Constantine’s reign illustrates how religious transformation at the highest level of power can operate as strategic realignment rather than pure devotional rupture.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Conversion and Power

Few figures in late antiquity have been more persistently framed as symbols of religious transformation than Constantine the Great. Traditional narratives portray him as the emperor who turned from paganism to Christianity after a visionary experience before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE, inaugurating a new era in Roman history. Yet the historical Constantine resists such simplicity. His so-called conversion unfolded within the brutal context of civil war, dynastic rivalry, and imperial consolidation. Rather than marking a sudden abandonment of Roman religious culture, Constantine’s embrace of Christianity occurred alongside the continuation of traditional imperial practices. The relationship between faith and power in his reign was less a rupture than a recalibration.

The Roman Empire had long fused religious symbolism with political authority. Emperors bore sacred titles, presided over rituals, and were embedded in the imperial cult. Constantine inherited this sacralized model of rule. What changed under his authority was not the existence of religious politics but the religious partner. Christianity, previously marginalized and at times persecuted, became a beneficiary of imperial favor. The legalization of Christian worship and restoration of confiscated property signaled a profound shift in status. Yet the emperor did not immediately sever ties with traditional Roman religious forms. Coins bearing Sol Invictus continued to circulate, and Constantine retained the title of Pontifex Maximus. His religious posture remained layered and politically adaptive.

Constantine’s delayed baptism, undertaken only on his deathbed in 337 CE, further complicates the narrative of wholehearted spiritual conversion. In late antique Christian theology, baptism washed away sin and marked full entry into the faith. By postponing it, Constantine preserved the ability to exercise imperial violence and political pragmatism without the constraints that might accompany earlier initiation. This decision suggests that faith, while significant, was carefully managed within the demands of rulership. Christianity was embraced, but not in a manner that subordinated imperial authority to ecclesiastical discipline.

Constantine’s relationship with Christianity is best understood as an alliance in which religion functioned as imperial technology. Christian leaders hailed him as divinely chosen not solely because of devotional sincerity, but because imperial backing offered legal protection, wealth, and unprecedented influence. Faith did not disappear under Constantine, but it was integrated into statecraft. Conversion and power became mutually reinforcing categories. In the fusion of cross and empire, the sacred did not conquer politics; it was recruited to stabilize it.

The Roman Religious Landscape before Constantine

Before Constantine’s rise, the Roman Empire operated within a religious framework defined by plurality, adaptability, and political integration. Roman religion was not a system of exclusive belief but a network of rituals, cults, and civic obligations embedded in public life. Participation in traditional rites signaled loyalty to the state as much as reverence for particular deities. The pax deorum, the peace of the gods, depended upon correct ritual performance rather than doctrinal uniformity. Religion and governance were inseparable, not because Rome enforced theological conformity, but because public worship affirmed civic order.

Imperial authority had long been sacralized through established precedent. The imperial cult, developed in the early Principate, allowed subjects to honor the emperor and the genius of Rome in ways that reinforced loyalty without necessarily displacing traditional gods. Emperors were not worshiped as transcendent creators but were venerated as embodiments of Rome’s stability and divine favor. Titles, rituals, and temple dedications integrated the emperor into sacred life across the provinces. Political allegiance and religious observance intersected in institutionalized form, creating a model in which executive authority already possessed sacred dimensions.

The third century intensified this fusion of religion and power. Military crisis, economic instability, and repeated civil wars destabilized imperial cohesion. Emperors increasingly emphasized divine support to legitimate their rule. Solar symbolism, especially the cult of Sol Invictus, gained prominence under emperors such as Aurelian. Divine patronage offered reassurance in an era marked by fragmentation and usurpation. Religious imagery functioned as stabilizing rhetoric, projecting continuity amid volatility.

The so-called Great Persecution under Diocletian in the early fourth century must be understood within this context of political consolidation. Christianity, with its refusal to participate in certain civic rituals and imperial cult practices, posed a challenge not simply because it was theologically distinct, but because it disrupted ritual participation understood as civic loyalty. Roman governance relied upon visible conformity to shared rites as a marker of allegiance. When Christians declined to sacrifice to the gods or to the genius of the emperor, their abstention was interpreted as civic withdrawal. The persecution aimed at restoring ritual compliance rather than eradicating theological ideas. Edicts targeted clergy, required sacrifice, and demanded public demonstration of loyalty. The objective was unity expressed through shared practice. In this sense, the state’s confrontation with Christianity reflected anxiety over cohesion rather than fear of doctrinal deviation. Religious conformity functioned as political glue in a fractured empire.

Christianity had grown into a substantial institutional network by the early fourth century. Urban congregations were organized under bishops who exercised authority over clergy, managed charitable distributions, adjudicated disputes, and maintained communication with other communities across provincial boundaries. Synods and correspondence fostered doctrinal dialogue and collective identity beyond local cities. This transregional structure paralleled imperial administrative frameworks and created lines of influence that extended across the Mediterranean. Far from being an isolated sect, Christianity had developed mechanisms of coordination and leadership that mirrored, and at times rivaled, imperial organization. Its visibility made it difficult to suppress completely, and its internal coherence made it a potentially valuable ally for a ruler seeking stability. The same features that rendered it suspect during persecution rendered it attractive under a regime pursuing consolidation.

Constantine inherited this religious landscape of sacralized emperorship, institutional Christianity, and fragile unity. The empire already understood how to integrate religious symbolism into political authority. What remained open was which religious network would most effectively support imperial consolidation. Christianity’s structure, moral language, and growing demographic presence positioned it as a viable candidate. Constantine’s later alignment with the church did not invent political religion; it redirected an existing pattern toward a new institutional alliance.

The Edict of Milan and the Legalization of Christianity

The Edict of Milan in 313 CE did not establish Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, but it transformed its legal standing. Issued jointly by Constantine and Licinius after their political accommodation, the edict proclaimed religious toleration throughout the empire and ordered the restoration of confiscated Christian property. Its language emphasized freedom of worship for all citizens, framing the measure as a means of securing divine favor for the stability of the state. Rather than privileging Christianity exclusively, the policy sought to remove religious grievance as a source of unrest. In doing so, Constantine repositioned Christianity from persecuted minority to legally protected institution.

The political context of the edict was decisive. Constantine had emerged victorious in the western civil wars and required consolidation of authority across contested territories that had recently endured military upheaval and administrative disruption. Religious toleration served as an instrument of pacification, signaling a break from the coercive policies of Diocletian while also cultivating support from Christian communities that had suffered confiscations, imprisonment, and execution. Restoring confiscated church property was not merely an act of restitution; it materially strengthened ecclesiastical infrastructure by returning buildings, lands, and financial assets essential to Christian communal life. These restitutions signaled that imperial favor could now replace imperial hostility. By aligning himself with a network that spanned urban centers and provincial boundaries, Constantine gained access to an organized constituency capable of reinforcing imperial legitimacy. Legal accommodation doubled as political investment, embedding Christian leadership within the broader architecture of imperial consolidation.

The legalization of Christianity also enhanced the administrative reach of the imperial state. Bishops, already functioning as local leaders within their communities, became intermediaries between imperial authority and urban populations. Their moral authority and communication networks provided channels through which imperial policy could be disseminated and interpreted. Christianity’s institutional coherence complemented imperial governance. Legal recognition did not subordinate the church entirely to the state, but it integrated ecclesiastical structures into the broader fabric of imperial administration.

The Edict of Milan illustrates how legalization functioned as strategic accommodation rather than simple spiritual declaration. Constantine did not abandon the pluralistic religious framework of Rome; he recalibrated it in a manner that expanded his coalition of support. By removing legal barriers and restoring property, he transformed Christianity into a partner of imperial stability without formally displacing other cults. The alliance provided Christians with security, wealth, and social prestige while furnishing the emperor with institutional reinforcement and moral rhetoric capable of legitimizing rule. Legal toleration created conditions for deeper entanglement between church and state, opening pathways for imperial involvement in doctrinal disputes and ecclesiastical organization. What began as a policy of toleration laid the groundwork for Christianity’s elevation within imperial hierarchy, demonstrating that accommodation could serve as a mechanism of consolidation.

Selective Christianity: Continuity with Roman Power Practices

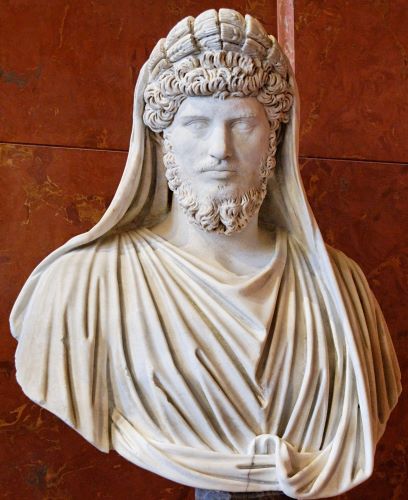

Constantine’s public embrace of Christianity did not erase the symbols and structures of traditional Roman power. Instead, his religious posture exhibited continuity layered with adaptation. Even after the Edict of Milan, imperial coinage continued to feature Sol Invictus imagery for several years, reflecting the persistence of solar symbolism within imperial iconography and its resonance with themes of divine favor and victory. The emperor’s portraiture did not immediately abandon established visual language but gradually incorporated Christian associations alongside traditional motifs. Constantine retained the title of Pontifex Maximus, the chief priestly office in Roman religion, and did not dismantle the ritual framework that had long bound emperor and sacred order together. Christianity entered an existing political system already saturated with sacral authority; it did not replace that system wholesale. Rather, it was layered onto structures that had long fused divinity and sovereignty, reinforcing rather than displacing the emperor’s elevated status.

This selective posture reveals a ruler operating within the constraints of imperial expectation. The Roman emperor was not merely a political executive but a custodian of religious tradition. Abrupt abandonment of long-standing cultic symbols risked alienating constituencies still embedded in traditional worship. Constantine pursued gradual transformation rather than sudden rupture. Christian patronage coexisted with continued engagement in Roman ceremonial life. The emperor’s identity became religiously hybrid, signaling favor toward Christianity while maintaining continuity with established structures of legitimacy.

The continuity extended beyond symbolism to institutional practice. Constantine maintained the hierarchical court culture and autocratic decision-making characteristic of the Dominate, preserving the ceremonial distance and bureaucratic machinery that defined late Roman governance. Imperial edicts continued to emanate from a centralized authority, and court rituals reinforced the emperor’s quasi-sacral presence before officials and petitioners. Monumental building projects, including churches, functioned within the broader tradition of imperial benefaction that had long tied architecture to legitimacy. Christianity was incorporated into this framework as an additional layer of authority rather than as a rival source of moral supremacy. Bishops gained influence through imperial favor, yet the emperor asserted his right to intervene in ecclesiastical disputes and doctrinal controversies. Sovereignty remained firmly anchored in imperial office. Religious alignment strengthened the throne; it did not subordinate it.

Delayed baptism underscores this calculated balance. In late antique understanding, baptism conferred spiritual rebirth and remission of sin. By postponing the rite until shortly before his death in 337 CE, Constantine preserved flexibility in the exercise of imperial violence and coercion. Military campaigns, executions, and political maneuvering continued throughout his reign. Baptism at life’s end allowed him to affirm Christian identity without submitting earlier to the moral expectations associated with full ecclesiastical membership. The timing reflects management of faith within the imperatives of rule.

Selective Christianity functioned as adaptive statecraft rather than simple personal transformation. Constantine did not convert into a private believer detached from imperial obligation; he integrated Christian affiliation into the grammar of Roman power in a manner calibrated to preserve authority. Traditional symbols were not immediately discarded but gradually reinterpreted, allowing continuity to mask transformation. The emperor’s religious posture remained instrumental and layered, demonstrating that the alliance between cross and crown emerged through negotiation rather than sudden doctrinal revolution. Christianity was not imposed upon the empire as a moral corrective to imperial excess; it was woven into an already sacralized political fabric, expanding the symbolic repertoire of sovereignty while safeguarding executive supremacy.

Christian Leadership and Imperial Patronage

Constantine’s alliance with Christianity cannot be understood solely from the imperial perspective. It must also be examined from the vantage point of Christian leadership. By the early fourth century, bishops had become central figures within urban Christian communities, exercising authority over doctrine, discipline, charity, and liturgical life. Yet their institutional position remained vulnerable under fluctuating imperial policy. The sudden shift from persecution to patronage transformed the structural landscape of Christian leadership. Imperial favor offered security, visibility, and resources on a scale previously unimaginable.

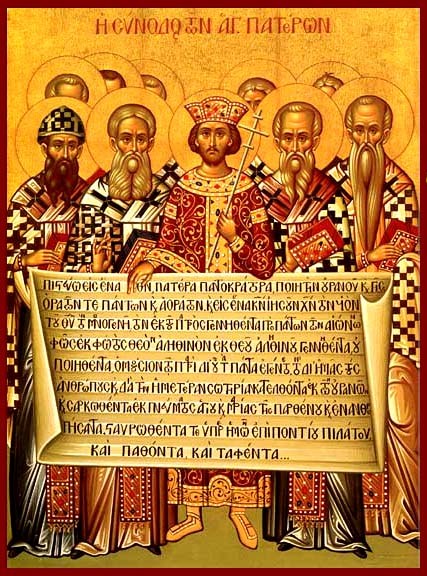

One of the most significant markers of this new relationship was Constantine’s involvement in the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. The council was convened to address the Arian controversy, a theological dispute concerning the nature of Christ and his relationship to the Father. Constantine did not approach the matter as a detached observer or merely as a pious Christian seeking doctrinal clarity. He understood that theological division threatened imperial unity. By funding travel for bishops across the empire, presiding ceremonially, and urging consensus, he signaled that ecclesiastical coherence had become a matter of state stability. The emperor’s presence lent political weight to theological deliberation, transforming what might have remained regional disputes into empire-wide decisions. For bishops, imperial sponsorship elevated ecclesiastical authority onto a broader political stage, reinforcing their institutional prominence while simultaneously binding their deliberations to imperial expectations of unity.

Imperial patronage extended beyond councils and doctrinal disputes. Constantine granted land to churches, funded the construction of monumental basilicas in Rome, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, and conferred legal privileges upon clergy. Exemptions from certain civic obligations enhanced the social standing of Christian leaders and distinguished them from other civic officials. Episcopal courts increasingly received imperial recognition in matters of arbitration, allowing bishops to function as judicial authorities whose decisions carried social and legal consequence. Material support translated into institutional expansion, as churches acquired property, patronage networks, and administrative capacity. These benefits were not merely symbolic gestures of favor; they embedded Christian leadership within the economic and legal structures of the empire. The church’s rise was accelerated by imperial investment, reshaping the balance of influence within urban society.

This patronage reshaped the rhetoric of Christian leadership. Eusebius of Caesarea famously portrayed Constantine as divinely appointed, a ruler chosen by God to guide the empire into truth. Such language reflected more than devotional gratitude. It articulated a theological framework in which imperial power was interpreted as instrument of divine providence. By casting Constantine as God’s chosen agent, Christian leaders sacralized the alliance between throne and church. The emperor’s victories and policies were woven into a narrative of cosmic purpose.

The benefits of imperial backing were concrete and far-reaching. Legal protection ended vulnerability to confiscation and imprisonment, allowing Christian communities to organize openly and expand without fear of sudden repression. Public building projects provided physical spaces that enhanced Christian visibility within urban landscapes, symbolizing permanence and legitimacy. Access to imperial authority enabled bishops to influence legislation affecting marriage law, charitable distributions, clerical exemptions, and ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The church gained leverage in disputes not only against internal theological rivals but also against competing religious traditions. Patronage altered the balance of power across the empire’s religious environment. Within a generation, Christianity moved from precarious minority status to privileged institutional partner, its administrative reach amplified by state endorsement.

Christian leadership embraced Constantine not merely because of personal faith but because the alliance enabled institutional consolidation. Imperial patronage strengthened episcopal authority, expanded material resources, and embedded the church within the machinery of governance. The sacralization of Constantine in Christian discourse reflected recognition of what the partnership achieved. Faith and power converged, each reinforcing the other. In the emerging Christian empire, holiness and imperial utility became increasingly intertwined.

Faith Subordinated to Statecraft

Constantine’s involvement in Christian affairs did not signal the subordination of imperial authority to ecclesiastical control. Instead, it marked the integration of Christian structures into imperial governance under clear executive direction. The emperor intervened directly in theological disputes not as a theologian seeking doctrinal precision, but as a ruler concerned with unity across a vast and politically fragile empire. The Arian controversy demonstrated how theological disagreement could fracture communities from Alexandria to Asia Minor, creating rival episcopal networks that threatened cohesion. Constantine’s correspondence consistently emphasized concord, describing doctrinal conflict as corrosive to civic harmony. His priority was not metaphysical nuance but imperial stability. Religious division was treated as a destabilizing force comparable to political rebellion. The emperor’s concern lay in preserving order, and Christian unity became a strategic objective within that broader agenda.

This pattern extended beyond Nicaea. Constantine intervened in disputes among North African Christians during the Donatist controversy, summoning councils and issuing decisions intended to enforce reconciliation. The Donatist schism centered on questions of clerical legitimacy and sacramental validity, yet for the emperor it represented a breakdown of communal unity within a region critical to imperial administration. By convening synods at Rome and Arles and later confirming judgments against Donatist leaders, Constantine reinforced the expectation that religious conflict required state-managed resolution. His involvement illustrates the emerging model of emperor as arbiter of ecclesiastical division. Religious disagreement was reframed as an administrative problem, and the mechanisms of governance were applied to enforce theological settlement. In this configuration, unity within the church served as an extension of unity within the empire.

The emperor’s authority to convene councils and endorse theological formulas did not arise from clerical office but from sovereign power. Bishops retained doctrinal expertise, yet their deliberations increasingly operated within a framework shaped by imperial expectation. Theological orthodoxy became intertwined with imperial endorsement. This entanglement altered the nature of Christian leadership. Bishops gained influence through proximity to power, but they also navigated constraints imposed by imperial oversight. The relationship between throne and altar became symbiotic yet asymmetrical.

Faith functioned as a stabilizing instrument within the broader architecture of rule. Constantine’s patronage expanded Christianity’s reach, but his interventions demonstrated that the church was expected to contribute to political order. Religious identity could legitimize authority, unify constituencies, and provide moral language for governance. When disputes threatened fragmentation, the emperor stepped in as guarantor of harmony. In this sense, Christianity under Constantine did not displace statecraft; it was absorbed into it, subordinated to the imperatives of imperial stability.

Christianity as Imperial Technology

Constantine’s reign marked a structural shift in the relationship between religious identity and imperial administration. Christianity did not merely receive toleration or even favor; it became embedded within the operating logic of governance. The church possessed features that rendered it uniquely adaptable to imperial purposes. It maintained hierarchical leadership through bishops, fostered communication across provincial boundaries, and articulated a moral language that could universalize imperial authority. These characteristics aligned closely with the needs of a ruler seeking cohesion across a vast and culturally diverse empire.

The episcopal network in particular offered advantages that traditional cults did not. Bishops presided over urban congregations that were already accustomed to coordinated decision-making and doctrinal clarification. Synods functioned as deliberative assemblies capable of producing standardized formulations. This capacity for consensus-building mirrored imperial administrative structures. When Constantine convened councils or issued letters addressing ecclesiastical conflict, he was engaging an institution already organized for transregional coordination. Christianity’s internal coherence provided a ready-made infrastructure through which imperial influence could circulate.

The moral and theological vocabulary of Christianity also offered tools for legitimizing centralized authority. Christian discourse emphasized divine providence, moral order, and obedience within a cosmic hierarchy that located earthly authority beneath divine sovereignty. These themes could be harmonized with imperial ideology, reframing the emperor not merely as political ruler but as agent within a divinely ordered cosmos. By presenting himself as chosen or favored by the Christian God, Constantine reinterpreted sovereignty within a monotheistic framework that transcended local cult loyalties and provincial identities. Unlike traditional Roman religion, which accommodated plurality and localized patronage, Christianity articulated universal claims about truth and salvation that could unify diverse populations under a shared theological narrative. This universality provided ideological depth to imperial claims of unity. The emperor’s role could be framed not merely as protector of Rome, but as guardian of a moral and cosmic order that extended beyond geography. In this synthesis, imperial authority gained theological elevation without surrendering executive control.

Material investment reinforced this ideological alignment. Imperial sponsorship of basilicas, clerical privileges, and church property expansion tied Christian prosperity to imperial favor. Economic dependence fostered institutional partnership. Clergy who benefited from tax exemptions and state support had incentives to defend imperial stability. The church’s increasing involvement in arbitration and social welfare further integrated it into civic life. Christianity did not replace imperial administration, but it supplemented it with moral authority and community structure.

The technological dimension of this alliance lies in its functional adaptability and symbolic power. Christianity provided a unifying narrative capable of absorbing regional diversity into a single framework of belief and moral obligation. It offered language through which suffering, war, and political transition could be interpreted as components of divine purpose rather than mere historical contingency. For an empire emerging from decades of civil conflict and fragmentation, such interpretive coherence held stabilizing potential. The emperor could present himself not simply as victor in civil war, but as instrument of providence guiding the empire toward divinely sanctioned order. Religious meaning amplified political consolidation by translating power into purpose. In this sense, Christianity functioned as imperial technology not through coercion alone, but through narrative integration, moral legitimation, and institutional coordination that extended imperial reach into the realm of conscience and communal identity.

Christianity as imperial technology does not imply insincerity in Constantine’s belief, nor does it deny genuine spiritual conviction among Christian leaders. It highlights instead the structural utility of the alliance. The church’s hierarchy, moral vocabulary, and geographic reach made it an effective partner in governance. In adopting Christianity, Constantine did not abandon Roman traditions of sacral authority; he reconfigured them within a new theological idiom. The fusion of cross and crown produced a durable model in which faith functioned not only as devotion, but as instrument of imperial cohesion.

Comparative Political Theology: Strategic Sanctification

The elevation of Constantine within Christian discourse reflects a recurring pattern in political theology: religious communities sanctifying rulers whose support advances institutional security. Eusebius’s portrayal of Constantine as divinely chosen did not arise in a vacuum of pure devotional enthusiasm or detached theological speculation. It developed within a concrete historical moment in which imperial patronage delivered legal protections, material resources, and unprecedented opportunities for ecclesiastical expansion. Theological language provided interpretive coherence for a political alliance that reshaped Christianity’s position within Roman society. By casting Constantine as God’s instrument, Christian leaders framed imperial favor as evidence of divine providence at work in history. Sanctification functioned not only as spiritual affirmation, but as institutional stabilization. Sacred rhetoric translated political transformation into theological inevitability, embedding the emperor’s authority within the unfolding narrative of salvation.

This pattern does not imply cynicism or disbelief among religious actors. Rather, it reveals how belief and institutional interest often converge. When a ruler provides legal recognition, economic advantage, and administrative partnership, religious leaders may interpret that alignment as providential design. The sacred vocabulary of “being chosen” and divine mission becomes a mechanism for integrating executive authority into a broader theological narrative. In Constantine’s case, the emperor’s selective Christianity did not disqualify him from being hailed as God’s instrument. His usefulness to the church became evidence of divine purpose.

Strategic sanctification becomes most visible when personal piety diverges from idealized moral expectation. Constantine’s delayed baptism and continued engagement in imperial violence did not prevent Christian leaders from framing him as chosen by God. What mattered was the structural outcome of the alliance. Imperial support secured property, expanded ecclesiastical authority, and elevated bishops within civic life. The sanctification of the ruler translated political advantage into sacred meaning. In doing so, it normalized the fusion of throne and altar as mutually reinforcing spheres.

Comparative political theology highlights a durable dynamic: religious movements may anoint rulers not primarily for moral exemplarity, but for the opportunities such rulers provide. Sanctification stabilizes power while power strengthens the religious institution, creating a feedback loop in which institutional gain reinforces theological endorsement. Constantine’s reign offers an early and influential case of this convergence, demonstrating how sacred narrative can absorb political pragmatism without abandoning claims of divine guidance. The sacral language surrounding his authority illustrates how religious endorsement can function as strategic instrument, embedding political partnership within the framework of divine narrative and presenting institutional advantage as providential fulfillment.

Modern Parallel: Evangelical Endorsement and Instrumental Alliance

The overwhelming support of President Donald Trump among large segments of white evangelicals during his first term and continuing into his second term beginning in 2025 reflects a contemporary form of strategic religious alignment. Trump has not consistently embodied the personal moral expectations historically emphasized within evangelical discourse. His rhetoric, public conduct, and religious literacy have often stood in tension with traditional evangelical ideals of humility, fidelity, and devotional discipline. Yet this divergence has not prevented many evangelical leaders from framing him as providentially chosen or divinely used. As in earlier moments of political theology, usefulness has frequently outweighed conformity to spiritual exemplarity.

The logic of this alignment rests primarily in policy outcomes. Judicial appointments reshaping the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court, have been central to evangelical political priorities. Legislation and executive actions concerning abortion, religious liberty claims, and educational policy have reinforced perceptions that Trump advances a long-standing cultural agenda. In this framing, political effectiveness becomes theological evidence. The ruler is defended not because he reflects moral perfection, but because he delivers structural victories. Sacred language stabilizes the alliance by translating political success into signs of divine favor.

Religious rhetoric surrounding Trump has often invoked biblical archetypes of flawed leaders used by God to accomplish providential ends. Such comparisons enable reconciliation between doctrinal standards and political loyalty. By emphasizing divine sovereignty over imperfect instruments, evangelical leaders reframe moral dissonance as providential design. This strategy mirrors earlier patterns in which sanctification absorbs political pragmatism. The alliance is sustained through interpretive narratives that elevate institutional gain above personal virtue.

This modern parallel underscores the durability of strategic sanctification within political theology. Just as Christian leaders in the fourth century interpreted Constantine’s patronage as divine intervention despite selective religious commitment, contemporary evangelical endorsement has frequently emphasized the instrumental value of executive power. The fusion of religious identity with political authority promises legal protection, cultural influence, and policy advancement. In both contexts, faith does not disappear, but it is integrated into statecraft in ways that privilege institutional security. Sanctification becomes less a measure of holiness than a language of political consolidation.

Conclusion: When Empire Adopts Faith

Constantine did not simply convert to Christianity; he incorporated it into the architecture of imperial governance. His reign illustrates how religious transformation at the highest level of power can operate as strategic realignment rather than pure devotional rupture. By legalizing Christianity, patronizing its leadership, and intervening in its disputes, Constantine embedded the church within the machinery of the state. The alliance did not erase Roman traditions of sacral authority but reinterpreted them within a Christian idiom. The emperor remained sovereign, and faith became one of the instruments through which sovereignty was articulated.

For Christian leadership, the partnership yielded unprecedented security and influence. Legal protection, economic patronage, and expanded jurisdiction elevated bishops from vulnerable minority leaders to institutional partners of empire. The theological sanctification of Constantine reflected recognition of what the alliance enabled. Sacred narrative absorbed political pragmatism and framed it as providential design. In doing so, Christianity moved from marginal sect to imperial collaborator, reshaping its identity in the process.

The long-term consequences of this fusion extended far beyond Constantine’s lifetime. The model of emperor as guardian of orthodoxy and arbiter of doctrinal unity became embedded in Christian political thought. Subsequent centuries would witness recurring negotiations between ecclesiastical authority and executive power, each drawing upon precedents established in the fourth century. The sacralization of imperial rule under Constantine did not mark the end of conflict between church and state, but it established a durable template for entanglement.

When empire adopts faith, faith is transformed even as empire is legitimated. Religious identity acquires administrative function, and political authority acquires theological language. The alliance between cross and crown demonstrates that sanctification can operate as strategy as well as devotion. Constantine’s reign stands as an early and influential example of how belief systems can be integrated into statecraft, not merely embraced personally but deployed institutionally. In that integration lies the enduring lesson of political theology: sacred narratives can stabilize power, and power can reshape the sacred.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. Religions of Rome, 2 Vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Bleckmann, Bruno. “Constantine, Rome, and the Christians.” In Contested Monarchy: Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD, Johannes Wienand, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, AD 200–1000. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

- Cannon, Katie Geneva. “Christian Imperialism and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 24:1 (2008), 127-134.

- Chow, Christopher J. “The Edict of Milan and the Early Roots of Christianity in the Roman Empire.” Young Historians Conference 23 (2017).

- Conroy-Krutz, Emily. Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

- Drake, H. A. Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Du Mez, Kristin Kobes. Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. New York: Liveright, 2020.

- Eusebius of Caesarea. Life of Constantine. Translated by Averil Cameron and Stuart G. Hall. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

- Fea, John. Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018.

- Fox, Robin Lane. Pagans and Christians. New York: Knopf, 1986.

- Jones, Robert P. The End of White Christian America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors. Translated by J. L. Creed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

- MacMullen, Ramsay. Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100–400). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

- Markus, R. A. The End of Ancient Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.20.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.