The decision to curtail maritime engagement followed from domestic political recalibration, fiscal prioritization, and ideological conviction rather than incapacity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Zheng He and the Apex of Ming Maritime Power (1405–1433)

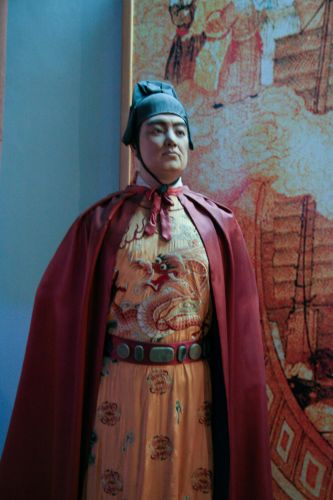

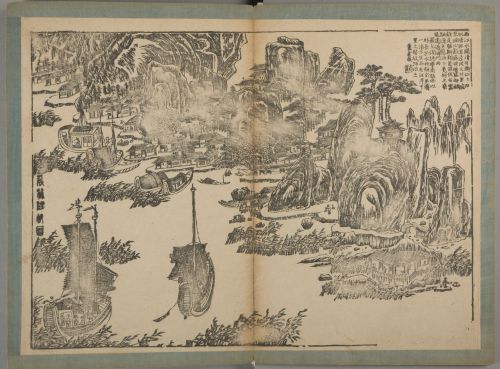

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming Dynasty sponsored a series of maritime expeditions under the command of the eunuch admiral Zheng He that represented the most ambitious naval undertaking of the premodern world. Dispatched during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, these voyages projected Chinese power across Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and as far as the eastern coast of Africa. The scale of the fleets astonished contemporary observers. Contemporary records describe hundreds of vessels, including massive “treasure ships,” accompanied by thousands of sailors, soldiers, interpreters, and officials. Whatever debates persist about the precise dimensions of these ships, there is little dispute that Ming naval capacity at this moment surpassed that of any European power of the era. The voyages signaled technological sophistication, logistical coordination, and state-sponsored ambition on an extraordinary scale.

The purpose of these expeditions was not colonization in the European sense but the consolidation of a tributary and diplomatic network. Zheng He’s fleets carried silks, porcelains, and imperial proclamations, establishing or reaffirming ties with polities across the maritime world. In return, foreign rulers presented tribute and acknowledged the symbolic supremacy of the Ming court. The voyages reinforced a Sino-centric vision of international order in which China functioned as the gravitational center of exchange and legitimacy. Participation in this order was mutually advantageous. Local rulers gained prestige and access to Chinese goods, while the Ming court demonstrated its capacity to command respect across vast distances.

The geographic reach of the expeditions underscores the structural centrality China achieved during this period. Ports in present-day Vietnam, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Arabia received the fleets, and the final voyages reached the Swahili Coast of East Africa. The Indian Ocean, long a vibrant commercial zone, became integrated more visibly into Ming diplomatic circuits. While private trade had flourished for centuries, Zheng He’s missions layered formal imperial recognition atop existing commercial networks. The Ming state did not invent maritime trade in the region, but it elevated its role from participant to orchestrator, embedding Chinese authority within the connective tissue of Afro-Eurasian exchange.

The material foundations of this maritime apex were formidable and deeply institutional. Ming shipyards, particularly those along the Yangtze, constructed large oceangoing vessels using advanced techniques in hull design, watertight bulkheads, sternpost rudders, and compartmentalized storage that enhanced both durability and range. Navigational knowledge, including systematic use of the magnetic compass, star charts, and detailed route records, enabled sustained long-distance travel across monsoon-driven sea lanes. The state mobilized immense resources to provision and coordinate these fleets, drawing upon tax revenues, corvée labor systems, and a sophisticated bureaucratic apparatus capable of organizing thousands of personnel across multiple voyages. Timber acquisition, dockyard management, food storage, armament preparation, and diplomatic protocol all required coordinated administrative oversight. The voyages demonstrated not only naval prowess but administrative depth. Maritime engagement was an expression of centralized state power, revealing the Ming court’s capacity to marshal material, technical, and human resources on a continental scale.

Equally significant was the political symbolism embedded in the voyages. The Yongle Emperor had seized the throne through civil war and sought to legitimize his rule through visible demonstrations of grandeur and universal authority. Maritime expansion served this purpose effectively. Each foreign embassy returning to Nanjing reinforced the narrative of a world orbiting the Ming court. The fleets became floating manifestations of imperial confidence. Centrality was enacted, not merely assumed. Through ritual exchanges and diplomatic choreography, China presented itself as indispensable to the regional order.

By the early 1430s, Ming China stood at the apex of maritime engagement, not simply in terms of fleet size but in terms of systemic influence. Its ships traversed vast distances, its goods circulated widely, and its court commanded deference across the Indian Ocean basin. The tributary framework provided ideological structure, while naval presence supplied practical enforcement and reassurance. In structural terms, China occupied a nodal position in the early fifteenth-century maritime system, linking disparate commercial zones into a recognizable diplomatic sphere. This centrality rested upon active participation, state sponsorship, and credible projection of authority. The subsequent decision to curtail these voyages would not represent technological incapacity or sudden decline. It would represent deliberate retrenchment from a position of extraordinary outward strength. To understand the implications of that withdrawal, one must first appreciate the scale and sophistication of the engagement that preceded it.

Internal Political Shifts and the Turn Inward

The cessation of Zheng He’s voyages was not the product of maritime failure but of domestic political recalibration. After the death of the Yongle Emperor in 1424, court priorities shifted. The Ming state faced mounting fiscal pressures, frontier security concerns along the northern borders, and ongoing administrative strain from large-scale imperial projects. Successor emperors proved less committed to maritime expansion, and the political coalition that had supported the voyages began to lose influence. The transition marked a reorientation of strategic emphasis from outward projection to internal consolidation.

Central to this shift was the rivalry between eunuch officials, who had often championed maritime initiatives, and Confucian scholar-officials, who tended to view such ventures with skepticism or outright opposition. The treasure fleets had been closely associated with eunuch leadership, particularly Zheng He himself, whose authority derived from imperial favor rather than examination-based bureaucratic advancement. Scholar-officials frequently criticized eunuch power as destabilizing and morally corrosive, and the voyages became entangled in broader institutional struggles over influence within the court. Maritime expeditions were portrayed as extravagant displays that drained resources and enhanced eunuch prestige rather than strengthening the moral fabric of the state. In contrast, Confucian administrators emphasized agrarian productivity, population stability, and bureaucratic discipline as the legitimate pillars of imperial endurance. As their influence reasserted itself, policies favoring restrained expenditure and inward focus gained ascendancy.

Fiscal considerations further reinforced this inward turn. The construction and provisioning of massive fleets demanded significant allocation of timber, labor, and financial resources drawn from provincial revenues and state granaries. These expenditures occurred alongside other costly initiatives, including palace construction and military campaigns. At the same time, the Ming court confronted renewed concerns about frontier defense, particularly along the northern steppe regions where Mongol forces remained a persistent threat. Maintaining garrisons, fortifying defensive lines, and supplying frontier troops required sustained financial commitment. Redirecting resources from maritime display to terrestrial security reflected a rational reprioritization within the court’s evolving strategic framework. In this calculus, naval expeditions across distant seas offered symbolic prestige, but frontier vulnerability posed tangible risk. Maritime engagement was not abandoned because it was impossible, but because it was deemed less urgent than protecting the empire’s immediate territorial boundaries.

Ideological factors also shaped the retrenchment. The Confucian bureaucratic ethos privileged stability, hierarchy, and agrarian self-sufficiency. While overseas trade had long been a feature of Chinese coastal life, state-sponsored naval projection was more difficult to reconcile with traditional moral and administrative principles. The tributary system could function symbolically without continual naval reinforcement, and many officials believed that China’s cultural prestige required no active maritime assertion. The empire’s centrality was assumed to be inherent rather than contingent upon sustained outward engagement.

By the mid-fifteenth century, the combined effect of political rivalry, fiscal constraint, and ideological realignment produced a decisive contraction of state-sponsored maritime activity. Shipbuilding regulations tightened, and official support for long-distance expeditions faded. The turn inward did not signal economic collapse or technological regression. It represented a strategic choice rooted in domestic governance priorities. Yet this recalibration would have consequences beyond the court’s immediate calculations, altering China’s role within the broader maritime ecosystem of the Indian Ocean world.

Maritime Bans and Structural Contraction

The inward turn of the Ming court did not remain rhetorical. It translated into policy through the enforcement of maritime prohibitions known collectively as the haijin. These measures, implemented intermittently across the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, restricted private overseas trade and limited ship construction along the southeastern coast. While coastal commerce had long been embedded in regional life and had flourished through both official and unofficial channels, the new restrictions aimed to curtail unsanctioned maritime activity and reassert central authority over cross-border exchange. The state sought to confine foreign trade to officially regulated tributary missions, narrowing the channels through which goods, people, and information circulated. By doing so, Ming policymakers attempted to preserve social order and fiscal oversight, even at the cost of reducing the empire’s outward commercial engagement. Maritime control became synonymous with domestic stability rather than international expansion.

The bans did not eliminate maritime commerce entirely, but they altered its structure in significant and often unintended ways. Restrictions on vessel size and shipyard production constrained the development of large oceangoing fleets outside direct state supervision. Merchants faced legal penalties for unauthorized voyages, pushing a portion of trade into gray and black markets along the coast. Smuggling networks expanded, particularly in Fujian and Guangdong, where commercial traditions and diaspora connections were deeply rooted. In practice, these coastal communities maintained ties with Southeast Asian ports and overseas Chinese networks, often operating beyond formal state sanction. Rather than integrating private maritime initiative into a state-sponsored framework, the Ming government treated it as a problem of order and discipline. This approach reshaped incentives, encouraging clandestine exchange while diminishing official oversight. The effect was not economic isolation in absolute terms, but the contraction of formal, state-backed maritime centrality.

This contraction reshaped the relationship between coastal economies and imperial authority. Local communities continued to participate in regional exchange, yet the absence of consistent official support limited China’s role as an organizer of long-distance maritime systems. Where Zheng He’s fleets had once embodied imperial presence across the Indian Ocean, the haijin signaled withdrawal from active network management. The Ming court retained immense domestic productive capacity, but it ceded initiative in shaping the rules and routes of overseas commerce. Centrality shifted from active coordination to reactive regulation.

Structural contraction does not require total disengagement to alter systemic position. By restricting outward maritime expansion and constraining private enterprise, the Ming state reduced its visibility and influence within evolving global trade circuits. The Indian Ocean world continued to function as a vibrant commercial zone, but China’s role within it became more limited and mediated. Trade networks are adaptive. When one participant narrows engagement, others fill connective space. The maritime bans marked not an immediate collapse, but a gradual repositioning within a dynamic and increasingly competitive economic environment.

The Vacuum and European Expansion

The contraction of Ming maritime engagement did not create an empty ocean, but it did create opportunity space within an already dynamic commercial system. The Indian Ocean had long supported robust exchange among Arab, Indian, Southeast Asian, and East African merchants. What shifted in the late fifteenth century was not the existence of trade, but the scale of European intervention into its connective routes. When Vasco da Gama reached the Indian Ocean in 1498, the Portuguese entered an established network rather than discovering an untouched frontier. Yet the absence of sustained Ming naval presence meant that no dominant East Asian power stood ready to contest their incremental expansion.

Portuguese strategy differed markedly from the earlier Ming approach. Rather than operating within a tribute framework centered on symbolic hierarchy, Portuguese authorities sought fortified nodes of control. Through the seizure of key ports such as Goa and Malacca, and the establishment of a string of fortified trading posts, they inserted themselves as armed intermediaries within regional commerce. The Estado da Índia leveraged naval artillery and convoy systems to impose licensing regimes and extract customs revenues. Control over chokepoints allowed a relatively small European power to exert disproportionate influence over maritime circulation. Expansion did not require territorial conquest on a continental scale. It required control of strategic connectors.

The Spanish followed a complementary trajectory in the Pacific, establishing Manila in 1571 as a hub linking American silver to Asian markets. The Manila galleon system connected New World bullion to Chinese demand for silver, integrating the Americas, Europe, and East Asia into a single commercial circuit. While China remained a major producer and consumer within this emerging global economy, it did not structure the shipping routes that enabled transoceanic exchange. Silver flowed into the Ming economy in vast quantities, but the maritime infrastructure facilitating that flow increasingly rested in European hands.

By the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company introduced a further stage of commercial militarization. Combining corporate structure with naval force, the Dutch established trading monopolies and contested Iberian dominance across the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. Their methods blended financial innovation with coercive capacity, reinforcing a model in which maritime trade was inseparable from organized violence. European expansion was not uniform or uncontested, yet it steadily increased European participation in shaping long-distance trade networks. The connective architecture of the global economy became increasingly influenced by Atlantic-based powers.

Important to note is not that Ming withdrawal directly caused European dominance, but that disengagement reduced Chinese capacity to shape the terms of expanding global exchange. The vacuum was relative, not absolute. China remained economically powerful and demographically vast. Yet as European actors inserted themselves into maritime chokepoints and trade circuits, they accumulated structural leverage. Control over routes, licensing, and shipping infrastructure translated into influence over flows of goods and silver. In adaptive trade ecosystems, the actors who maintain active maritime presence and institutional innovation tend to define the network’s architecture. Withdrawal does not erase economic strength, but it alters who sets the rules of connection.

Trade Networks as Adaptive Ecosystems

The Ming case illustrates a broader structural principle: trade networks function less like fixed hierarchies and more like adaptive ecosystems. They respond to shifts in participation, security, capital flows, and institutional innovation. No single actor remains central by default. Centrality is maintained through sustained engagement, logistical investment, and credible commitment to protecting circulation. When one major participant reduces its outward maritime presence, the network does not collapse. It recalibrates around those who remain active.

China in the sixteenth century remained an economic giant. Its population, agricultural productivity, and artisanal output made it one of the largest markets in the world. Demand for silver, especially after fiscal reforms such as the Single Whip reforms consolidated tax payments into silver obligations, drew immense quantities of American bullion into East Asia. This silver flowed through Manila and other nodes before entering Chinese markets, integrating China into an increasingly global monetary system. In this sense, China functioned as a gravitational core of demand, pulling precious metals across oceans and shaping price structures far beyond its borders. Yet gravitational pull differs from architectural control. While silver flowed toward Ming markets, the shipping routes, convoy systems, and fortified nodes that managed intercontinental movement were increasingly organized and secured by European maritime powers.

This distinction between scale and structure is crucial. A large economy can exert enormous influence through consumption and production yet still lack control over connective infrastructure. During the height of Zheng He’s voyages, the Ming state had directly sponsored and shaped maritime pathways. After withdrawal, Chinese merchants continued to trade, often through private and diaspora networks, but the state no longer coordinated long-distance maritime architecture. As European actors secured chokepoints and institutionalized maritime corporations, they accumulated structural advantages in regulating global exchange.

Adaptive ecosystems reward sustained participation and innovation. The Portuguese cartaz system, the Spanish Manila galleon link, and the Dutch joint-stock corporate model each represented institutional experiments in organizing maritime commerce. These mechanisms combined naval force, financial structuring, and legal frameworks to create durable patterns of exchange. Licensing systems, convoy protections, and fortified ports did more than facilitate trade; they structured it. Merchants seeking predictable security gravitated toward routes under consistent protection, even if that protection carried costs. These institutional innovations reinforced European leverage over maritime flows. Trade networks, responding to security, credit availability, and enforceable contracts, adjusted accordingly.

China’s continued prosperity did not prevent this structural shift. The Ming economy absorbed silver, maintained vibrant domestic markets, and supported large urban populations. Commercialization intensified within China even as official maritime sponsorship receded. Yet the center of coordination for transoceanic exchange migrated outward. Atlantic and Indian Ocean powers increasingly shaped shipping norms, commercial law practices, and naval balances. Centrality became associated with those who controlled routes, issued licenses, and enforced maritime claims rather than those who anchored demand alone. The ecosystem reorganized around connective management and institutional innovation, gradually redefining where global economic authority appeared to reside.

The lesson is neither triumphalist nor deterministic. Trade systems do not reward isolation or punish it automatically. Rather, they respond to engagement patterns. A power that withdraws from active network management may retain internal strength while ceding external coordination. China did not collapse after maritime retrenchment. It remained large, wealthy, and culturally influential. Yet its position within the evolving global trade ecosystem shifted from architect to participant. In adaptive systems, centrality is sustained by presence. When presence narrows, others expand into the connective space.

Centrality versus Magnitude: The Strategic Cost of Withdrawal

The Ming experience clarifies an essential distinction between magnitude and centrality, two concepts often conflated in discussions of power. Magnitude refers to demographic weight, territorial scale, productive capacity, and internal economic vitality. It is measured in population size, agricultural output, fiscal revenue, and artisanal production. Centrality, by contrast, refers to positional influence within networks of exchange, finance, diplomacy, and security. It concerns who coordinates flows, who sets terms of interaction, and who manages connective infrastructure. A state may possess immense scale while gradually relinquishing its role as coordinator of wider systems. After the cessation of the treasure voyages and the enforcement of maritime restrictions, China remained one of the largest economies in the world, with thriving internal markets and significant technological sophistication. Its markets continued to attract foreign goods and silver, and its domestic commercial life intensified in many regions. Yet the architecture of long-distance maritime trade increasingly developed beyond direct Ming orchestration. Withdrawal did not reduce China’s size. It reduced its structural leverage within the broader Afro-Eurasian and emerging global system.

Strategic retrenchment can preserve domestic order while narrowing external influence, and in the Ming case it reflected coherent internal priorities. Policymakers sought to conserve resources, reinforce frontier defense against steppe incursions, and stabilize bureaucratic governance after periods of political contention. From the perspective of court administrators, these objectives addressed tangible and immediate threats. However, the cumulative effect of sustained maritime contraction was to shift initiative outward in ways that were not immediately apparent. Control over shipping routes, licensing regimes, convoy systems, and naval protection migrated to European powers that remained actively engaged in maritime expansion. Over successive decades, these actors accumulated navigational expertise, institutional frameworks, financial mechanisms, and military capacities that reinforced their systemic position. Experience in long-distance navigation and armed commercial organization became self-reinforcing advantages. Withdrawal carries opportunity costs that may not register in short-term stability metrics but compound gradually across generations, altering the balance of connective authority in subtle yet durable ways.

The distinction between active engagement and passive participation also matters. China continued to participate in global exchange through demand for silver and goods, but participation without coordination differs from leadership. States that shape shipping standards, commercial law, and maritime enforcement exercise disproportionate influence over the evolution of trade networks. By ceding that coordinating role, the Ming court limited its ability to define the rules of interaction. Centrality shifted toward those who managed routes and institutions rather than those who simply anchored consumption. The strategic cost of withdrawal lies not in immediate decline but in long-term repositioning within an evolving system.

The broader implication is structural rather than moral. Powers that reduce outward engagement may retain internal strength yet discover that network centrality migrates elsewhere. Engagement, innovation, and credible commitment sustain connective authority. Contraction, even when prudent domestically, can recalibrate systemic influence. The Ming case illustrates that magnitude alone does not guarantee enduring centrality. In adaptive global systems, the actors who remain visibly engaged in shaping routes and institutions tend to define the architecture of exchange. Withdrawal narrows that capacity, even if it preserves internal stability.

Contemporary Reversal: China’s Outward Turn in an Era of American Retrenchment

In the early twenty-first century, the strategic pattern appears reversed. Where the Ming court once withdrew from maritime coordination, contemporary China has pursued expanded engagement through infrastructure investment, trade agreements, and financial integration. Initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative seek to connect Asia, Africa, Europe, and Latin America through transportation corridors, ports, and energy networks. Participation in multilateral trade frameworks, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, positions China within large regional blocs even as the United States has signaled greater skepticism toward certain trade arrangements under President Donald Trump. The contrast is structural rather than rhetorical: one major power is investing in connective infrastructure while another debates the costs and terms of global economic leadership.

American economic nationalism during the Trump era has emphasized tariff leverage, domestic manufacturing revival, and reassessment of multilateral commitments. These policies are framed as corrective measures addressing trade imbalances and strategic dependency. Yet trade ecosystems respond not to rhetoric alone but to predictability and access. When tariffs rise or agreements are renegotiated under uncertain conditions, partner states seek diversification. Supply chains adjust incrementally, often shifting portions of production or sourcing to alternative markets. Retrenchment does not imply immediate collapse of American centrality, but it can stimulate hedging behaviors among allies and competitors alike.

China’s outward posture reflects an awareness of how network centrality is constructed. Investment in ports, rail corridors, and digital infrastructure enhances not only economic return but structural influence. Connectivity projects bind participating states into webs of financing, logistics, and regulatory coordination. While debates persist regarding debt sustainability and geopolitical implications, the broader pattern is one of active engagement. Centrality emerges from visible participation in shaping trade routes, standards, and institutional frameworks. In this sense, contemporary China appears to be applying lessons opposite to those of the fifteenth-century withdrawal.

The comparison does not predict a simple inversion of global hierarchy, nor does it assume inevitable American decline. The United States retains unmatched military capabilities, deep capital markets, and enduring institutional networks. The structural question, however, concerns engagement patterns. Trade ecosystems reward sustained connective investment and penalize unpredictability. If one major power signals contraction while another expands infrastructural and diplomatic reach, network centrality may gradually migrate. The lesson drawn from the Ming case remains applicable: magnitude endures, but centrality depends on participation.

Conclusion: Still Great, No Longer Central

The Ming maritime experience demonstrates that decline need not begin with weakness. At the moment of withdrawal, China was neither impoverished nor technologically backward. It remained demographically vast, economically productive, and administratively sophisticated. The decision to curtail maritime engagement followed from domestic political recalibration, fiscal prioritization, and ideological conviction rather than incapacity. Yet structural systems do not pause while one participant turns inward. Trade networks, financial flows, and maritime routes reorganize around those who remain actively engaged. The Ming state preserved magnitude but relinquished coordination. In doing so, it accepted a gradual shift from architect of regional connectivity to participant within networks increasingly shaped by others.

The long arc of early modern globalization underscores the cumulative nature of such repositioning. European powers did not eclipse China through immediate conquest of scale. They accumulated leverage incrementally by controlling chokepoints, formalizing shipping regimes, and institutionalizing maritime corporations. Experience compounded over generations. Naval logistics, financial instruments, and commercial law practices matured within frameworks of outward engagement. Meanwhile, China’s economy thrived internally, absorbing silver and sustaining commercial vitality, yet without directing the evolving connective architecture. The distinction between internal strength and systemic centrality became progressively visible.

This distinction remains analytically powerful in evaluating contemporary global dynamics. A state may retain immense productive capacity and domestic stability while its influence over the connective tissue of the global economy narrows. Centrality depends not solely on output but on participation in shaping routes, standards, and institutions. Engagement projects power beyond borders. Retrenchment, even when prudent, alters perception and influence across networks that reward consistency and infrastructural investment. The Ming case illustrates that strategic contraction carries opportunity costs that unfold gradually rather than immediately. It is the compounding of missed connective influence, not sudden collapse, that reshapes global position.

To be “still great” yet “no longer central” is not a verdict of failure but a structural diagnosis. Greatness measured by size, wealth, or cultural achievement can coexist with diminished capacity to define the rules of exchange. Centrality requires sustained outward commitment, credible presence, and institutional innovation. When these recede, adaptive systems recalibrate around those who remain active. The Ming experience offers neither triumphalism nor fatalism. It offers a reminder that power in interconnected systems is positional as much as material. Magnitude endures within borders. Centrality is negotiated across them.

Bibliography

- Atwell, William S. “International Bullion Flows and the Chinese Economy circa 1530–1650.” Past & Present 95 (1982): 68–90.

- Boxer, C. R. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415–1825. New York: Knopf, 1969.

- Brook, Timothy. The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- —-. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Dreyer, Edward L. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

- Fairbank, John King, and Merle Goldman. China: A New History. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Finlay, Robert. “The Voyages of Zheng He: Ideology, State Power, and Maritime Trade in Ming China.” Journal of The Historical Society 8:3 (2008), 327-347.

- Flynn, Dennis O., and Arturo Giráldez. “Born with a ‘Silver Spoon’: The Origin of World Trade in 1571.” Journal of World History 6:2 (1995): 201–221.

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook (various years).

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House, 1987.

- Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Naughton, Barry. The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy, 1978 to 2020. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2021.

- Office of the United States Trade Representative. Annual Reports (2017–2025).

- Perdue, Peter C. “China in the Early Modern World: Short Cuts, Myths and Realities.” Education about Asia 4:1 (1999), 21-26.

- Rolland, Nadège. China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2017.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500–1700: A Political and Economic History. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Wade, Geoff. “Ming China and Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century.” Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series 28 (2004).

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.16.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.