The treatment of defeated claimants and rebel nobles after Bosworth reveals a disciplined and sustained distinction between acknowledgment and honor.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Victory, Legitimacy, and the Problem of Memory

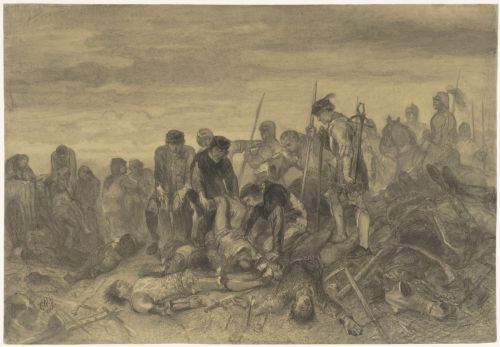

The conclusion of the Wars of the Roses in 1485 marked not merely the end of a dynastic conflict but the resolution of a prolonged crisis of political legitimacy in England. For more than three decades, royal authority had been contested through shifting alliances, intermittent warfare, and rival claims that blurred the boundaries between lawful succession and armed challenge. The Battle of Bosworth Field brought this instability to a decisive close by eliminating the last effective Yorkist king and enabling the accession of Henry Tudor. Yet the significance of Bosworth extended beyond the battlefield. Military victory resolved the immediate question of rule, but it did not automatically settle the deeper problem of how a fractured political past would be integrated into a stable present. The new regime faced not only the task of governing but also the burden of narrating how the realm had arrived at its restored order.

Late medieval political culture did not treat memory as neutral or automatic. Chronicles, genealogies, sermons, and public ritual served as instruments through which authority was explained, justified, and normalized. Defeat carried consequences that extended beyond the battlefield, shaping reputations, legal standing, and historical interpretation for generations. The question confronting the early Tudor state was not whether the defeated would be remembered, since erasure was neither possible nor desirable, but how that remembrance would be framed. The distinction between recording events and honoring actors lay at the center of postwar settlement.

In the aftermath of Bosworth, the Tudor monarchy permitted the defeated to remain present in historical narrative while carefully withholding the symbols of public honor that might have transformed them into tragic exemplars or moral counterweights to the new dynasty. Fallen claimants and rebel nobles appeared in chronicles, genealogies, and later historical accounts, where their actions could be examined, criticized, or contextualized. What they did not receive was the language of civic praise or the forms of commemoration that conferred legitimacy through sympathy. There were no sanctioned monuments mourning their cause, no ritualized remembrance that invited identification with their loss, and no official gestures that blurred the moral asymmetry between victor and vanquished. This approach reflected a deliberate refusal to convert defeat into dignity. Loss did not become virtue simply because it could be narrated, nor did political failure acquire legitimacy through retrospective pathos.

Tudor handling of memory after Bosworth was neither accidental nor unusually harsh, but a calculated exercise in narrative control aimed at securing long-term stability. By distinguishing between historical acknowledgment and public veneration, the regime closed the dynastic struggle without inviting its revival through sympathetic remembrance. The treatment of the defeated after the Wars of the Roses demonstrates how states that endure preserve memory while disciplining honor, ensuring that the record of conflict does not undermine the legitimacy established by victory.

The Wars of the Roses and the Meaning of Defeat

The Wars of the Roses unfolded within a political culture that did not romanticize failure or detach moral judgment from outcome. Dynastic conflict in fifteenth-century England was understood as a contest over lawful authority rooted in lineage, recognition, and the capacity to rule, not merely as a sequence of personal rivalries or heroic struggles. Claimants advanced their causes through force precisely because legitimacy was uncertain, but that uncertainty was resolved decisively by victory or defeat. Those who failed to secure the throne were not treated as tragic figures undone by misfortune or circumstance, but as actors whose inability to prevail exposed the insufficiency of their claims. Defeat settled legitimacy as decisively as victory affirmed it, and political meaning flowed from results rather than intentions, rhetoric, or perceived injustice.

Noble participation in rebellion carried consequences that were structural rather than symbolic. Allegiance to a losing claimant exposed families to attainder, confiscation of lands, and long-term exclusion from political influence, often extending across generations. These penalties were not understood as moral commentary on personal character but as instruments of settlement designed to prevent renewed conflict. In a realm repeatedly destabilized by private armies, shifting loyalties, and opportunistic alliances, ambiguity was dangerous. Clear and durable consequences signaled that unsuccessful challenges to royal authority would not be softened by retrospective sympathy. Loss fixed reputations as firmly as it altered fortunes, reinforcing the principle that political action carried irreversible risk.

The language used to describe the conflict in contemporary and near-contemporary sources reinforces this understanding. Chronicles portrayed battles, betrayals, and executions in pragmatic terms, emphasizing the restoration or disruption of order rather than the nobility of resistance. Even when individual courage was acknowledged, it did not translate into approval of the cause itself. Martial valor did not outweigh the failure to secure lawful rule. The distinction between bravery and legitimacy remained intact.

Defeat in the Wars of the Roses did not invite a counter-narrative of righteous opposition. Unlike later romantic traditions that elevate the defeated as moral witnesses or victims of historical injustice, fifteenth-century England offered no cultural script in which loss conferred ethical distinction. The political community did not seek consolation through heroic failure or redemptive memory. Instead, stability depended on reinforcing the finality of outcomes and discouraging the belief that unsuccessful claimants might yet command sympathy powerful enough to revive their cause. To reframe defeat as virtue would have undermined the very closure the realm required after decades of instability.

This understanding shaped how memory functioned during and after the conflict. The defeated were remembered as part of a sequence of disorder that culminated in resolution, not as exemplars standing outside or above the political process. Their presence in historical accounts served explanatory rather than commemorative purposes. Recording defeat clarified how instability arose and why it ended; it did not invite moral identification with those who lost.

By the time Bosworth Field was fought, this logic was well established. The war’s long duration had exhausted tolerance for ambiguity, and the political culture was primed for closure rather than reflection. The meaning of defeat was already fixed: loss marked the end of a claim, not the beginning of a legend. This context is essential for understanding why the Tudor regime could remember its defeated rivals without elevating them, and why doing so appeared neither novel nor controversial to contemporaries.

Bosworth Field as Political Closure

The Battle of Bosworth Field was not merely the final engagement of the Wars of the Roses but a decisive moment of political closure produced through unambiguous outcome rather than negotiation or compromise. The death of Richard III on the battlefield eliminated the last reigning Yorkist monarch and extinguished the most immediate dynastic alternative to Tudor rule. Unlike earlier confrontations in the conflict, Bosworth did not conclude with restoration followed by renewed contest or uneasy coexistence between rival houses. Its finality lay in the physical removal of a king whose claim, however disputed, had embodied the persistence of dynastic instability. The absence of survival, flight, or exile denied the defeated cause any living center around which memory or resistance might later coalesce.

Bosworth’s significance also derived from its timing and broader political context. By 1485, England had endured more than three decades of intermittent civil war marked by shifting allegiances, repeated depositions, and fragile settlements that repeatedly failed to endure. Political society had grown weary of provisional victories and unresolved claims that invited renewed conflict. The triumph of Henry Tudor was received not simply as the success of another faction but as an opportunity to impose finality on a struggle that had long resisted closure. The battlefield outcome allowed the new regime to present the war’s end as decisive rather than contingent, offering a narrative of resolution that earlier victories had been unable to sustain.

The manner in which Richard III died further reinforced this closure. Falling in combat rather than retreating or negotiating exile, Richard left no space for alternative futures or rehabilitative narratives. His death foreclosed the possibility of rival courts, lingering claimants with royal stature, or symbolic continuity for the defeated cause. This absence mattered. Political memory could acknowledge Richard’s reign and downfall without confronting an enduring Yorkist presence capable of demanding honor or recognition.

Bosworth also enabled the Tudors to redefine legitimacy retrospectively. Victory allowed Henry VII to frame his accession as the restoration of order rather than the triumph of a rebel claimant. By marrying Elizabeth of York and emphasizing dynastic union, the regime absorbed the Yorkist line into the Tudor settlement while simultaneously dissolving it as a competing authority. The war was narratively resolved not through reconciliation of equals but through the subsumption of defeat into a new and singular legitimacy.

Bosworth functioned as both an ending and a boundary, fixing not only the conclusion of the dynastic struggle but the terms under which it could be remembered. The battle marked the point at which contest gave way to authority and ambiguity yielded to settlement. Defeat at Bosworth did not generate a tradition of tragic loss or moral vindication for the fallen. Instead, it became the final chapter in a chronicle of disorder whose resolution justified the authority that followed. The political meaning of the battle lay not only in who prevailed, but in how decisively loss foreclosed the possibility that those who fell opposing the new regime might later be remembered as honorable alternatives rather than defeated challengers.

Tudor Control of Public Memory

The consolidation of Tudor power after Bosworth depended not only on military success and dynastic settlement but on the careful management of how the recent past was publicly remembered. Memory posed a distinct political risk. The Wars of the Roses had demonstrated how unresolved narratives, competing claims, and lingering loyalties could sustain instability long after battles were fought. The Tudor regime approached public memory as a matter of governance, shaping how defeat and victory would be recorded, discussed, and understood within the realm.

Central to this effort was a clear separation between historical record and public honor. The defeated were not erased from history, nor were they driven into silence. Chronicles continued to recount their actions, genealogies preserved their lineage, and scholars examined their decisions, alliances, and failures with considerable detail. What was withheld was the language and ritual of honor that might invite public sympathy or moral elevation. There were no state-sponsored monuments to fallen Yorkist leaders, no civic commemorations of their cause, and no sanctioned mourning that framed their defeat as tragic loss. Memory was permitted to exist as explanation and instruction, not as veneration. This distinction allowed the past to be known without allowing it to compete with the legitimacy of the present.

Royal patronage of historiography played a crucial role in sustaining this balance. Tudor-supported chroniclers framed the Wars of the Roses as a period of disorder whose very excess justified the necessity of firm and unified rule. Writers such as Polydore Vergil presented the conflict as a cautionary narrative, emphasizing the destructive consequences of divided sovereignty and rival dynastic ambition. Within this framework, defeated claimants appeared not as noble alternatives crushed by fate, but as contributors to prolonged instability whose failure clarified the moral and political necessity of the Tudor settlement. Their inclusion in historical writing was neither celebratory nor vindictive. It served to stabilize interpretation by locating defeat within a broader story of disorder resolved by legitimate authority.

Public ritual reinforced this narrative discipline. Coronations, progresses, and liturgical observances emphasized unity, continuity, and the end of division. The symbolic language of reconciliation was directed toward the realm as a whole, not toward honoring those who had opposed the crown. Even acts of clemency or pardon were carefully framed as demonstrations of royal mercy rather than acknowledgments of moral equivalence. The defeated were reintegrated as subjects, not elevated as figures deserving admiration.

The absence of heroic memorialization was itself a political signal. By denying defeated nobles the status of tragic exemplars, the Tudor state foreclosed the possibility that loss could be reinterpreted as virtue. This restraint discouraged future challengers from imagining that failure might still yield moral prestige. The message was implicit but unmistakable: rebellion might be recorded, but it would not be rewarded with honor simply because it had occurred.

Through these combined practices, the Tudors established a durable framework for remembering civil war without perpetuating it. Public memory acknowledged the reality of conflict while carefully disciplining its moral implications and symbolic reach. The defeated remained visible in historical narrative, but they were fixed in place as defeated, not transformed into figures of admiration or sympathy capable of unsettling the settlement that followed. In this way, control of memory functioned as an extension of political authority, ensuring that the narrative of Bosworth closed the Wars of the Roses rather than reopening them through retrospective identification with those who lost.

Why Defeat Was Not Recast as Virtue

The Tudor refusal to recast defeat as virtue was rooted in political necessity rather than moral severity. In the aftermath of prolonged civil war, the central task of the new regime was to stabilize authority and prevent the reemergence of dynastic contest. To elevate defeated claimants or rebel nobles as tragic heroes would have undermined that objective by preserving the emotional and symbolic resources of opposition. Sympathy could easily become a substitute for legitimacy, and remembrance framed as moral loss might invite renewed identification with causes the state had decisively rejected.

Late medieval English political culture also lacked the ideological frameworks that later generations would use to romanticize failure. Political judgment did not separate intention from outcome in the way modern moral narratives often do. Courage, sincerity, or personal sacrifice did not generate independent claims to legitimacy when detached from success. Authority was evaluated in terms of its capacity to govern and restore order, not the perceived righteousness of resistance. Defeat indicated not noble dissent but error, miscalculation, or insufficiency of claim. To reinterpret loss as virtue would have required a moral inversion foreign to the assumptions of fifteenth-century governance, one that risked weakening the clarity upon which political settlement depended.

The practical dangers of heroizing defeat were equally apparent. The Wars of the Roses had repeatedly demonstrated how memory could sustain instability long after armies dispersed. Fallen leaders, if granted moral prestige, might continue to command loyalty through symbolism even when stripped of power. The Tudor regime understood that rebellion did not end simply with the removal of a claimant; it ended when the claimant’s cause lost its capacity to inspire. By refusing to frame defeat as tragic or redemptive, the state denied future challengers the consolation that failure might still yield honor or historical vindication. Defeat was allowed to close a claim rather than preserve it in cultural memory as an unfinished moral struggle.

In refusing to sanctify loss, the Tudors reinforced a broader principle of governance grounded in narrative discipline. Authority depended not only on lineage or coercion but on the ability to impose moral finality. Memory of defeat was permitted, even encouraged, as historical explanation, but its ethical meaning was constrained. Loss did not confer dignity, and remembrance did not generate virtue. By maintaining this asymmetry, the Tudor settlement ensured that the past clarified the legitimacy of the present rather than challenging it through retrospective sympathy.

Remembered but Not Honored: Bosworth’s Historical Afterlife

In the decades following Bosworth Field, the battle remained firmly embedded in England’s historical consciousness without becoming a site of public mourning or heroic commemoration for the defeated. Chroniclers, scholars, and later historians continued to revisit the events of 1485, examining the collapse of Yorkist power and the political conditions that made Tudor accession possible. This sustained attention ensured that Bosworth was neither forgotten nor obscured, yet the manner of remembrance was carefully delimited. The battle was treated as a decisive terminus to civil war and as the precondition for restored order, not as a moral catastrophe demanding sympathy for those who lost. Memory functioned analytically rather than emotionally, reinforcing closure rather than inviting lament.

The figure of Richard III illustrates this distinction with particular clarity. His reign and death were extensively discussed, debated, and reinterpreted across generations, but these discussions unfolded within scholarly, literary, and historiographical contexts rather than through sanctioned public honor. Writers assessed his policies, character, and conduct in battle, sometimes acknowledging administrative competence or personal bravery. Such evaluations, however, remained detached from moral rehabilitation. Richard’s defeat was not framed as injustice, nor was his fall treated as a tragedy requiring redress. He remained an object of inquiry and controversy, not of veneration. The absence of official commemoration ensured that intellectual curiosity did not harden into civic admiration or symbolic loyalty.

This pattern extended beyond Richard himself to the broader Yorkist cause. Defeated nobles appeared in genealogies and historical accounts as part of the narrative of disorder that preceded Tudor consolidation. Their memory functioned as explanation rather than inspiration. The lack of monuments, anniversaries, or ritualized remembrance prevented the crystallization of a heroic tradition around their loss. Bosworth retained its meaning as closure rather than as a wound kept open by commemorative practice.

Bosworth’s historical afterlife reflects the success of Tudor narrative control. The battle could be studied, debated, and even reinterpreted without threatening the legitimacy it helped establish. Remembering the defeated did not require honoring them, and historical attention did not confer moral rehabilitation. By allowing memory to persist while disciplining its symbolic implications, the Tudor settlement ensured that Bosworth remained a lesson in finality rather than a foundation for counter-myth.

Conclusion: Losing the War Meant Losing the Narrative

The Battle of Bosworth Field closed the Wars of the Roses not only through military victory but through narrative resolution deliberately imposed and carefully maintained. The Tudor settlement demonstrates that political authority depends as much on controlling the meaning of the past as on securing power in the present. Bosworth did more than remove a rival king; it established the terms under which the conflict itself would be remembered. Defeat did not erase the defeated from history, nor did it require their demonization. Instead, it decisively stripped their cause of moral and symbolic authority. By allowing the record of loss to persist while denying it dignifying interpretation, the Tudor regime ensured that memory functioned as confirmation of settlement rather than as a reservoir of grievance.

The treatment of defeated claimants and rebel nobles after Bosworth reveals a disciplined and sustained distinction between acknowledgment and honor. Chronicles preserved their actions, historians debated their decisions, and genealogies recorded their lineage as part of the political past of the realm. What was consistently denied was the transformation of defeat into tragedy worthy of civic sympathy or public reverence. There were no official memorials to fallen Yorkist leaders, no ritualized anniversaries of loss, and no sanctioned language of mourning that elevated their cause. This absence was not accidental. It reflected a conscious refusal to allow failure to acquire retrospective dignity. Loss concluded claims instead of preserving them as moral alternatives, ensuring that defeat remained an endpoint rather than an invitation to reinterpretation.

This approach was neither vindictive nor uniquely Tudor. It reflected a broader understanding of how political memory functions in the aftermath of civil conflict. To sanctify defeat would have invited future challengers to imagine that failure might still yield legitimacy through posthumous admiration. The Tudor refusal to do so reinforced the finality of settlement and denied rebellion the consolation of honor. In this framework, legitimacy flowed from resolution rather than from empathy for those who had lost.

Bosworth’s enduring lesson lies in this clarity. States that endure remember rebellion without rewarding it, record defeat without ennobling it, and permit history without allowing it to undermine authority. Losing the war meant losing the narrative, not through enforced silence but through disciplined memory. The Wars of the Roses ended when defeat ceased to be redeemable, and Bosworth marked the point at which loss became final not only on the battlefield, but in the story the realm told about itself.

Bibliography

- Betteridge, Thomas. Tudor Histories of the English Past: Writing the Nation’s Past. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999.

- Carpenter, Christine. The Wars of the Roses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Drozdzewski, Danielle, Emma Waterton, and Shanti Sumartojo. “Cultural Memory and Identity in the Context of War: Experiential, Place-Based and Political Concerns.” International Review of the Red Cross 101:1 (2019), 251-272.

- Goodman, Anthony. The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–1497. London: Routledge, 1981.

- Gunn, Steven. Henry VII’s New Men and the Making of Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Hicks, Michael. Richard III. Stroud: Tempus, 1991.

- Ingram, Mike. “Interpreting the Battle of Bosworth Field.” The History Press (08.22.2016).

- Larson, Kajsa. “Remembering the Thirteen Roses: Blurring Fact and Fiction.” Nomenclatura: aproximaciones a los estudios hispánicos 2:8 (2012).

- Marshall, Peter. Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- McKelvie, Gordon. “Fear, Hatred and Strategy during the Wars of the Roses.” History (HIS) 107:374 (2012), 3-24.

- Pollard, A. J. The Wars of the Roses. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1988.

- Thornton, Tim. “The Battle of Sandeford: Henry Tudor’s Understanding of the Meaning of Bosworth Field.” Historical Research 78:201 (2005), 436-442.

- Vergil, Polydore. Anglica Historia. Edited and translated by Dana F. Sutton. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Watts, John. The Making of Polities: Europe, 1300–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.