Because of the work of Linnaeus and others, entire populations were positioned as less rational, less capable, and less deserving of autonomy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Description becomes Judgment

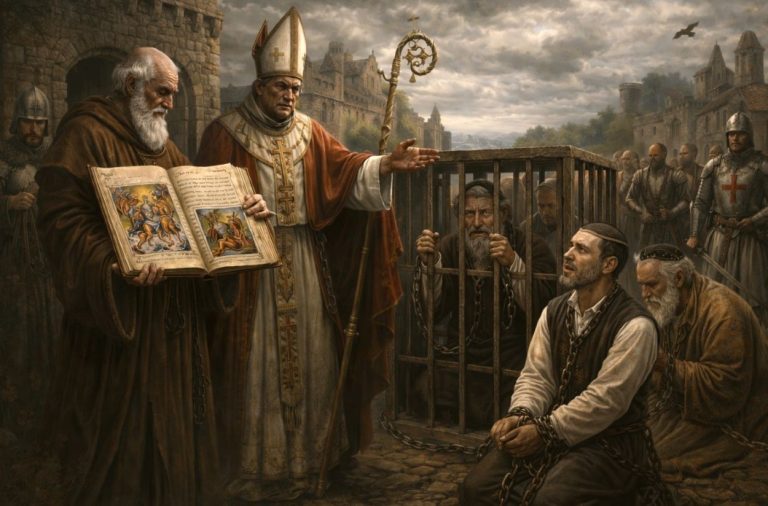

The Enlightenment promised a new way of knowing the world, grounded in observation, classification, and empirical description. Nature was to be ordered through reason rather than revelation, measured rather than interpreted through theology or inherited authority. This shift carried with it a powerful claim to neutrality. To describe was not to judge, but simply to record what was already there. Yet this transformation did not eliminate hierarchy. It reorganized it. In the eighteenth century, dehumanization did not vanish with the decline of overtly religious cosmology. It was reconstituted within scientific systems that treated difference as data and inequality as fact. Description, presented as dispassionate and objective, quietly acquired the force of judgment, often without acknowledging that it had done so.

Enlightenment race science transformed moral hierarchy into empirical observation by embedding it within systems of classification. Rather than denouncing certain peoples as sinful, barbaric, or damned, naturalists described them as measurable varieties of the human species. These descriptions carried with them assumptions about temperament, capacity, and moral character, even as they claimed to be value free. Hierarchy no longer required justification through scripture or tradition. It appeared instead as the outcome of careful study, the visible arrangement of nature itself.

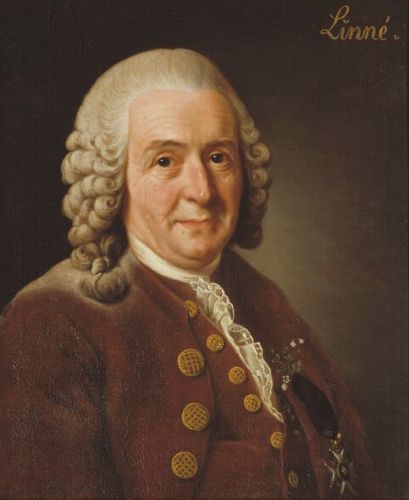

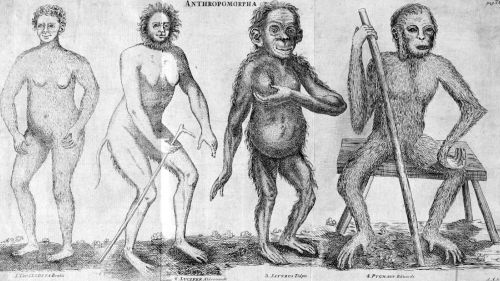

Carl Linnaeus, whose taxonomic system formalized the classification of humans within the same conceptual framework used to order plants and animals, is at the center of this transformation. In Systema Naturae, Linnaeus divided humanity into racialized categories, each associated not only with physical traits but with behavioral, emotional, and moral characteristics. These distinctions were presented as observations rather than evaluations, as if they merely recorded differences rather than producing them. Yet by placing human groups into a ranked natural order, Linnaeus converted political, cultural, and moral judgments into biological description. Taxonomy here did not simply name difference. It stabilized it, naturalized it, and insulated it from ethical scrutiny by embedding it within the authority of science itself.

The significance of this shift lies in its authority. Enlightenment race science was not fringe speculation or popular superstition. It was taught in universities, circulated among educated elites, and cited by administrators and imperial officials. Its claims carried the legitimacy of objectivity and the prestige of scientific reason. Racism, in this context, wore the mask of neutrality. By treating hierarchy as data, Enlightenment thinkers created a form of dehumanization that did not announce itself as hatred. It presented itself as knowledge, and in doing so, made domination appear not only rational but inevitable.

Linnaeus’s Taxonomic Imagination: Ordering Nature, Ordering Humanity

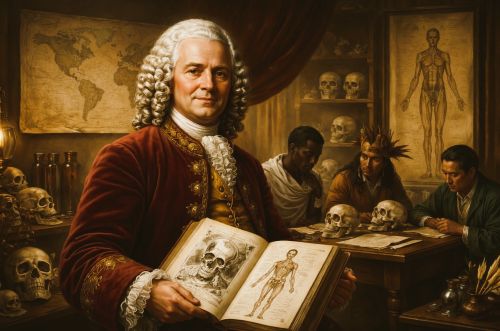

Carl Linnaeus’s scientific project was animated by a profound desire to impose order on the natural world through systematic classification. In the early eighteenth century, European naturalists confronted what they perceived as an overwhelming abundance of plants, animals, and human variation that resisted easy comprehension. Linnaeus responded by developing a universal taxonomic system that promised clarity, stability, and comparability across regions and species. Through standardized naming and hierarchical grouping, nature could be rendered legible to reason. This was not merely a technical or methodological achievement. It carried with it an epistemological claim about the world itself: that creation was inherently ordered that this order could be discovered through careful observation, and that those who mastered classification possessed a privileged form of knowledge about reality.

In Systema Naturae, Linnaeus extended this classificatory impulse to humanity itself in a way that was both innovative and deeply consequential. Humans were not treated as a category apart from nature but were placed squarely within the animal kingdom, classified alongside other mammals according to shared anatomical traits. On the surface, this move appeared radically egalitarian, collapsing theological distinctions between humans and animals in favor of biological continuity. Yet this apparent leveling masked a new and more subtle hierarchy. By subjecting humans to taxonomic division, Linnaeus made it possible to order humanity internally, sorting populations through the same descriptive logic applied to flora and fauna. Human difference was no longer interpreted primarily through culture, history, or politics. It became a problem of natural classification.

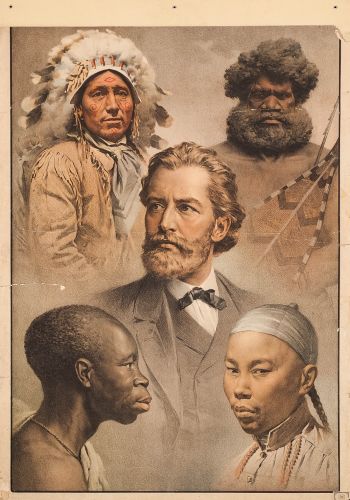

Linnaeus divided humans into distinct varieties, often labeled according to continental geography. These categories were defined not only by physical characteristics such as skin color and bodily form, but by temperament, behavior, and disposition. Europeans were described as inventive and governed by laws, while other groups were characterized as impulsive, lazy, or governed by custom. Although framed as observations, these descriptors carried normative weight. They translated cultural stereotypes and colonial assumptions into the language of natural history, presenting social judgments as empirical facts.

The taxonomic imagination at work here did not merely describe difference. It fixed difference in place and endowed it with durability. Once human variation was rendered as a stable set of categories within nature, it became resistant to challenge and revision. Political inequality could now be explained as the consequence of biological variation rather than historical circumstance, conquest, or power relations. By embedding moral and behavioral traits within racial categories, Linnaeus ensured that hierarchy appeared to precede politics itself. Inequality was no longer something societies actively produced and maintained. It was something nature revealed and science merely recorded.

What made this system especially powerful was its tone. Linnaeus did not write as a polemicist or moral theorist. His prose was spare, classificatory, and technical. The absence of overt judgment enhanced the credibility of his claims. Description functioned as a moral alibi. By presenting hierarchy as a matter of record rather than opinion, Linnaeus’s taxonomy shielded itself from ethical critique. To dispute the hierarchy was to dispute nature itself, or the scientific method used to apprehend it.

The result was a conceptual framework in which domination could be understood as alignment with reality rather than the exercise of power. Linnaeus did not need to argue for colonial rule, enslavement, or European superiority explicitly. His system supplied the categories through which such practices could later be rationalized. By ordering nature, he also ordered humanity, providing Enlightenment Europe with a scientific vocabulary that rendered hierarchy legible, stable, and seemingly inevitable.

From Bodies to Characters: When Biology Acquires Morality

Linnaeus’s racial categories did not remain confined to physical description. They quickly became vehicles for moral interpretation. In Systema Naturae, bodily traits were paired with assessments of temperament, behavior, and social capacity, collapsing the distinction between what a person was and how a person was said to act. Skin color, climate, and physiology were treated as indicators of inner character. What appeared as neutral observation acquired ethical content. Biology became a language through which morality was inferred rather than debated.

This shift rested on a broader Enlightenment assumption that nature produced not only physical form but disposition itself. Climate theory, humoral medicine, and environmental determinism all contributed to the belief that character could be read directly from the body, as if moral tendencies were environmentally inscribed into flesh. Linnaeus drew upon these currents to describe Europeans as rational, inventive, and governed by law, while portraying non-European groups as impulsive, indolent, emotional, or governed by custom. These descriptions were embedded in scientific prose rather than moral polemic, which made them appear observational rather than evaluative. Yet the effect was unmistakable. By presenting moral traits as natural tendencies shaped by biology and environment, Enlightenment science converted social hierarchy into an outcome of nature rather than history. Judgment entered not as condemnation, but as explanation.

The consequences of this move were profound and far-reaching. Once moral and behavioral traits were treated as biological facts, social inequality no longer required ethical justification or political defense. Differences in governance, education, labor, and political participation could be attributed to natural disposition rather than to coercion, exploitation, or exclusion. Hierarchy appeared as the rational arrangement of unequal capacities, not as the result of violence or domination. Europeans did not rule, in this framework, because they asserted superiority. They ruled because their biology allegedly equipped them for reason, discipline, foresight, and self-control. Others were governed because they were said to lack these capacities by nature, making subordination appear protective rather than oppressive.

This framework also foreclosed the possibility of moral transformation in a way that earlier religious hierarchies had not. Medieval theology, for all its exclusions, at least allowed for conversion, repentance, and spiritual change. Enlightenment race science offered no such escape. If character was biologically grounded, then education, conversion, or cultural adaptation could never fully overcome natural limitation. Improvement might be possible at the margins, but equality was structurally impossible. Moral destiny was written into the body itself. Difference became fixed, durable, and resistant to ethical challenge, reinforced by the authority of science rather than contested through moral argument.

When biology acquired morality in this way, dehumanization no longer required insult, demonization, or explicit comparison to animals. It operated instead through quiet inference. To describe a body was to imply a character. To record difference was to assign value. Racism became legible as data rather than belief, as knowledge rather than prejudice. This was the crucial transformation of Enlightenment race science: it allowed moral hierarchy to persist while claiming to have abandoned moral judgment altogether.

Humans, Apes, and the Edge of the Species

As Enlightenment naturalists extended classificatory logic, the boundary between human and animal became increasingly unstable, not because it was openly rejected, but because it was quietly reorganized. Linnaeus’s decision to place humans and apes in close proximity within the taxonomic order Primates appeared, on its surface, to be a restrained and methodologically consistent choice. Humans shared anatomical features with apes, and classification followed form. Yet this proximity carried consequences that far exceeded technical taxonomy. By situating humans alongside nonhuman animals within a single classificatory framework, Enlightenment science invited comparison where theology had once insisted on absolute separation. This continuity did not threaten European self-understanding so long as hierarchy could be preserved. The critical question was never whether humans were animals, but which humans were closest to the animal edge of the species.

Non-European peoples were repeatedly positioned as occupying ambiguous ground between full humanity and animality. Enlightenment thinkers speculated about gradations of rationality, self control, and moral development, often invoking comparisons to apes or so called primitive intermediates. These comparisons did not always take the form of explicit declarations. More often, they appeared as suggestions, measurements, or classificatory uncertainties that implied lesser humanity without stating it outright. Ambiguity itself became a tool. By leaving the boundary unresolved, race science could deny full human status while maintaining scientific plausibility.

This proximity to animality had significant political consequences. If some populations were understood as closer to animals in disposition or development, then domination could be framed as management rather than injustice. Enslavement, forced labor, and colonial rule could be rationalized as appropriate forms of supervision for beings deemed insufficiently rational for autonomy. Comparisons to apes stripped groups of moral standing without requiring overt denial of humanity. They existed in a liminal category, human enough to labor and obey, but not human enough to rule themselves or demand equal rights.

What made this logic particularly effective was its claim to restraint and moderation. Enlightenment thinkers often insisted that they were merely observing gradations within nature, not asserting superiority or inferiority in moral terms. This posture allowed them to disavow responsibility for the consequences of their classifications. Yet the gradations they described carried unmistakable political and ethical weight. By situating some humans at the edge of the species, race science provided a framework in which exploitation could be experienced as scientific necessity rather than cruelty or choice. Dehumanization here did not operate through slander, myth, or theological condemnation, but through classificatory uncertainty itself. At the edge of the species, humanity could be diminished, constrained, and governed without ever being explicitly denied, making domination appear careful, rational, and unavoidable.

Data for Empire: Race Science as Administrative Knowledge

Enlightenment race science did not remain confined to books, lectures, or philosophical debate. Its classificatory logic migrated outward into the administrative machinery of empire, where it became a practical tool of governance. Taxonomies developed in universities and learned societies were taken up by colonial officials, military planners, and legal administrators who required systems for managing populations at scale. Scientific classification offered a language that translated difference into order. By rendering human variation legible as data, race science allowed empire to govern through categories that appeared rational, neutral, and necessary.

Colonial administrations relied on racial classification to organize labor, territory, and law. Populations were sorted according to presumed capacity, temperament, and fitness, often using scientific terminology to justify unequal treatment. Certain groups were deemed naturally suited for hard labor, others for supervision, and others for exclusion altogether. These distinctions did not need to be argued morally. They were presented as empirical facts drawn from the authority of science. Administrative decisions appeared technical rather than political, masking coercion behind procedure.

Universities and scientific institutions played a crucial role in legitimizing this process and ensuring its durability. Race science was taught as part of natural history, medicine, anthropology, and emerging social sciences, producing graduates who carried classificatory assumptions directly into imperial service. Administrators, surveyors, physicians, and military officers could cite respected authorities, measurements, and taxonomic schemes to support policies of enslavement, segregation, land seizure, or differential legal status. This connection between scholarly knowledge and state power gave racial hierarchy a veneer of inevitability. Policy did not appear to originate in prejudice or interest, but in education and expertise. The authority of credentials replaced the need for overt justification, allowing domination to present itself as informed judgment rather than imposed will.

This administrative use of data also transformed violence. Coercive practices such as forced labor, population displacement, and collective punishment could be framed as rational management rather than oppression. When people were reduced to entries in classificatory systems, harm could be distributed impersonally across institutions. No single actor needed to intend cruelty. Responsibility dissolved into reports, censuses, regulations, and statistical summaries. Dehumanization here was not emotional or spectacular. It was procedural, embedded in routines that treated inequality as a logistical problem to be solved.

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, race science had become embedded in the everyday functioning of empire in ways that were difficult to disentangle. Data replaced theology as the primary justification for domination, offering a language that seemed modern, rational, and progressive. Classification enabled rule without constant recourse to visible force by making inequality appear administratively obvious and scientifically grounded. Empire could present itself not as violent conquest, but as orderly governance responding to natural difference. When dehumanization became data, domination no longer needed to declare itself. It could operate quietly, continuously, and with the confidence of objectivity.

Objectivity as Alibi: Why Enlightenment Racism Endured

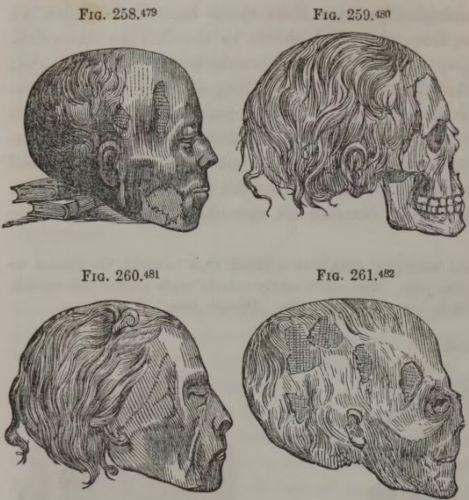

Enlightenment race science endured, influencing later physicians and naturalists such as Samuel George Morton, not because it was especially aggressive or rhetorically extreme but because it presented itself as restrained, careful, and impartial. Its authority rested on the claim that it merely described the world as it was, free from passion, theology, or interest. By framing hierarchy as observation rather than assertion, scientific racism insulated itself from moral challenge. To disagree was not to contest injustice, but to misunderstand nature or reject reason. Objectivity functioned as an alibi, allowing dehumanization to proceed without appearing to choose cruelty.

This posture drew strength from the Enlightenment’s broader epistemic ideals, which elevated detachment and self-discipline as intellectual virtues. Objectivity was increasingly defined as the ability to suppress emotion, sympathy, and moral intuition in favor of measurement, comparison, and classification. The good observer was one who did not feel too much, who did not intervene, who recorded rather than reacted. Within this framework, moral concern itself could be recast as distortion. Sympathy threatened accuracy. Ethical judgment threatened neutrality. Race science benefited enormously from this inversion. The colder and more technical its language, the more authoritative it appeared. The absence of overt animus did not weaken its claims. It strengthened them, allowing hierarchy to masquerade as restraint rather than domination.

Scientific racism also endured because it distributed responsibility across systems rather than concentrating it in individuals. Linnaean classification did not require any single actor to advocate enslavement or domination explicitly. It supplied categories that others could apply. Administrators, physicians, educators, and officials could act within the system while disavowing moral agency. They were not choosing hierarchy. They were applying knowledge. This diffusion of responsibility made racism resilient, difficult to confront, and resistant to reform.

Another source of endurance lay in the adaptability of data. Racial categories could be refined, subdivided, and recalibrated without abandoning the underlying hierarchy. New measurements, new instruments, and new terminologies could be introduced while preserving the same moral ordering. When challenged, race science did not collapse. It updated. Objectivity provided flexibility without accountability, allowing the system to evolve while maintaining its core assumptions about difference and capacity.

The appeal to objectivity also shielded race science from comparison with earlier forms of hierarchy in ways that made it appear progressive rather than continuous. By rejecting overt theological, mythic, or openly prejudicial justifications, Enlightenment thinkers could present their work as a moral advance over religious persecution or aristocratic inheritance. Scientific racism appeared more humane precisely because it claimed neutrality and universality. Yet this claim obscured the deeper continuity. What had changed was not the function of hierarchy, but its vocabulary. Domination no longer required divine sanction, scripture, or tradition. It required data, measurement, and the authority of reason. This shift made hierarchy harder to see, not less powerful.

Enlightenment racism endured because it taught societies to mistake description for destiny and classification for truth. When inequality is framed as fact rather than choice, moral outrage loses its footing. Objectivity becomes a way of not seeing harm, of translating suffering into tables, charts, and comparative categories. Violence does not disappear under such systems. It is reorganized, dispersed, and rendered impersonal. In this sense, scientific racism did not fail in spite of its restraint. It succeeded because of it. By wearing the mask of objectivity, dehumanization could persist long after openly racist doctrines were challenged, precisely because it no longer looked like racism at all.

Conclusion: When Dehumanization Calls Itself Knowledge

Enlightenment race science did not invent hierarchy, but it perfected a new way of disguising it. By translating moral judgment into classification and domination into description, figures like Linnaeus helped inaugurate a system in which inequality appeared as the natural order of things rather than as the product of human decision. The power of this transformation lay not in its hostility, but in its restraint. Dehumanization no longer needed to shout. It only needed to record. Once hierarchy could be read as data, it no longer required defense. It could present itself as truth.

What distinguishes this moment from earlier regimes of exclusion is not the severity of its consequences, but the sophistication of its justification and its insulation from ethical critique. Medieval theology and early modern prejudice named enemies and condemned them openly, relying on visible moral boundaries and explicit denunciation. Enlightenment science, by contrast, claimed to have moved beyond such passions. It replaced condemnation with categorization and hatred with measurement, presenting hierarchy as the outcome of observation rather than will. Yet the outcome was the same. Entire populations were positioned as less rational, less capable, and less deserving of autonomy. The language had changed, but the structure of domination remained intact, now fortified by the authority of objectivity and the prestige of reason itself.

This history matters because it exposes the ethical danger embedded in claims of neutrality. When knowledge presents itself as merely descriptive, it can obscure the values that shape what is observed, how it is classified, and why it matters. Enlightenment race science demonstrates how easily power can hide behind method, and how moral responsibility can be dissolved into procedure. Once suffering is rendered as a statistical consequence of natural difference, outrage appears irrational and resistance appears ignorant. Knowledge becomes a shield against accountability.

To recognize this is not to reject science or classification, but to insist on their moral scrutiny and historical context. The lesson of Enlightenment race science is not that knowledge is inherently corrupt, but that it is never innocent or detached from power. When dehumanization calls itself knowledge, it gains durability, respectability, and reach. It no longer looks like violence. It looks like reason, professionalism, and good method. The task of historical critique is to make that transformation visible again, to recover the human cost hidden behind the language of objectivity, and to remember that what is described as natural has almost always been chosen, defended, and enforced by human hands.

Bibliography

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Modernity and the Holocaust. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich. On the Natural Varieties of Mankind. Translated by Thomas Bendyshe. London, 1865.

- Charmantier, Isabelle. “Carl Linnaeus and the Visual Representation of Nature.” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 41:4 (2011), 365-404.

- Cohn, Bernard. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books, 2007.

- Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi. Race and the Enlightenment. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

- Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage Books, 1966.

- —-. Society Must Be Defended. New York: Picador, 1976.

- Gissis, Snait B. “Visualizing ‘Race’ in the Eighteenth Century.” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 41:1 (2011), 41-103.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. The Mismeasure of Man. New York: W. W. Norton, 1980.

- Hacking, Ian. The Taming of Chance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Kevles, Daniel J. “The History of Eugenics.” Issues in Science and Technology 32:3 (2016), 45-50.

- Koerner, Lisbet. Linnaeus: Nature and Nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Linnaeus, Carl. Systema Naturae. 10th ed. Stockholm, 1758.

- Nelson, William Max. “Making Men: Enlightenment Ideas of Racial Engineering.” The American Historical Review 115:5 (2010), 1364-1394.

- Outram, Dorinda. The Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Paris, LaRose T. Being Apart: Theoretical and Existential Resistance in Africana Literature. Richmond: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

- Ricklefs, Robert E. “Naturalists, Natural History, and the Nature of Biological Diversity.” The American Naturalist 179:4 (2012), 423-435.

- Ritvo, Harriet. The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Stafford, Barbara Maria. Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Wolff, Larry. Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.10.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.