Engels and subsequent reformers played a decisive role in reframing industrial suffering as structural rather than incidental.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Opportunity as Industrial Rhetoric

The industrial transformation of nineteenth-century Britain was accompanied by a powerful narrative of progress that framed mechanization as both inevitable and beneficial. Factories were celebrated as engines of national wealth, technological ingenuity, and social mobility, symbols of a society advancing beyond agrarian constraint into modern productivity. Industrialists, political economists, and reform-minded commentators often described the factory as a site where discipline, regular wages, and technological innovation converged to elevate the working classes. Mechanized production was presented not as rupture but as rational evolution, a system that increased output, lowered costs, and expanded opportunity. Employment in mills and workshops, including that of women and children, was frequently defended as preferable to the instability of rural labor or the insecurity of domestic industry. In this rhetorical environment, the factory appeared as a ladder rather than a cage, a pathway toward economic participation in a rapidly expanding industrial nation.

This rhetoric of opportunity obscured the structural reorganization that factories imposed upon daily existence. Industrial production did not simply gather workers under one roof; it redefined time, discipline, and bodily movement at a fundamental level. The factory clock replaced seasonal rhythms and customary breaks, subjecting laborers to standardized hours regulated by machinery rather than by natural cycles. Bells signaled beginning and end, and punctuality became a moral as well as economic expectation. Regular wages, while promising stability, tethered survival to compliance with externally imposed schedules and production targets. Spatial arrangement concentrated supervision, allowing managers to monitor output and behavior continuously. By emphasizing wages, productivity, and national prosperity, defenders of the system shifted attention away from the lived experience of those subjected to this new regime. The claim that factories offered opportunity implicitly assumed that access to employment outweighed the costs of exhaustion, injury, and enforced dependency embedded within the industrial environment.

Children occupied a central place within this narrative. Their employment was frequently justified as training for industrious adulthood or as economic necessity for working families. Factory labor, it was argued, instilled discipline and skill while preventing moral decay associated with idleness. Such defenses framed child labor not as exploitation but as preparation. Yet the structured environment in which children worked was neither incidental nor temporary. Long hours, repetitive tasks, and constant supervision shaped habits and expectations at formative stages of life. Opportunity, in this context, functioned less as a neutral description and more as a moral shield for institutional design.

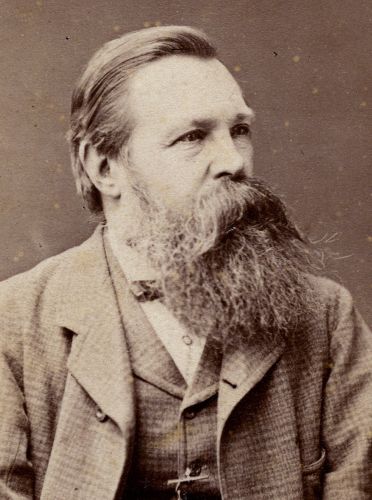

The question is not whether industrialists intended harm in a narrowly personal sense. Many framed their enterprises as socially beneficial and economically indispensable. Rather, the issue concerns whether the architecture of the factory system embedded foreseeable injury within its structure. Friedrich Engels and other reformers shifted the debate from individual cruelty to systemic organization, arguing that schedules, spatial arrangement, and wage dependency conditioned compliance and normalized exhaustion. By interrogating opportunity as rhetoric, one uncovers the deeper logic of industrial design, in which claims of progress coexisted with structural vulnerability.

The Architecture of the Factory: Time, Space, and Surveillance

The industrial factory was not merely a building that housed machinery; it was a deliberately structured environment that reorganized human activity around mechanical rhythm. Production no longer followed the irregular cadence of craft labor or agricultural seasons, where tasks were often completed according to daylight, weather, or negotiated pace. Instead, it conformed to the fixed tempo of powered machines whose operation demanded continuous attention. Time became abstract, measurable, and enforceable in ways that detached it from lived experience. The introduction of standardized shifts transformed labor into quantifiable units, aligning bodily movement with the uninterrupted rotation of gears and belts. Workers entered and exited according to bell signals rather than communal rhythms. The factory functioned as a spatial and temporal regime in which human endurance was calibrated to mechanical capacity, and where deviation from schedule carried economic and disciplinary consequences.

E. P. Thompson famously described this transformation as the emergence of “time-discipline,” a shift in which punctuality and regularity became moral imperatives rather than practical conveniences. Under the factory system, lateness could result in fines, dismissal, or public reprimand, embedding obedience to the clock within a regime of accountability. The abstraction of time severed labor from personal autonomy, subordinating it to externally imposed schedules that prioritized machine efficiency over bodily limits. Workers were no longer accountable primarily to the completion of a task judged sufficient by craft standards, but to continuous attendance measured against uniform hours. The clock imposed a new hierarchy in which time itself became employer. In this reconfiguration, compliance was not episodic but continuous, woven into the daily structure of work and reinforced by economic necessity.

Spatial organization reinforced this discipline. Machinery was arranged to maximize oversight and efficiency, often placing supervisors in elevated or central positions from which they could observe large portions of the workforce. Open factory floors reduced privacy and minimized unsupervised movement. The proximity of workers to one another was not designed for collaboration but for synchronization. Each individual’s motion became part of a larger mechanical choreography. Space, like time, was structured to facilitate predictability and minimize deviation.

Surveillance extended beyond mere visibility. Foremen and managers monitored pace, output, and demeanor, ensuring adherence to production targets. Records of attendance and productivity rendered performance legible in bureaucratic form. This documentation transformed individual labor into measurable data, reinforcing accountability to management rather than to craft standards. The constant possibility of observation shaped behavior even in the absence of direct intervention. Compliance became habitual, embedded within the awareness that deviation would be detected.

Repetition amplified these effects. Industrial tasks were frequently subdivided into narrow, monotonous actions repeated for hours with minimal variation. Such repetition reduced the scope for independent judgment and discouraged creative engagement with the labor process. Workers’ movements became routinized, conditioned to match the demands of machinery rather than personal discretion. Fatigue accumulated not only physically but cognitively, narrowing attention and limiting the capacity for sustained resistance. The convergence of long hours, mechanical pacing, and supervised repetition created an environment in which exhaustion was structurally predictable. Conditioning occurred not through overt coercion alone but through environmental design that gradually reshaped habit and expectation.

The factory system represented a form of institutional architecture that structured behavior through its material and temporal arrangements. The building itself, the arrangement of machinery, the regulation of hours, and the monitoring of output collectively formed a conditioning apparatus. Harm did not arise solely from isolated acts of cruelty; it was embedded in the configuration of production. By examining time, space, and surveillance as design elements, one sees how industrial modernity transformed labor into a system in which compliance and exhaustion were foreseeable outcomes of structural organization.

Child Labor and Malleability

Child labor occupied a central place in the early industrial factory system, not as a marginal supplement but as a structural component of production. Children were employed in textile mills, coal mines, and metal works in significant numbers, often beginning at remarkably young ages. In certain districts, entire family economies became dependent upon the wages of minors, binding household survival to industrial demand. Industrialists defended this practice as economically necessary and socially beneficial, arguing that factories provided steady income in regions destabilized by the decline of domestic industry. Wages earned by children were portrayed as vital contributions to family subsistence, while factory work was framed as an alternative to vagrancy, parish relief, or moral disorder. In public discourse, the image of the industrious child replaced that of the idle street wanderer. Employment was presented as formative discipline, aligning youthful energy with productive citizenship. Yet the systematic integration of children into industrial labor reveals a calculated reliance on their physical and social vulnerability, transforming economic necessity into institutional dependency.

Children were valued not only for lower wages but for their malleability. Smaller bodies could navigate tight machinery spaces, and their perceived adaptability made them easier to train in repetitive tasks. More importantly, they entered the factory at formative stages of psychological and physical development. Long hours under mechanical pacing normalized fatigue and obedience before alternative habits could take root. The early conditioning of attention, posture, and endurance shaped expectations about work and authority. Rather than merely participating in industrial production, children were socialized into its rhythms in ways that limited later autonomy.

Factory schedules intensified these effects. Shifts commonly extended well beyond ten hours, and in earlier decades could stretch considerably longer, especially before legislative intervention imposed limits. Breaks were minimal, often tightly regulated, and the monotony of tasks left little room for variation or creative engagement. The repetition of narrow movements under constant supervision shaped bodily habits that prioritized mechanical precision over personal discretion. Fatigue accumulated not only daily but developmentally, affecting growth, health, and cognitive resilience. Reports from Factory Commissions documented stunted bodies, chronic respiratory illness, spinal deformities, and exhaustion among young workers subjected to prolonged confinement in poorly ventilated environments. Such outcomes were not surprising anomalies but foreseeable consequences of aligning childhood development with industrial productivity. The factory environment did not merely employ children; it structured their physical maturation and psychological expectations around continuous output.

Moral defenses of child labor frequently invoked paternal language. Industrialists argued that factory discipline instilled punctuality, industriousness, and moral order. Work was said to prevent vice and cultivate character. This framing mirrored earlier justifications of hierarchical tutelage in other institutional settings. Yet discipline under mechanical supervision differed fundamentally from education in autonomy. The regimented environment of the factory left limited space for intellectual development or play. Conditioning replaced cultivation. The rhetoric of preparation masked the reality that industrial labor often constrained rather than expanded future possibilities.

Reformers such as Engels recognized that child labor revealed the structural logic of the factory system with particular clarity. In his analysis, the exploitation of children was not an unfortunate excess but evidence of how industrial capitalism organized labor around vulnerability and cost efficiency. Harm was not confined to isolated accidents or abusive overseers; it was embedded in the design of schedules, wages, and supervision that relied on youthful compliance. Because children lacked bargaining power and were dependent upon parental and employer authority, their labor could be intensified with minimal resistance. Their malleability made them especially suited to environments that prioritized repetition and endurance over self-determination. By examining child labor as a structural feature rather than a moral anomaly, one confronts the deeper reality that the factory system conditioned dependency at the earliest stages of life, embedding compliance within the developmental arc of industrial society.

Repetition, Fatigue, and the Engineering of Compliance

If the factory reorganized time and space, it also reshaped the body through repetition. Industrial production depended upon the subdivision of labor into narrowly defined tasks that could be performed continuously with minimal variation. Unlike craft work, which often required holistic skill, judgment, and periodic adjustment, factory labor reduced motion to repeatable sequences calibrated precisely to the demands of machinery. Workers became extensions of mechanical systems, their gestures synchronized with spinning frames, looms, stamping presses, and conveyor mechanisms. The logic of efficiency favored fragmentation: complex processes were broken into component movements so that each worker performed a single function at speed. This narrowing of activity did not simply increase output; it standardized behavior and constrained imagination. By limiting the range of motion, decision-making, and pacing required, the system diminished opportunities for autonomy within the labor process. Repetition became not only a technique of production but a mechanism of behavioral conditioning.

Repetition carried physiological consequences that were cumulative and predictable. Long hours of constrained movement strained muscles and joints, while exposure to industrial noise, airborne fibers, dust, and vibration compounded bodily stress. The unrelieved rhythm of machinery demanded sustained attention and precise timing, leaving little margin for rest or recalibration. Fatigue accumulated across shifts, reducing both physical stamina and cognitive alertness. In this state, resistance to managerial authority became less feasible, as exhaustion narrowed focus to immediate endurance. The predictability of fatigue was not incidental; it was structurally aligned with a production model that valued sustained output over individual well-being. When work is organized to demand continuous repetition at mechanical speed, bodily depletion becomes foreseeable rather than accidental. The architecture of labor made exhaustion an embedded feature of industrial efficiency.

Fatigue also had psychological effects. Monotonous tasks diminished intellectual engagement and fostered habituation. Workers trained to repeat single motions for extended periods were conditioned to subordinate initiative to rhythm. The internalization of pace replaced deliberation. This was not simply a matter of boredom; it was a restructuring of attentional patterns. The environment shaped expectations about authority and obedience. Compliance emerged not solely from explicit threats or punishment, but from habituated routine reinforced daily. The factory cultivated a form of disciplined passivity grounded in repetition.

Economic dependency reinforced this conditioning in ways that extended beyond the immediate factory floor. Regular wages tied subsistence to attendance and output, creating incentives to endure fatigue rather than challenge conditions. Absence, dismissal, or even minor disciplinary penalties could threaten immediate hardship, particularly in households reliant on multiple wage earners. The wage system functioned in tandem with repetitive labor to stabilize compliance. Workers might recognize strain or injustice, yet the risk of unemployment or wage loss constrained collective action. Dependency was not merely economic but structural, embedded in a system that linked bodily endurance to financial survival. The architecture of production aligned exhaustion with vulnerability, narrowing avenues for dissent and reinforcing routine acquiescence.

Engels observed these patterns not as isolated abuses but as systemic features of industrial organization. He linked recurring illness, shortened life expectancy, and chronic exhaustion to the design of factory labor itself. In his account, harm was embedded in the structural logic of production that prioritized efficiency and profit over human development. The repetition of motion and the accumulation of fatigue were not unfortunate side effects but foreseeable outcomes of a system engineered for continuous output. By emphasizing pattern over anecdote, Engels reframed the moral question: the issue was not whether particular overseers were cruel, but whether institutional design made compliance and injury inevitable.

The engineering of compliance through repetition and fatigue marked a conceptual turning point in debates over industrial labor. If harm could arise from the normal functioning of a system rather than from deviation or malice, then responsibility could not be confined to individual actors. It had to be located in architecture. The recognition that foreseeable injury might stem from design rather than intent laid groundwork for legislative intervention and regulatory reform. Repetition and fatigue, once defended as necessary features of efficiency, became evidence of structural imbalance. In this shift from individual fault to systemic accountability, the factory emerged not only as a site of production but as a laboratory for modern understandings of institutional harm.

Engels’s Intervention: From Moral Outrage to Structural Critique

Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England marked a decisive shift in how industrial labor was analyzed and judged. While earlier critics had condemned individual abuses or lamented visible misery, Engels sought to document patterns. His method combined firsthand observation in Manchester with statistical evidence, parliamentary reports, and economic analysis. The result was not a series of isolated moral complaints but a systemic indictment. Engels treated overcrowded housing, disease, child labor, and premature mortality not as accidental byproducts of modernization but as recurring features of industrial organization. By foregrounding repetition and regularity, he reframed suffering as structurally produced rather than episodic.

Engels rejected the prevailing defense that industrialists lacked malicious intent. He acknowledged that many factory owners considered themselves respectable men operating within competitive markets and often justified their practices as necessary for survival amid economic rivalry. Yet he argued that moral self-perception did not absolve structural responsibility. The pressures of profit maximization, fluctuating demand, and technological competition compelled employers to extend hours, reduce wages, and intensify production. Even if individual managers believed they were acting prudently rather than cruelly, the cumulative logic of the system generated predictable harm. Engels insisted that intent could not be the sole measure of accountability when institutional arrangements systematically produced exhaustion and deprivation. He redirected attention from personal character to economic architecture. The question was no longer whether a factory owner was benevolent or severe, but whether the competitive framework and spatial design of industrial production made exploitation an inherent and foreseeable outcome.

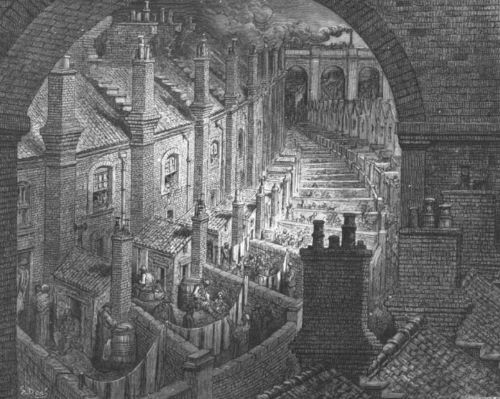

Important to Engels’s critique was the linkage between economic structure and social environment. He described working-class districts as segregated spaces shaped by industrial growth, where inadequate sanitation, polluted air, and overcrowded dwellings compounded the physical strain of factory labor. These neighborhoods were not incidental settlements but products of rapid urbanization driven by industrial expansion. The clustering of housing near mills reduced travel time but intensified exposure to smoke, waste, and disease. Engels observed how narrow streets, damp cellars, and insufficient drainage created conditions ripe for epidemics. These circumstances were not separate from the workplace; they were extensions of the same economic logic that prioritized output over welfare. Industrial wages determined housing options, and industrial schedules structured domestic life, leaving little time or energy for community engagement. By mapping these interconnections, Engels demonstrated that the factory system radiated outward, shaping entire communities and embedding vulnerability into the urban landscape. Structural harm was spatial as well as temporal, manifesting in both the factory floor and the surrounding environment.

Engels also advanced a class analysis that interpreted compliance as conditioned rather than freely chosen. He argued that the dependency of workers on wages constrained their capacity to resist, while repetitive labor habituated them to disciplined routine and acceptance of hierarchical authority. What appeared to observers as resignation or indifference often reflected the narrowing of alternatives within an economy that offered few viable means of subsistence outside industrial employment. Engels emphasized that material insecurity discouraged sustained opposition, as strikes or protest risked immediate hardship for entire families. In this framework, agency was neither denied nor romanticized; it was situated within structural constraints that shaped behavior. The factory system did not merely exploit labor; it molded expectations and normalized inequality through daily practice. Engels’s intervention expanded the moral vocabulary of industrial critique by insisting that exploitation could be embedded in normal operations, not merely in deviations from them.

The significance of Engels’s intervention lay in its conceptual reach. By articulating the factory system as a coherent structure that generated foreseeable harm, he contributed to a broader intellectual movement that redefined responsibility in industrial society. Structural critique shifted public debate toward regulation, inspection, and legislative reform. Although Engels wrote from a socialist perspective, his emphasis on institutional design resonated beyond partisan lines. The move from moral outrage at individual acts to analysis of systemic architecture became foundational to modern labor reform. In reframing industrial harm as structural rather than accidental, Engels helped prepare the ground for a new understanding of accountability in capitalist modernity.

Legal Recognition: The Factory Acts and Foreseeable Harm

The gradual passage of the Factory Acts in nineteenth-century Britain marked a turning point in the recognition of industrial harm as structural rather than accidental. Early resistance to regulation rested on the argument that state interference would disrupt economic growth and violate principles of free contract. Employers contended that labor agreements between factory owners and workers, including parents consenting to the employment of children, were voluntary arrangements. Harm, when acknowledged, was framed as exceptional or attributable to irresponsible individuals. Yet mounting evidence from parliamentary investigations and reform campaigns undermined this defense. Reports documented systematic overwork, injury, and stunted development among child laborers, revealing patterns that could not plausibly be dismissed as isolated incidents.

The Factory Act of 1833 represented a significant acknowledgment that the employment of children required structural limits. By restricting hours for younger workers and establishing a system of factory inspectors, Parliament implicitly recognized that harm flowed from the normal operation of industrial schedules. Subsequent legislation in 1844 and 1847 further reduced working hours and extended protections to women and adolescents. These reforms did not abolish industrial discipline, but they redefined the acceptable boundaries of production. The state’s involvement signaled an emerging understanding that competitive markets alone could not safeguard vulnerable populations when institutional design incentivized overextension.

Legal debates surrounding the Factory Acts increasingly centered on foreseeability. Reformers argued that excessive hours, inadequate ventilation, unsafe machinery, and relentless repetition produced predictable physical and moral consequences. The repetition of illness, injury, and early mortality across districts demonstrated that damage was systemic rather than episodic. Parliamentary testimony revealed recurring patterns of exhaustion and deformity among young workers, reinforcing the conclusion that harm was embedded in ordinary practice. Legislators began to accept that the absence of malicious intent did not absolve employers when injury resulted from routine organizational choices. The crucial shift lay in recognizing that competitive pressure and profit incentives could structure decisions in ways that made overwork and danger likely outcomes. Responsibility expanded beyond direct acts of cruelty to encompass the design of schedules, the allocation of supervision, and the pacing of machinery. Law increasingly acknowledged that when harm was foreseeable within a given institutional configuration, intervention was justified. In this transition, elements of the structural critique advanced by observers such as Engels entered legislative reasoning, even when expressed in pragmatic rather than revolutionary terms.

The recognition embodied in the Factory Acts established a precedent for modern regulatory governance. By intervening in hours, inspection, and safety, the British state acknowledged that institutional architecture could generate injury independent of individual intention. Regulation became a response not merely to moral scandal but to structural imbalance. The factory ceased to be understood solely as a private domain of contractual freedom and emerged as a site of public concern. In recognizing foreseeable harm embedded within design, nineteenth-century legislation laid foundations for subsequent labor protections and expanded the concept of accountability in industrial society.

The Conceptual Shift: From Intent to Architecture

The debates surrounding industrial labor in nineteenth-century Britain ultimately produced a deeper conceptual transformation. Early defenses of the factory system rested heavily on intent. Industrialists insisted that they did not wish to harm workers and that they merely operated within the competitive demands of a growing economy. Injury and exhaustion were described as unfortunate but incidental consequences of rapid modernization. Yet as evidence accumulated and reform gained traction, the moral framework began to change. The central question shifted from whether employers intended harm to whether the structure of production made harm predictable. This transition marked a profound reorientation in how responsibility was understood within industrial society.

Institutional architecture replaced personal motive as the primary site of analysis. Observers recognized that even well-intentioned actors could participate in systems that generated injury when incentives and structural pressures aligned in particular ways. Long hours, mechanical pacing, spatial concentration, and wage dependency combined to create conditions in which fatigue, illness, and shortened life expectancy were foreseeable outcomes of ordinary operations. The emphasis on architecture reframed harm as embedded rather than accidental, shifting attention from exceptional abuses to routine practice. Structural features that once appeared neutral, such as scheduling practices, supervision patterns, or machine arrangement, became objects of moral and legal scrutiny. Economic necessity no longer functioned as a sufficient defense when recurring patterns demonstrated predictable damage. Design choices, even if rational within competitive markets, carried consequences that extended beyond immediate profitability. By interrogating architecture rather than intent, reformers articulated a broader conception of accountability grounded in foreseeability and repetition.

This conceptual shift did not deny individual agency, but it contextualized it within systemic constraints. Employers retained decision-making power, yet those decisions were shaped by technological innovation, competitive rivalry, and profit imperatives that encouraged extended hours and intensified labor. Workers retained the capacity for resistance, yet their choices were constrained by wage dependency, household obligations, and cumulative fatigue. By analyzing the factory as a coherent system rather than a collection of isolated acts, reformers and legislators articulated a more complex model of accountability that acknowledged structural causation. Responsibility could extend to institutional configurations that channeled behavior in predictable directions and rewarded harmful efficiencies. The architecture of production became a site of ethical evaluation, not merely an economic arrangement. In recognizing that systems can produce injury even without explicit malice, nineteenth-century critics expanded the moral vocabulary of industrial society.

The move from intent to architecture laid groundwork for modern regulatory thought. It established the principle that structural design, when aligned with foreseeable harm, demands public scrutiny and potential intervention. Industrial Britain became an early laboratory for this reasoning, demonstrating that harm need not arise from explicit malice to warrant reform. In recognizing architecture as a source of injury, nineteenth-century debates expanded the boundaries of responsibility beyond individual conscience to encompass institutional design itself.

A Legacy of Structural Design in Contemporary Labor Systems

The conceptual shift from intent to architecture did not remain confined to nineteenth-century factories. Contemporary labor systems continue to demonstrate how institutional design shapes behavior, productivity, and vulnerability across sectors transformed by digital technology and global logistics. While steam engines and spinning frames have given way to automated warehouses, delivery platforms, and algorithmic coordination, the structuring of time, surveillance, and output remains central. Workers often encounter production environments in which pace is determined not by visible supervisors but by software calibrated to maximize efficiency. Algorithmic scheduling, dynamic routing, and performance scoring replicate earlier forms of time-discipline in technologically advanced form. Targets adjust in real time, and productivity benchmarks are continuously recalculated according to demand. As in the industrial factory, compliance is structured through the alignment of economic dependency with calibrated productivity metrics. The appearance of flexibility or innovation can obscure the persistence of institutional architectures that prioritize output while externalizing strain.

Digital management systems intensify surveillance in ways that echo and expand nineteenth-century oversight. Data collection renders worker activity continuously visible, transforming movement, keystrokes, and delivery times into quantifiable indicators. Performance dashboards replace ledger books, and automated warnings substitute for direct reprimands. The awareness of constant measurement encourages self-regulation. As with earlier factory discipline, surveillance does not require overt coercion to influence behavior; it conditions conduct through the knowledge that deviation is immediately detectable. Structural design, rather than explicit command, shapes daily experience.

Precarity also reinforces dependency in contemporary contexts. Gig labor platforms classify workers as independent contractors, framing flexibility as opportunity. Yet fluctuating demand, opaque algorithms, and incentive-based pay structures often tether income to sustained availability and rapid response. The rhetoric of autonomy parallels nineteenth-century claims that factory employment offered upward mobility. In both cases, economic necessity narrows meaningful choice. When access to income depends on constant connectivity or acceptance of unfavorable terms, compliance becomes structurally encouraged. The alignment of financial insecurity with algorithmic evaluation reproduces the dynamic in which foreseeability of harm arises from design rather than malice.

Modern regulatory debates reflect similar tensions between innovation and accountability, particularly as governments grapple with the legal status of platform-based labor and the scope of employer responsibility. Technology firms frequently argue that they merely provide neutral infrastructures for opportunity, distancing themselves from direct responsibility for working conditions or income instability. This framing mirrors earlier industrial defenses that emphasized voluntary participation and competitive necessity. Critics, drawing upon a lineage that includes nineteenth-century reformers, question whether structural features such as dynamic pricing, productivity quotas, constant tracking, and opaque evaluation systems generate predictable stress, inequality, and economic insecurity. Legal frameworks struggle to adapt, as classification disputes and labor protections lag behind technological change. The recurring question mirrors that of the nineteenth century: should responsibility attach only to explicit misconduct, or also to institutional architectures that make harm foreseeable? In this debate, architecture once again emerges as the critical analytical category.

The endurance of these debates underscores the lasting significance of the industrial era’s conceptual transformation. Recognizing harm as embedded within structural design provides a lens through which contemporary labor systems can be analyzed. Although the scale and technology differ, the underlying logic remains familiar. Time discipline, surveillance, and economic dependency continue to interact in ways that condition behavior and distribute risk unevenly. The legacy of industrial Britain lies not merely in its machinery but in the enduring recognition that institutional architecture, when aligned with incentive structures, shapes human experience in profound and often predictable ways.

Conclusion: Institutional Design and the Modern Logic of Responsibility

The industrial factory system of nineteenth-century Britain revealed a foundational truth about modern institutions: harm can arise not only from malicious intent but from the ordinary operation of structured environments. What began as a defense of opportunity evolved into a recognition that schedules, spatial arrangements, repetitive tasks, and economic dependency were not neutral mechanisms. They shaped behavior, constrained autonomy, and generated predictable exhaustion. The debate moved beyond the moral character of individual employers to interrogate the architecture of production itself. In doing so, industrial Britain became a crucible for rethinking responsibility in complex societies.

Engels and subsequent reformers played a decisive role in reframing industrial suffering as structural rather than incidental. By documenting patterns of injury, illness, shortened life expectancy, and generational deprivation, they demonstrated that repetition and fatigue were embedded features of factory organization rather than unfortunate deviations from it. Engels’s analysis connected the rhythms of the factory floor to the living conditions of working-class neighborhoods, revealing a coherent system that reproduced vulnerability across domains of life. Legislative responses, including the Factory Acts, signaled an emerging acceptance that foreseeability, not intent alone, grounds accountability. Parliament increasingly recognized that excessive hours and unsafe conditions were not anomalies but predictable consequences of competitive production models. This shift did not abolish exploitation or inequality, nor did it eliminate economic pressures that encouraged overwork. Yet it altered the conceptual terrain. Institutions could be evaluated according to the consequences their design made likely, and responsibility expanded from individual acts to systemic arrangements whose structure shaped behavior.

The enduring relevance of this shift lies in its applicability beyond nineteenth-century industry. Contemporary labor systems, shaped by digital technologies, algorithmic management, and global supply chains, continue to organize time, surveillance, and productivity through institutional design. As in the factory era, the rhetoric of innovation, flexibility, and opportunity often coexists with structural vulnerability and economic precarity. The architecture of contemporary work environments, whether in warehouses, fulfillment centers, or platform-based services, channels behavior through performance metrics and constant monitoring. The modern logic of responsibility depends upon sustained attention to architecture rather than surface intention. When harm is foreseeable within a given configuration of incentives, controls, and dependencies, accountability cannot be confined to personal motive. It must address the structural conditions that render exhaustion, insecurity, or inequality predictable outcomes. The legacy of industrial reform lies precisely in this expanded understanding of causation.

Institutional architecture remains a powerful force in conditioning human behavior. The lesson of industrial Britain is not merely historical; it is conceptual. Systems built to maximize efficiency inevitably shape the lives of those who inhabit them. Recognizing this reality invites a broader understanding of ethical and legal responsibility, one that confronts the structures through which compliance and dependency are produced. In tracing the path from factory discipline to regulatory thought, the history of industrial labor illuminates a continuing challenge: how to align institutional design with human dignity rather than with predictable harm.

Bibliography

- Blayney, Steffan. “Industrial Fatigue and the Productive Body: the Science of Work in Britain, c. 1900–1918.” Social History of Medicine 18:32,2 (2017), 310-328.

- Briggs, Asa. The Age of Improvement, 1783–1867. London: Longman, 1959.

- D’Elia, Nicola. “Friedrich Engels and the Issue of the Revolution in Germany (1883-1895).” International Critical Thought 10:3 (2020), 377-389.

- Engels, Friedrich. The Condition of the Working Class in England. Translated by W. O. Henderson and W. H. Chaloner. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958.

- Horrell, Sara and Jane Humphries. “Children’s Work and Wages in Britain, 1280-1860.” Explorations in Economic History 73 (2019).

- Humphries, Jane. Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Landes, David S. The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

- Parliamentary Papers. Report of the Commissioners for Inquiring into the Employment and Condition of Children in Mines and Manufactories. London, 1843.

- Pollard, Sidney. The Genesis of Modern Management: A Study of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965.

- Srnicek, Nick. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

- Stedman Jones, Gareth. Languages of Class: Studies in English Working Class History 1832–1982. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books, 1963.

- —-. “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism.” Past & Present 38 (1967): 56–97.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2018.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.18.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.