The deification of Naram-Sin was neither a theological accident nor an isolated curiosity of ancient Mesopotamia. It represented a calculated reconfiguration of authority.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Divinity as Political Architecture

In the third millennium BCE, the kings of Mesopotamia ruled as chosen agents of the gods, but not as gods themselves. Their legitimacy derived from divine favor, ritual endorsement, temple patronage, and the maintenance of cosmic order, not from personal divinity. A ruler might be described as beloved of Inanna, shepherd of Enlil, or appointed by Shamash, yet he remained fundamentally human, dependent upon divine sanction rather than embodying it. Even the most powerful Sumerian and Akkadian kings framed their authority as stewardship under a higher sacred hierarchy. Within this established framework of mediated power, Naram-Sin of Akkad introduced a startling innovation. He did not merely claim to be favored by the gods; he declared himself a god. The move represented a decisive break from earlier traditions of kingship and altered the symbolic structure of authority in the ancient Near East. By collapsing the distance between the human ruler and the divine realm, he reshaped the metaphysical grammar of governance.

Naram-Sin’s deification did not emerge in a vacuum of religious enthusiasm or spontaneous theological development. It occurred within the context of imperial expansion, administrative strain, and internal unrest. The Akkadian Empire, forged by Sargon and expanded under his successors, governed a geographically vast and culturally diverse landscape that included Sumerian city-states, peripheral highland regions, and contested trade routes. Military victories brought prestige, but they also brought logistical challenges, tribute demands, and resentment among subject populations. Revolts and regional instability threatened imperial cohesion. Ideological consolidation became as important as military strength. A ruler who stood above ordinary humanity, sanctified rather than merely appointed, could transform obedience into reverence and rebellion into sacrilege. Deification provided a unifying symbolic framework that transcended local cults and civic loyalties. In this sense, divinity functioned not as mystical self-expression but as political architecture, engineered to stabilize an expanding and fragile imperial order.

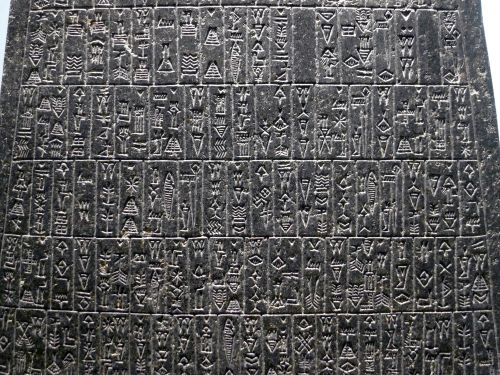

The iconography and inscriptions of Naram-Sin reinforce this interpretation. On the famous Victory Stele, he appears wearing the horned crown traditionally reserved for gods, ascending a mountain as celestial symbols hover above him. His name is written with the divine determinative, marking him linguistically as more than human. These were not incidental artistic flourishes. They were calculated signals embedded in the visual and textual language of power. By reconfiguring kingship as sacred presence rather than delegated authority, Naram-Sin fused the political and the cosmic in a single figure.

Naram-Sin’s self-deification was a strategic response to imperial pressures and institutional realities rather than an eruption of personal piety. Religious endorsement did not arise because he exemplified holiness; it arose because sacralizing authority stabilized governance. In elevating himself to divine status, Naram-Sin transformed the grammar of rule. The consequences of that transformation illuminate a broader historical pattern in which religious institutions endorse political leaders not for spiritual virtue, but for political usefulness.

The Akkadian Imperial Context: Expansion and Strain

The Akkadian Empire emerged in the twenty-fourth century BCE as the first durable territorial state in Mesopotamian history. Under Sargon of Akkad, a network of independent Sumerian city-states was brought under centralized rule, bound together by military force, administrative oversight, and the redistribution of resources. This was not merely a shift in political leadership; it was a transformation in scale and conception. Earlier Mesopotamian politics had been intensely local, with each city organized around its patron deity, its temple economy, and its own dynastic traditions. Sargon’s consolidation disrupted that equilibrium. Authority no longer resided exclusively within autonomous urban polities but radiated outward from an imperial center that claimed supremacy over multiple cultic and civic identities. The result was a new political reality that required continuous management of distant territories, tribute systems, and diverse populations. Imperial kingship demanded a broader ideological vocabulary than city-state rule, one capable of explaining why a ruler from Akkad could legitimately command cities with their own ancient gods and traditions.

Expansion brought prestige and wealth, yet it also generated strain. Conquest created obligations: garrisons had to be maintained, governors installed, supply lines secured, and subject cities monitored. The empire stretched across regions that differed in language, cult practice, and economic structure. Integrating these territories required more than battlefield success. It required administrative coherence and ideological framing capable of persuading local elites that imperial rule was not merely imposed but inevitable. Without such framing, rebellion remained a constant possibility.

The reign of Naram-Sin intensified these pressures. Inscriptions from his rule record campaigns against highland groups and internal revolts, suggesting that imperial control was neither uncontested nor stable. The rhetoric of victory often masks the persistence of resistance, yet the very frequency of military reporting indicates recurring instability. Campaigns had to be renewed because subjugation was provisional. Peripheral regions resisted taxation and oversight; urban centers guarded their autonomy and cultic traditions. In such an environment, the emperor’s authority could not rest solely on personal charisma or inherited prestige. It required reinforcement through symbols that transcended regional loyalties and reframed resistance as cosmic disorder rather than political dissent. When opposition could be portrayed not simply as rebellion against a king but as defiance against divinely ordered hierarchy, suppression acquired moral weight.

Economic dynamics compounded these challenges. The Akkadian state depended upon flows of tribute, agricultural surplus, and trade goods to sustain its court and military apparatus. Temples, long central to urban economies, now operated within an imperial framework that linked religious institutions to royal administration. Offerings, landholdings, and labor obligations intersected with palace oversight in increasingly complex ways. The integration of temple wealth into broader state mechanisms blurred the boundaries between sacred and secular authority, transforming economic coordination into ideological partnership. As the palace expanded its reach, the ideological justification for centralized control became increasingly significant. Stability required not only bureaucratic efficiency but also symbolic alignment between priesthood and crown. The consolidation of economic power intensified the need for a unifying narrative that elevated the king beyond ordinary political rivalry.

Naram-Sin’s self-deification appears less as an act of theological audacity and more as a response to structural vulnerability within the imperial context of expansion and strain. The empire required a unifying principle powerful enough to command loyalty across cities and regions. By elevating himself above ordinary kingship, Naram-Sin provided such a principle. Divinity offered a language of inevitability and sacred necessity that ordinary political authority could not. In a realm stretched thin by ambition and resistance, sacral kingship functioned as reinforcement for a system under pressure.

Breaking Tradition: The Innovation of Living Divinity

Before Naram-Sin, Mesopotamian kingship operated within a clear theological hierarchy. Rulers were appointed by gods, loved by gods, and sustained by gods, but they remained mortal intermediaries. Even powerful figures such as Sargon and Rimush described themselves as chosen instruments rather than embodiments of divinity. The king’s duty was to maintain justice, defend the land, and preserve ritual order under divine oversight. This distinction preserved a structural separation between the sacred realm and political authority. Naram-Sin’s claim to divinity disrupted that boundary. By presenting himself not merely as divinely favored but as divine, he reconfigured the metaphysical assumptions that undergirded kingship.

The innovation was not subtle. In inscriptions from his reign, Naram-Sin’s name is preceded by the divine determinative, a sign traditionally reserved for gods. This was more than an honorific flourish. In Mesopotamian writing, determinatives signaled categorical identity. To place the divine marker before a ruler’s name linguistically reclassified him. The transformation of grammar signaled a transformation of status. Authority was no longer mediated through divine favor; it was embodied in the king himself. The language of administration became a vehicle for theological change.

Iconography reinforced the shift. On the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, the king is depicted wearing the horned crown, a symbol conventionally associated with gods. He towers above his soldiers and enemies alike, ascending a mountainous landscape under celestial symbols. The composition does not merely celebrate victory; it elevates the king visually into a cosmic sphere. The scale of his figure relative to others signals hierarchical transcendence, not simply military superiority. The horned helmet, previously confined to divine iconography, collapses the visual boundary between deity and monarch. Even the upward movement of the scene, with Naram-Sin climbing toward astral emblems, suggests proximity to celestial authority. Art here functions as theological argument. The stele does not describe doctrine in prose; it renders doctrine visible. By embedding divine attributes in the public imagery of conquest, the regime normalized the idea that imperial expansion was an expression of sacred power embodied in the king himself.

This redefinition of kingship altered the logic of obedience in profound ways. A ruler appointed by the gods could, in theory, fail in his duties and lose divine favor. His authority remained conditional upon continued alignment with divine will. A ruler who was himself divine removed that mediating layer. Obedience no longer flowed through the gods to the king; it flowed directly to the king as sacred being. Resistance could be framed not merely as political dissent but as theological rebellion. The conceptual stakes were raised. Legal, military, and administrative authority became infused with sacral inviolability. In practical terms, this shift strengthened the ideological armor of the throne. It did not eliminate resistance, but it altered how resistance was understood and justified. The king’s person became the axis around which cosmic and political order revolved, tightening the bond between imperial governance and sacred structure.

The innovation also marked a turning point in Mesopotamian political thought. Later traditions would interpret Naram-Sin’s reign ambivalently, associating it with hubris and divine punishment in texts such as the Curse of Agade. Yet even such retrospective critique acknowledged the magnitude of his claim. Living divinity was remembered precisely because it broke precedent. Whether celebrated or condemned, it demonstrated that kingship could be reimagined as sacred presence rather than delegated authority. In that reimagining lay the strategic potential of deification as a tool of governance.

Strategic Sacralization: Religion as Governance Tool

If Naram-Sin’s claim to divinity represented theological innovation, its durability depended upon institutional adoption. Religion in Mesopotamia was not a private sphere but a structural component of political life. Temples controlled land, labor, and surplus; priesthoods mediated ritual, calendrical observance, and civic identity. To sacralize the king was to integrate royal authority into the existing religious infrastructure. Divinity was not merely proclaimed; it was operationalized through ritual recognition, temple inscription, and administrative language. Once embedded within institutional practice, the king’s divine status became part of the machinery of governance.

This sacralization altered the mechanics of obedience in ways that extended beyond symbolic reverence. Political authority ordinarily relies upon force, custom, negotiated loyalty, and the expectation of reciprocal obligation. Sacred authority introduces an additional dimension: moral obligation framed as cosmic necessity. When the ruler is divine, loyalty is no longer simply compliance with law but alignment with sacred order. The administrative command acquires theological resonance, and the act of obedience can be interpreted as participation in divine structure. Taxation, conscription, tribute collection, and labor mobilization become embedded in a narrative that transcends political contingency. In such a system, dissent risks classification not merely as defiance of the state but as disruption of cosmic balance. Even if individuals resisted internally, the public language available for framing that resistance narrowed. The fusion of sacred and administrative categories fortified authority at the level of meaning as well as enforcement.

The strategic dimension of this fusion becomes clearer when viewed against the background of imperial fragility. Multiethnic empires require symbols that transcend local identities. A king elevated above ordinary humanity can function as a unifying figure whose authority does not depend upon any single city’s patron deity. By embodying divinity, Naram-Sin positioned himself as a supra-local sacred presence. His divinity was not tied exclusively to one cult center but projected across the empire. This broadened symbolic reach strengthened the center’s ideological leverage over diverse territories.

Sacralization also reshaped the moral framing of coercion. Military campaigns and suppression of revolt could be presented as the enforcement of divine will rather than mere assertion of power. Victory inscriptions already described conquest as divinely sanctioned; deification intensified that rhetoric by collapsing the distance between divine sanction and royal action. When the king’s person becomes sacred, opposition risks classification as impiety. Even if subjects did not internalize this framing uniformly, the ideological structure narrowed the discursive space in which resistance could be legitimized. Power gained an additional layer of justification.

The partnership between palace and temple further reinforced this system in practical and institutional terms. Priestly authorities oversaw ritual calendars, temple estates, and economic redistribution networks that were integral to urban life. Their cooperation was essential for maintaining social continuity. Aligning with a deified king ensured continued patronage, protection, and integration within the imperial administrative structure. Recognition of Naram-Sin’s divinity was not merely an act of devotional affirmation but also an act of strategic alignment. By embedding the king within the sacred hierarchy, religious institutions preserved their relevance within an expanding imperial framework. The relationship was reciprocal. The throne gained sacral legitimacy, while the temple retained influence, resources, and proximity to executive power. In this mutual reinforcement, divinity functioned as a bridge between sacred authority and political centralization.

Strategic sacralization did not eliminate the structural tensions of empire, nor did it guarantee stability in the face of rebellion or ecological stress. What it provided was an interpretive scaffold that elevated royal authority above ordinary political contestation. Divinity became a language of inevitability, transforming governance into sacred mandate and rendering imperial expansion as expression of cosmic design. This ideological shift altered how power was imagined and narrated, both by rulers and by institutions that benefited from alignment. Religion in this context was not reduced to propaganda, yet it was unmistakably deployed as governance tool. In Naram-Sin’s reign, sacred narrative and imperial administration converged in a manner that reveals the pragmatic potential of theology. The episode illustrates how sacral categories can be mobilized to stabilize authority when conventional political mechanisms alone appear insufficient.

Priestly Institutions and Power Alignment

In Mesopotamian cities, temples were not marginal spiritual centers but core institutional anchors of economic and social life. They owned agricultural estates, supervised irrigation networks, managed dependent laborers, and maintained storehouses that redistributed grain, textiles, and livestock. Temple complexes functioned as administrative hubs where scribes recorded transactions and coordinated production. Priests were not merely ritual officiants invoking divine favor; they were embedded in the economic architecture of urban society. Their authority rested as much on logistical competence as on liturgical performance. Any transformation in kingship required negotiation, whether explicit or implicit, with priestly institutions whose cooperation was essential to civic stability. Deifying the king did not bypass religious authority; it repositioned it within a reconfigured hierarchy in which sacred and administrative power became increasingly intertwined.

The elevation of Naram-Sin to divine status depended upon ritual acknowledgment. Temples inscribed his name with the divine determinative and integrated his cultic presence into ceremonial life. Such acts were not merely symbolic gestures imposed from above. They required institutional participation. Priestly elites had to incorporate the king’s divinity into liturgical practice and temple documentation. By doing so, they affirmed a theological shift that bound their authority more closely to imperial rule. Religious recognition provided durability to what might otherwise have remained rhetorical innovation.

This alignment can be understood in pragmatic terms. Imperial expansion brought increased flows of tribute and wealth, much of which intersected with temple economies. Conquered regions supplied raw materials, agricultural produce, and labor that entered redistribution networks in which temples played central roles. Priestly administrators benefited from predictable tribute streams and from imperial protection of trade routes and agricultural infrastructure. Supporting the sacral elevation of the king reinforced the stability upon which temple prosperity depended. Endorsement of divine kingship strengthened the political framework that sustained religious institutions materially. The sacral hierarchy and the political hierarchy became mutually reinforcing structures, each legitimizing the other while sharing in the advantages of centralized control.

Priestly alignment with a deified ruler carried risks. If the king’s authority faltered, the institutions that had sanctified him could share in the consequences. Later Mesopotamian literature, including narratives such as the Curse of Agade, reflects retrospective unease with excessive royal hubris. The memory of divine kingship was not uniformly celebratory. Priestly participation in sacralizing authority involved calculated judgment about present stability versus potential future fallout. Alignment was strategic rather than naïvely devotional.

The partnership between temple and throne also altered the balance of symbolic power. When the king embodied divinity, priestly mediation shifted from interpreting the will of external gods to sustaining the cult of a living ruler. This shift required ritual adaptation. Festivals, offerings, and dedicatory inscriptions increasingly acknowledged the king’s sacred status alongside traditional deities. Priests became custodians of a cult that fused political loyalty with religious expression. Rather than diminishing priestly relevance, this development embedded their authority within the very process that legitimized the monarch. By supervising the rites that affirmed royal divinity, priestly elites retained influence over how sacred kingship was performed and understood. The collaboration was not one-sided; it institutionalized a reciprocal dependency between throne and temple.

Priestly institutions did not endorse Naram-Sin’s divinity because of demonstrated holiness or moral transformation. They endorsed it because it aligned sacred authority with political stability in a manner advantageous to both palace and temple. Religious recognition functioned as institutional calculus. By integrating the ruler into the sacred order, priests preserved their influence within an expanding imperial framework. The episode illustrates how religious authority can align with executive power not as passive submission but as negotiated partnership grounded in usefulness rather than piety.

Deification and Internal Instability

The intensification of royal divinity during Naram-Sin’s reign coincided with evidence of internal unrest. Akkadian inscriptions recount campaigns not only against distant highland peoples but also against coalitions of Mesopotamian cities, indicating that imperial authority was repeatedly tested. While royal texts emphasize victory and subjugation, the recurrence of such campaigns suggests that compliance was neither automatic nor permanent. Conquest required reinforcement, and loyalty had to be renewed through demonstration of force. Revolts did not erupt in a vacuum; they signaled resistance to centralization, taxation, and imposed authority within cities long accustomed to local autonomy. In this context, deification can be interpreted as a response to vulnerability rather than mere assertion of grandeur. Sacred kingship provided ideological reinforcement at moments when coercive mechanisms alone were insufficient, elevating royal authority into a sphere less accessible to ordinary political negotiation.

Internal instability threatened more than territorial control. It endangered the narrative of inevitability upon which imperial authority depended. An empire that must repeatedly reconquer its own subjects exposes the limits of its administrative integration. By elevating himself to divine status, Naram-Sin reframed opposition as deviation from sacred order rather than contestation of political arrangements. Rebellion could be represented as sacrilege. This shift did not prevent revolt, but it redefined its moral valence. The king’s authority was no longer negotiable within civic tradition; it was anchored in cosmic hierarchy.

Environmental and economic pressures may have compounded these tensions. Scholars have long debated the role of climatic fluctuation and resource strain in the eventual weakening of the Akkadian Empire. Even without assigning determinative weight to ecological explanations, it is clear that imperial overextension created administrative burdens that strained cohesion. Deification in such circumstances functioned as symbolic consolidation. When material stability faltered, sacral narrative offered continuity. The projection of divine permanence countered the perception of political fragility.

The later literary tradition reflects awareness of this precarious balance. The Curse of Agade portrays Naram-Sin as a ruler whose actions provoked divine displeasure, resulting in catastrophe for the city of Akkad. Although composed after his reign and shaped by theological hindsight, the text preserves cultural memory of tension surrounding divine kingship. It dramatizes a king who oversteps proper ritual boundaries and suffers divine retaliation, thereby restoring the supremacy of traditional gods over mortal ambition. Such narratives reveal that Naram-Sin’s deification was remembered as disruptive, not routine. The story does not deny his power; it interrogates the consequences of conflating royal authority with divinity. In doing so, it exposes an underlying anxiety: if a ruler claims sacred status and the empire still collapses, how is cosmic order to be explained? The answer offered by later tradition is corrective theology, but the very need for correction testifies to the destabilizing potential of living divinity.

The convergence of sacralization and instability underscores the strategic dimension of living divinity. Deification was not a guarantee of political success, nor did it insulate the empire from structural pressures. It functioned as ideological armor, strengthening authority during moments of strain. Yet the very need for such reinforcement suggests that imperial cohesion required constant maintenance. Naram-Sin’s divine status both reflected and attempted to manage the insecurities of rule in an expanding, contested empire.

Comparative Political Theology: Useful Holiness

The example of Naram-Sin invites a broader interpretive question: when religious institutions affirm a ruler’s sacred status, are they responding to demonstrated holiness or to political necessity? In the Akkadian world, divinity functioned as a tool of governance, strengthening executive authority under conditions of expansion and strain. The sacralization of the king did not arise from mystical charisma alone; it emerged within a matrix of institutional needs, administrative pressures, and imperial ambition. When temples inscribed the divine determinative before Naram-Sin’s name, they were participating in a transformation of authority that had tangible political consequences. This pattern suggests that sacral endorsement can operate less as recognition of spiritual virtue and more as strategic alignment. Political theology, in this sense, becomes an architecture of usefulness, structuring legitimacy in ways that reinforce stability. Sacred language legitimizes power not because the ruler embodies transcendent morality, but because sacralization stabilizes institutional arrangements and reframes obedience as sacred duty.

Comparative political theology reveals recurring examples of this logic. Across different historical contexts, religious authorities have framed leaders as divinely appointed, providentially guided, or specially chosen at moments when institutional interests converged with executive ambition. Such framing does not necessarily imply insincerity; belief and pragmatism often intertwine. Yet the pattern demonstrates that sacral language frequently amplifies power during periods of contestation. The alignment of altar and throne becomes mutually reinforcing when both perceive benefit in consolidation. The ruler gains moral elevation, and religious institutions secure access, protection, or policy influence.

In contemporary American politics, a similar dynamic can be observed in the overwhelming support of President Donald Trump by white evangelical leadership during his first term and into his second term beginning in 2025. Trump’s personal conduct and rhetorical style have frequently diverged from traditional evangelical moral teachings. Nevertheless, many evangelical leaders have framed him as divinely appointed, providentially chosen, or instrumentally necessary for advancing policy priorities such as judicial appointments, abortion restrictions, and religious liberty claims. In this context, sacred language functions less as affirmation of personal piety than as endorsement of political utility. The logic parallels that of ancient sacralization: usefulness can outweigh conformity to religious ideal.

This comparison does not collapse historical difference, nor does it reduce faith to mere calculation. Rather, it underscores a structural pattern in which religious institutions may sanctify authority when doing so protects or advances institutional aims. Naram-Sin’s deification and modern evangelical political endorsement both illustrate how sacred narratives can fuse with executive power under conditions of perceived necessity. In each case, holiness becomes useful, and usefulness becomes holy. The convergence reveals that political theology often operates at the intersection of belief, stability, and institutional survival.

Modern Parallel: Evangelical Endorsement and Instrumental Legitimacy

The endorsement of Trump by large segments of white evangelical Christians presents a contemporary case of instrumental sacralization. Trump has not been widely regarded as a model of evangelical devotional life. His public record, rhetorical style, and personal conduct have frequently diverged from the moral expectations historically emphasized within evangelical teaching. Yet despite this divergence, many evangelical leaders and voters have framed him as divinely appointed, providentially protected, or uniquely chosen for the present political moment. The language of sacred selection has functioned less as testimony to personal piety than as affirmation of political alignment.

The core of that alignment has centered on policy outcomes. Judicial appointments, especially to the Supreme Court and federal judiciary, have been understood as decisive for abortion law, religious liberty claims, and broader cultural battles. Executive actions perceived as favorable to evangelical priorities have reinforced the narrative that Trump serves as an instrument of divine purpose. In this framing, usefulness becomes theological evidence. The logic mirrors ancient patterns in which sacral language elevates a ruler whose political actions advance institutional aims. Personal virtue becomes secondary to perceived effectiveness.

Religious rhetoric surrounding Trump has frequently invoked biblical archetypes of imperfect leaders used by God to accomplish divine plans. Such comparisons allow theological reconciliation between moral irregularity and political endorsement. The analogy does not require the leader to embody holiness; it requires only that he be positioned as necessary within a providential framework. This rhetorical strategy transforms political loyalty into an expression of faithfulness. Institutional support, in turn, strengthens access to executive influence and reinforces the perception that sacred and political authority operate in tandem.

This dynamic does not suggest uniformity of belief among all evangelicals, nor does it reduce religious conviction to mere opportunism. It does, however, reveal a structural similarity to earlier episodes of sacralized power. Just as Naram-Sin’s divinity aligned temple authority with imperial governance, modern evangelical endorsement aligns religious identity with executive authority when political usefulness is at stake. In both contexts, sacred legitimacy functions as reinforcement for power under conditions of cultural or political contestation. Holiness becomes defined not by devotional conformity but by strategic alignment with institutional priorities.

Conclusion: When Divinity Serves Power

The deification of Naram-Sin was neither a theological accident nor an isolated curiosity of ancient Mesopotamia. It represented a calculated reconfiguration of authority at a moment when empire required ideological reinforcement. By collapsing the boundary between the sacred and the political, Naram-Sin transformed kingship into sacred presence. His divinity did not eliminate instability, nor did it prevent eventual imperial decline. It did, however, demonstrate the potency of sacral language in fortifying executive power during periods of expansion and strain. Divinity became architecture, shaping how obedience was imagined and justified.

The participation of priestly institutions reveals the reciprocal dimension of this transformation. Religious authorities did not simply submit to royal innovation; they incorporated it into ritual and administrative practice because alignment offered stability and influence. Sacral endorsement functioned as institutional strategy. The temple gained proximity to power, and the throne gained theological elevation. In this convergence, holiness operated less as moral evaluation and more as political reinforcement. Sacred status was conferred because it served governance.

The modern parallel underscores the persistence of this structural pattern. When religious communities frame political leaders as providentially appointed despite evident tensions with doctrinal ideals, the logic resembles ancient sacralization. In the case of President Donald Trump’s sustained support among white evangelical leadership into his second term beginning in 2025, sacred language has frequently functioned as interpretive shield for political alignment. Appeals to biblical archetypes of flawed but divinely used rulers allow moral dissonance to be reframed as providential necessity. Policy outcomes, particularly those involving judicial appointments and cultural legislation, are elevated as evidence of divine instrumentality. In this formulation, usefulness becomes the organizing principle of legitimacy. The leader is endorsed not because he embodies spiritual virtue in exemplary form, but because he advances institutional priorities perceived as urgent or existential. Sacred narrative then stabilizes political alignment, translating strategic calculation into theological affirmation and reinforcing the bond between religious identity and executive authority.

The fusion of sacred legitimacy and executive authority reveals a recurring dynamic in political theology across millennia. Divinity, or its rhetorical equivalent, can serve as shield, amplifier, and stabilizer for power. Whether in Akkadian Mesopotamia or modern America, the sanctification of authority often reflects institutional need as much as devotional conviction. When divinity serves power, holiness becomes useful, and usefulness acquires the aura of holiness. The pattern does not negate genuine belief, but it clarifies how sacred language can function as governance tool when political order seeks reinforcement.

Bibliography

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Du Mez, Kristin Kobes. Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. New York: Liveright, 2020.

- Epphimer, Melissa. “Assembling King and State: The Statues of Manishtushu and the Consolidation of Akkadian Kingship.” American Journal of Archaeology 114:3 (2010), 365-380.

- —-. Exemplars of Kingship: Art, Tradition, and the Legacy of the Akkadians. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Fea, John. Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018.

- Foster, Benjamin R. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. Bethesda: CDL Press, 2005.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

- Jones, Robert P. The End of White Christian America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. History Begins at Sumer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1956.

- Liverani, Mario. The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Pew Research Center. “White Evangelicals Remain among Trump’s Strongest Supporters, but They’re Less Supportive than a Year Ago.” Feb. 9, 2026.

- Steinkeller, Piotr. “The Administrative and Economic Organization of the Ur III State.” In The Organization of Power: Aspects of Bureaucracy in the Ancient Near East, edited by McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs. Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1991.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- van Dijk-Coombes, Renate Marian. “Revisiting the ‘kriegerischer Gott’ of the Akkadian Period.” Religions 14:9 (2023).

- Winter, Irene J. “The King and the Cup: Iconography of the Royal Presentation Scene in Ur III Art.” In Studies in the History of Art. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1987.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.20.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.