This is not a pathology of modern media or contemporary polarization alone. It is a structural temptation wherever authority becomes insulated from accountability.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Disagreement Becomes a Diagnosis

Political disagreement has rarely been treated as a neutral act. Challenges to authority have been recast throughout history not merely as errors of judgment or differences of principle, but as signs of moral failure, irrationality, or inner disorder. This maneuver does more than insult opponents. It shifts the ground of political conflict itself. Once dissent is framed as a symptom rather than an argument, it no longer requires rebuttal. It requires dismissal. Power is relieved of the burden of persuasion and replaces debate with diagnosis.

What follows examines that maneuver at one of its earliest and most revealing points of articulation: the reign of Caligula. Under his rule, opposition within the Roman elite was not engaged as political resistance but was mocked, derided, and neutralized as evidence of instability or defective reason. Senators who questioned imperial behavior were portrayed as incapable of rational thought, unfit for serious consideration, or dangerously disconnected from reality. Such portrayals functioned to collapse the distinction between dissent and disorder, allowing imperial authority to treat criticism as self-discrediting. This was not casual cruelty or the byproduct of a volatile personality. It was a governing logic that turned elite political culture against itself. Loyalty was equated with sanity. Skepticism became pathology. The more insistently a senator appealed to precedent, tradition, or reasoned restraint, the more easily that appeal could be recoded as obsession, fixation, or delusion.

To pathologize opposition is to redefine the boundaries of legitimate speech. The move converts disagreement into incapacity and transforms political hierarchy into a hierarchy of mental fitness. In such a system, authority does not merely govern actions but claims jurisdiction over reality itself, deciding whose perceptions count as rational and whose must be dismissed as disordered. The consequences are profound. Once power claims the right to define sanity, it also claims the right to exclude certain voices from the political community altogether.

Caligula’s Rome offers a concentrated case study of this dynamic, not because it was unique, but because it was unusually explicit. The early imperial system already constrained dissent through custom, fear, and informal coercion, but Caligula sharpened those constraints into a cultural weapon that worked preemptively. Opposition did not need to be punished if it could be rendered unintelligible. By examining how disagreement was reframed as madness under his reign, this traces a recurring political pattern that extends far beyond antiquity. When power redescribes disagreement as a psychological flaw, it does not simply silence critics through force or law. It teaches society to distrust them, to doubt their motives and perceptions, and to treat their exclusion as a matter of prudence rather than repression. In doing so, it reshapes the very meaning of political participation, redefining citizenship itself as a test of mental conformity.

Political Culture of the Early Principate

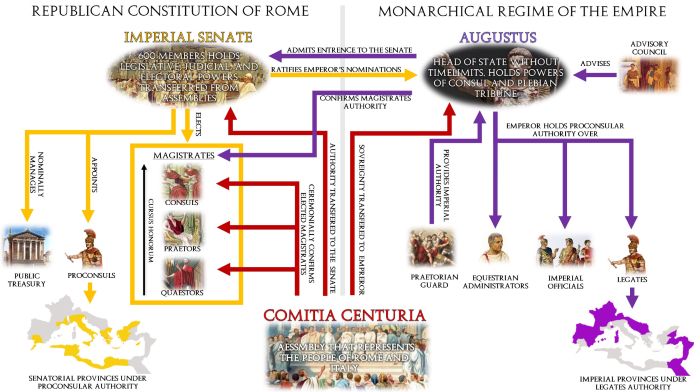

The political culture inherited by the early Roman emperors was shaped by contradiction. The Augustan settlement preserved the outward forms of republican governance while hollowing out their operative power. Magistracies, senatorial debate, and traditional offices continued to exist, complete with ritual, language, and expectation, but decision-making authority increasingly flowed through the person of the princeps. This arrangement depended not only on law but on performance and shared illusion. The emperor was expected to rule while appearing not to rule, to command while affirming the dignity of institutions that no longer constrained him. Stability rested on a collective agreement to treat diminished forms as if they retained their former substance, an agreement that could fracture quickly under strain.

Elite political speech was already precarious within this system. Senators were trained in rhetoric, moral reasoning, and historical exempla, yet their traditional tools had diminishing effect as the balance of power shifted. Appeals to precedent or constitutional principle could be interpreted as pedantry, nostalgia, or veiled challenge rather than constructive counsel. The space between loyalty and resistance narrowed as imperial authority became more personalized and less procedural. What mattered was not merely what was said, but how it was heard by the ruler, his advisors, and the broader court culture. Disagreement increasingly carried interpretive risk, and meaning itself became unstable, subject to the moods and suspicions of those closest to power.

Roman cultural ideals further sharpened this vulnerability. Elite masculinity was bound to concepts of rational self-control, emotional restraint, and moral steadiness. To lose composure or to appear fixated on a single grievance was to invite suspicion. Madness in Roman thought was not primarily a medical category but a moral and civic one. It signified excess, imbalance, and failure of self-governance. A man who could not govern himself, Romans believed, could not be trusted to advise or govern others.

This moralized understanding of rationality made dissent easy to reframe. Persistent criticism could be cast as obsession. Moral protest could be recoded as irrational indignation. Even silence, if interpreted as sulking or withdrawal, could be read as emotional instability. The political culture of the early Principate created a feedback loop in which caution bred further suspicion. Those who spoke risked being labeled unreasonable. Those who refrained risked appearing sullen or mentally withdrawn from civic life.

The reign of Augustus had relied heavily on senatorial cooperation, even as it limited senatorial power in practice. His authority rested on consensus, cultivated image, and deliberate restraint, reinforced by careful attention to elite sensibilities. Augustus understood that the appearance of rational dialogue mattered as much as its substance. Yet this model depended entirely on a ruler willing to maintain the fiction of shared governance. Once that restraint weakened under later emperors, the same cultural norms that had supported stability could be inverted. Ideals of rationality, moderation, and emotional discipline could be turned into standards against which dissenters were measured and found wanting.

By the time Caligula came to power, the political culture of the Principate was primed for psychological delegitimization. Formal opposition was already constrained by fear, precedent, and institutional inertia. Informal dissent depended on tone, timing, and personal favor rather than on principle or office. In this environment, the pathologizing of opposition did not emerge suddenly or aberrantly. It evolved naturally from a system that conflated political disagreement with moral character and rational capacity. The early Principate supplied the cultural infrastructure that made Caligula’s tactics legible, effective, and difficult to resist, long before they were deployed with open contempt.

Caligula’s Reign and the Recasting of Opposition

When Caligula ascended to the imperial throne, he inherited not only extraordinary authority but a political culture already strained by ambiguity and fear. Early enthusiasm for his rule quickly gave way to confusion as his behavior defied elite expectations of restraint, continuity, and decorum. What distinguished Caligula was not merely cruelty or extravagance, but the way he responded to resistance. Opposition was not answered through argument, accommodation, or even consistent repression. Instead, it was transformed into a spectacle of irrationality, with dissenters portrayed as mentally unbalanced rather than politically opposed.

Caligula’s interactions with the Senate illustrate this shift with particular clarity. Senators who questioned his actions or resisted his demands were subjected to ridicule rather than rebuttal. Their objections were dismissed as the ramblings of men who had lost touch with reality, who misunderstood their place in the new order, or who were constitutionally incapable of sound judgment. Public mockery served as a warning not only to its immediate targets but to the entire political class. To speak critically was not to risk losing an argument or suffering principled defeat, but to risk being reclassified as unserious, unstable, or delusional. In this environment, disagreement itself became evidence of deficiency, and the very act of questioning imperial behavior was reframed as proof of irrationality.

Humiliation was central to this strategy and operated as a form of political pedagogy. Caligula routinely staged encounters designed to strip senators of dignity, forcing them into roles that undermined their claims to rational authority. By compelling elite men to perform submission, endure arbitrary commands, or participate in absurd rituals, he blurred the line between political compliance and psychological collapse. These episodes were not random cruelty. They functioned as lessons about reality and power. If those who opposed the emperor could be made to appear ridiculous or emotionally unmoored, then their arguments need not be addressed at all. Power was exercised not only through punishment, but through the public redefinition of who counted as a credible political actor and who did not.

This recasting of opposition relied on inversion. Traditional Roman virtues such as seriousness, constancy, and moral gravity were turned against those who displayed them. A senator who clung to precedent could be mocked as inflexible or obsessive. One who protested moral transgression could be dismissed as hysterical or overwrought. Rationality itself became suspect when it conflicted with imperial will. Caligula positioned himself as the arbiter of reason, while portraying his critics as incapable of understanding the reality he alone defined.

The result was a political environment in which loyalty functioned as a diagnostic category rather than a mere political stance. Sanity was demonstrated through acquiescence, adaptability, and silence, while consistency and principle became liabilities. Skepticism signaled disorder, and persistence marked one as mentally unfit for public life. This framework allowed Caligula to neutralize opposition without the continuous use of formal trials or legal justification. By redefining dissent as madness, he rendered resistance not merely dangerous, but unintelligible. The emperor did not need to defeat his opponents through argument or law. He only needed to deny that they were thinking clearly enough to matter.

Madness as Delegitimization, Not Diagnosis

Accusations of madness under Caligula were not attempts to identify illness or incapacity in any meaningful medical sense. They functioned instead as acts of political erasure, aimed at stripping opponents of credibility rather than understanding their condition. Roman society possessed no institutional framework for psychiatric care, nor did imperial authority display interest in treatment, rehabilitation, or protection of the allegedly unwell. To be labeled irrational was not to be removed for care but to be expelled from seriousness. Madness operated as a verdict, not a condition, and its purpose was exclusion rather than explanation. It marked the boundary between voices that counted and those that could be ignored without consequence.

This distinction matters because it clarifies intent and reveals the logic at work. If dissenters had been understood as genuinely unwell, one might expect responses oriented toward guardianship, restraint from public duties, or some form of protective withdrawal. Instead, the charge of irrationality was deployed selectively, situationally, and rhetorically. It appeared precisely where disagreement threatened imperial authority or embarrassed the emperor. Senators were not consistently described as mad across contexts or behaviors. They were described as mad when they resisted, persisted, or refused to adapt. The accusation followed opposition, not pathology. Madness was not discovered through observation. It was assigned through conflict.

By recoding opposition as psychological defect, imperial power eliminated the need for substantive engagement. Arguments grounded in law, tradition, or moral reasoning no longer required rebuttal if the speaker could be dismissed as incapable of reason. This maneuver transformed political conflict into a question of capacity. The issue was no longer whether a criticism was valid, coherent, or historically grounded, but whether the critic was mentally fit to offer one at all. Authority shifted from contesting ideas to adjudicating sanity, a far more asymmetric and unanswerable form of power.

This strategy also altered the legal and moral status of opposition in subtle but consequential ways. In Roman law, individuals deemed incapable of rational judgment could be denied full civic participation or placed under supervision. By associating dissent with irrationality, imperial rhetoric drew on these assumptions without invoking formal legal processes. No declaration of incapacity was required. No trial needed to be staged. The result was a gray zone in which critics were neither openly prosecuted nor openly tolerated. They were rendered marginal, their words drained of force by the suggestion that they emerged from a defective mind rather than a reasoned political position.

Madness functioned as a political solvent. It dissolved the legitimacy of opposition without the visible costs of repression. There were no trials to justify, no verdicts to defend, no martyrs to create. Instead, there was only the quiet insistence that disagreement itself signaled imbalance. Once accepted, this logic disciplined not only those accused, but those who observed the accusations. It taught the political community that to resist too clearly, too persistently, or too coherently was to risk being recoded as irrational and unworthy of response.

From Roman Court to Political Pattern

What occurred under Caligula did not end with his assassination, nor was it confined to the peculiarities of his temperament. The recasting of opposition as madness revealed a political logic that outlived the Julio-Claudian court and resurfaced wherever power sought insulation from critique. Rome provides an early, sharply illuminated instance of a broader pattern: when authority becomes insecure or unaccountable, it often abandons persuasion in favor of disqualification. Dissent is no longer answered. It is explained away as irrational, unstable, or emotionally defective.

This pattern is not dependent on a specific constitutional form, nor is it limited to overtly autocratic regimes. Monarchies, empires, and ostensibly representative systems have all employed psychological delegitimization when institutional checks weaken or become performative. The tactic thrives in environments where power is personalized and where loyalty is read as a measure of character rather than agreement. By framing opposition as mental failure, rulers avoid the risks inherent in open confrontation. They do not have to prove critics wrong, expose their own inconsistencies, or justify controversial decisions. They only have to suggest that critics are unwell, obsessive, or detached from reality, thereby shifting attention away from substance and toward supposed incapacity.

The appeal of this strategy lies in its efficiency and deniability. Unlike overt repression, which generates visible victims and invites moral scrutiny, pathologization operates quietly and often appears humane. It recruits social norms, professional authority, and cultural stigma to do the work of silencing. Once a critic is framed as irrational, others need not fear punishment to withdraw their support. They distance themselves instinctively, wary of association and reputational contamination. The political community polices itself, internalizing the lesson that credibility depends not on truthfulness or principle, but on psychological conformity and emotional tone.

This logic reshapes institutions themselves. Advisory bodies become populated not by those most capable of critique, but by those most adept at appearing reasonable under prevailing definitions of sanity. Administrative systems learn to reward emotional compliance and punish principled persistence. What begins as a rhetorical tactic hardens into a structural filter, sorting voices before they ever reach formal arenas of debate. Opposition survives, but only in muted, fragmented forms.

Rome under Caligula is not an aberration but a warning case with enduring relevance. It exposes how easily political disagreement can be reframed as incapacity once authority claims the power to define rationality. The Roman court provided the stage, but the script has been reused repeatedly across history, adapted to new languages and institutions. Whenever disagreement is treated as evidence of defect rather than difference, the lesson of Caligula’s reign reappears with clarity: power has shifted from governing actions to governing minds, and from answering critics to diagnosing them.

Modern Echoes: Pathology in Contemporary Politics

The logic visible in Rome during Caligula’s reign did not disappear with the fall of the empire. It reemerged, adapted to new vocabularies and institutions, wherever political disagreement threatened entrenched authority. In modern politics, the language of madness has often been replaced by a more clinical register, but the function remains the same. Opposition is not merely wrong or misguided. It is framed as unhinged, delusional, irrational, or psychologically compromised. The target is not the argument but the capacity of the speaker to argue at all.

Contemporary political discourse is saturated with this mode of delegitimization. Critics are dismissed as suffering from “derangement,” “paranoia,” or emotional instability, labels that carry immediate social stigma and foreclose engagement. Policy disagreements are redescribed as symptoms of obsession, resentment, or projection rather than reasoned dissent. This language appears across ideological boundaries and media ecosystems, often masquerading as wit or diagnostic insight. Its structural role, however, is consistent. By casting opponents as psychologically impaired, political actors avoid engaging with substance while presenting themselves as the guardians of normalcy, balance, and common sense. The effect is not to win arguments, but to disqualify arguers.

What distinguishes the modern context is the presence of professionalized psychological language. Terms borrowed from psychiatry and behavioral science carry an aura of expertise and neutrality. When deployed politically, they cloak power in the language of care and diagnosis. The suggestion that an opponent is unstable can be framed as concern rather than hostility. This allows delegitimization to masquerade as responsibility, transforming political exclusion into an act of supposed prudence or protection.

Media ecosystems amplify this effect. Repetition converts insinuation into assumption, and assumption into background truth. Once a figure or movement is persistently associated with irrationality, its claims are filtered through that association regardless of content or evidence. Interviews, commentary, and analysis focus less on what is said than on what the speech supposedly reveals about temperament, emotional regulation, or mental state. Visual framing, headline language, and selective quotation reinforce these cues. As in Rome, credibility becomes contingent not on coherence or proof, but on perceived psychological fitness as determined by hostile narrators.

The consequences for democratic culture are corrosive and cumulative. Democratic systems rely on the premise that disagreement is legitimate and that political opponents are rational agents capable of persuasion and compromise. When dissent is pathologized, that premise erodes incrementally. Opponents are no longer fellow citizens with different views, but risks to be managed, contained, or dismissed. Good-faith disagreement becomes indistinguishable from deviance. Political participation narrows as individuals learn to self-censor, soften claims, or withdraw entirely to avoid stigmatization. Pluralism survives in form, but not in spirit.

This modern pattern does not require authoritarian institutions to function. It operates comfortably within formally democratic frameworks precisely because it bypasses law. No censorship statutes are needed when credibility can be quietly withdrawn. No prosecutions are required when arguments can be dismissed as symptoms. The lesson that emerges, echoing the Roman case, is that the pathologizing of opposition remains one of the most effective tools of power. It silences without forbidding, excludes without condemning, and disciplines political culture by redefining sanity as agreement.

The presidency of Donald Trump provides a contemporary illustration of this dynamic operating in both directions. Critics of Trump have frequently framed his rhetoric, behavior, and decision-making as evidence of psychological instability, treating political objection as self-evident diagnosis rather than argument. At the same time, Trump himself has repeatedly characterized opponents, journalists, and institutional critics as unhinged, deranged, or incapable of clear thought. In both cases, political conflict is displaced into questions of mental fitness. Substantive disagreements over law, policy, or democratic norms are subordinated to narratives about sanity and pathology. The result is a political culture in which disagreement is no longer contested on shared grounds, but medicalized, personalized, and removed from the realm of mutual persuasion altogether.

Why Pathologizing Dissent Is So Effective

The enduring effectiveness of pathologizing dissent lies in its ability to neutralize opposition without invoking overt force. Unlike censorship or imprisonment, which visibly mark power as coercive, psychological delegitimization appears subtle, even reasonable. It reframes conflict as concern and exclusion as prudence. By suggesting that critics are irrational rather than wrong, authority avoids the appearance of repression while achieving the same outcome. Silence follows not because dissent is forbidden, but because it is made socially hazardous.

This strategy also exploits deep cultural anxieties about credibility and belonging. In most political communities, to be taken seriously is to be recognized as rational, composed, and emotionally proportionate. The accusation of instability threatens that recognition at its core, striking at reputation rather than argument. Once attached, it is difficult to dislodge, because any attempt at defense risks reinforcing the premise that sanity is in question. The dissenter is forced into a double bind, compelled to demonstrate emotional moderation while simultaneously challenging the power that defined them as unstable. Political energy is diverted away from substance and toward self-justification. Power controls the terms of engagement before engagement even begins.

Pathologization is especially potent because it recruits others to enforce it. Colleagues, allies, and institutions often distance themselves from those labeled irrational, not out of conviction but out of caution. Association carries risk in environments where credibility is fragile and stigma travels quickly. This produces a chilling effect that extends far beyond the original target. Observers learn which forms of disagreement invite delegitimization and which remain safe. Communities internalize these boundaries, regulating speech and behavior without direct intervention from authority. What begins as a tactic becomes a norm.

Pathologizing dissent reshapes political memory itself, with consequences that outlast any individual conflict. Once opposition is coded as madness, its arguments are not preserved, debated, or integrated into institutional learning. They are archived as symptoms rather than remembered as positions. Later narratives treat resistance as aberration instead of warning, excess instead of critique. This erasure benefits power in the long term, insulating it not only from present challenge but from retrospective judgment. What remains is a narrowed political record in which dissent appears incoherent or marginal by definition. In this way, the pathologizing of dissent does not merely silence voices in the moment. It alters the conditions under which dissent can be recognized, transmitted, and understood at all.

Conclusion: Sanity, Power, and the Fragility of Disagreement

The history traced here reveals a persistent and consequential maneuver in the exercise of power: the recasting of disagreement as psychological defect. From the court of Caligula to modern political discourse, the pathologizing of opposition has functioned as a means of silencing without argument and excluding without law. It replaces persuasion with diagnosis and turns political conflict into a question of fitness rather than legitimacy. Once dissent is treated as evidence of instability, authority is freed from the obligation to answer it, and political power shifts from engaging claims to managing reputations. What appears, on the surface, as commentary about temperament or mental balance operates as a structural denial of political standing itself.

What makes this strategy especially dangerous is its plausibility and its cultural reach. It draws on widely shared assumptions about rationality, emotional control, and credibility that preexist any particular regime or ideology. It exploits the fear of appearing unreasonable and the stigma historically attached to mental disorder, transforming those fears into instruments of discipline. In doing so, it recruits society itself as an enforcer. Critics withdraw preemptively. Institutions hesitate to associate. Observers learn to equate seriousness with acquiescence and moderation with silence. Power does not need to compel silence when it can teach people to doubt the sanity, motives, or stability of those who speak.

The Roman case demonstrates that this is not a pathology of modern media or contemporary polarization alone. It is a structural temptation wherever authority becomes insulated from accountability. When rulers or movements claim the ability to define what counts as rational, they claim dominion over the boundaries of political reality. Disagreement ceases to be a shared civic act and becomes a risk marker. The cost is not only the silencing of individual voices but the erosion of a culture capable of sustaining principled conflict.

Sanity, in political life, cannot be allowed to become a loyalty test. Democratic disagreement depends on the presumption that opponents are rational agents acting in good faith, even when profoundly wrong. When that presumption collapses, so does the possibility of persuasion, compromise, and learning. The lesson that emerges across centuries is stark but necessary: the health of a political system is measured not by how it treats agreement, but by how it permits disagreement to remain intelligible, answerable, and fully human.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1951.

- —-. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970.

- Beard, Mary. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- Bhatt, Shreyaa. “The Augustan Principate and the Emergence of Biopolitics: A Comparative Historical Perspective.” Foucault Studies 22 (2017), 72-93.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited and translated by John B. Thompson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Drews, Robert. “The Christos and Caligula’s Statue.” Journal of Early Christian History 14:3 (2024), 95-99.

- Foucault, Michel. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Vintage Books, 1961.

- —-. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

- —-. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976. New York: Picador, 1976.

- Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Lakoff, George. Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966.

- Rosenberg, Shawn W. The Not So Common Sense: Differences in How People Judge Social and Political Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Seneca. De Clementia. Translated by Susanna Braund. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2018.

- Suetonius. Caligula. In The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. London: Penguin Classics.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. London: Penguin Classics.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by Michael Grant. London: Penguin Classics.

- Taylor, N.H. “Popular Opposition to Caligula in Jewish Palestine.” Journal for the Study of Judaism 32:1 (2001), 54-70.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Winterling, Aloys. Caligula: A Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Wolin, Sheldon S. Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960.

- Yntema, Hessel E. “Roman Law and Its Influence on Western Civilization.” Cornell Law Review 35:1-4 (1949), 77-88.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.