique.

What ultimately forced change was not a sudden hostility toward religion, but the cumulative recognition that state authority transforms meaning. A religious text does not become neutral because it is familiar to the majority, nor does compulsion lose its coercive force because participation is framed as benign or optional. Courts eventually acknowledged what dissenting families had long understood through lived experience. When the state organizes, mandates, or endorses religious practices within compulsory education, it takes a position, regardless of intent or tone. Neutrality requires more than inclusive language or symbolic balance. It requires restraint, especially where power is asymmetrical and participation is compulsory.

This recognition reshaped American constitutional law by redefining religious freedom as protection from state-imposed belief rather than accommodation of dominant traditions. The move away from school-sponsored religious instruction did not drain public life of moral substance or ethical concern. Instead, it clarified the boundary between civic authority and personal conscience. By removing religion from the machinery of compulsory education, the state affirmed that unity cannot be manufactured through enforced ritual or shared recitation. It must be sustained through equal treatment, institutional humility, and genuine pluralism.

The recurring temptation to revive “just cultural” arguments in modern debates reveals how fragile these lessons remain. History shows that whenever the state attempts to reintroduce religious content under the guise of heritage, morality, or national tradition, the same patterns reappear. Minorities are asked to endure discomfort quietly, dissent is reframed as hostility, and power is mistaken for consensus. Neutrality is not achieved by broadening participation in a dominant tradition, nor by insisting that history excuses compulsion. It is achieved by refusing to convert belief into obligation. The enduring lesson of the Bible-reading battles is both simple and demanding. Neutrality is not something the state proclaims. It is something the state practices, most clearly, by knowing when not to act.

Bibliography

- Dolan, Jay P. The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

- Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

- Feldberg, Michael. The Philadelphia Riots of 1844: A Study of Ethnic Conflict. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975.

- Fraser, James W. Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- Green, Steven K. The Bible, the School, and the Constitution: The Clash That Shaped Modern Church-State Doctrine. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- —-. The Second Disestablishment: Church and State in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Griffin, Clifford S. Their Brothers’ Keepers: Moral Stewardship in the United States, 1800–1865. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1960.

- Hamburger, Philip. Separation of Church and State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Jorgenson, Lloyd P. “Historical Origins of Non-Sectarian Public Schools: The Birth of a Tradition.” The Phi Delta Kappan 44:9 (1963): 407-414.

- McConnell, Michael W. Religion and the Constitution. New York: Aspen Publishers, 2002.

- Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Sullivan, Winnifred Fallers. The Impossibility of Religious Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Tyack, David B. The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.06.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.