The Aral Sea stands as one of the clearest modern demonstrations that ecological collapse can unfold within a system saturated with information.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Collapse in an Age of Data

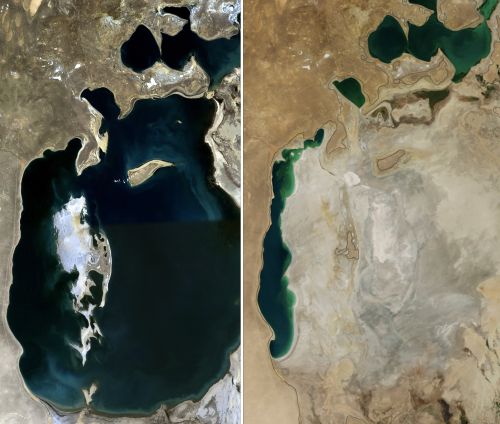

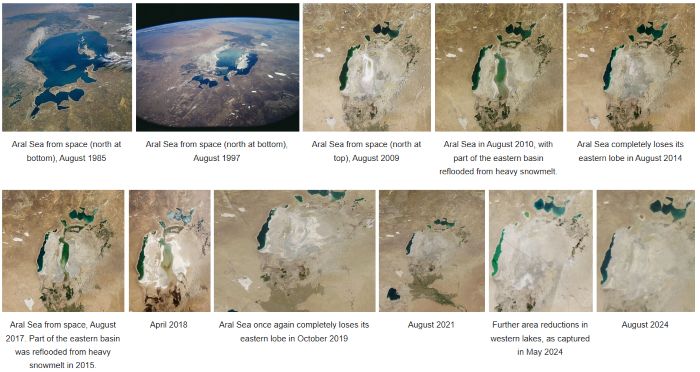

The desiccation of the Aral Sea stands among the most striking environmental transformations of the twentieth century. Once the fourth-largest inland water body in the world, covering more than 60,000 square kilometers at its mid-century extent, the sea sustained commercial fisheries, buffered regional temperature extremes, and shaped the economic and cultural life of communities across Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Ports such as Aralsk and Muynak thrived as maritime centers in what is today an arid landscape. Within a few decades, however, the shoreline retreated dramatically, leaving rusting fishing vessels stranded on exposed seabed and transforming coastal settlements into inland towns. Salinity levels rose, biodiversity declined, and the sea fragmented into disconnected basins separated by expanding salt flats. By the late Soviet period, cartography itself struggled to keep pace with hydrological change. The scale and speed of this transformation have often invited moral judgment, yet the more analytically important feature of the Aral Sea disaster lies in its historical context. This was not an ancient society without measurement, writing, or engineering capacity. It was a modern, industrial state rich in hydrological data, engineering expertise, centralized statistical systems, and the institutional infrastructure to observe ecological change in real time.

Late Soviet governance prided itself on technocratic rationality. Five-Year Plans, production quotas, and centralized statistical systems reflected a belief that complex social and economic systems could be measured, directed, and optimized. The diversion of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to support large-scale irrigation, particularly for cotton cultivation, emerged from this confidence in hydraulic engineering and planning. River flows were monitored. Salinity levels were recorded. Agricultural outputs were quantified. The Soviet Union possessed scientists capable of modeling ecological consequences, and many did. The collapse of the Aral Sea unfolded not in the absence of data, but amid its proliferation.

Early scientific assessments warned that sustained diversion of inflowing rivers would reduce water levels and increase salinity. Hydrologists documented declining inflows by the 1960s and 1970s, projecting fisheries collapse and ecological disruption if irrigation withdrawals continued unchecked. These warnings circulated within academic and bureaucratic institutions. Yet policy priorities remained anchored to production targets and ideological commitments to transforming Central Asia into a cotton-producing powerhouse. Environmental consequences were framed as manageable trade-offs or deferred concerns. The persistence of river diversion despite mounting evidence of harm reveals a critical tension between scientific clarity and political will.

The Aral Sea disaster represents collapse in an age of data. It challenges the assumption that knowledge alone prevents ecological catastrophe. In the Soviet case, environmental degradation occurred within a system capable of measuring it. Denial did not take the form of ignorance but of institutional prioritization. Production targets, ideological narratives of modernization, and bureaucratic incentives outweighed ecological restraint. By the time policy shifts acknowledged the severity of the crisis, the ecosystem had crossed thresholds beyond meaningful restoration. The Aral Sea illustrates how modern states can move toward irreversibility not because they lack information, but because their structures reward continuity even when evidence points toward collapse.

Ecological Foundations: The Aral Sea before Diversion

Before large-scale river diversion began in the mid-twentieth century, the Aral Sea functioned as a relatively stable terminal lake within an arid continental environment. Fed primarily by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, the sea’s water balance depended on the equilibrium between inflow and evaporation, a delicate hydrological relationship shaped by seasonal snowmelt in distant mountain ranges. Although natural fluctuations occurred over centuries, geological and historical evidence suggests that the basin maintained a dynamic stability capable of sustaining both ecological diversity and human settlement. Salinity levels were moderate enough to support a productive fishery, and the sea moderated regional climate by buffering temperature extremes and contributing moisture to surrounding areas. In an otherwise dry landscape, the Aral Sea acted as a stabilizing environmental presence, integrating river systems, wetlands, and coastal settlements into a coherent ecological zone.

The rivers that fed the Aral Sea carried not only water but sediment and nutrients from distant mountain ranges. Originating in the Pamir and Tien Shan mountains, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya flowed across Central Asia, sustaining irrigation agriculture long before Soviet rule. Seasonal floods replenished soils and maintained wetlands along their courses. By the time the rivers reached the Aral basin, they had supported multiple ecological zones, linking upland snowmelt to lowland delta systems. The deltas themselves formed rich habitats for fish, birds, and plant species, reinforcing the productivity of the sea.

Human communities along the Aral coast developed livelihoods closely tied to this hydrological system. Commercial fishing expanded during the late imperial and early Soviet periods, with annual catches reaching tens of thousands of tons by the mid-twentieth century. Fish processing plants, transport networks, and port infrastructure connected coastal settlements to broader markets within the Soviet Union. Entire towns oriented their economic rhythms around seasonal harvests from the sea, and generational knowledge accumulated in fishing techniques, navigation, and processing practices. The sea was not an isolated body of water but an integrated component of regional economic life. Maritime culture and industrial activity coexisted with subsistence practices in surrounding rural areas, creating a diversified economy anchored in hydrological stability.

Salinity levels before large-scale diversion averaged roughly one-third that of ocean water, supporting species such as sturgeon, carp, and bream. The ecological web extended beyond fish stocks. Wetlands at the river deltas provided nesting grounds for migratory birds and acted as natural filters for riverine sediments. The sea’s presence also influenced local microclimates, moderating winters and summers in adjacent areas. These environmental services were not abstract benefits but lived conditions shaping agricultural cycles and community stability.

The pre-diversion Aral Sea represented a system of interdependent balances. Hydrological inflow, evaporation, salinity, fisheries, and human settlement operated within a framework that, while vulnerable to fluctuation, remained resilient over long periods. This equilibrium supported both ecological productivity and social organization, linking distant mountain hydrology to coastal industry and everyday subsistence. The sea’s relative stability fostered infrastructure investment, demographic growth, and institutional confidence in its permanence. This equilibrium did not imply ecological permanence, but it provided a baseline against which later transformation can be measured. Understanding the sea’s former stability clarifies the scale of change that followed. The environmental disaster of the late Soviet era did not occur in a vacuum; it disrupted a functioning and historically sustained ecological order whose complexity and resilience had long been taken for granted.

Hydraulic Ambition: Cotton, Central Planning, and River Diversion

The transformation of the Aral Sea basin began not as an environmental project but as an agricultural and ideological one. In the postwar decades, Soviet planners intensified efforts to expand cotton production across Central Asia. Cotton was designated a strategic commodity, often referred to as “white gold,” essential to textile manufacturing and to the broader economic objectives of the state. Central planners viewed the arid lands of Uzbekistan and surrounding republics not as ecological systems to be preserved, but as spaces to be rationally reorganized for maximum output. Rivers that had sustained diverse ecosystems were reconceived as inputs to be redirected toward irrigated monoculture.

The expansion of irrigation infrastructure accelerated during the 1960s. Massive canal systems, including the Karakum Canal, diverted substantial volumes of water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya before they could reach the Aral Sea. These engineering projects reflected a confidence in hydraulic transformation that had characterized Soviet development policy for decades, drawing on earlier experiences with dam building and river regulation across the Union. Water, in this framework, was a controllable resource subject to calculation, redirection, and optimization according to centrally determined goals. Centralized planning mechanisms tracked irrigation acreage, cotton yields, and projected economic gains through detailed statistical reporting. Ministries coordinated with regional authorities to ensure that quotas were met, while infrastructure investment continued to prioritize canal expansion and pumping capacity. The ecological implications of reduced downstream flow were acknowledged in technical reports, but they remained secondary to production targets embedded in Five-Year Plans and ideological commitments to agricultural self-sufficiency.

Cotton monoculture became the organizing principle of regional development. Vast tracts of land were converted to irrigated fields, and quotas incentivized continual expansion. Local officials were evaluated on their ability to meet or exceed output expectations, reinforcing a cycle of increased water withdrawal. The political economy of cotton tied regional elites to central authorities through patronage networks and statistical reporting systems. In this environment, river diversion was not a temporary adjustment but a structural commitment. The more irrigation infrastructure expanded, the more institutional momentum accumulated behind continued water extraction.

Technocratic optimism further reinforced this trajectory. Soviet engineers and planners possessed considerable expertise in dam construction, canal design, and water management. Large-scale hydraulic projects were celebrated as symbols of modernity, scientific progress, and state capacity. The redirection of rivers was framed as an expression of human mastery over nature, consistent with ideological narratives of socialist transformation and modernization of “backward” regions. In official discourse, irrigation represented liberation from climatic constraint and proof of centralized planning’s superiority over market-driven agriculture. In such a climate, environmental constraints were often treated as technical problems to be solved through further engineering rather than as structural limits requiring restraint. Declining inflows to the Aral Sea were interpreted as variables to be managed, potentially offset by additional canals, reservoirs, or efficiency improvements. The underlying assumption remained that sufficient planning and technological intervention could reconcile ambitious agricultural targets with ecological stability.

By the early 1970s, measurable reductions in river discharge were evident. Hydrological data recorded falling sea levels and increasing salinity, trends documented by scientific institutes within the Soviet system. Fisheries began to experience strain as ecological conditions shifted, and coastal communities observed tangible changes in shoreline distance and fish stocks. Yet irrigation withdrawals continued to rise. The institutional architecture of central planning rewarded persistence in cotton production, while responsibility for ecological consequences was diffused across ministries, planning committees, and republic-level administrations. Each administrative unit pursued its own production targets within a broader framework that prioritized output above all else. No single authority bore direct accountability for the sea’s decline, and the cumulative effect of countless incremental diversions, each justified within production logic, produced a systemic outcome that no single decision alone had mandated. The absence of concentrated responsibility facilitated continued extraction even as warning signs multiplied.

Hydraulic ambition reshaped the Aral basin through a convergence of ideology, economic incentive, and administrative structure. River diversion was not an unintended accident but the predictable outcome of a system that privileged output over ecological equilibrium. As canals lengthened and fields expanded, the Aral Sea’s inflow diminished beyond sustainable limits. The transformation unfolded within a framework that celebrated quantitative achievement and technical control, even as the ecological cost became increasingly visible. By embedding river diversion within the core objectives of state planning, Soviet authorities set in motion a trajectory that would prove difficult to reverse.

Scientific Warning and Institutional Refusal

By the late 1960s, Soviet hydrologists and environmental scientists had begun documenting measurable changes in the Aral Sea’s water balance. River discharge records showed sustained declines in inflow as irrigation withdrawals expanded upstream. Early hydrological models projected that continued diversion would lower sea levels significantly and raise salinity beyond thresholds compatible with established fisheries. These were not marginal voices operating outside state structures. The data were generated by state-funded research institutes and circulated within planning ministries responsible for water management and agricultural policy. Technical memoranda, conference proceedings, and internal assessments mapped the trajectory of decline with increasing precision. Scientific awareness preceded visible ecological catastrophe, and the potential path toward severe contraction was understood in quantitative terms well before the sea fragmented into separate basins.

Warnings extended beyond water levels. Researchers projected that rising salinity would devastate fisheries, undermining one of the region’s key economic sectors. Ecologists emphasized the vulnerability of delta wetlands and bird habitats. Climatologists cautioned that the shrinking sea could alter regional weather patterns, intensifying temperature extremes and reducing humidity. By the early 1970s, evidence indicated that fish stocks were declining and shoreline retreat was accelerating. Scientific clarity, in this case, did not emerge only after irreversible damage. It accompanied the process in real time, generating an expanding body of empirical documentation.

Despite this growing body of evidence, institutional responses remained limited. Policy discussions often framed environmental degradation as an acceptable cost of agricultural modernization. Cotton production targets continued to dominate planning priorities, and irrigation expansion proceeded. Responsibility for the Aral Sea was dispersed among multiple ministries, including those overseeing water management, agriculture, and fisheries. This fragmentation complicated coordinated action. Even when individual scientists advocated restraint or partial reallocation of river flows, their recommendations competed with entrenched economic objectives and bureaucratic inertia.

Ideological commitment reinforced institutional refusal. Soviet development policy emphasized the transformative power of centralized planning and engineering, portraying large-scale environmental modification as evidence of progress and scientific mastery. Hydraulic projects were symbols of modernity, celebrated in official rhetoric and public discourse. Acknowledging that river diversion had produced systemic ecological harm risked undermining the legitimacy of planning institutions and the narrative of socialist achievement in Central Asia. Environmental costs were minimized rhetorically, reframed as temporary dislocations, or deferred to future technical remedies. The assumption persisted that improved irrigation efficiency, additional reservoirs, or further scientific study could mitigate emerging problems without requiring a fundamental reduction in cotton production. In this ideological climate, to reverse diversion policy would have signaled not only economic recalibration but political concession.

Scientific warning without political realignment proved insufficient to alter the trajectory of decline. Data accumulated, reports circulated, and statistical indicators tracked the sea’s retreat, yet institutional incentives remained aligned with production continuity. The persistence of diversion despite mounting evidence illustrates denial not as ignorance but as prioritization within a rigid administrative framework. The Soviet system possessed the technical capacity to observe environmental deterioration in detail, but it lacked the structural flexibility and political willingness to subordinate ideological and economic goals to ecological sustainability. Institutional refusal operated not solely through suppression of information, but through the systematic elevation of output metrics over environmental limits. As long as cotton quotas defined success, ecological thresholds could be crossed while the machinery of planning continued to function as designed.

The Tipping Point: Salinization, Fisheries Collapse, and Ecological Death

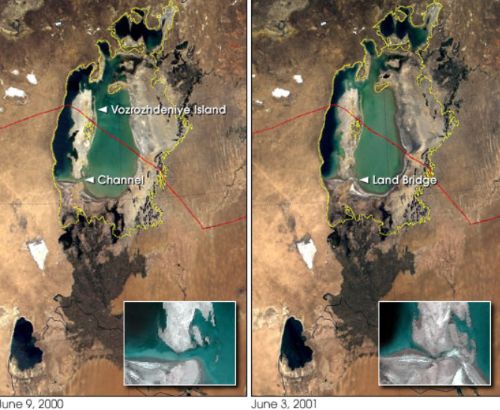

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the cumulative effects of sustained river diversion moved beyond incremental stress into systemic transformation. For nearly two decades, declining inflows had produced measurable but gradual reductions in water level. Eventually, the hydrological balance shifted decisively. The Aral Sea’s water level fell steadily as inflows from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya dropped far below evaporation rates characteristic of the region’s arid climate. Shorelines retreated dramatically, in some areas by dozens of kilometers, leaving former ports stranded inland and transforming maritime towns into desert settlements. Satellite imagery and ground surveys documented the accelerating contraction, revealing exposed seabed where open water had existed only years before. What had once been a contiguous body of water began fragmenting into smaller basins separated by expanding salt flats. The tipping point was not a single event but a measurable shift in hydrological equilibrium from fluctuation to irreversible contraction, marking the transition from stressed system to fundamentally altered ecosystem.

Salinity levels rose in direct proportion to declining water volume. As freshwater inflow diminished, salts accumulated in shrinking basins. By the 1980s, salinity had increased beyond the tolerance range of most native fish species. Commercial fisheries collapsed, eliminating a central pillar of regional economic life. Processing plants closed, fleets were abandoned, and coastal communities experienced rapid economic decline. The ecological web that had sustained fisheries, including delta wetlands and breeding grounds, deteriorated simultaneously. The sea ceased to function as a viable aquatic ecosystem in its historical form.

The ecological death of the Aral Sea extended beyond the loss of fish stocks. Exposed seabed, once submerged under brackish water, transformed into vast salt flats. Winds carried salt and residual agricultural chemicals across surrounding regions, creating toxic dust storms that affected human health and crop productivity. Increased respiratory illness, soil contamination, and declining agricultural yields compounded the social costs of environmental collapse. The sea’s retreat altered local climate patterns, intensifying summer heat and winter cold. A feedback loop emerged in which ecological degradation reinforced socioeconomic vulnerability.

Fragmentation of the sea into separate northern and southern basins marked the consolidation of irreversible change. As water levels fell, the sea divided into what became known as the North Aral Sea and the much larger South Aral Sea, each following a distinct trajectory. The southern basin, receiving minimal inflow due to upstream diversion, shrank drastically and in some years nearly disappeared, leaving behind hyper-saline pools incapable of sustaining historical biodiversity. The northern basin, though diminished, retained partial hydrological viability because of comparatively greater inflow from the Syr Darya. This bifurcation underscored the uneven distribution of remaining resources and highlighted the structural consequences of sustained diversion policy. By this stage, the system had crossed a threshold beyond which restoration of the original sea was no longer plausible without massive and politically unrealistic reallocation of river flows across Central Asia. The tipping point was visible on satellite imagery and measurable in salinity data. Ecological death was no longer predictive; it was observable and ongoing.

The collapse of fisheries symbolized the broader structural shift. What had been a renewable resource embedded in hydrological equilibrium became untenable within a highly saline and reduced basin. Attempts to introduce salt-tolerant species yielded limited and temporary results. Economic substitution did not compensate for the loss of maritime livelihoods. The transformation from a productive inland sea to a saline remnant altered demographic patterns as communities migrated in search of employment. Ecological thresholds translated directly into social contraction.

The tipping point of the Aral Sea represents the culmination of sustained institutional prioritization of production over equilibrium. Once salinity exceeded biological tolerance and hydrological fragmentation advanced, mitigation options narrowed to damage control rather than restoration. Efforts in subsequent decades focused on partial stabilization of the northern basin, while the southern expanse continued to deteriorate. The system no longer oscillated within recoverable limits; it had shifted into a new ecological state defined by reduced volume, elevated salinity, and degraded function. In crossing this threshold, the Aral Sea exemplified ecological irreversibility in a modern, data-rich context. The sea’s decline was not speculative or delayed; it was measured, mapped, and endured, demonstrating that even in an age of scientific clarity, environmental systems can be driven beyond recovery when institutional priorities remain misaligned with ecological limits.

Late Recognition: From Mitigation to Damage Control

By the mid-1980s, the scale of the Aral Sea’s decline had become impossible to ignore. Satellite imagery, falling fisheries statistics, and the visible retreat of shorelines transformed what had once been internal scientific concern into public knowledge. During the era of glasnost, greater openness allowed journalists and environmental advocates to document the crisis more openly. Official discourse shifted from quiet minimization to acknowledgment of severe ecological damage. Yet recognition came at a stage when the structural drivers of collapse had already operated for decades. The hydrological system had crossed thresholds that could not be reversed through incremental policy adjustment.

Policy discussions began to explore mitigation strategies, including improved irrigation efficiency and partial redirection of river flow. Technical experts proposed lining canals to reduce seepage, modernizing irrigation methods to decrease water loss, and recalibrating allocation schemes among upstream republics. Some proposals envisioned large-scale engineering solutions, such as inter-basin water transfers from Siberian rivers, intended to compensate for lost inflow and restore the sea’s volume. However, these plans faced economic, political, and logistical constraints of immense scale. The cost of massive infrastructure projects collided with the Soviet Union’s mounting fiscal pressures in the 1980s. Moreover, meaningful restoration would have required significant reductions in cotton production, challenging entrenched regional economic systems and bureaucratic interests. Even where technical capacity existed, the scale of required water reallocation conflicted directly with established agricultural production structures and long-standing policy commitments. Mitigation, in theory expansive, became in practice constrained by institutional realities.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, newly independent Central Asian states inherited both the environmental crisis and the institutional structures that had produced it. International organizations, including the World Bank, supported targeted interventions, particularly in the northern basin. Construction of the Kok-Aral Dam in Kazakhstan in the early twenty-first century successfully stabilized and partially restored the North Aral Sea, reducing salinity and reviving limited fisheries. This achievement demonstrated that localized recovery was possible under specific conditions. Yet the southern basin, primarily in Uzbekistan, continued to deteriorate, illustrating the limits of partial mitigation in a fragmented system.

The distinction between restoration and damage control became increasingly clear. Full recovery of the Aral Sea to its mid-twentieth-century extent would have required dramatic reductions in irrigation withdrawals across multiple sovereign states, a political coordination problem far more complex than any single engineering solution. Instead, policy shifted toward managing consequences: addressing public health crises from toxic dust, adapting agricultural practices to saline soils, and stabilizing remaining water bodies where feasible. The language of sustainability gave way to the pragmatics of containment. Ecological ambition narrowed in proportion to diminished possibility.

Late recognition altered rhetoric more than hydrological reality. Scientific clarity had long preceded public acknowledgment, but institutional change arrived only after irreversibility had set in. The shift from denial to admission did not automatically produce restoration, because the ecological and economic systems had already reoriented around a diminished sea. Mitigation efforts mitigated some local effects, yet they did not reverse the core transformation of the basin. Instead, policy became oriented toward limiting further harm, reducing exposure to toxic dust, and preserving fragments of the original ecosystem where feasible. The Aral Sea case demonstrates how policy response can shift from prevention to management once tipping points are crossed. By the time environmental crisis becomes politically undeniable, options may already be structurally constrained. What remains is not restoration of a lost equilibrium but adaptation to a new and diminished ecological state that reflects decades of accumulated decision-making.

Denial in a Data-Rich System

The Aral Sea disaster challenges a common assumption in environmental governance: that the accumulation of scientific data naturally produces corrective political action. In the Soviet case, hydrological measurements, salinity records, fisheries statistics, and climatic observations were collected systematically. Research institutes generated projections and circulated warnings through bureaucratic channels. The system did not lack information. On the contrary, it possessed a detailed empirical record of decline. Yet data did not automatically translate into policy reversal. The presence of measurement proved compatible with continued environmental degradation.

Denial in this context did not manifest as public rejection of scientific findings or overt claims that ecological decline was imaginary. Instead, it operated through prioritization, framing, and institutional filtering. Production quotas for cotton, regional economic commitments, and ideological narratives of modernization shaped decision-making hierarchies at every administrative level. Scientific warnings were acknowledged in reports and conferences, but they were ranked beneath economic objectives embedded in planning metrics. Within centralized structures, ministries were evaluated according to output figures, acreage under irrigation, and yield statistics rather than ecological sustainability indicators. Environmental risk became a secondary variable, discussed as a technical complication rather than a structural constraint. Even as hydrological data showed accelerating decline, the bureaucratic apparatus continued to function according to established performance measures. Denial functioned not as disbelief but as structured inaction, a system in which acknowledgment did not produce recalibration.

This pattern reveals a paradox of technocratic governance. A state capable of quantifying environmental decline may simultaneously lack mechanisms for integrating that knowledge into binding political constraints. Data can illuminate risk, but institutions determine whether risk alters behavior. In the Aral Sea basin, bureaucratic fragmentation diffused responsibility across agencies, reducing accountability for cumulative impact. Water management authorities focused on allocation efficiency, agricultural ministries on yield targets, and scientific institutes on documentation, each operating within discrete mandates. No institutional actor possessed both the authority and incentive to impose comprehensive limits on diversion. The architecture of decision-making insulated core economic priorities from ecological recalibration, even as warning indicators accumulated. Technocratic systems may generate sophisticated models of decline while remaining structurally committed to the policies producing it.

The broader implication is that environmental collapse in modern systems need not arise from ignorance. It can emerge from the coexistence of scientific clarity and institutional rigidity. When political legitimacy is anchored to growth and production, evidence of ecological harm may be incorporated into discourse without altering trajectory. The Aral Sea illustrates how denial adapts to data-rich contexts: it does not suppress measurement but absorbs it, treating degradation as a tolerable trade-off. In such systems, irreversibility is not the product of absent knowledge, but of structures that reward continuity even as warning indicators accumulate.

Modern Environmental Governance and Structural Risk

The Aral Sea’s collapse offers a framework for examining contemporary environmental governance beyond the Soviet case. Modern states possess far greater technological capacity, real-time data acquisition, and global scientific collaboration than existed during the height of river diversion in Central Asia. Satellite monitoring, climate modeling, and international research networks provide unprecedented clarity regarding ecological trends. Yet the structural challenge remains: whether institutions can translate measurement into restraint. The Aral case suggests that informational abundance does not automatically generate precautionary policy. Instead, governance systems must align incentives, authority, and accountability with ecological thresholds.

Contemporary environmental governance operates within complex political economies shaped by growth imperatives, energy demands, and geopolitical competition. As in the Soviet cotton system, economic priorities can dominate institutional agendas even when environmental risk is well documented. Regulatory agencies may collect extensive data while lacking enforcement authority or facing political pressure to moderate their findings. Democratic systems, while distinct from centralized planning regimes, can exhibit their own forms of structural inertia. Electoral cycles compress long-term ecological concerns into short-term campaign horizons, and partisan polarization can transform scientific consensus into political controversy. Industry lobbying and economic dependence on extractive sectors further complicate regulatory resolve. Even when environmental ministries articulate ambitious targets, implementation often depends on cooperation across departments whose mandates prioritize employment, revenue, or energy security. The result can be a layered system in which knowledge circulates widely but decisive action is diluted by competing priorities embedded within governance structures.

The concept of structural risk highlights how institutional design shapes environmental outcomes. When ministries or agencies are evaluated primarily on production, revenue, or energy output, ecological degradation can become a tolerated externality. Data may inform public debate without altering incentive structures that reward extraction or expansion. Risk becomes normalized as a cost of maintaining economic continuity. In this sense, modern governance shares a continuity with the Aral Sea case: the capacity to measure decline coexists with political reluctance to alter trajectories that sustain immediate material benefits. Structural risk emerges not from lack of knowledge but from misaligned priorities embedded within policy frameworks.

The Aral Sea demonstrates that ecological tipping points can be crossed gradually within systems that appear administratively competent. Modern environmental governance must be evaluated not only by the quality of its data but by its capacity for institutional adaptation and recalibration under pressure. Transparency and public reporting are necessary but insufficient if they are not paired with mechanisms that convert scientific thresholds into enforceable limits. Independent regulatory authority, cross-sector coordination, and integration of environmental costs into economic accounting become critical safeguards against incremental decline. Without such integration, even technologically advanced societies risk replicating the pattern of data-rich denial observed in the Aral basin. The lesson extends beyond any single case: ecological systems respond to cumulative pressure regardless of political system, and delay narrows the spectrum of viable response. Effective governance requires more than awareness; it demands structural alignment between knowledge and decision-making before mitigation gives way to irreversible damage control.

Conclusion: When Data Cannot Prevent Collapse

The Aral Sea stands as one of the clearest modern demonstrations that ecological collapse can unfold within a system saturated with information. Hydrological measurements, salinity records, fisheries statistics, climatic models, and satellite imagery accumulated alongside visible shoreline retreat and collapsing economic indicators. Scientific institutions generated projections that anticipated many of the consequences that later materialized, including salinization, fisheries loss, and regional climatic shifts. Reports circulated within ministries, conferences discussed potential trajectories, and technical memoranda documented accelerating decline. Yet knowledge alone did not alter the trajectory. The collapse proceeded not because warning signs were absent, nor because data were unavailable, but because institutional priorities remained anchored to production quotas, ideological narratives of modernization, and administrative continuity. The presence of data proved compatible with continued extraction. In this sense, the Aral Sea reveals a structural tension between empirical awareness and political recalibration that extends beyond its specific historical setting.

The tipping point, once crossed, transformed the range of possible responses. What might have been addressed through early restraint became a problem of fragmentation and partial stabilization. By the time recognition became politically unavoidable, restoration to the sea’s former equilibrium required levels of coordination and sacrifice that were institutionally improbable. Mitigation narrowed into damage control. The North Aral Sea’s partial recovery demonstrates that intervention can matter, yet it also underscores the scale of loss in the southern basin. Ecological systems, unlike policy narratives, do not reset easily once thresholds are exceeded.

The Aral case complicates optimistic assumptions about modern environmental governance. Technocratic states and contemporary democracies alike may possess sophisticated monitoring capacity while lacking structural mechanisms to translate knowledge into decisive constraint. When legitimacy and economic stability depend on growth, environmental signals can be incorporated rhetorically into sustainability frameworks without prompting substantive recalibration of underlying incentives. Denial in such contexts does not require rejection of science; it can take the form of delay, incrementalism, or reframing of degradation as manageable within existing growth models. Institutional fragmentation, competing jurisdictions, and economic dependence on resource extraction can dilute accountability even when evidence is unequivocal. Collapse emerges not from ignorance but from misalignment between scientific clarity and institutional will, a pattern that persists wherever measurement outpaces structural reform.

When data cannot prevent collapse, the lesson is neither anti-scientific nor fatalistic. It is structural. Measurement is necessary but insufficient. Ecological resilience depends on the capacity of political systems to recognize limits and realign incentives before irreversible thresholds are crossed. The Aral Sea reveals what occurs when recognition lags behind extraction and when acknowledgment arrives only after equilibrium has been lost. In an era defined by unprecedented environmental data, the central question is no longer whether warning signs are visible, but whether institutions can act upon them in time. The stakes are measured not only in declining water levels, but in the narrowing horizon between knowledge and no return.

Bibliography

- Glantz, Michael, ed. Creeping Environmental Problems and Sustainable Development in the Aral Sea Basin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Li, Qiang, et.al. “Investigate the Relationship between the Aral Sea Shrinkage and the Expansion of Cropland and Reservoir in Its Drainage Basins between 2000 and 2020.” International Journal of Digital Earth 14:6 (2021), 661-677.

- Micklin, Philip, N. V. Aladin, and Igor Plotnikov. The Aral Sea Disaster: The Devastation and Partial Rehabilitation of a Great Lake. Princeton: Springer, 2014.

- Peterson, Maya K. Pipe Dreams: Water and Empire in Central Asia’s Aral Sea Basin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Plotnikov, Igor S., et.al. “Past, Present and Future of the Aral Sea: A Review of its Fauna and Flora before and during the Regression Crisis.” Zoological Studies 12:62 (2023).

- Rockström, Johan, et al. “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Ecology and Society 14:2 (2009).

- Tainter, Joseph A. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- World Bank. North Aral Sea Development and Revitalization Project. World Bank Publications, 2019.

- Zonn, Igor S., and Michael Glantz. The Aral Sea Encyclopedia. Princeton: Springer, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.19.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.