The agrarian history of ancient Mesopotamia offers one of the earliest and clearest demonstrations that economic collapse among small producers is rarely accidental.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Agriculture, Vulnerability, and the Architecture of Power

The earliest agrarian societies did not emerge on a foundation of abundance but on a precarious balance between labor and land. Agriculture promised stability only insofar as ecological conditions held and political systems restrained themselves. Where cultivation depended on irrigation and seasonal predictability as well as coordinated labor, even minor disruptions could ripple outward with disproportionate force. In these environments, the survival of small farming households was never guaranteed by effort alone. It was mediated by institutions that claimed authority over grain, land, and obligation.

This vulnerability was structural rather than episodic in ancient Mesopotamia. Family-scale farmers operated within systems that extracted surplus through taxation and commercial debt while offering limited protection when harvests failed. The state did not merely oversee agriculture but embedded itself within the grain economy through temples and palaces that stored surplus and issued rations in addition to extending credit. These institutions functioned as stabilizers in good years and as accelerants of dispossession in bad ones. The margin between subsistence and loss was thin enough that a single failed season could determine a household’s fate.

Power in these early states was architectural rather than purely coercive. Control over irrigation networks and storage facilities shaped outcomes long before force was applied. Grain was both sustenance and leverage. Debt was not an outlying circumstance but a predictable consequence of operating within a system where risk was privatized and security was centralized. As smallholders lost land to creditors, temples, or royal estates, consolidation followed patterns that were neither accidental nor temporary. The economic logic of the system favored scale, accumulation, and institutional endurance over household resilience.

The collapse of smallholders in ancient Mesopotamia represents one of the earliest documented cases of agrarian consolidation driven by macroeconomic pressure. Far from being a distant or alien phenomenon, this pattern reveals a recurring dynamic in which policy shocks and market disruptions strike small producers first, while large institutions absorb or exploit the fallout. By examining debt, grain systems, and state intervention in the Sumerian and Babylonian worlds, we can establish an historical framework that illuminates why similar pressures continue to reshape agrarian life whenever vulnerability is treated as a private failure rather than a public responsibility.

The Mesopotamian Agrarian World: Smallholders on Narrow Margins (c. 3000–1600 BCE)

Agriculture in ancient Mesopotamia rested on an environmental knife edge. The alluvial plains of Sumer and later Babylonia were fertile but unforgiving, dependent on carefully managed irrigation systems that required constant labor and coordination. Flooding could destroy fields just as easily as drought could desiccate them. Unlike rain-fed farming regions, Mesopotamian agriculture offered little ecological slack. Success depended on timing, maintenance, and collective infrastructure, all of which lay partly outside the control of individual households.

Most agricultural producers were smallholders cultivating modest plots worked primarily by family labor. These farms were not oriented toward accumulating surplus but toward survival. Seed grain had to be set aside and tools maintained. Labor was distributed across planting, irrigation upkeep, and harvest. Little remained after meeting subsistence needs. Any surplus was quickly absorbed by costs or obligatory deliveries owed to temples and palaces. The result was an agrarian population living close to the threshold of loss even in stable years.

Land tenure further constrained resilience. While many households held customary or legally recognized rights to their fields, ownership was rarely absolute in the modern sense. Fields were embedded within broader systems of obligation, whether tied to government lands and grants or service requirements. Failure to meet these obligations could result in forfeiture, not as punishment but as a routine legal outcome. Smallholders operated in a world where land was both livelihood and collateral and always vulnerable to external claims.

Credit intensified this exposure. Grain loans were common and often essential, particularly in years of poor harvest or delayed flooding. These loans, frequently in silver or equivalent denominations, carried repayment expectations that did not adjust to ecological reality. A failed crop did not suspend obligation. Instead, it transformed subsistence shortfall into legal debt. Repeated borrowing locked households into cycles that steadily eroded their autonomy and landholdings.

What emerges from the documentary and archaeological record is not a picture of reckless farming or moral failure but of structural fragility. Smallholders were rational actors within a system that offered them no meaningful buffer against disruption. Their narrow margins were not accidental but intrinsic to an agrarian order that prioritized institutional stability over household security. This imbalance set the stage for the recurring waves of dispossession and consolidation that would define Mesopotamian political economy for centuries.

Grain as Power: Temples, Palaces, and the Political Economy of Storage

In Mesopotamia, grain was never a neutral commodity. It functioned simultaneously as food, currency, tax, wage, and political instrument. Control over grain storage and distribution allowed institutions to translate agricultural surplus into authority. Temples and palaces did not merely collect grain as passive recipients of tribute. They organized, measured, recorded, and redistributed it in ways that structured the entire agrarian economy.

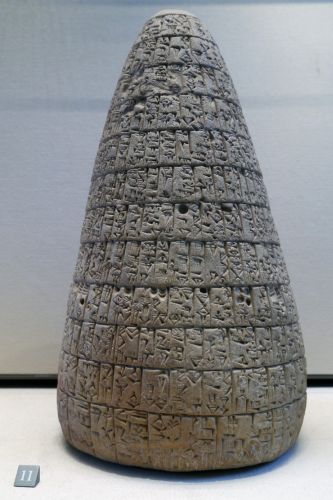

Large institutional storehouses dominated the landscape of early cities. Archaeological remains and administrative tablets reveal complex systems of intake, storage, and allocation managed by scribes and officials. Grain flowed into these centers through taxes, rents, and obligatory deliveries tied to land tenure or labor service. Once inside institutional control, it ceased to belong to individual producers in any meaningful sense. Access to stored grain was conditional, mediated by status, obligation, and favor.

This system offered genuine advantages during periods of stability. Centralized storage reduced spoilage, facilitated redistribution, and supported large-scale projects such as temple construction, irrigation maintenance, and military mobilization. Rations issued from temple and palace stores sustained dependent laborers and reinforced institutional loyalty. In this sense, grain storage underwrote state capacity itself. It enabled coordination across time and space that no individual household could achieve.

Yet these same mechanisms created asymmetries that favored institutions over smallholders. When harvests were strong, surplus flowed upward. When harvests failed, dependence flowed downward. Temples and palaces could release grain selectively, often at fixed or administratively determined rates that ignored market distress. What appeared as benevolent redistribution was inseparable from political leverage. Access to grain became a tool for enforcing compliance and deepening dependency.

Price dynamics further amplified institutional advantage. While markets existed, they operated within boundaries shaped by institutional stockpiles. In times of shortage, temples and palaces could influence prices simply by withholding or releasing grain. Smallholders, lacking reserves, were forced to buy at inflated rates or borrow against future harvests. In effect, centralized storage converted ecological volatility into economic pressure that institutions were uniquely positioned to survive and exploit.

The political economy of storage transformed grain into an architecture of power. Control over food meant control over labor, land, and ultimately social stability. The system did not require overt coercion to function. Its logic was embedded in accounting practices, legal norms, and everyday survival. By monopolizing resilience, temples and palaces ensured that vulnerability remained a household problem rather than a systemic concern, laying the groundwork for recurring cycles of indebtedness and dispossession.

Debt, Credit, and the Machinery of Dispossession

Credit in ancient Mesopotamia was not a marginal or exceptional feature of agrarian life. It was a structural necessity within a system that offered little tolerance for disruption. Grain and silver loans appear throughout the documentary record, extended to farmers facing shortfalls caused by failed harvests, delayed floods, or institutional extraction. These loans were often framed as temporary relief, yet their terms reflected a legal order that prioritized repayment over subsistence. Obligation endured regardless of circumstance.

The mechanics of debt transformed ecological misfortune into legal vulnerability. Loans denominated in grain or calculated in silver equivalents carried fixed repayment expectations that did not adjust to environmental realities. Interest, whether explicit or embedded in repayment ratios, compounded the burden. When repayment deadlines arrived and households could not meet them, default triggered predictable consequences. Land, labor, or family members themselves could be seized or pledged, not as extraordinary punishment but as routine enforcement of contract.

Legal codes normalized these outcomes. Surviving laws from the Old Babylonian period demonstrate that foreclosure, debt bondage, and land transfer were not signs of systemic failure but of systemic operation. Creditors, often wealthy individuals or institutions, acquired fields through legal means that preserved the appearance of order while hollowing out the smallholder class. Dispossession proceeded through courts and contracts rather than violence, making it both durable and difficult to contest.

Debt gradually functioned less as a temporary bridge and more as a conveyor belt moving land and autonomy upward. Smallholders did not lose farms because they misunderstood risk or mismanaged resources. They lost them because the system converted survival borrowing into permanent loss. Credit, framed as assistance, became the primary machinery through which agrarian independence was dismantled, ensuring that consolidation occurred incrementally, legally, and with minimal disruption to institutional authority.

From Crisis to Consolidation: How Small Farms Disappeared

Repeated crises did not merely interrupt agrarian life in Mesopotamia. They reshaped it. Each episode of crop failure, price fluctuation, or administrative extraction initiated a familiar sequence in which smallholders borrowed to survive, defaulted when conditions failed to improve, and surrendered land as repayment. These individual losses accumulated into broad patterns of consolidation. What appeared in records as discrete transactions amounted, in aggregate, to the steady disappearance of family farms.

Institutional landholdings expanded as a direct consequence of this process. Temples and palaces absorbed fields not through conquest but through foreclosure and reassignment. Wealthy creditors, often connected to administrative or religious elites, similarly accumulated land by exploiting their access to credit and grain reserves. The landscape of cultivation shifted from a mosaic of household plots to increasingly concentrated estates worked by dependents rather than proprietors. This transformation altered not only ownership patterns but also social relations embedded in agricultural labor.

Consolidation carried political costs. As independent smallholders vanished, so too did the social base that supported civic stability. Former landowners became tenants, laborers, or debt dependents, their autonomy replaced by obligation. The concentration of land reduced incentives for long-term stewardship among dispossessed farmers while increasing the burden on institutions to manage production and distribution. The state gained scale but lost resilience, trading diversity for control.

This trajectory was neither accidental nor self-correcting. The mechanisms that drove consolidation were embedded in legal norms, credit practices, and administrative priorities. Without intervention, each crisis intensified the next by narrowing the pool of independent producers. Consolidation emerged as the predictable outcome of a system that allowed short-term survival strategies to generate long-term structural imbalance, eroding the agrarian foundation upon which Mesopotamian states depended.

Debt Jubilees and State Intervention: Emergency Repairs to a Broken System

Mesopotamian rulers were not blind to the dangers posed by unchecked consolidation. The documentary record preserves repeated royal edicts canceling debts, restoring land, and releasing individuals from bondage. These proclamations, often issued at the beginning of a reign or during moments of acute crisis, reveal a clear recognition that normal economic operations threatened the survival of the state itself. Debt jubilees were not expressions of generosity. They were acts of political triage.

Such interventions acknowledged a structural contradiction at the heart of Mesopotamian political economy. The same systems that enabled extraction, storage, and institutional stability also destroyed the smallholder base upon which production depended. When too many households lost land and autonomy, tax revenues declined, military manpower shrank, and social unrest intensified. Jubilees functioned as resets, temporarily reversing consolidation to reconstitute an agrarian class capable of sustaining the state.

The content of these edicts underscores their practical intent. Debt cancellations targeted personal obligations tied to grain and silver loans, returned seized land, and freed debt-bound laborers. They did not abolish credit systems or dismantle institutional estates. Instead, they selectively unwound their most destabilizing consequences. By restoring smallholders to their fields, rulers sought to revive agricultural output and reestablish a semblance of balance between institutions and households.

Yet the very repetition of jubilees exposes their limits. Each remission addressed the symptoms of crisis without altering the underlying mechanisms that produced it. Once normal legal and economic processes resumed, vulnerability reasserted itself. Smallholders again faced narrow margins, ecological risk, and exposure to debt. Consolidation slowly recommenced until the next intervention became necessary. Jubilees were cyclical not because rulers lacked insight, but because the political cost of deeper structural reform was prohibitive.

State intervention in Mesopotamia oscillated between restraint and reliance on the same systems that generated instability. Jubilees preserved order without challenging hierarchy. They prevented collapse while leaving the architecture of vulnerability intact. This pattern reveals a central lesson of early statecraft: when economic systems systematically erode their own social foundations, emergency repair becomes routine, and stability depends less on justice than on periodic suspension of the rules themselves.

Structural Parallels: Tariffs, Trade Disruptions, and Modern Small Producers

The economic pressures that undermined smallholders in ancient Mesopotamia are not confined to distant antiquity. Modern agricultural systems reproduce similar vulnerabilities whenever policy shocks disrupt prices, inputs, or access to markets. Tariffs, trade embargoes, and sudden regulatory shifts function much like ancient disruptions to grain flows: they alter conditions faster than small producers can adapt. The result is not evenly distributed pain, but asymmetric damage concentrated at the lowest margin of resilience.

Contemporary small farmers operate under constraints strikingly similar to their ancient counterparts. High fixed costs, dependence on seasonal cycles, and limited cash reserves leave little room for error. When tariffs raise input prices, restrict export markets, or provoke retaliatory measures, small producers absorb the shock immediately. Large agribusiness firms, by contrast, hedge risk across regions, negotiate favorable contracts, and draw on capital buffers that insulate them from short-term volatility. As in Mesopotamia, scale translates into survivability.

Trade disruptions also reshape credit dynamics. Price instability increases reliance on borrowing to cover operating costs, while declining revenues weaken repayment capacity. Financial institutions respond rationally by tightening terms or seizing collateral. Land consolidation follows, not because small farmers misjudge markets, but because structural exposure converts temporary shocks into permanent loss. What ancient grain loans accomplished through legal foreclosure, modern finance achieves through mortgages, liens, and debt restructuring.

State responses often mirror ancient jubilees in form if not in name. Emergency subsidies, loan forbearance, and targeted relief programs are deployed to prevent widespread collapse. These measures stabilize production in the short term but rarely address the deeper imbalance between small producers and consolidated actors. As relief expires, market pressures resume, and consolidation continues. Intervention becomes episodic rather than transformative, preserving output while allowing structural erosion to proceed.

The parallel is not metaphorical but functional. Both ancient and modern systems externalize risk onto small producers while concentrating resilience within institutions. Tariffs, like grain disruptions, do not initiate consolidation but accelerate it. Unless policy explicitly prioritizes the preservation of small-scale producers, crises will continue to redistribute land, capital, and power upward. History suggests that without decisive structural correction, emergency measures merely delay outcomes already built into the system.

Continuity, Not Coincidence: Why the Pattern Repeats

The recurring collapse of small producers across historical contexts is not the result of poor decision-making or cultural failure. It reflects structural conditions that consistently privilege scale, liquidity, and institutional durability over household resilience. In both ancient and modern systems, markets reward those who can absorb shocks, delay losses, and leverage credit. Smallholders, operating close to subsistence or narrow profit margins, lack these advantages. When disruption occurs, outcomes are shaped less by effort than by position within the economic architecture.

Markets alone do not correct this imbalance. On the contrary, they tend to intensify it. Price volatility, input shocks, and demand fluctuations disproportionately affect actors with limited buffers. Repeated exposure transforms temporary hardship into permanent loss. Consolidation is not an aberration but a logical outcome of systems that treat vulnerability as an individual problem rather than a collective risk. Without intervention, the disappearance of small producers is not a question of if, but when.

State intervention often acknowledges this reality implicitly while resisting its full implications. Emergency measures are introduced to prevent collapse, unrest, or supply disruption, yet they are framed as exceptional rather than structural. This framing preserves the legitimacy of existing arrangements while postponing deeper reform. As in ancient Mesopotamia, rulers and policymakers recognize the danger of excessive consolidation but remain constrained by political alliances, institutional inertia, and the perceived costs of altering foundational economic rules.

The persistence of this pattern across millennia suggests continuity rather than coincidence. Systems that concentrate resilience while dispersing risk generate predictable outcomes regardless of era or technology. The lesson is not that collapse is inevitable, but that prevention requires deliberate structural choices. History demonstrates that without sustained commitment to protecting small producers as a class, emergency intervention becomes cyclical, consolidation accelerates, and societies repeatedly confront crises of their own design.

Conclusion: Ancient Warnings and Modern Consequences

The agrarian history of ancient Mesopotamia offers one of the earliest and clearest demonstrations that economic collapse among small producers is rarely accidental. It emerges from systems that combine narrow margins, centralized control of surplus, and legal mechanisms that transform short-term survival strategies into permanent loss. Smallholders did not fail because they lacked discipline or foresight. They failed because the structures governing grain, credit, and obligation were designed to absorb shock upward while transmitting risk downward.

Debt jubilees reveal that Mesopotamian rulers understood this danger with remarkable clarity. Their repeated interventions acknowledged that unchecked consolidation threatened not only households but the stability of the state itself. Yet these measures also expose the limits of emergency governance. By suspending consequences without dismantling their causes, jubilees preserved order while ensuring that the same crises would recur. Stability was maintained through periodic interruption rather than structural reform.

The parallels to modern agrarian systems are neither superficial nor coincidental. Contemporary trade disruptions, tariffs, and market volatility reproduce ancient dynamics whenever small producers are left to absorb systemic risk alone. Emergency subsidies and relief programs function as modern equivalents of debt remission, mitigating immediate damage without altering the underlying distribution of vulnerability. Consolidation proceeds not despite intervention, but alongside it, reshaping rural economies and concentrating power in fewer hands.

History’s warning is not simply descriptive but prescriptive. Societies that rely on small producers cannot treat their collapse as a private failure without undermining their own foundations. The Mesopotamian record demonstrates that when resilience is monopolized and risk is individualized, crisis becomes cyclical and consolidation inevitable. If ancient states struggled to escape this pattern, modern societies, with far greater analytical tools and policy capacity, cannot claim ignorance. The consequences of inaction are not unknown. They are among the oldest lessons political economy has to offer.

Bibliography

- Adams, Robert McC. The Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Chicago: Aldine, 1966.

- —-. Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Algaze, Guillermo. Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Chen, Xie. “The Role of Modern Agricultural Technologies in Improving Agricultural Productivity and Land Use Efficiency.” Frontiers in Plant Science 16 (2025).

- Clapp, Jennifer. Food. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020.

- Ehret, Christopher. “Agricultural Origins: What Linguistic Evidence Reveals.” In The Cambridge World History, Vol. 2, edited by Norman Yoffee, 55-92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Englund, Robert K. “Administrative Timekeeping in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 31:2 (1988): 121–185.

- Eyre, Christopher J. “The Agricultural Cycle, Farming, and Water Management in the Ancient Near East. In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, edited by Jack Sasson. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1995.

- Garfinkle, Steven J. “Shepherds, Merchants, and Credit: Some Observations on Lending Practices in Ur III Mesopotamia.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 47:1 (2004): 1-30.

- Hudson, Michael. …and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year. Dresden: ISLET, 2018.

- —-. “Reconstructing the Origins of Interest-Bearing Debt.” In Debt and Economic Renewal in the Ancient Near East, edited by Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch, 7–58. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2002.

- —-. “The Role of Accounting in Civilization’s Economic Takeoff.” In Creating Economic Order, edited by Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch, 37–66. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2004.

- Hudson, Michael, and Marc Van de Mieroop, eds. Debt and Economic Renewal in the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2002.

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital and Ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press, 1944.

- Postgate, J. N. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Renger, Johannes M. “Institutional, Communal, and Individual Ownership or Possession Institutional, Communal, and Individual Ownership or Possession of Arable Land in Ancient Mesopotamia from the End of the Fourth to the End of the First Millennium B.C.” Chicago-Kent Law Review 71:1,11 (1995): 269-319.

- Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. 2nd ed. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.

- Scott, James C. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

- —-. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited. New York: W. W. Norton, 2017.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- —-. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- —-. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

- Wilkinson, Tony J. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. New York: Random House, 2010.

- Yoffee, Norman. Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.17.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.