The gladiatorial ludus reveals how violence can be stabilized through institutional design rather than sustained through constant improvisation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Violence as Institution, Not Accident

Gladiatorial combat in the Roman world is often treated as a spectacle of cruelty, a lurid expression of imperial decadence or popular bloodlust. Ancient critics and modern observers alike have emphasized the brutality of the arena, presenting it as evidence of a civilization numbed to suffering. These interpretations, while not entirely unfounded, risk isolating violence from the institutional frameworks that sustained it. The arena was not an eruption of chaos within an otherwise ordered society, nor was it merely the indulgence of a sadistic populace. It was a product of Roman administrative capacity, economic investment, and social organization. Beneath the sand and spectacle lay a system carefully structured to train bodies, discipline behavior, and generate repeatable performance. To understand the gladiator merely as a victim of brutality is to miss the more unsettling reality that Roman violence was administered through institutions designed to manage and normalize it, rendering what might otherwise appear exceptional into a predictable feature of civic life.

The gladiatorial school, or Ludus Magnus (the ludus), functioned not as a holding pen for condemned men but as an organized environment of conditioning. Recruitment, confinement, diet, training, surveillance, and ritual were not incidental features; they were structural components. Enslaved persons, prisoners of war, and condemned criminals entered an architecture that reshaped their identities into economic assets. Their bodies were regulated, their movements standardized, and their daily lives subjected to discipline calibrated for public performance. Violence in this context was not spontaneous aggression but rehearsed display, produced through deliberate institutional design.

This design extended beyond the individual gladiator to the rhythms of Roman civic life. Spectacle was embedded within political celebration, imperial generosity, and urban identity. The arena was funded, scheduled, and ritualized with precision. Crowds gathered not merely to witness death but to participate in a civic drama that rendered violence legible and socially sanctioned. The conditioning effected within the ludus intersected with a broader conditioning of spectators, who learned to interpret controlled brutality as entertainment, justice, and even honor. The institution shaped both performer and audience through structured repetition.

To examine the gladiatorial system as an institution rather than an accident is to shift the focus from isolated acts of cruelty to the architecture that made those acts routine. The Roman Empire did not tolerate the arena as a marginal aberration. It invested in it, regulated it, and integrated it into the ceremonial calendar of public life. Lanistae calculated costs and risks, magistrates financed games for political advancement, and emperors deployed spectacle as a demonstration of authority and largesse. The stability of gladiatorial combat depended on predictable training regimens, managed mortality rates, economic calculation, and ideological framing that cast violence as discipline, valor, or divine favor. Violence endured not because it was uncontrolled, but because it was organized within a system capable of reproducing itself. Understanding the ludus as a designed environment reveals how power can shape human behavior through structure, producing dependency and normalization without requiring constant coercive improvisation.

Recruitment and Vulnerability: Who Entered the Ludus

The population of the ludus was not random. Gladiatorial schools drew from groups already marked by legal and social vulnerability within Roman society. Many gladiators were enslaved persons captured in war, purchased through slave markets, or born into servitude. Others were condemned criminals, sentenced damnatio ad ludum as a form of punitive spectacle. A smaller but visible number were volunteers, the auctorati, who contracted themselves into gladiatorial service in exchange for payment or the hope of fame. Despite differences in origin, what united these entrants was a diminished autonomy at the moment of recruitment. Entry into the ludus signified not merely a change of occupation but a fundamental reclassification of the body as property or pledged collateral within a commercial enterprise.

War captives formed a significant reservoir of recruits, especially during periods of expansion in the Republic and early Empire. These individuals were uprooted from their communities and inserted into Roman systems of labor exploitation. In the case of the ludus, their physical strength and youth increased their market value. Age mattered. A gladiator represented a long-term investment, and lanistae sought men whose bodies could be trained, disciplined, and preserved for multiple performances. Youthfulness was not incidental; it was economically rational. The earlier the conditioning began, the more completely the institution could reshape identity and habit.

Condemned criminals entered under different legal circumstances but faced similar structural realities. Damnatio ad ludum sentences transformed punishment into commodified display. The criminal body became an instrument of entertainment, its fate absorbed into the rhythms of the games. Even here, selection was not arbitrary. Physical capability and spectacle value influenced placement. Roman penal policy intersected with economic calculation. The arena converted legal marginality into revenue, binding punitive authority to market logic. The individual’s prior crime became secondary to his utility within the institutional machinery of spectacle.

The case of the auctoratus complicates the picture but does not dissolve the pattern of vulnerability. Volunteers technically chose entry, often driven by debt, social marginalization, or the lure of prize money and recognition. Yet the contract they swore subjected them to corporal punishment, confinement, and potential death. The sacramentum they pronounced acknowledged total submission to discipline, including the acceptance of beating, burning, binding, and killing if ordered. By entering the ludus, the auctoratus surrendered civic dignity and placed his body under the absolute authority of the lanista. The law recognized this transformation. A free man who contracted as a gladiator incurred social infamia, a stain upon status that marked him as dishonored. What appeared outwardly as agency functioned within a constrained field of options shaped by economic distress or social ambition. The institution offered money and potential glory, but only through the internalization of obedience and the acceptance of institutional control. Voluntarism did not eliminate dependency; it formalized it within a contractual framework that converted precarious autonomy into disciplined subordination.

Recruitment via these pathways into the ludus operated through a convergence of vulnerability, youth, and economic valuation. Enslavement, condemnation, or debt narrowed alternatives. The institution did not create vulnerability from nothing, but it capitalized on it, consolidating disparate forms of marginality into a unified system of conditioning. Entry severed prior affiliations and replaced them with structured regimentation under the authority of the lanista. In this way, the gladiatorial school functioned as a mechanism of social conversion, transforming exposed populations into disciplined performers whose survival depended upon compliance within a carefully managed environment.

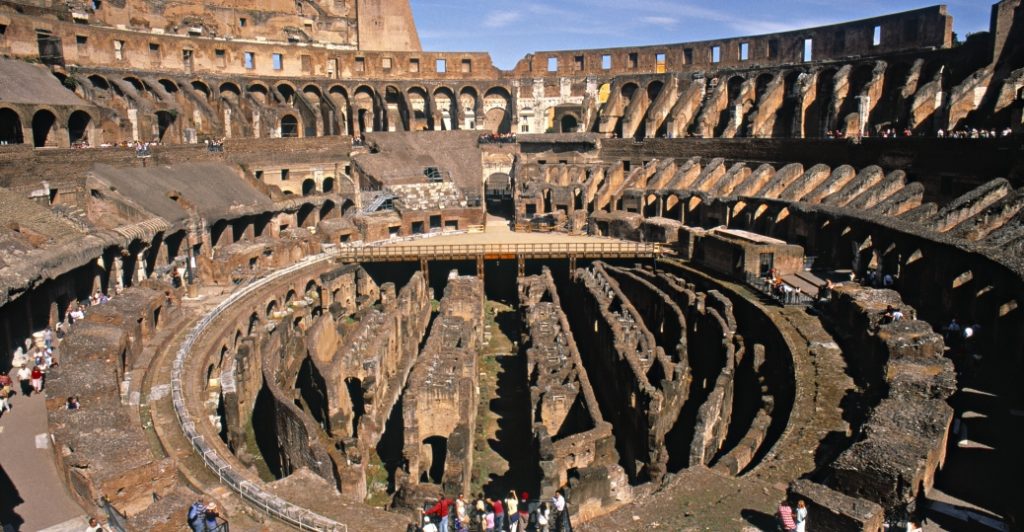

The Architecture of the Ludus: Isolation, Discipline, and Control

The physical structure of the ludus was integral to its function as an institution of conditioning. Gladiatorial schools were typically organized around enclosed courtyards surrounded by barracks, training grounds, and administrative quarters. The design facilitated surveillance and restricted movement, allowing instructors and overseers to monitor bodies in motion and bodies at rest. Gladiators lived in close quarters, often housed in small cells that limited privacy and reinforced separation from the wider urban community. Confinement was not merely punitive; it was formative. By controlling space, the institution controlled association, routine, and identity. Walls and gates created a boundary not only between gladiators and the city but between former selves and newly imposed roles. The built environment reduced external attachments and replaced them with a regimented internal order in which every movement occurred within the parameters of institutional oversight.

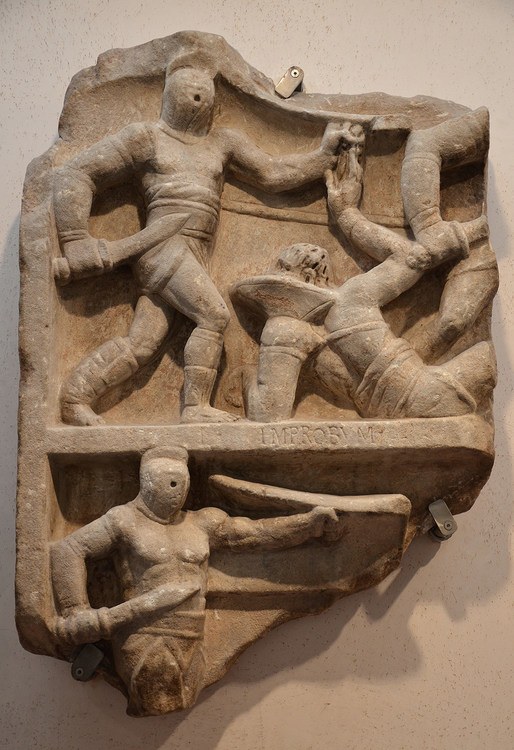

Within this spatial enclosure, daily life followed a disciplined rhythm. Training sessions were systematic and repetitive, emphasizing the mastery of specific combat styles associated with particular gladiatorial types. Wooden practice weapons and posts allowed for the standardization of movement before live combat. Instructors drilled fighters in technique, stamina, and endurance. Repetition was essential. Through constant rehearsal, the body absorbed patterns of motion that could be reproduced under the pressure of public spectacle. The goal was not improvisation but reliability. The institution sought to produce combatants whose actions could be anticipated, shaped, and refined for audience consumption.

Diet formed another critical component of this architecture. Gladiators were famously sustained on a high-calorie, grain-based regimen designed to build mass and resilience. Modern analysis of skeletal remains confirms a diet rich in barley and legumes, supplemented to strengthen bone density and aid recovery. Nutrition was calibrated to the demands of the arena. The body became a managed resource. Physical conditioning, injury treatment, and recovery were supervised not out of humanitarian concern but because the gladiator represented capital investment. Care and coercion coexisted within the same institutional logic.

Discipline extended beyond bodily training to encompass psychological regulation. The authority of the lanista was near absolute within the confines of the school. Punishment for disobedience could be severe, reinforcing hierarchies and discouraging dissent. At the same time, hierarchy among the gladiators themselves structured competition and aspiration. Experienced fighters could achieve prestige within the barracks, becoming exemplars for novices. This internal stratification fostered compliance by embedding ambition within the system. Advancement depended on mastery and obedience rather than resistance.

Isolation from the broader civic world intensified dependency. Although gladiators performed before massive audiences, their daily existence was circumscribed by institutional boundaries. External relationships were limited, and movement beyond the school was tightly controlled. This separation severed previous social ties and discouraged collective organization outside institutional oversight. Even camaraderie among gladiators operated within a controlled framework that emphasized loyalty to the training system rather than solidarity against it. The very rhythms of the day, from rising to training to rest, were regulated internally. This isolation narrowed the horizon of possibility. The institution became the primary site of recognition, reward, and survival. In the absence of alternative social anchors, the gladiator’s sense of identity increasingly aligned with the role the ludus had crafted for him.

Through the convergence of confinement, repetition, calibrated nutrition, hierarchical discipline, and controlled association, the architecture of the ludus produced predictable performers. Violence emerged not from uncontrolled impulse but from regulated training within a managed environment. The institution did not simply prepare men to fight; it structured their lives so thoroughly that fighting became the central axis of identity and survival. Predictability was itself a form of power. Lanistae and sponsors could calculate risk, anticipate outcomes, and stage contests that balanced danger with continuity. The arena depended upon the invisible labor of institutional design. By embedding control within space, routine, and hierarchy, the ludus transformed vulnerable individuals into instruments of spectacle through sustained, systemic regulation rather than episodic coercion.

Reward and Honor: The Psychological Feedback Loop

Coercion alone cannot explain the endurance of the gladiatorial system. The ludus relied not only on confinement and discipline but on a carefully structured set of rewards that transformed survival into aspiration. Success in the arena brought prizes, monetary awards, improved rations, and in rare cases the possibility of manumission symbolized by the wooden sword, the rudis. These tangible incentives were accompanied by less material but equally potent forms of recognition. Public acclaim offered an additional currency. Names of celebrated fighters circulated in graffiti, mosaics, and commemorative inscriptions, embedding their reputations within the urban landscape. Fame mitigated stigma, allowing even enslaved men to achieve a form of recognition otherwise denied to them in Roman society. The institution paired constraint with incentive, binding obedience to the promise of advancement and reframing danger as opportunity within a tightly controlled structure.

The ritual framework of gladiatorial life reinforced this dynamic. Upon entering service, the gladiator swore the sacramentum, an oath committing him to endure punishment, bondage, and even death. This ritual did more than formalize submission; it embedded discipline within a moral vocabulary of endurance and honor. To survive and perform well became proof of fortitude. Roman cultural ideals of virtus and courage were projected onto men whose legal status remained degraded. The institution appropriated elite values and repurposed them within a coercive structure, encouraging internalization of a role that fused subordination with valor.

Public performance intensified the feedback loop. Applause, gestures of approval, and the possibility of reprieve in moments of defeat placed the crowd in a position of evaluative authority. The audience did not merely witness violence; it conferred legitimacy. A gladiator who fought bravely could earn admiration even in death. This conditional approval encouraged risk-taking and loyalty to the spectacle itself. The desire for recognition linked personal survival to public expectation. The arena became not simply a site of danger but a stage upon which identity was affirmed through visible courage.

The ludus converted vulnerability into motivated participation. Rewards were uneven and contingent, yet their very uncertainty heightened their power. A single victory could transform status within the barracks. A string of successes might bring material gain or symbolic prestige. The institution did not eliminate fear, but it harnessed ambition. By coupling coercive discipline with structured incentives, the gladiatorial system sustained compliance through a psychological architecture that blended honor, hope, and dependency. Violence persisted not solely because men were forced to fight, but because the institution offered recognition as the price of survival.

Spectacle as Public Conditioning

The gladiatorial games were not merely the culmination of training within the ludus; they were the public interface of a broader system of social conditioning. Held in amphitheaters that dominated urban landscapes, the games transformed individual combat into civic ritual staged before tens of thousands. Attendance was not limited to elites. Citizens across social strata gathered to witness structured violence framed as celebration, commemoration, religious observance, or imperial generosity. The repetition of these events habituated audiences to a particular visual grammar of bloodshed in which danger was stylized and mortality rendered comprehensible. Violence was choreographed, rule-bound, and integrated into the ceremonial calendar, often tied to festivals, triumphs, or funerary honors. What might otherwise provoke moral shock became normalized through predictable recurrence. The arena did not erupt unpredictably into Roman life; it punctuated it with regularity, reinforcing the expectation that organized combat was a legitimate and even necessary feature of civic experience.

Political authority played a decisive role in this normalization. Magistrates financed games to advance careers, and emperors sponsored lavish spectacles to demonstrate munificence. The distribution of seats reinforced hierarchy, arranging the crowd according to status while uniting them in shared observation. Spectacle fused political patronage with collective experience. The arena offered rulers an opportunity to display control over life and death before a captive audience. By embedding combat within official ceremony, the state rendered organized violence not only acceptable but constitutive of civic identity.

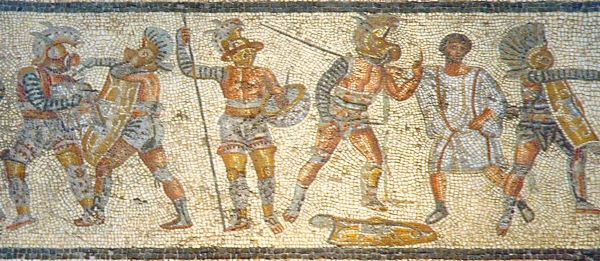

The structure of the games further reinforced conditioning through ritualized expectation. Combat followed established pairings and typologies, each with recognizable armor, weaponry, and narrative logic. Spectators learned to interpret these signals, anticipating styles of engagement and probable outcomes based on visual cues alone. A murmillo signaled one kind of encounter, a retiarius another, and the contrast between their equipment shaped the drama before a single blow was struck. The crowd’s responses were not random but informed by shared conventions and accumulated experience. Gestures of approval or disapproval, cries for mercy, and reactions to decisive blows formed part of the choreography. Through participation, audiences internalized the rules that governed the spectacle. Violence became intelligible and manageable within a communal framework, its unpredictability contained within familiar narrative boundaries.

This conditioning extended to moral interpretation. Gladiatorial combat was often framed as a demonstration of courage, endurance, and discipline, virtues central to Roman self-understanding. Even in defeat, a fighter who displayed composure could be honored, and a dignified death might elicit admiration rather than horror. The emphasis on valor obscured the coercive structures that produced the combatant in the first place. By focusing attention on performance rather than recruitment, confinement, or contractual submission, the spectacle redirected scrutiny away from institutional architecture. The crowd saw bravery, not barracks; skill, not surveillance; honor, not isolation. Public admiration reinforced the legitimacy of the system by privileging visible action over hidden conditioning, transforming systemic coercion into an arena for moral display.

The repetition of spectacle gradually cultivated desensitization. Exposure to staged violence at regular intervals reduced the novelty of bloodshed. What was once extraordinary became customary. The amphitheater functioned as a pedagogical space in which citizens learned to interpret suffering through the lens of entertainment and civic ritual. Emotional responses were guided by collective cues. Applause, silence, or outrage followed patterns shaped by precedent. In this way, the arena did not simply reflect Roman attitudes toward violence; it actively shaped them.

The conditioning effect of spectacle operated on two levels. Within the ludus, bodies were trained for controlled performance. Within the amphitheater, audiences were trained to consume that performance as meaningful and legitimate. The durability of the gladiatorial system depended upon this reciprocal architecture. Performers internalized discipline in pursuit of reward, while spectators internalized acceptance through repeated exposure. The institution sustained itself by aligning private conditioning with public normalization, ensuring that organized violence remained embedded in the fabric of Roman civic life.

Economic Logic: The Ludus as Investment System

Behind the spectacle and ritual lay a clear economic rationale. The gladiatorial school operated as a business enterprise in which human bodies were treated as managed assets within a competitive urban marketplace. Lanistae purchased enslaved men, accepted condemned criminals, or contracted volunteers with the expectation of recurring financial return rather than immediate consumption. Training required substantial resources: food, medical care, specialized equipment, housing, and skilled instruction. Facilities had to be maintained, trainers compensated, and fighters kept in viable physical condition. These expenditures were justified only because a trained gladiator could be rented to sponsors, sold at profit, or repeatedly exhibited in games financed by magistrates and emperors. The arena’s drama depended on the prior stabilization of cost and risk within the ludus. Violence was profitable precisely because it was regulated, calculated, and embedded within a structure that transformed bodily vulnerability into predictable revenue streams.

Investment logic shaped recruitment and preservation alike. A gladiator who died too quickly represented a loss. Contrary to popular imagination, many contests were structured to maximize spectacle while limiting unnecessary fatalities. Experienced fighters carried reputational value that could draw crowds and command higher fees. Their survival enhanced the long-term profitability of the school. Training aimed not simply at lethality but at controlled performance. The lanista balanced danger against durability, calibrating combat to sustain both drama and return on investment.

The commodification extended beyond individual fighters to the branding of gladiatorial types. Armor, weaponry, and stylized combat pairings created recognizable categories that could be marketed and anticipated by spectators familiar with the conventions of the arena. The visual contrast between heavily armored and lightly equipped fighters generated narrative tension that could be replicated across events. Names of successful gladiators circulated widely, functioning as a form of advertisement that enhanced the prestige of a particular school. Inscriptions and graffiti attesting to popular favorites testify to a culture of consumer recognition in which spectators followed individual careers. The school operated within a broader entertainment economy in which reputation increased monetary value. A gladiator’s identity became inseparable from his exchange potential, and his body served simultaneously as performer, product, and promotional symbol within a structured commercial framework.

Economic calculation also intersected with political patronage. Sponsors of games contracted with lanistae to supply fighters for specific events, negotiating fees and conditions. The quality of the spectacle influenced public reception and, by extension, the sponsor’s standing. Financial investment by elites reinforced the institutional stability of the ludus. The profitability of the school was tied to the ambitions of magistrates and emperors seeking popular approval. Market logic and political strategy converged in the management of human combatants.

The ludus was not a chaotic repository of condemned men but a structured investment system embedded within Roman urban life. The conditioning of gladiators, the regulation of mortality, and the cultivation of reputation were all shaped by economic imperatives. Institutional design served profitability. The arena’s apparent spontaneity concealed an underlying network of contracts, calculations, and resource management. Violence endured because it could be organized, marketed, and sustained as a commercial enterprise supported by both private entrepreneurship and public demand.

Dependency without Illusion: Why the System Endured

The endurance of the gladiatorial system cannot be attributed solely to coercion, nor entirely to popular enthusiasm. Its durability rested upon a convergence of institutional design, economic incentive, and cultural normalization that left little room for structural challenge. Gladiators were dependent upon the ludus for survival, yet that dependency was neither concealed nor disguised as freedom. The oath they swore, the confinement they endured, and the public branding of their status made the hierarchy unmistakable. Roman society did not pretend that the gladiator was autonomous. Instead, it embedded his subordination within a framework that promised recognition and material sustenance in exchange for obedience. What sustained the institution was not deception but integration. Each component of the system reinforced the others, creating a closed circuit in which discipline, reward, spectacle, and profit stabilized one another. Dependency became durable because it was institutionalized rather than hidden.

For the gladiator, alternatives were sharply limited. Enslavement, condemnation, or debt narrowed avenues of exit. Even manumission did not fully erase stigma. The status of infamia lingered, marking former fighters as socially compromised. Within these constraints, compliance was rational. Advancement within the institution offered relative improvement over marginal existence beyond it. Dependency did not require ideological illusion. It operated through structured necessity. The design of the ludus ensured that survival, recognition, and material security were tethered to participation in the spectacle.

The Roman public, for its part, had little incentive to interrogate the system’s foundations. Spectacle was woven into civic identity and political expectation, appearing as an extension of tradition rather than a deviation from it. Games were associated with generosity, victory, religious observance, and communal celebration. Because the violence appeared disciplined and rule-bound, it could be interpreted as controlled rather than chaotic, bounded rather than anarchic. Institutional stability fostered moral distance. The audience consumed performance without confronting recruitment, confinement, or economic calculation. The barracks remained invisible; the contracts unseen. Acceptance was not passive ignorance but habituated recognition formed through repetition and ceremony. The games fit within an established cultural vocabulary that rendered them intelligible and legitimate, reinforcing the perception that organized violence belonged within the civic order.

The system endured because it aligned private dependency with public affirmation. Gladiators were conditioned to seek reward within the structure that constrained them. Spectators were conditioned to perceive that structure as normal and even honorable. Economic actors profited, political elites gained prestige, and the state reinforced authority through display. No single illusion sustained the arena. Rather, its longevity emerged from the interlocking architecture of confinement, incentive, spectacle, and profit. The ludus persisted because it functioned as an integrated institution, capable of reproducing both compliance and acceptance without continual reinvention.

Conclusion: Institutional Design and the Conditioning of Human Behavior

The gladiatorial ludus reveals how violence can be stabilized through institutional design rather than sustained through constant improvisation. Recruitment channeled vulnerable populations into controlled environments. Architecture confined and surveilled. Training standardized bodily movement. Incentives aligned ambition with obedience. Spectacle normalized performance before mass audiences. None of these elements functioned independently. Together they formed a coherent system that transformed marginalized men into predictable instruments of public display. The durability of the arena rested not on chaos but on coordination.

By examining the ludus as a structured institution, the focus shifts from individual cruelty to systemic architecture. Gladiators were not merely victims of arbitrary brutality; they were participants within a managed economy of risk and reward. Their dependency was produced through confinement, reinforced through discipline, and sustained through calibrated incentives. The system’s success lay in its ability to convert vulnerability into functionality. Institutional stability emerged from the careful alignment of spatial control, economic calculation, and cultural framing.

The arena likewise conditioned its spectators. Repetition habituated audiences to stylized violence. Ritual and hierarchy framed combat as civic celebration. Political sponsorship integrated spectacle into public life. The result was a reciprocal dynamic in which performers and observers were shaped by the same structure. Conditioning operated both behind the walls of the ludus and within the vast amphitheaters that anchored Roman cities. The institution reproduced acceptance as effectively as it reproduced combatants.

The history of the gladiatorial school demonstrates that human behavior can be directed not only through overt coercion but through environments designed to narrow alternatives and channel desire. The Roman Empire did not rely on constant force to sustain the arena. It relied on architecture, routine, incentive, and repetition. Institutional design rendered organized violence durable by embedding it within economic logic and civic expectation. In this convergence of discipline and spectacle, the ludus stands as a powerful example of how structured systems can condition both action and perception.

Bibliography

- Barton, Carlin A. The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Bradley, Keith R. Slavery and Society at Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Cowles, Lauren E. “The Spectacle of Bloodshed in Roman Society.” Constructing the Past 12:1,10 (2011), 12-16.

- Evans, George. “The Horrible Life of Gladiators: Revisionist History and the Violence of Roman Gladiatorial Games.” Vulcan Historical Review 20:19 (2016), 185-189.

- Futrell, Alison. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997.

- —-. The Roman Games: Historical Sources in Translation. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

- Harper, Kyle. Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Hopkins, Keith. “Murderous Games: Gladiatorial Contests in Ancient Rome.” History Today 33:6 (1983), 16–21.

- Junkelmann, Marcus. Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Minowa, Yuko and Terrence H. Witkowski. “Spectator Consumption Practices at the Roman Games.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 4:4 (2012), 510-531.

- Veyne, Paul. Bread and Circuses: Historical Sociology and Political Pluralism. Translated by Brian Pearce. London: Penguin Books, 1990.

- Wiedemann, Thomas E. J. Emperors and Gladiators. London: Routledge, 1992.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.18.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.