By attaching governance so completely to a single name, Mussolini created a regime that felt omnipresent, decisive, and materially productive in the short term.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Power Learned to Sign Everything

Fascism emerged in a political world already transformed by mass literacy, mass media, and mass administration. Authority no longer needed to be inferred from distance, lineage, or tradition. It could be printed, broadcast, inscribed, photographed, and endlessly reproduced. Newspapers, posters, radio, architecture, and bureaucratic paperwork created an environment in which power could be encountered constantly rather than episodically. In this setting, governance was no longer confined to lawmaking or enforcement. It became a matter of presence. The modern state acquired the capacity to saturate everyday life with names, images, and slogans that collapsed the boundary between public action and personal authorship. Fascism did not invent this condition, but it exploited it with unprecedented speed, coordination, and intent.

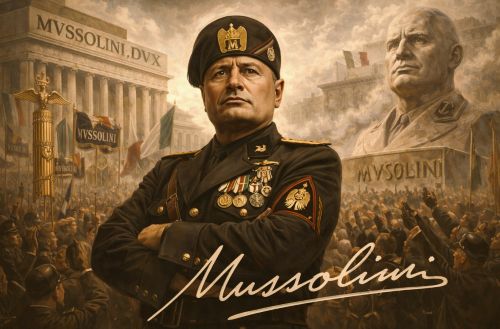

It was within this context that Benito Mussolini reconceived political authority as omnipresent signature. Rather than allowing institutions to mediate legitimacy in abstract or procedural ways, Mussolini attached his name and image directly to the visible operations of the state. Roads, schools, youth organizations, public buildings, newspapers, and official proclamations bore his imprint. Even initiatives framed as technical or developmental were rhetorically personalized. The effect was cumulative rather than dramatic. Citizens did not encounter the regime only in moments of crisis or ceremony, but in daily routines where order, movement, and material improvement already felt necessary. Benefit and authority became cognitively linked to a single personal source. The state still existed, but it increasingly appeared as Mussolini’s extension rather than as an independent structure.

This strategy marked a decisive break from earlier models of personal rule. Unlike Napoleon’s retreat into procedural invisibility or Louis XIV’s concentration of spectacle at court, fascist authority operated through saturation. Visibility itself became discipline. When the leader’s name appears everywhere, absence becomes unthinkable and dissent becomes deviant. Power no longer needed to persuade or even explain. It needed only to be seen repeatedly, in contexts where obedience and benefit already felt natural.

Fascist eponymy transformed the modern state into a platform for personal credit while hollowing its institutional core. By branding public goods as private achievement, Mussolini converted governance into authorship and citizenship into recognition. The result was a system that appeared strong because it was everywhere yet proved fragile because it could not survive the disappearance of its signature. When the state becomes a name, its durability depends entirely on the body that signs it.

After Liberal Failure: The Political Demand for Authoritative Presence

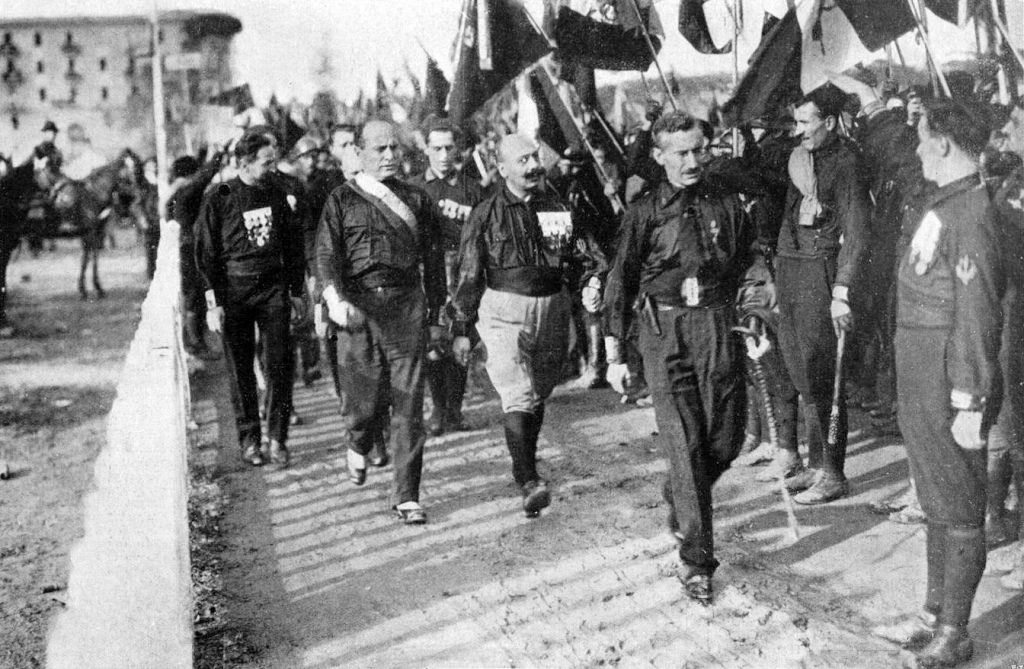

Italy’s turn toward fascism cannot be understood without reckoning with the perceived failure of liberal governance in the aftermath of World War I. Parliamentary institutions survived the war formally intact, but they emerged politically discredited. Coalition governments collapsed with regularity, legislation stalled, and the state appeared incapable of managing inflation, unemployment, or social unrest. To many Italians, liberalism came to signify weakness rather than liberty, indecision rather than pluralism. The state existed, but it did not appear to act.

This sense of paralysis was intensified by the social consequences of mass mobilization. Veterans returned from the front with expectations of recognition, employment, and stability that the liberal state struggled to meet. Widespread labor unrest, factory occupations, rural violence, and fears of socialist revolution created an atmosphere of permanent emergency. Parliamentary debate appeared detached from lived reality, while legal restraint seemed inadequate to the scale of disruption. The language of constitutional process offered little reassurance in a political culture increasingly shaped by urgency, spectacle, and the memory of wartime command. Authority that hesitated appeared complicit in disorder. Authority that deliberated appeared absent.

Visibility became a political demand. Italians did not merely want governance. They wanted to see it. The abstract legitimacy of institutions no longer satisfied a public conditioned by war, propaganda, and mass communication. Leadership needed to present itself as decisive, embodied, and unmistakable. The idea of an impersonal state lost credibility. What emerged instead was a hunger for presence, a belief that order required a visible human center capable of acting without delay.

Fascism answered this demand by reframing authority as personal certainty rather than institutional continuity. Mussolini did not initially abolish liberal structures. He overshadowed them. Parliamentary forms remained, but they were rhetorically diminished as obstacles to action rather than safeguards of legitimacy. Mussolini positioned himself as the interpreter of national urgency, capable of cutting through procedure to restore momentum. What mattered was not whether institutions persisted on paper, but whether they were perceived as effective in practice. Fascism converted political legitimacy from a question of lawful process into a question of decisiveness, measured by speed, clarity, and force of presence.

The collapse of confidence in liberalism thus created the conditions for eponymous power. When institutions lose credibility, personal authority rushes to fill the void. Fascism did not arise because Italians rejected the idea of the state. It arose because they no longer trusted the state to function without a face. Authoritative presence became the substitute for institutional trust, and in that substitution lay the foundation for the branded regime that followed.

Il Duce Everywhere: Industrial-Scale Name Saturation

Fascist authority operated through a logic of saturation rather than persuasion. Mussolini’s regime did not rely primarily on convincing citizens of ideological correctness. It relied on making the leader unavoidable. His name, image, and slogans were reproduced across newspapers, posters, public buildings, classrooms, workplaces, and civic rituals. The effect was cumulative. Citizens encountered Il Duce not as a distant ruler, but as a constant visual and linguistic presence woven into the fabric of daily life. Authority did not arrive episodically. It surrounded.

This saturation was made possible by modern technologies of reproduction. Advances in printing, photography, radio, and mass circulation allowed the regime to scale presence in ways earlier systems of personal rule could not. Mussolini’s portrait became a standardized object, reproduced with industrial efficiency and distributed through both state and quasi-private channels. Headlines spoke in his voice, collapsing reporting into declaration. Speeches were broadcast into homes, cafés, factories, and public squares, collapsing private and public space into a single auditory field. Even silence was structured around him, as newspapers left blank columns rather than publish dissenting views. Absence itself became another mode of presence, reinforcing the sense that nothing legitimate existed outside the leader’s voice.

Unlike traditional cults of personality, fascist saturation did not reserve reverence for exceptional moments. It normalized repetition. The leader’s name appeared in mundane contexts where admiration was neither demanded nor optional. Street signs, school texts, bureaucratic notices, and timetables quietly reinforced association without emotional escalation. This constant exposure trained recognition rather than devotion. Obedience became reflexive because the leader felt already familiar, already embedded in the environment, long before citizens were asked to consciously assent to fascist ideology.

The regime carefully calibrated tone to avoid exhaustion. Mussolini was not always exalted as heroic or mythic. Often he was presented as practical, energetic, and relentlessly active. Photographs showed him working late, inspecting construction sites, harvesting crops, piloting aircraft, or addressing crowds with blunt certainty. These images collapsed the distance between governance and labor, suggesting that administration itself flowed directly from the leader’s body. The implication was not merely that Mussolini commanded the state, but that he was its most efficient instrument. Authority appeared tireless, pragmatic, and physically present.

This omnipresence also disciplined perception. When authority appears everywhere, alternatives appear nowhere. Dissent was not merely suppressed through censorship or violence. It was crowded out cognitively. Competing narratives struggled to gain traction in an informational environment already saturated with a single signature. Citizens learned to navigate a world in which legitimacy was pre-labeled, where recognition preceded evaluation. The leader’s name became a shortcut for stability, progress, and national direction, reducing the need for independent judgment.

Mussolini transformed visibility into governance. The state no longer needed to explain itself. It only needed to display itself continuously. This strategy produced a regime that felt powerful not because it persuaded convincingly, but because it was impossible to escape. Authority succeeded by becoming the background condition against which all political meaning was measured.

Public Works as Personal Gift: Branding Abundance

Fascist eponymy reached its most effective form when material improvement was framed as personal beneficence. Public works were not presented as the outcome of state planning or collective effort, but as gifts flowing directly from Mussolini’s will. Roads, land reclamation projects, housing developments, and transportation networks were rhetorically individualized, their existence attributed to the leader’s foresight and energy. Infrastructure became evidence not of institutional capacity, but of personal generosity.

This personalization reshaped how citizens understood entitlement. In liberal systems, public works are ideally justified through taxation, representation, and administrative obligation. Under fascism, benefit was recoded as reward rather than right. The regime encouraged Italians to experience material improvement not as something owed by the state, but as something bestowed by Il Duce. Gratitude replaced expectation. Dependency replaced accountability. Citizens learned to measure political satisfaction not by policy durability or equity, but by visible favor. This shift fundamentally altered the relationship between citizen and state, making obedience feel reciprocal rather than coerced.

Land reclamation projects offer a clear example. The draining of marshlands and the creation of new agricultural settlements were celebrated as triumphs of fascist vitality. Mussolini’s image appeared prominently in ceremonies, inscriptions, and newsreels marking their completion. The technical labor of engineers and workers receded from view, replaced by narratives of decisive leadership conquering nature itself. The land did not improve because institutions functioned. It improved because Mussolini acted.

This framing insulated the regime from structural critique. Failures could be blamed on sabotage, inefficiency, or external constraint, while successes accrued symbolically to the leader. The uneven distribution of benefits mattered less than the visibility of action. Public works became spectacles of abundance, designed to demonstrate motion and productivity even when economic gains were limited or unsustainable. What mattered was not long-term capacity, but short-term perception. Infrastructure served as proof of vitality, even when maintenance and funding lagged behind the initial display.

Mussolini converted material policy into personal narrative on a national scale. Infrastructure ceased to be merely functional and became testimonial, a visible ledger of supposed achievement attributed to a single will. Roads, buildings, and reclaimed land did not simply facilitate movement or production. They told a story about who deserved credit for modernity itself. By personalizing improvement, the regime trained citizens to associate prosperity with obedience and to interpret governance through gratitude rather than rights. The state appeared active because the leader appeared everywhere, signing improvement into existence while quietly hollowing the institutional foundations that might have sustained progress without him.

Renaming Space: Streets, Youth, and National Memory

Fascist power extended beyond governance and infrastructure into the symbolic control of space itself. Renaming streets, plazas, schools, and public institutions was not a cosmetic exercise or an afterthought of regime consolidation. It was a deliberate strategy to reorganize national memory around fascism and its leader. Familiar places were stripped of older historical associations and reinscribed with new meaning that aligned past, present, and future with the regime’s narrative. Everyday geography was converted into ideological text. Space became narrative, and movement through Italy became a form of silent instruction. To inhabit the nation was to inhabit fascism’s version of history.

This spatial reordering reached deeply into the rhythms of daily life. Street names commemorated fascist milestones, martyrs, and slogans, embedding the regime’s preferred timeline into ordinary acts of orientation. Maps themselves became political artifacts, encoding legitimacy through repetition. Citizens could not give directions, receive mail, or identify civic locations without invoking fascist language. The power of this strategy lay in its banality. Memory was no longer activated only at monuments or anniversaries. It was triggered constantly, through habits so routine that they ceased to register as ideological at all. The regime did not need to remind people what mattered. The environment did it automatically.

Youth organizations amplified this process by linking renamed space to generational identity. Fascist youth groups occupied renamed buildings, marched through rebranded streets, and performed rituals in newly designated civic spaces. The regime understood that memory had to be learned early and bodily. By associating childhood experience with fascist geography, it sought to produce citizens for whom the regime felt foundational rather than imposed. History was not something taught. It was something inhabited.

Urban planning reinforced these effects by reshaping cities to align with fascist mythmaking. Ancient Rome was selectively resurrected, while inconvenient layers of medieval, Renaissance, or liberal history were demolished, obscured, or marginalized. Architecture framed fascism as both heir to and fulfillment of Roman greatness, collapsing past, present, and future into a single ideological arc. New boulevards, monumental axes, and cleared vistas created visual narratives of continuity and destiny. The city itself became a curated argument, legible only through fascist interpretation. Movement through space trained acceptance of the regime’s historical claims by making alternatives physically disappear.

Mussolini transformed geography into pedagogy. Streets, schools, and youth institutions no longer simply organized social life. They instructed it. National memory was no longer contested or plural. It was standardized, directional, and signed. By controlling the language of place, the regime ensured that history itself appeared to lead inexorably toward the fascist present, leaving little room to imagine alternatives.

Legal Publicness, Institutional Hollowing

Fascist Italy maintained the outward forms of legality even as it systematically stripped institutions of independent authority. Courts continued to function, ministries continued to issue regulations, and laws were formally enacted through recognizable procedures inherited from the liberal state. This continuity was not incidental. It was essential to fascist governance. By preserving legal form, the regime created the impression of a state governed by rules rather than by raw force. Citizens encountered familiar symbols of legality in daily life, from courtrooms to official decrees, reinforcing the sense that order persisted. Yet beneath this legal publicness, real decision-making increasingly bypassed institutional channels altogether. Authority flowed from Mussolini’s person, while institutions served primarily to formalize decisions already made elsewhere.

This hollowing did not require the destruction of bureaucracy. It depended on its subordination. Ministries became instruments rather than sites of deliberation. Judges applied law within boundaries shaped by political expectation rather than legal principle. Civil servants learned to anticipate the leader’s preferences and align action accordingly. The law remained visible, but its autonomy diminished. Institutions functioned as shells, preserving the appearance of legality while surrendering substantive independence.

The coexistence of legal form and personal rule proved politically effective. By retaining courts and statutes, the regime avoided the instability that open lawlessness produces. Citizens could still recognize familiar procedures and appeal to official channels, even as outcomes became increasingly predictable. This arrangement normalized authoritarian control by embedding it within recognizable structures. Power appeared restrained because it was procedural, even as procedure itself was emptied of resistance.

Mussolini achieved a balance between reassurance and domination. Institutions were neither abolished nor empowered. They were preserved as symbols while being deprived of agency. Legal publicness reassured the population that continuity and order endured, even as institutional hollowing ensured obedience without overt rupture. The state looked intact, disciplined, and lawful, but its center of gravity had shifted decisively from law to leader, leaving behind a governance structure capable of performing legality without ever practicing independence.

Training Association: Benefit Equals Leader

Fascist governance depended not only on coercion or spectacle, but on conditioning sustained over time. The regime worked systematically to train citizens to associate material benefit, order, and opportunity with Mussolini himself rather than with impersonal state function. This association was not taught explicitly as doctrine or enforced through constant propaganda alone. It was learned implicitly through repetition embedded in everyday experience. Whenever a road opened, a pension expanded, a youth program launched, or a subsidy distributed, the regime ensured that Mussolini’s name, image, or voice accompanied the benefit. Public announcements, ceremonies, plaques, and press coverage framed improvement as personal intervention. Gratitude was redirected upward, bypassing institutions entirely and short-circuiting the logic of civic entitlement.

This conditioning altered political cognition. Citizens were not encouraged to ask how policies were funded, administered, or maintained. They were encouraged to ask who made them possible. Cause and effect were simplified into a single narrative chain: Mussolini acts, Italy benefits. This logic crowded out alternative explanations. Bureaucracy faded into the background, while personal authority became the visible source of all improvement. Even routine governance acquired an emotional dimension, framed as generosity rather than obligation.

The effectiveness of this strategy lay in its cumulative subtlety. Fascism did not need every citizen to be ideologically convinced or emotionally fervent. It needed them to internalize an association between stability and the leader’s presence. This association reshaped loyalty from a political stance into a practical instinct formed through experience. To criticize the regime was no longer simply to dispute policy or ideology. It was to risk being cast as ungrateful or destabilizing, someone who threatened the material order itself. Fear and gratitude merged, reinforcing obedience without constant enforcement and making dissent feel socially and materially dangerous.

Mussolini transformed governance into a personalized feedback loop. Benefits validated the leader, and the leader validated the benefits. Institutions were rendered secondary, even invisible, as citizens learned to interpret their material circumstances through a single human figure. The state no longer needed to justify itself through law or representation. It needed only to ensure that improvement appeared signed, and that gratitude had only one place to go.

Collapse without Memory: What Remained after Mussolini

The fall of Mussolini was abrupt, public, and deeply destabilizing. Once military defeat exposed the limits of fascist spectacle, the regime unraveled with remarkable speed. The leader who had been presented as omnipresent vanished almost overnight, and with him went the coherence of the system he had signed into existence. What had appeared durable because it was everywhere proved brittle because it depended on a single name. The collapse revealed how little institutional memory had been allowed to form beneath the surface of saturation.

Unlike regimes that embed authority in law or routine, fascist Italy left few structures capable of operating independently of the leader’s presence. Ministries existed, but they lacked autonomous legitimacy and initiative. Courts functioned, but they had been trained to defer rather than to arbitrate. Administrative systems remained in place, but years of personal override had stripped them of confidence and authority. When Mussolini disappeared, these institutions did not step forward to stabilize governance or articulate continuity. They hesitated, fractured internally, or were rapidly repurposed by occupying powers and successor regimes. The state had been signed, not structured, leaving little capacity for self-direction once the signature was removed.

This absence of institutional memory shaped postwar reckoning. Fascism could be disowned by isolating blame in the figure of Benito Mussolini himself. Streets were renamed back, symbols removed, portraits taken down, and slogans erased. The ease of this erasure reflected how little depth fascist legitimacy had achieved beyond its surface. What had been learned visually could be unlearned visually. There was no durable procedural core to dismantle, only imagery to remove.

The rapid disintegration also exposed the weakness of governance built on personal credit. Public works continued to exist physically, but their political meaning evaporated once the signature was gone. Roads still carried traffic, buildings still stood, and reclaimed land continued to be farmed, but these material remnants no longer conveyed legitimacy or gratitude. Without the leader’s name attached, abundance lost its narrative frame. Fascism had taught citizens who to thank, not how governance worked or why institutions mattered. When that person vanished, so did the story that linked benefit to authority, leaving infrastructure without explanation and governance without meaning.

Mussolini’s regime collapsed not only militarily or politically, but mnemonically. It left behind ruins without inheritance, symbols without continuity, and institutions without confidence. The state that had been branded so aggressively proved unable to remember itself without its author. Fascist eponymy produced intensity without endurance, visibility without durability. When the signature was erased, there was little left to claim, defend, or restore.

Conclusion: When the State Becomes a Signature, Not a System

Fascist Italy demonstrates the central paradox of hyper-visible power. By attaching governance so completely to a single name, Mussolini created a regime that felt omnipresent, decisive, and materially productive in the short term. The state appeared energetic because the leader appeared everywhere, signing action, movement, and improvement into existence. Visibility substituted for trust, repetition for legitimacy. Yet this saturation concealed a fundamental weakness. Institutions were never allowed to develop independent authority, procedural legitimacy, or durable memory. They existed to display obedience, not to generate continuity. Power was performed constantly, but it was rarely transferred, shared, or stabilized beyond the body that embodied it.

This form of governance proved effective only so long as the signature remained legible and intact. As long as Mussolini could be seen, named, photographed, praised, and credited, the system functioned with remarkable speed and coherence. The moment that visibility collapsed under military defeat and political reversal, the regime had nothing to fall back on. There was no neutral legal framework capable of commanding loyalty on its own terms, no trusted bureaucracy prepared to absorb authority, and no institutional memory strong enough to survive the disappearance of its author. What had looked like strength revealed itself as dependence. The state had been personalized so thoroughly that it could not endure impersonality.

The fascist experiment exposes the cost of branding abundance while hollowing institutions. Public works, renamed spaces, and visible benefits produced gratitude without resilience. Citizens were trained to associate governance with a person rather than with structures. When that person vanished, meaning evaporated. The speed with which fascist symbols were erased reflected not moral clarity alone, but the shallowness of the regime’s institutional roots. Memory had been organized around image, not around practice.

Mussolini offers a warning rather than a model. A state that becomes a signature may command attention, obedience, and even affection, but it cannot endure beyond its author. Systems survive because they teach citizens how governance works without asking who to thank. Fascist Italy taught Italians who to thank, and nothing more. When the signature disappeared, the state itself had to be rebuilt almost from scratch.

Bibliography

- Bosworth, R. J. B. Mussolini. London: Arnold, 2002.

- —-. Mussolini’s Italy. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Corner, Paul. The Fascist Party and Popular Opinion in Mussolini’s Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- —-. Popular Opinion in Totalitarian Regimes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Gentile, Emilio. The Origins of Fascist Ideology. New York: Enigma Books, 2005.

- —-. Politics as Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- —-. The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Glad, Betty. “Why Tyrants Go Too Far: Malignant Narcissism and Absolute Power.” Political Psychology 23:1 (2002), 1-37.

- Graber, Naomi. “Do You Hear the People Sing? Theater and Theatricality in the Trump Campaign.” American Music 35:4 (2017), 435-445.

- Kallis, Aristotle. Fascist Ideology. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Kogan, Norman. “The Origins of Italian Fascism.” Polity 2:1 (1969), 100-105.

- Lyttelton, Adrian. The Seizure of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Mras, George P. “Italian Fascist Architecture: Theory and Image.” Art Journal 21:1 (1961), 7-12.

- Neumann, Dietrich. “A Skyscraper for Mussolini.” AA Files 68 (2014), 141-153.

- Paxton, Robert O. The Anatomy of Fascism. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.09.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.