The collapse of the Akkadian Empire was not a sudden catastrophe imposed by an indifferent sky. It was the cumulative result of environmental transformation interacting with political structure.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Climate as Historical Actor

The collapse of the Akkadian Empire in the late third millennium BCE has long occupied a central place in discussions of early imperial fragility. Founded by Sargon of Akkad and consolidated by his successors, the empire represented a new scale of political organization in Mesopotamia, binding together southern irrigated cities and northern rain-fed territories under centralized rule. Administrative standardization, long-distance trade, and military projection marked Akkad as an unprecedented experiment in territorial governance. Its fall around 2200 BCE cannot be treated as a routine dynastic turnover. It coincided with what is now recognized as the 4.2-kiloyear climate event, a prolonged megadrought documented across West Asia, the eastern Mediterranean, and parts of South Asia. The convergence of imperial contraction and environmental destabilization compels historians to reconsider climate not as passive setting, but as an active force shaping material possibility. The Akkadian case stands at the intersection of environmental history and political history, where shifts in rainfall patterns altered the conditions under which power could be maintained.

For much of the twentieth century, explanations for Akkadian decline emphasized familiar political variables: military overextension, internal rebellion, administrative strain, and dynastic instability. These interpretations remain significant, particularly in light of textual traditions that describe unrest and foreign incursions. Yet paleoclimatic research has substantially reframed the problem by introducing independent environmental evidence. Geological cores from the Gulf of Oman, dust deposits in northern Mesopotamia, and isotopic analyses from speleothems and lake sediments collectively indicate a sustained period of aridity beginning around 2200 BCE. Rain-fed agricultural zones in northern Mesopotamia appear to have experienced sharp declines in precipitation, undermining grain production that had become essential to imperial provisioning. Environmental stress was not a brief oscillation within expected variability, but a prolonged and regionally transformative event. Its duration altered settlement patterns, disrupted agricultural rhythms, and strained redistributive networks. The empire’s economic base, especially in its northern territories, was exposed as dependent upon climatic stability that could no longer be assumed.

The presence of drought alone, however, does not automatically produce collapse. Societies have endured climatic fluctuation before and since. What distinguishes the Akkadian case is the apparent mismatch between environmental transformation and institutional response. Contemporary and near-contemporary texts record famine, social disorder, and divine displeasure, yet there is no evidence of structural administrative adaptation proportional to the scale of ecological change. The political system appears to have interpreted crisis as temporary disturbance rather than systemic shift. Climate was experienced, but not fully recognized.

The Akkadian collapse illustrates a broader historical pattern: environmental stress becomes catastrophic when political systems misidentify permanent transformation as cyclical disruption. The 4.2-kiloyear event did not simply weaken Akkad; it exposed the limits of an imperial structure built on assumptions of climatic continuity. Collapse, in this sense, was not caused by drought alone. It emerged from the interaction between ecological change and institutional inertia, where warning signs were visible yet insufficiently assimilated into governance. Climate acted, but political cognition determined the outcome.

The Akkadian Imperial System: Expansion, Extraction, and Ecological Dependence

The Akkadian Empire emerged in the twenty-fourth century BCE as a novel political formation in Mesopotamia. Under Sargon and his successors, authority expanded beyond the traditional city-state model, extending control over southern Sumer, the Diyala region, northern Mesopotamia, and portions of Syria. This expansion was not merely military. It introduced administrative coordination across ecologically diverse zones, integrating irrigated alluvial plains in the south with rain-fed agricultural regions in the north. The empire’s coherence depended upon the regular movement of goods, labor, and tribute across these landscapes. Political authority was inseparable from the management of environmental diversity.

Southern Mesopotamia, defined by the Tigris and Euphrates river systems, relied upon irrigation agriculture. Grain production there was intensive but required constant maintenance of canals, levees, and water distribution systems. Northern Mesopotamia, by contrast, depended more heavily on rainfall agriculture, particularly in the Habur and Upper Khabur regions. In periods of sufficient precipitation, these northern zones produced substantial grain surpluses. Akkadian expansion into these areas likely strengthened imperial provisioning by diversifying its agricultural base. Yet this diversification carried risk. Rain-fed agriculture is inherently more vulnerable to prolonged aridity than irrigated systems drawing from perennial rivers. The empire’s integration of northern dry-farming zones into its economic core bound imperial stability to rainfall patterns beyond administrative control.

Imperial governance required extraction. Tribute, taxation in kind, and forced labor sustained the military apparatus and administrative elite. Textual and archaeological evidence suggests that grain redistribution formed a central component of imperial logistics. Surplus from provincial territories flowed toward urban centers and state projects. This redistributive system functioned effectively only so long as agricultural productivity remained predictable. When harvests failed, the burden of extraction did not disappear; rather, it intensified stress at local levels. Imperial demands could outpace diminished supply, accelerating demographic pressure and social dislocation.

The empire’s territorial breadth further amplified vulnerability. Maintaining garrisons, communication routes, and administrative oversight across vast distances required stable provisioning networks capable of absorbing seasonal variability. Grain shortfalls in northern regions would have reverberated through these systems, affecting not only rural communities but also urban centers dependent upon redistributive flows. A decline in rainfall did not remain localized; it translated into shortages along trade corridors, strained storage systems, and increased reliance on long-distance supply. As rainfall declined, marginal lands likely became untenable, prompting migration toward more stable zones in the south. Such movement placed additional strain on already complex irrigation systems and urban infrastructures, intensifying competition for water and arable land. Ecological stress translated into administrative strain, and administrative strain risked undermining the very coherence that imperial expansion had sought to secure.

Imperial expansion projected permanence. Royal inscriptions emphasized conquest, order, and divine sanction. Kings presented themselves as guarantors of abundance and stability, mediators between divine favor and earthly prosperity. This rhetoric reinforced the assumption that political authority could secure continuity. Yet ideology cannot alter precipitation. The imperial model presupposed environmental reliability even as it expanded into regions where climatic fluctuation posed inherent risk. Confidence in imperial durability may have obscured the fragility embedded in ecological dependence.

The Akkadian imperial system, then, was neither environmentally naive nor uniquely reckless. It represented a rational integration of diverse agricultural zones under centralized administration, combining irrigation engineering in the south with rain-fed production in the north to maximize surplus. Diversification appeared to distribute risk, but in practice it tied the empire to multiple ecological thresholds simultaneously. When prolonged aridity reduced rainfall across northern Mesopotamia, the economic shock was not confined to one province; it rippled through an interconnected network of extraction, redistribution, and military provisioning. Administrative mechanisms designed for expansion proved less adaptable to contraction. The system could compel tribute, but it could not manufacture rainfall. As shortages accumulated and demographic pressures increased, imperial cohesion weakened. Expansion had produced strength through integration, yet that same integration transmitted vulnerability across the entire structure. The empire’s scale magnified both its power and its exposure, leaving it poorly positioned to absorb sustained ecological transformation.

The 4.2-Kiloyear Climate Event: Paleoclimate Evidence and Regional Aridification

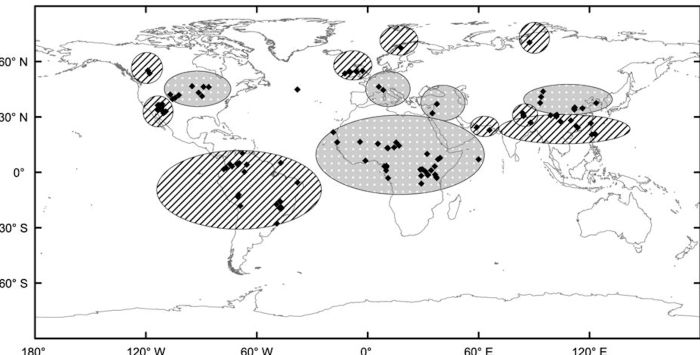

The 4.2-kiloyear climate event, dated to approximately 2200 BCE, represents one of the most extensively studied episodes of abrupt Holocene climate disruption. Identified through multiple paleoclimatic proxies across the Old World, the event is characterized by a sustained period of aridity affecting regions from the eastern Mediterranean to South Asia. In Mesopotamia, its timing corresponds strikingly with the contraction of the Akkadian Empire. While chronological correlation alone cannot establish causation, the convergence of archaeological and climatic evidence invites closer examination. The event was neither a brief oscillation nor a localized drought. It appears to have involved a multi-decade to multi-century reduction in precipitation, altering agricultural viability across rain-fed zones.

One of the earliest and most influential lines of evidence comes from archaeological investigations at Tell Leilan in northeastern Syria. Excavations revealed a distinct abandonment horizon, marked by reduced settlement density and evidence of windblown dust deposits over previously cultivated fields. Harvey Weiss and colleagues argued that this pattern reflected rapid agricultural collapse tied to aridification. The stratigraphic record indicates a sharp decline in occupation around the same period that Akkadian authority weakened. These findings were initially controversial, yet subsequent research has reinforced the interpretation that northern Mesopotamia experienced significant environmental stress.

Marine sediment cores from the Gulf of Oman provide additional support. Analysis of dust flux and isotopic signatures indicates increased aridity in Mesopotamia and adjacent regions during the late third millennium BCE. Elevated levels of eolian dust suggest intensified dry conditions, consistent with weakened monsoon systems and shifts in atmospheric circulation. Speleothem records from caves in the broader Near Eastern region similarly demonstrate changes in precipitation patterns during this period. Together, these independent datasets strengthen the case for a sustained climatic anomaly rather than isolated local drought.

The duration of the event is crucial. Short-term droughts can be mitigated through storage, trade, or temporary migration. A multi-generational decline in rainfall, however, transforms agricultural systems at a structural level. Rain-fed farming in northern Mesopotamia depended upon relatively predictable winter precipitation that replenished soil moisture and sustained cereal cultivation. Even modest reductions in rainfall could sharply decrease yields; prolonged reductions would render marginal lands untenable and progressively shrink the zone of viable cultivation. Archaeological surveys indicate settlement contraction in precisely those areas most dependent on dry farming, particularly along the Habur plains and adjacent steppe margins. Storage systems, however well designed, cannot compensate indefinitely for annual deficits compounded over decades. Nor can short-distance trade networks easily replace lost regional surplus when neighboring zones experience similar stress. This spatial and economic pattern aligns with paleoclimatic reconstructions, suggesting that environmental stress was unevenly distributed but regionally transformative, steadily narrowing the ecological base upon which agrarian life depended.

We must avoid environmental determinism. Climate does not act in isolation. The 4.2-kiloyear event did not uniformly devastate all societies within its reach. Responses varied according to institutional flexibility, economic structure, and geographic context. In southern Mesopotamia, irrigation agriculture buffered some of the immediate impact, although canal systems themselves required maintenance that may have become increasingly difficult amid labor shortages and political instability. The climatic event created conditions of heightened vulnerability, but the degree of disruption depended upon how societies were organized to absorb stress.

The paleoclimatic record reframes the Akkadian collapse not as mysterious decline but as historically situated ecological transformation. The convergence of dust deposits, settlement abandonment, and isotopic data indicates that northern Mesopotamia experienced significant and sustained aridification during the empire’s final century. This environmental shift did not dictate political collapse, yet it restructured the material foundations upon which imperial governance rested. By altering rainfall patterns across key agricultural zones, the 4.2-kiloyear event destabilized surplus production and exposed the fragility embedded in imperial integration. The climate did not overthrow Akkad. It narrowed the range of viable adaptation.

Contemporary Voices: Famine, Disorder, and Imperial Interpretation

While paleoclimatic data reconstruct environmental transformation through geological and atmospheric proxies, Mesopotamian texts provide insight into how crisis was perceived within cultural and political frameworks. The Akkadian period and its aftermath produced literary and administrative materials that reference famine, instability, and social disruption. These sources do not describe climate in modern scientific terms. Instead, they articulate distress through theological and moral language. The interpretive gap between material conditions and textual explanation is itself historically significant. It reveals not ignorance of suffering, but the conceptual limits within which environmental change could be understood.

The most famous text associated with Akkadian decline is the “Curse of Agade.” Composed later, likely during the Ur III period, the work presents the fall of Akkad as divine punishment following royal impiety. The narrative describes agricultural devastation, empty storehouses, and widespread hunger. Fields no longer yield grain; canals cease to produce abundance; cities are abandoned. The text evokes images of cracked earth and silent marketplaces, of once-productive landscapes turned inhospitable. Yet the explanation offered is not drought, nor atmospheric anomaly, nor ecological shift. Instead, the gods withdraw favor in response to sacrilege committed by the king. The crisis is moralized and sacralized, embedded in a cosmic drama of offense and retribution. Environmental collapse becomes a symptom of cosmic disorder, not a natural process requiring structural adaptation. In this framework, restoration depends upon renewed divine favor rather than agricultural reform or administrative restructuring.

Other textual fragments and administrative evidence from the late third millennium BCE indicate economic strain and demographic movement. References to food shortages, disruptions in labor organization, and political unrest suggest that famine was experienced as a lived reality at multiple social levels. Administrative tablets recording rations, labor assignments, and provisioning adjustments point to attempts at crisis management within established bureaucratic norms. However, the language of these materials tends to register scarcity as episodic difficulty rather than systemic transformation. Grain allocations are recalibrated, labor obligations reorganized, and emergency measures enacted, yet these actions operate within an assumption of eventual stabilization. There is little indication that imperial authorities reimagined the agricultural base of the empire or reconsidered the sustainability of northern rain-fed territories. The administrative mindset appears oriented toward managing fluctuation rather than confronting permanent alteration, reflecting confidence that the underlying order could be restored.

This interpretive structure reflects broader Mesopotamian cosmology. Kingship was conceived as a divinely sanctioned office tasked with maintaining order between heaven and earth. Agricultural abundance symbolized divine favor and royal competence. To interpret sustained aridity as environmental shift rather than divine displeasure would have required a conceptual separation between political legitimacy and ecological outcome. Such separation was not easily available within prevailing intellectual traditions. As a result, crisis was framed as rectifiable through ritual restoration, moral correction, or dynastic change rather than structural economic reconfiguration.

The importance of these contemporary voices lies not in their empirical accuracy but in their interpretive posture. The texts demonstrate that famine and disorder were recognized, described, and lamented with striking vividness. They reveal a society acutely aware of suffering and disruption yet committed to explanatory models that located causation in divine will and royal conduct. What they do not show is institutional reconceptualization proportional to environmental evidence now available through paleoclimate research. The Akkadian world did not deny hardship; it absorbed hardship into an inherited moral universe that limited the scope of structural innovation. In doing so, it preserved coherence at the level of meaning even as material conditions deteriorated. The textual record illuminates a crucial dimension of collapse: the translation of ecological stress into culturally intelligible narratives that sustain legitimacy while narrowing adaptive imagination.

Denial and Administrative Inertia: Governance under Environmental Stress

If the paleoclimatic record demonstrates sustained aridity and contemporary texts reveal widespread distress, the question becomes how imperial governance responded in practice. The Akkadian state did not abruptly dissolve at the first sign of agricultural decline. Administrative mechanisms continued to function, military authority remained operative, and royal inscriptions maintained the rhetoric of stability and divine favor. This persistence is not evidence of resilience alone; it may also reflect the structural inertia of complex systems. Large political institutions are designed to preserve continuity. They interpret disruption through frameworks that prioritize restoration rather than transformation. In this context, environmental stress was likely treated as a temporary challenge within an otherwise stable order.

Administrative inertia can operate subtly. Bureaucracies are structured around established procedures, predictable revenue streams, and routinized expectations of surplus. When harvests decline, the immediate response is often to intensify existing mechanisms: adjust rations, reallocate labor, enforce tribute more strictly, or draw upon reserves. Such measures assume that scarcity is cyclical. They are calibrated for fluctuation, not systemic redefinition. In a multi-year drought, however, incremental adjustments may mask the scale of structural change. The very competence of administrative systems in managing short-term crises can delay recognition that conditions have crossed a threshold beyond which prior norms are no longer viable.

The Akkadian Empire’s integration of northern rain-fed regions into its provisioning network compounded this challenge. Continued demands for tribute and grain may have accelerated rural depletion in areas already experiencing reduced rainfall. As yields declined, extraction became more burdensome, potentially driving migration and abandonment of marginal settlements. Communities facing repeated harvest failures would have struggled to meet imperial quotas, forcing local authorities to choose between compliance and survival. Imperial authority, dependent upon visible displays of order and control, had limited incentive to acknowledge contraction openly. To concede that climatic conditions had fundamentally shifted would be to admit limits to royal capacity and divine favor. Political legitimacy may have reinforced interpretive conservatism, sustaining confidence in restoration even as ecological realities diverged from expectation. In this dynamic, enforcement mechanisms that once stabilized the empire risked intensifying the very fragility they were meant to prevent.

Evidence of continued monumental activity and royal assertion during the empire’s late phases underscores this dynamic. Rulers such as Naram-Sin presented themselves as divinely favored and militarily triumphant. Such representations were not mere propaganda in the modern sense; they were embedded within a worldview that linked kingship to cosmic order. Yet the maintenance of imperial image amid deteriorating agricultural conditions suggests a disjunction between ideological continuity and material instability. Governance proceeded as though the system remained fundamentally sound, even if temporarily strained. Administrative forms persisted longer than the environmental conditions that had sustained them.

Denial need not imply conscious refusal to see reality. It can emerge from structural commitment to continuity and from the psychological investment of elites in the permanence of their institutions. Political systems are oriented toward preserving themselves; they are rarely designed to reconceptualize their foundational assumptions rapidly, particularly when those assumptions are intertwined with sacred legitimacy. The Akkadian state appears to have managed scarcity through established procedures until those procedures ceased to function effectively. By the time adaptation required territorial contraction, economic reorientation, or fundamental administrative redesign, the ecological shift may have already rendered recovery improbable. Administrative inertia transformed environmental stress into political collapse, not because warning signs were absent, but because institutional frameworks were ill-equipped to interpret them as permanent transformation. In this sense, governance under drought did not fail immediately; it failed gradually, as the persistence of normal procedure masked the erosion of structural viability.

Collapse as Abandonment: Demographic Shift and Political Fragmentation

The end of the Akkadian Empire did not occur as a single dramatic event but unfolded through a process of contraction and abandonment. Archaeological surveys across northern Mesopotamia indicate significant declines in settlement density in the late third millennium BCE. Sites that had flourished under imperial integration show reduced occupation layers or complete desertion. This pattern is especially visible in regions dependent upon rain-fed agriculture, where prolonged aridity would have rendered cultivation increasingly untenable. The archaeological record suggests that collapse was not solely administrative or dynastic. It was spatial.

Demographic movement appears to have accompanied this contraction. As northern agricultural productivity declined, populations likely migrated toward more stable zones in southern Mesopotamia, where irrigation agriculture offered relative buffering against rainfall variability. Such migration would not have occurred instantaneously but gradually, as repeated harvest failures eroded household resilience and local storage capacity. Families facing sustained deficits would have sought proximity to canal systems, urban redistribution centers, or temple-based provisioning networks. This movement altered labor markets, intensified demands on irrigation infrastructure, and may have contributed to competition over access to arable land. Irrigation systems, already complex and maintenance-intensive, required coordinated labor for dredging, levee repair, and water management. An influx of migrants could increase available labor, but it could also strain administrative capacity and social cohesion. Rather than restoring imperial equilibrium, demographic concentration in the south may have accelerated social strain, amplified urban crowding, and contributed to the fragmentation of political authority as provincial regions slipped beyond effective control.

Political fragmentation followed ecological and demographic shift. After the decline of Akkadian centralized control, regional polities emerged, including the rise of the Gutian period and later the Ur III state. These successor regimes did not replicate Akkadian territorial breadth immediately. Instead, they reflect a reorganization of power under altered material conditions. The imperial model that had integrated diverse ecological zones gave way to more regionally focused structures. Fragmentation, in this sense, was not mere failure but adaptation to a landscape whose agricultural capacity had changed.

Abandonment also reshaped economic networks. Long-distance trade routes connecting northern Mesopotamia to Anatolia and Syria appear to have diminished in intensity during this period, as evidenced by shifts in material culture and reduced distribution of certain imported goods. Reduced agricultural surplus would have limited the capacity to sustain exchange at earlier levels, particularly when caravan networks depended upon stable provisioning nodes. Urban contraction, combined with shifting population patterns, altered the geography of economic interaction. Administrative centers that once coordinated extraction and redistribution across wide territories lost their integrative function. Economic life became more localized, oriented toward regional circuits capable of operating within diminished surplus conditions. This transformation underscores that collapse is not simple disappearance but structural reconfiguration, in which scale contracts and networks recalibrate around new ecological constraints.

The Akkadian collapse was less an implosion than a withdrawal from ecological zones that could no longer sustain imperial expectations. The abandonment of northern territories signaled recognition, whether gradual or reluctant, that previous patterns of integration were no longer viable. Political authority fragmented because the material basis for large-scale coordination had eroded. The empire did not disintegrate into nothingness; it contracted into forms more compatible with altered environmental realities. Collapse was not annihilation. It was the relinquishing of scale.

Structural Lesson: Environmental Signals and Political Cognition

The Akkadian case invites a broader analytical question: how do political systems interpret environmental signals? The 4.2-kiloyear event did not occur invisibly. Harvest failures, dust accumulation, migration, and food shortages would have been materially apparent to administrators and rural communities alike. Fields would have yielded less grain; storage facilities would have emptied more quickly; pastoral routes would have shifted in response to declining pasture. Such indicators accumulate gradually, rarely announcing themselves as epochal change. Yet visibility does not guarantee recognition at the level of structural transformation. Environmental signals can be experienced as disruption without being conceptualized as permanence. The distinction is critical. Political systems calibrated for cyclical variability may interpret sustained change through the lens of temporary deviation, absorbing early warning signs into familiar categories of fluctuation. In doing so, they postpone redefinition of strategy until the material basis of stability has already begun to erode beyond easy repair.

This gap between signal and cognition reflects institutional design. Complex societies develop administrative routines, ideological narratives, and economic dependencies that presuppose continuity. Such systems are efficient within stable parameters but resistant to rapid redefinition. When environmental conditions shift beyond expected oscillation, the initial response is often intensification of established procedures rather than reconsideration of foundational assumptions. In the Akkadian Empire, tribute systems, labor organization, and territorial integration persisted as if underlying ecological conditions would normalize. The machinery of governance remained intact longer than the environmental patterns that had sustained it.

Political cognition is further shaped by legitimacy structures. In Mesopotamia, kingship was embedded in theological frameworks linking divine favor to material abundance. Acknowledging that climatic deterioration might represent structural environmental change rather than divine displeasure required conceptual tools that were not readily available within prevailing cosmologies. Interpretive authority rested with religious and royal institutions whose explanatory models reinforced continuity between moral order and ecological outcome. Modern states operate within different epistemologies grounded in scientific data and bureaucratic expertise, yet they are not immune to similar constraints. Economic growth paradigms, infrastructural investments, and political commitments to stability can create incentives to frame environmental stress as manageable anomaly rather than systemic rupture. The problem is rarely absence of evidence. It is the difficulty of translating accumulating data into institutional redesign without undermining legitimacy or entrenched expectations. Recognition carries political cost, and that cost can delay acknowledgment of thresholds already in motion.

The structural lesson is not that ancient societies failed uniquely, but that complex systems often struggle to distinguish fluctuation from transformation. Environmental stress becomes catastrophic when warning signals are assimilated into narratives of temporary disruption. The Akkadian collapse demonstrates that adaptation delayed can become adaptation impossible. By the time abandonment replaced reform, ecological conditions had already narrowed the range of viable response. Climate acted over decades. Political cognition lagged behind. The result was not sudden annihilation but the gradual relinquishing of imperial scale under conditions that had ceased to sustain it.

Past Is Present: Climate Warning, Political Denial, and Modern Structural Risk

The Akkadian collapse does not provide a script for modern catastrophe, nor should ancient precedent be forced into contemporary polemic. Yet it does illuminate a structural pattern that recurs across time: environmental warning signs can be empirically visible while politically assimilated as manageable deviation. In the twenty-first century, climatic data are not inferred from dust deposits alone. They are measured in atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, global temperature averages, glacial retreat, sea-level rise, and intensifying extreme weather events. The informational environment is saturated with evidence. The question is not whether signals exist, but how institutions interpret them.

Modern political systems possess scientific agencies, climate models, and intergovernmental research bodies capable of translating environmental data into policy recommendations. Reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change describe anthropogenic warming with increasing precision and confidence. Yet institutional response remains uneven. Economic structures dependent upon fossil fuels, infrastructural commitments to carbon-intensive growth, and partisan polarization complicate policy adaptation. As in Akkad, administrative machinery often proceeds under assumptions of continuity, seeking incremental adjustment rather than structural redesign.

Under the current administration of President Donald Trump, federal climate policy has undergone significant retrenchment. References to climate change have been reduced or removed from certain government websites, funding for climate-related research has faced proposed reductions, and the Environmental Protection Agency has shifted its public framing away from treating climate change as a central regulatory priority. Public communications that once emphasized anthropogenic causation have been recalibrated, and advisory structures have been reorganized in ways that elevate economic considerations over mitigation targets. Such measures do not alter atmospheric chemistry, nor do they negate decades of accumulated climate science. They do, however, reshape the institutional environment in which policy is formulated. When executive authority narrows the scope of recognized crisis, it signals to agencies, industries, and the public that climate risk occupies a diminished position within federal priorities. The effect is cumulative. Administrative emphasis shapes funding streams, research agendas, and regulatory enforcement, thereby influencing the pace and scale of adaptive transition.

This dynamic does not require explicit denial of observable phenomena. It can operate through procedural recalibration: redefining agency priorities, revising public communications, or restructuring advisory frameworks. Political leaders may frame climate variability as natural fluctuation, emphasize economic growth over mitigation, or defer structural transition in favor of technological optimism. These approaches can coexist with scientific awareness at lower bureaucratic levels, producing a fragmented institutional cognition in which data circulate without decisive structural translation. The gap between evidence and redesign widens.

The structural risk lies not in disagreement alone, but in temporal compression. Climate systems operate over decades and centuries, yet political cycles are measured in years, sometimes in months. Incremental delay accumulates, and the compounding nature of greenhouse gas emissions means that postponement today shapes climatic baselines tomorrow. Infrastructure decisions concerning energy production, transportation networks, and urban development lock in emissions trajectories that persist for generations. As the Akkadian example suggests, adaptation calibrated for short-term fluctuation can fail when environmental change crosses thresholds that render prior models obsolete. Modern societies possess scientific foresight unavailable in antiquity, but foresight does not automatically produce coordination or political will. Recognition without redesign risks replicating the inertia that transformed drought into collapse, particularly when mitigation becomes more expensive and technologically demanding with each passing year of inaction.

The lesson is not that contemporary states are destined for Akkadian outcomes. Modern economies are more diversified, technologically adaptive, and globally interconnected, with capacities for rapid innovation and large-scale mobilization. Yet interconnectedness can amplify vulnerability as well as resilience, transmitting supply disruptions, migration pressures, and economic shocks across borders with unprecedented speed. The enduring parallel lies in political cognition and institutional response. Environmental signals may be measured with extraordinary precision, yet acknowledgment can remain contested, strategically reframed, or administratively diluted. The past demonstrates that collapse need not arise from ignorance of warning signs. It can emerge when political systems persist in treating structural transformation as temporary disturbance, prioritizing continuity of model over recalibration of structure. Climate acts gradually but relentlessly. The decisive variable is whether governance adapts before ecological thresholds narrow the field of viable response and convert manageable transition into irreversible constraint.

Conclusion: When Mitigation Becomes Impossible

The collapse of the Akkadian Empire was not a sudden catastrophe imposed by an indifferent sky. It was the cumulative result of environmental transformation interacting with political structure. The 4.2-kiloyear megadrought altered rainfall patterns across northern Mesopotamia, reducing agricultural productivity and destabilizing surplus networks. Yet drought alone did not dissolve imperial authority. Collapse emerged from the misalignment between ecological change and institutional adaptation. Governance continued, tribute systems operated, and royal ideology persisted even as the material foundations of imperial integration eroded. Mitigation became increasingly difficult not because warning signs were absent, but because they were interpreted within frameworks calibrated for fluctuation rather than transformation.

The Akkadian case underscores a critical threshold dynamic. Short-term scarcity can be absorbed; long-term aridification restructures viability. Administrative responses designed for temporary deficit proved inadequate when environmental change extended beyond expected cycles. By the time contraction became unavoidable, the empire’s northern territories were no longer capable of sustaining the scale of integration previously achieved. Reform, in that context, was no longer a matter of adjustment. It required relinquishment of imperial breadth. Adaptation delayed narrowed the range of possible adaptation later. What might have been managed incrementally became irreversible structurally.

This pattern carries analytical significance beyond antiquity. Complex systems are resilient within defined parameters, yet they are vulnerable when foundational assumptions about environmental stability are disrupted. Recognition of risk does not automatically produce redesign, particularly when legitimacy, economic structure, and political continuity are intertwined. The decisive question is temporal: at what point does mitigation shift from difficult to impossible? The Akkadian experience suggests that the window between signal and threshold can close gradually and almost imperceptibly. When that window closes, abandonment replaces reform.

Climate is neither villain nor destiny. It is a force that narrows or expands the range of viable political organization. The fall of Akkad demonstrates that collapse need not arise from ignorance or chaos. It can arise from persistence, from the continuation of normal procedure amid abnormal conditions. Environmental transformation tests not only material capacity but institutional imagination. When governance fails to reconceive its foundations in time, mitigation yields to contraction. The lesson is stark: ecological thresholds are crossed in silence, and once crossed, they redefine what recovery can mean.

Bibliography

- Adams, Robert McC. Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- —-. Land Behind Baghdad: A History of Settlement on the Diyala Plains. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

- Butzer, Karl W. “Collapse, Environment, and Society.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:10 (2012), 3632–3639.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. The Curse of Agade. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

- Cullen, Heidi M., et al. “Climate Change and the Collapse of the Akkadian Empire.” Geology 28:4 (2000), 379–382.

- Foster, Benjamin R. The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia. London: Routledge, 2016.

- —-. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. Bethesda: CDL Press, 2005.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report. Geneva: IPCC, 2021.

- Liverani, Mario. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. London: Routledge, 2013.

- —-. International Relations in the Ancient Near East, 1600–1100 BC. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

- —-. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Staubwasser, Michael, and Harvey Weiss. “Holocene Climate and Cultural Evolution in Late Prehistoric–Early Historic West Asia.” Quaternary Research 66 (2006): 372–387.

- Tainter, Joseph A. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Ur, Jason. “Cycles of Civilization in Northern Mesopotamia.” Journal of Archaeological Research 18 (2010), 387–431.

- Weiss, Harvey, et al. “The Genesis and Collapse of Third Millennium North Mesopotamian Civilization.” Science 261:5124 (1993), 995–1004.

- —-, ed. Megadrought and Collapse: From Early Agriculture to Angkor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.19.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.