Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Note: All pictures from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Years of Adventure, 1874-1914

West Branch, Iowa

Herbert Clark Hoover was born on August 10, 1874, in the town of West Branch, Iowa, where he lived the first nine years of his life. His Quaker father, Jessie Clark Hoover, a blacksmith and farm equipment salesman, died of a Heart attack when Herbert was six years old. Three years later, Herbert’s mother, Huldah Minthorn Hoover died from pneumonia. Herber, his older brother Theodore, and younger sister Mary were orphaned. Herbert went to live with his uncle, Dr. John Minthorn, in Newberg, Oregon.

Oregon

In Oregon, Hoover attended Friends Pacific Academy and excelled in mathematics. He was determined to go to a new college, in Palo Alto, California—Leland Stanford University. He studied hard and barely passed the university’s entrance exam. While at Stanford he majored in geology and participated in many extracurricular activities. To help with college expenses he started a laundry service, did typing chores for his professor, and worked summers making geological maps.

Mining Career

After he graduated, he worked at a gold mine in California, pushing an ore cart. After working in an office in San Francisco, Hoover was hired by an English corporation to manage mines in Australia, where he found gold. Based on this success, the company sent Hoover to China to manage their operations. For the next decade he worked in similar jobs all over the world and became known as “the Chief.”

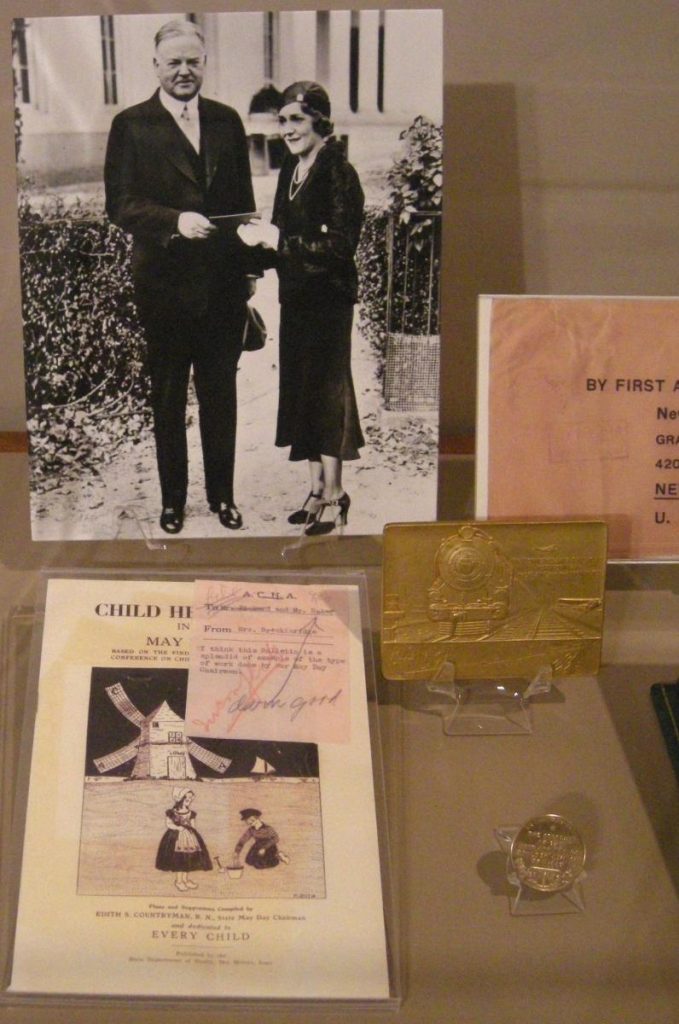

Family and China

Lou Henry Hoover, his wife, traveled with him everywhere he went. They met in college, where she was the first woman to major in geology at Stanford. He proposed to her by cable from Australia. She accepted and they married on February 10, 1899, before boarding a ship and moving to China.

While in China, Herbert Hoover worked to enhance the profitability of their mines. Lou traveled with her husband, studying Chinese culture and language. The Hoovers were based in Tientsin when the Boxer Rebellion broke out in June 1900. Despite being under siege for one month (and being shelled by mortars), Lou described this as “the most exciting time of her life.” After the siege was broken, the Hoovers moved to London.

Herbert and Lou had two children, Herbert Jr. (1903) and Allan (1907). In 1907 Hoover and his family were based in London, traveling around the world to almost 40 nations, working as a mining engineer and consultant. In 1908 Hoover opened his own consulting business, and by 1914 he was financially secure.

Years of Compassion, 1914-1923

Public Service

Herbert Hoover was raised a Quaker, although as an adult he rarely attended Meetings. He held fast the Quaker tenets: the power of the individual, the importance of freedom, and the value of charity. Hoover’s beliefs were also shaped by his training as an engineer—that scientific expertise properly employed leads to human progress. He strongly believed in public service.

By 1914 Hoover yearned for more than wealth. When the U.S. Consul General in London asked him to organize the evacuation of 120,000 Americans who were stranded in Europe, Hoover was provided with an opportunity for public service.

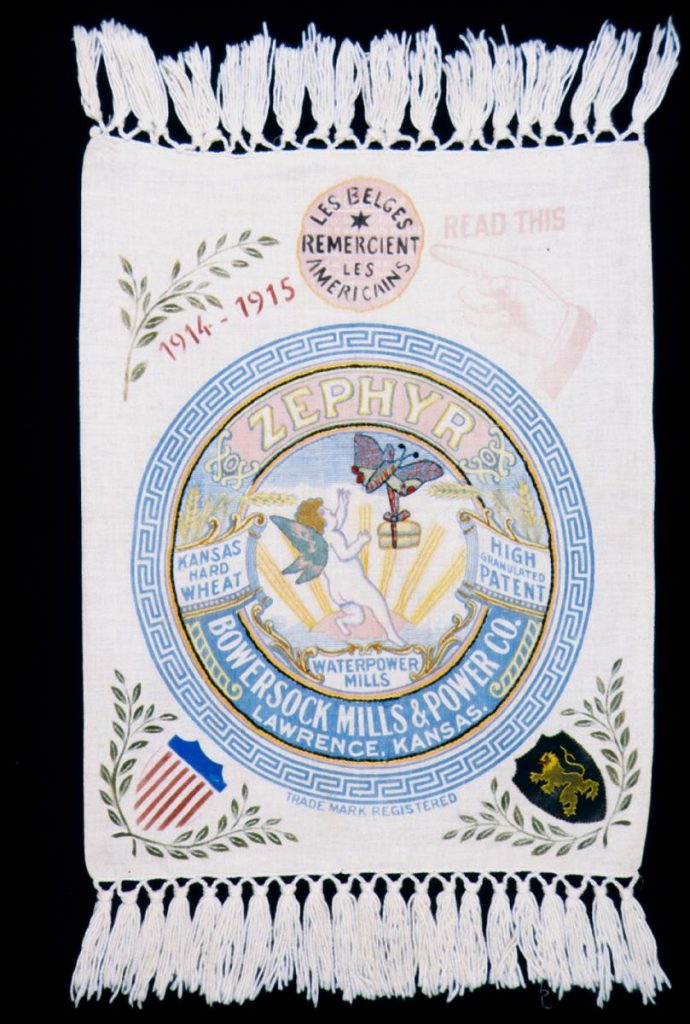

Commission for Relief in Belgium

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Germany invaded the neutral country of Belgium, hoping to quickly overrun France. By October 1914, food supplies in Belgium were nearly exhausted. The American ambassadors to Belgium and Great Britain persuaded the British to allow the importation of food under American supervision on the condition that none of it would go to Germany or the German army in Belgium. They promised the Germans that the distribution would not be used to aid the Allies or to spy on the German army. Herbert Hoover was asked to lead the project, which came to be called the Commission for Relief in Belgium, (CRB).

In order to distribute food equitably and to prevent the growth of the black market, the CRB collected and rationed all locally grown food along with the imported supplies. By mid-November, food supplies reached all parts of occupied Belgium, and there was no catastrophic famine from that point forward, though rations for all were strictly limited for the duration. Herbert Hoover gained worldwide fame as the “Great Humanitarian” for creating an unprecedented organization that fed 10 million civilians for five years in the midst of a war zone.

U.S. Food Administration

In 1917, after the United States entered the war, Hoover was named to head the U.S. Food Administration. Hoover was the right man for the job, which guided the effort to conserve resources and supplies and to feed America’s European allies. Hoover became a household name—“to Hooverize” meant to economize on food. Americans began observing “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays” and planting War Gardens. Within a year, the United States had doubled its food shipments to Europe. After the Armistice was signed in November 1918, President Wilson appointed Hoover to head the European Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Hoover was able to channel 34 million tons of American food, clothing and supplies to war-torn Europe.

Years of Enterprise, 1921-1928

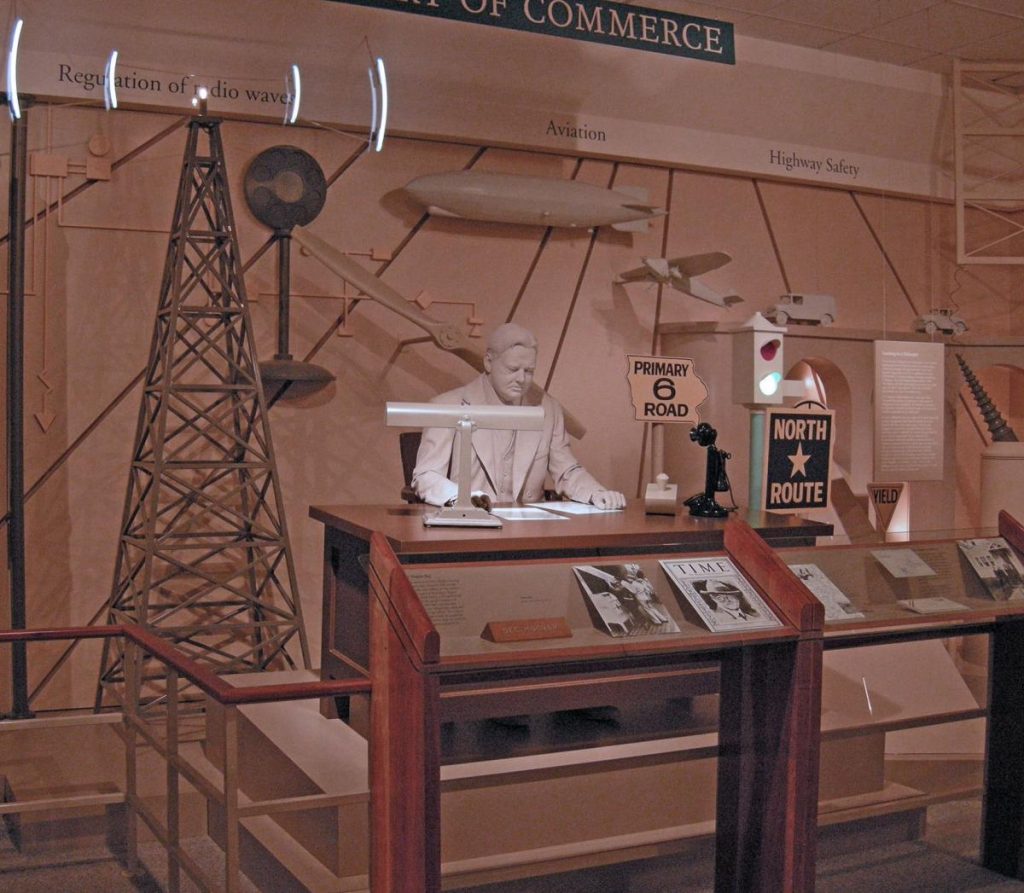

Secretary of Commerce

When Warren Harding was elected President in 1920, he appointed Herbert Hoover Secretary of Commerce. The Commerce Department had traditionally been a sleepy backwater, primarily responsible for lighthouses and fisheries. Hoover made the Commerce Department a powerful organization, with a mission to help business and industry become more profitable and efficient, both for the owners and the workers.

Hoover encouraged research into measures to counteract harmful business cycles. He supported government regulation of new industries like aviation and radio. He standardized tools, hardware, building materials, and auto parts to various industries. Finally, he pursued international trade opportunities for American business. To effect these reforms, Hoover strengthened existing Commerce Department agencies or established new ones. He also formed commissions that brought together government officials, experts, and leaders of the relevant sectors to expand the economy.

Through the initiatives he supported, Hoover hoped to create an economy that would smooth the business cycle, eliminating damaging ebbs and flows and generating higher growth. He believed that eradicating waste and improving efficiency would achieve these results. He also believed that the American economy would be healthier if business leaders worked together, with government officials and experts from the social sciences, in a form of private-sector economic planning. This stance led him to support trade associations—industry-wide cooperative groups wherein information on prices, markets, and products could be exchanged among competitors—which Hoover saw as a middle way between competition and monopoly. He insisted, though, that participation in these associations remain voluntary and that the government merely promote, rather than require, their establishment.

Colorado River

For many years, residents of the American Southwest had dreamed of taming the unpredictable Colorado River. By the early 1920s, it was clear that without an agreement on the distribution of water, the project could not proceed. A commission was formed in 1922, chaired by Secretary of Commerce Hoover. The resulting Colorado River Compact, signed on November 24, 1922, split the river basin into upper and lower halves, with the states in each region deciding how the water would be divided. This agreement, known as the Hoover Compromise, paved the way for construction of what would become the Hoover Dam. President Calvin Coolidge signed the Boulder Canyon Project into law in 1928. On September 17, 1930, Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur marked the beginning of construction by naming the dam in Hoover’s honor.

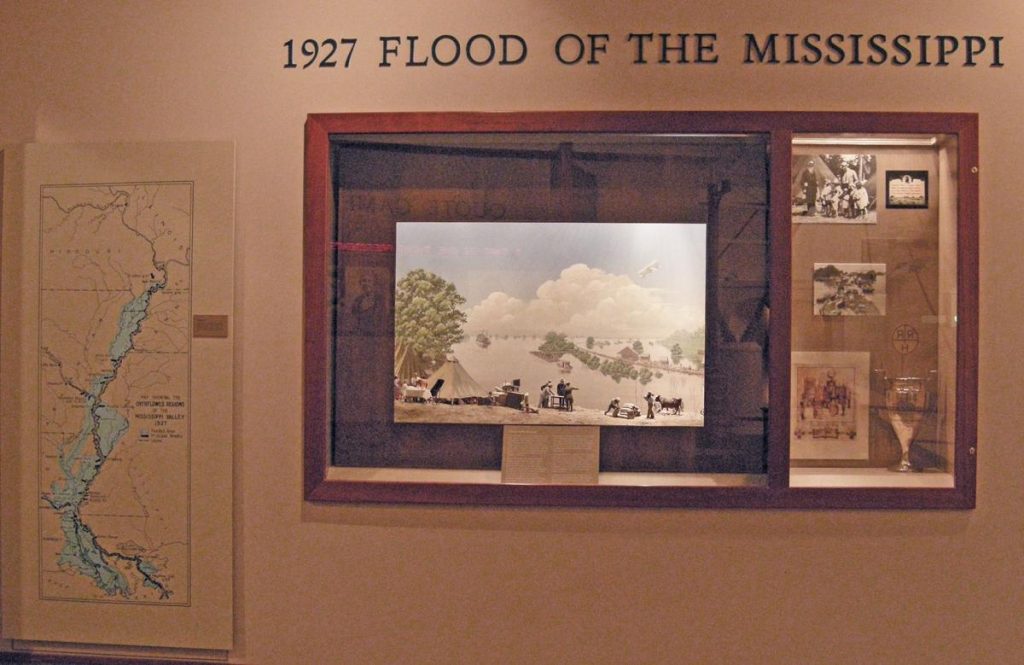

Mississippi Flood

Hoover’s positions and thinking placed him solidly in the progressive camp of the Republican Party. His reputation with the American people reached its peak in 1927, when he took charge of relief efforts following floods of the Mississippi River. President Coolidge sent him to mobilize state and local authorities, militia, Army engineers, Coast Guard, weather bureaus, and the Red Cross. His leadership during the flood brought Herbert Hoover to the front page of papers everywhere. When Coolidge announced in 1927 that he would not seek reelection, Hoover became the leading candidate for the Republican Presidential nomination.

Years of Leadership, 1928-1933

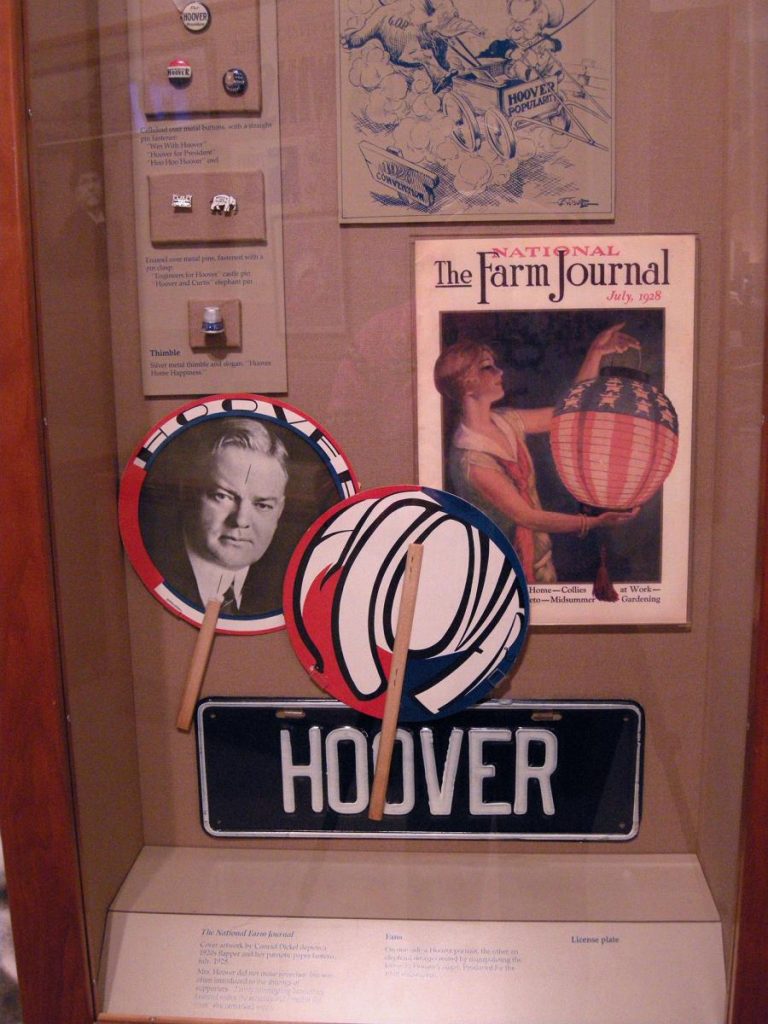

Candidate and Election

Herbert Hoover, at the age of 53, was on the verge of winning the Republican Party’s nomination for President when the convention began in June 1928. He had won primaries in several states with the support of women, progressives, internationalists, the new business elite, and corporate interests. The Old Guard Republicans, suspicious of Hoover’s activist approach to government, had little choice but to accept the popular Commerce Secretary as their candidate. Kansas Senator Charles Curtis was named to be his Vice Presidential running mate.

In November, Hoover won 58 percent of the popular vote and 444 electoral votes to Al Smith’s 87. In December 1928, Hoover said, “My friends have made the American people think me a sort of superman. They expect the impossible of me and should there arise in the land conditions with which the political machinery is unable to cope I will be the one to suffer.”

Hoover’s Accomplishments

On March 4, 1929, Herbert Hoover became the 31st President of the United States. Brimming with constructive ideas to improve the federal government, the new President set to work with his characteristic energy. He announced an expansion of civil service protection throughout the federal government, ordered a review of private oil leases on public land in order to root out abuses that had caused scandals during the Harding Administration, and directed federal law enforcement officials to focus their energies on gangster-ridden Chicago.

Within days, President Hoover called a special session of Congress to address the farm crisis that had festered for over a decade—low commodity prices and overproduction were driving many farmers off their land. Hoover proposed a Federal Farm Board to finance agricultural cooperatives that would give farmers more bargaining power for better prices, and would help their members avoid overproduction. Within three months, Congress passed legislation that put Hoover’s plan into action.

Hoover pressed ahead with plans for dams in the Tennessee Valley and California, and a massive program of prison reform. Hoover proposed and implemented the Veterans Administration to centralize all veterans’ services into one agency, and established the Anti-Trust Division of the Justice Department to prosecute unfair trade practices. Hoover also reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and advocated federal loans for urban slum clearance. He proposed a federal Department of Education, as well as $50-a-month pensions for Americans over 65—both ideas fell by the wayside after Wall Street crashed.

In November 1930, Hoover presided over the White House Conference on Child Health and Protection, which led to child welfare reforms at the state and local level. Another White House conference the following year focused on home building and home ownership.

On the international scene, Hoover worked to halt the arms race through the 1930 London Naval Conference and the 1932 World Disarmament Conference in Geneva. He initiated a “Good Neighbor Policy” to improve relations with Latin America, and began removing U.S. forces that had been sent to “keep the peace” in the region. He supported the establishment of a World Court and worked to make the U.S. a member. In January 1932, the United States refused to recognize Japan’s invasion of Manchuria; through the Hoover-Stimson Doctrine, the administration hoped to mobilize world opinion to restore Chinese sovereignty.

Against All Odds

The whirlwind successes of Hoover’s first months in office didn’t last. A stock market crash in October 1929 signaled the beginning of the relentless economic collapse that became known as the Great Depression. Hoover’s honeymoon with Congress ended even before the stock market crash. After creating the Federal Farm Board, Congress turned to revising the tariff—a major Republican campaign promise. Hoover lost control of the legislative process as members of Congress piled up protections for favored industries in their districts. In June 1930, Hoover reluctantly signed the resulting Smoot-Hawley tariff bill, even as economists warned that it could worsen the economic situation. After the 1930 mid-term election, Republican control of the House slipped away and Hoover faced an uphill battle for almost any legislation he proposed.

Severe droughts in the Midwest in 1930 and 1931 decimated the already weak agriculture sector, leaving even more farm families destitute, and virtually bankrupting Hoover’s Farm Board. Bank failures in Europe in 1931 threatened to upend the rickety international financial system and further damaged America’s sagging economy. Hoover staved off disaster by calling for a one-year moratorium on international debt payments, giving countries time to restructure their crushing debts—many of which were owed to U.S. banks.

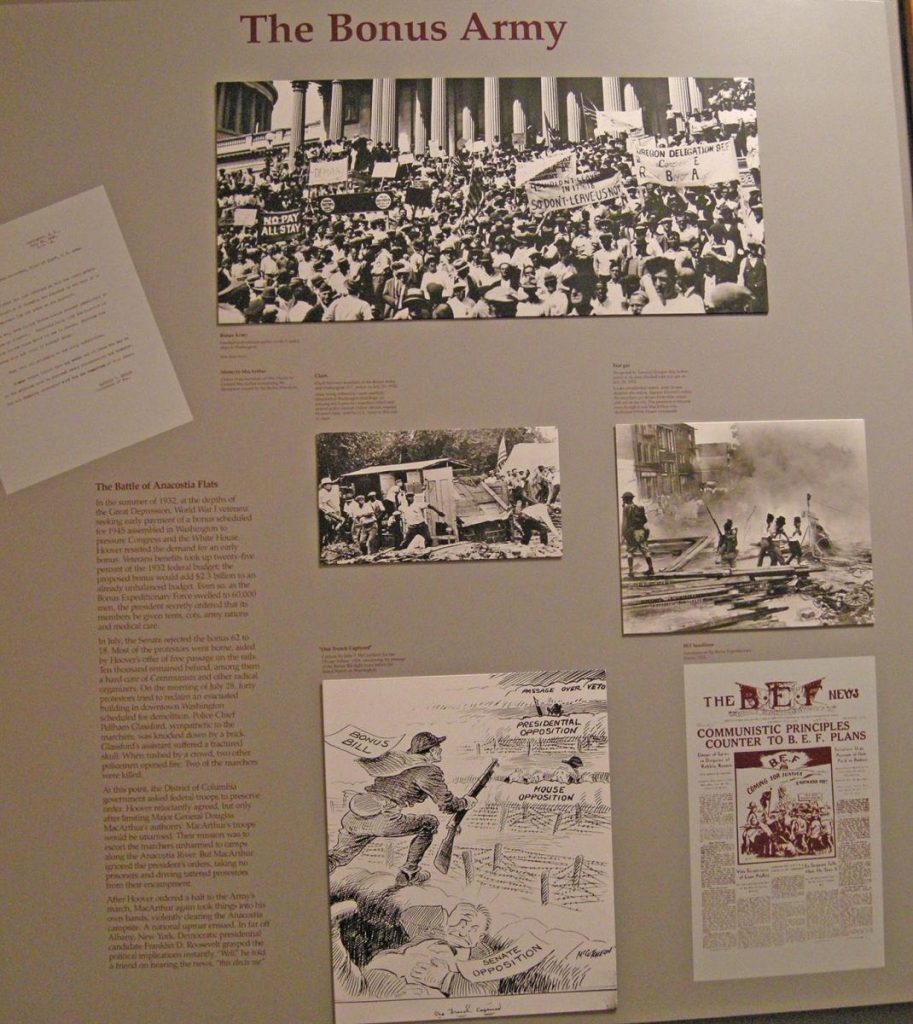

“We are opposed by six million unemployed, 10,000 bonus marchers, and 10 cent corn,” said Herbert Hoover as he prepared to run for reelection in 1932. Unemployment, bank failures and the farm crises had left Hoover’s reputation as an economic miracle-worker in tatters. The Bonus March made the Great Humanitarian look inhumane. In the summer of 1932, World War I veterans seeking early payment of a bonus scheduled for 1945 marched on Washington. In July the Senate rejected the bonus and most of the Bonus Army returned to their homes. Ten thousand remained behind. On the morning of July 28, a scuffle with the police turned into a riot, and the city government asked President Hoover to send troops. Hoover ordered Gen. Douglas MacArthur to quell the riot using as little force as possible. MacArthur, fearing revolution, ignored the President’s orders, advanced on the protesters with tanks and tear gas, and burned the Bonus Army’s encampment to the ground. A national uproar ensued. In New York, Democratic Presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt grasped the political implications instantly. On hearing the news, he told a friend, “This elects me.”

Unwilling to concede race to Roosevelt, and hoping that enough Americans still had faith in his leadership, Hoover took to the campaign trail beginning with an October 4 speech on farm policy. He campaigned relentlessly over the next 5 weeks, but lost the election in a landslide bigger than the one that had swept him into office four years earlier.

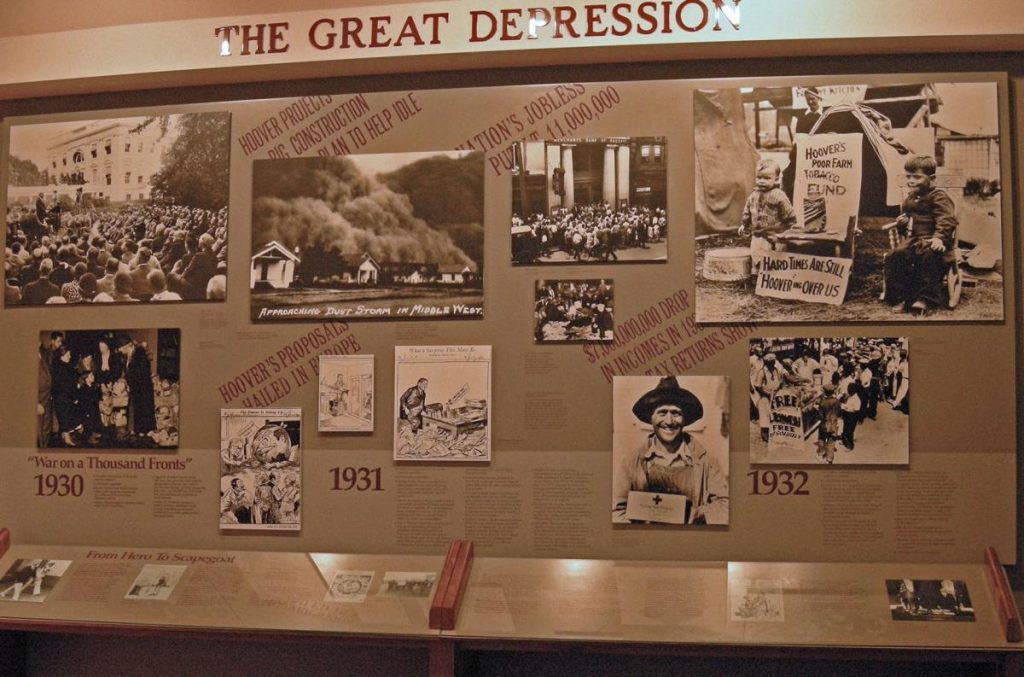

The Great Depression

1929

The 1920s were a period of optimism and prosperity – for some Americans. When Herbert Hoover became President in 1929, the stock market was climbing to unprecedented levels, and some investors were taking advantage of low interest rates to buy stocks on credit, pushing prices even higher. In October, 1929, the bubble burst, and in less than a week, the market dropped by almost half of its recent record highs. Billions of dollars were lost, and thousands of investors were ruined.

After the stock market crash, President Hoover sought to prevent panic from spreading throughout the economy. In November, he summoned business leaders to the White House and secured promises from them to maintain wages. According to Hoover’s economic theory, financial losses should affect profits, not employment, thus maintaining consumer spending and shortening the downturn. Hoover received commitments from private industry to spend $1.8 billion for new construction and repairs to be started in 1930, to stimulate employment.

The President ordered federal departments to speed up their construction projects and asked all governors to expand public works projects in their states. He asked Congress for a $160 million tax cut while doubling spending for public buildings, dams, highways, and harbors.

1930

Praise for the President’s intervention was widespread; the New York Times commented, “No one in his place could have done more. Very few of his predecessors could have done as much.” Together, government and business spent more in the first half of 1930 than in the entire previous year. Still consumers cut back their spending, which forced many businesses and manufacturers to reduce their output and lay off their workers.

In October 1930, with unemployment rising, Hoover created the President’s Emergency Committee for Employment (PECE) to coordinate state and local relief programs, and to develop methods for increasing employment in the private sector. But with no direct control of funding for relief or jobs, PECE had only limited success.

As the Depression worsened, Hoover requested that the Federal Reserve increase credit, and he persuaded Congress to transfer agricultural surpluses from the Federal Farm Board to the Red Cross for distribution to relief agencies. Hoover asked Congress for even more spending on public works, and he continued to encourage states and private businesses to generate new jobs.

1931

Economic conditions improved in early 1931 until a series of bank collapses in Europe sent new shockwaves through the American economy, leading to additional lay-offs. In August 1931, PECE was reorganized as the President’s Organization on Unemployment Relief (POUR). POUR expanded on PECE’s work but also implemented a national fund drive for unemployment relief. The national fund drive raised millions of dollars but proved to be woefully inadequate as unemployment soared to record levels.

Hoover was criticized for almost every program he proposed. His public works projects, designed to create jobs, were characterized as wasteful government spending. His efforts to promote local relief programs, rather than asking Congress to create nationwide relief programs, were viewed as callous disregard for the unemployed.

1932

On January 22, 1932, Hoover established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to make emergency loans to businesses in danger of default. At first the RFC lent money only to banks, railroads, and certain agricultural organizations, but the scope of its operations was later expanded, and it proved to be an effective tool for stabilizing business and industry. In July 1932, Hoover signed into law the Emergency Relief Construction Act, which allowed the RFC to lend $300 million to the states for relief programs and $1.5 billion for public works projects. Hoover also persuaded Congress to establish Federal Home Loan Banks to help protect people from losing their homes.

By the summer of 1932, the Great Depression had begun to show signs of improvement, but many people in the United States still blamed President Hoover. With the Presidential election approaching, the Democratic candidate, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, exuded hope and optimism, and promised the people a “New Deal.” Hoover, defending his record, came across as pessimistic and defeated. In November, Roosevelt won in a landslide.

1933

Four long months intervened between the election and Roosevelt’s inauguration. Economic signs that had looked so promising in the summer of 1932 trended downward, unemployment went up, and banks failed at an alarming rate. As weak banks closed their doors, nervous depositors began withdrawing cash from even the soundest banks, but Congress refused to enact Hoover’s plans to stem the panic. When Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, the banking system was near total collapse, and unemployment had reached 25%. Within days, Congress passed and FDR signed into law the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which stemmed the panic and restored confidence in the financial system – and was almost identical to legislation Hoover had proposed weeks before. Despite all the efforts of Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” the Depression persisted seven more years, until World War II stimulated the economy with increased demand for commodities and war materials.

Lou Henry Hoover

Early Life

Lou Henry Hoover, humanitarian, Girl Scout leader, and First Lady of the United States, was born in Waterloo, Iowa, in 1874. She spent the first decade of her life in Iowa, where she developed a deep appreciation for outdoor life and camping. She moved with her family to California in 1885, where she continued her exploration of nature. Lou Henry earned a teaching degree in 1893 but decided to continue her education, pursuing a geology degree from Stanford. While a student at Stanford, she met Herbert Hoover. They married on February 10, 1899, and departed for China the next day.

World Traveler

For the next 14 years, the Hoovers traveled the world, developing mines in Burma, Russia, Australia, and South Africa. During this time, Lou gave birth to two sons, Herbert Jr. in 1903 and Allan in 1907. In their spare time, Lou and Herbert translated De Re Metallica, a medieval encyclopedia on mining and metallurgy, from Latin into English. They were both awarded the Gold Medal for lifetime achievement by the International Mining and Metallurgical Society for this work.

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Lou’s life in London changed dramatically. She helped thousands of Americans stranded in Europe by the war return to the United States. Lou provided lodging, clothing and guidance in the first chaotic month of the war. After Herbert Hoover became chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, Lou organized a California branch and raised funds for one of the first shipments of food. When America entered the war in 1917, Lou encouraged American women to conserve food for the war effort.

Girl Scouts

Late in the war, Lou met Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts. For the rest of her life, Lou devoted hours and energy to the organization. She served as a troop leader in Washington, DC, and in Palo Alto and twice served as president of the Girl Scouts of America, once in the 1920s and again after leaving the White House in 1933. During her second term, Girl Scout leadership approved a national plan to bake and sell cookies as a fundraiser for scouting.

First Lady

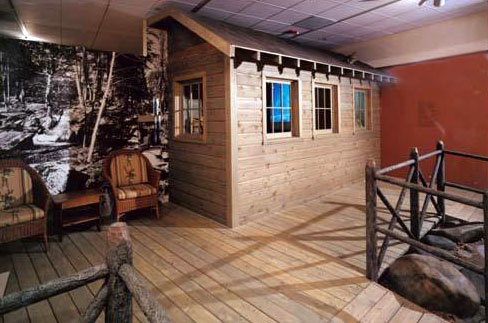

As First Lady from March 4, 1929, to March 4, 1933, Lou Hoover was frequently in the public eye. Although she did not give many speeches, she did make the first radio broadcast given by a First Lady. She also caused a teapot tempest when she invited Jessie DePriest, wife of African-American congressman Oscar DePriest, to the White House for tea. Some in the press corps criticized Lou for this social transgression, and the incident made her wary of the press. Lou initiated an effort to document the provenance of White House furnishings and rooms, resulting in a book-length study that formed the basis for later histories of the White House. She was instrumental in developing and designing the cabins for the President’s Camp on the Rapidan, a getaway retreat purchased by the Hoovers and used throughout their White House years.

Camp Rapidan

Every president needs a place to escape from the cares and burdens of office. For the Hoovers that place was Camp Rapidan, a rustic fishing camp located one hundred miles from Washington in Virginia’s scenic Blue Ridge Mountain range and built with $120,000 of the president’s own money. Those who visited the camp saw a very different man from the harried executive whose days were blighted by economic crisis. At Rapidan, Hoover could discard the formal gear of Washington for white flannels and a Panama hat. He pitched horseshoes with Charles Lindbergh and, sitting on a log with a British Prime Minister, made plans for a world disarmament conference to be held in London in 1930.

When the Hoovers discovered that local children had no school they donated funds to build one and to hire a teacher. Most days the First Lady rode horseback, occasionally stopping in nearby Madison to patronize local rugmakers or furniture craftsman. In the evening Lou invited guests to join her as the moon rose over Fork Mountain. It was a welcome alternative to the tumult of politics and dinners for visiting royalty.

Later Years

After Hoover lost his reelection bid in 1932, the Hoovers were happy to return to private life. They returned to Palo Alto to live in the house designed by Lou Henry Hoover, hoping to have a quiet retirement surrounded by family, friends, and the Stanford campus. In the late 1930s, the Hoovers began to divide their time between Palo Alto and New York City. Lou Hoover died in New York City in early January 1944 at the age of 69.

Years of Struggle and Acclaim

Life after the White House

Rejected by his countrymen, Hoover departed Washington in March 1933. His once bright reputation was in shambles, his career in public service apparently at an end. Yet he refused to fade away.

The Boys Club of America

In October 1936 the former President found a new cause, one that would engage him for the rest of his life. For Hoover this was the latest chapter in a story of an Iowa orphan who had gone on to feed children throughout Europe.

A Comfortable Monastery

Beginning in December 1940, Hoover lived primarily in New York City. Home was Suite 31-A of the Waldorf Towers, a Park Avenue landmark. Here Hoover conducted a very productive post-Presidency. At the age of 86, he traveled 14,000 miles, delivered 20 speeches, and accepted many awards and citations.

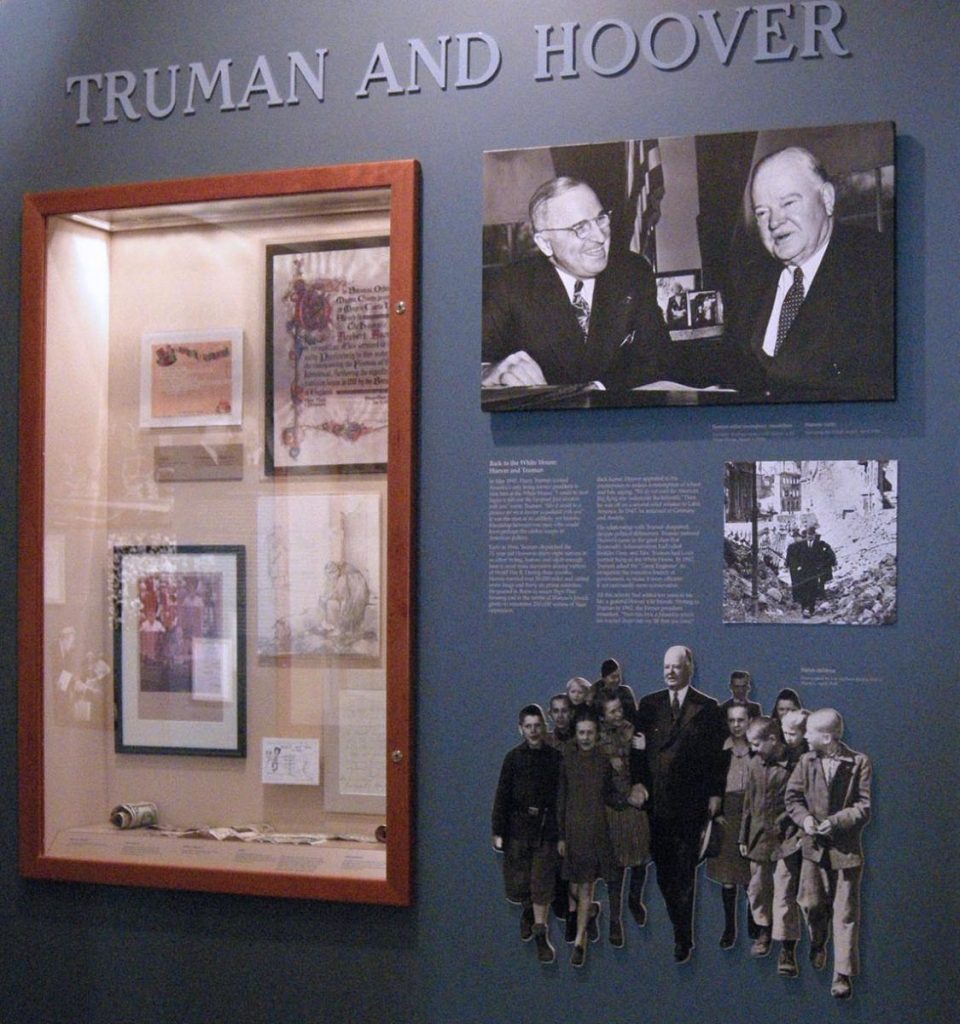

Back to the White House

In 1945 President Harry Truman invited Hoover to the White House. “I would be most happy to talk over the European food situation with you,” wrote Truman. “Also it would be a pleasure for me to become acquainted with you.” It was the start of an unlikely, yet historic, friendship between the two men.

Early in 1946 Truman dispatched the 71-year-old Hoover to 38 nations in an effort to avert mass starvation among victims of World War II. During three months, Hoover traveled more than 50,000 miles. He went on a second relief mission to Latin America, and in 1947 he returned to Germany and Austria.

His relationship with Truman deepened, despite political differences. Truman restored Hoover’s name to the great dam that had been called Boulder Dam.

Writing to Truman in 1962, the former President remarked, “Yours has been friendship which has reached deeper into my life than you know.”

The Hoover Commissions

In 1947 Hoover undertook a massive reorganization of the executive branch of the federal government.

Do more with less: that was the theme of the commission’s reports, each written by Hoover. Not all his ideas were approved, but Harry Truman supported enough to see that more than 70 percent of Hoover’s recommendations were enacted into law.

In 1953 a Second Hoover Commission returned to the task of pruning big government. As late as 1961, John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert MacNamara, was thanking Hoover for ideas that could save billions in Pentagon spending.

Counselor to the Republic

The Angler

Herbert Hoover’s lifelong passion for fishing is well known. For no other President has a biographer written a 350-page book subtitled, The Fishing President, as Hal Elliott Wert has done for Hoover. In this book, Wert describes Hoover’s fishing exploits and expeditions from age 8 to age 88. Hoover never tired of the piscine pursuit, fishing for trout in freshwater streams, bonefish in saltwater flats, and any fish that would take the bait in deepwater oceans. Hoover’s passion for fishing led him to wax lyrical in writing—not common for Hoover. His addresses to the Izaak Walton League in the 1920s led to Hoover being named honorary chairman of the league from 1926 to 1932. Hoover compiled his thoughts on fishing in Fishing For Fun—And to Wash Your Soul. He opened this book with: “Fishing is a chance to wash one’s soul with pure air, with the rush of the brook, or with the shimmer of the sun on the blue water. . . . It is discipline in the equality of man—for all men are equal before fish.

Death and Burial

In October 1964, just months after his 90th birthday, Hoover sent Harry Truman a get-well telegram after his friend injured himself in a bathtub fall. Soon after, Hoover suffered massive hemorrhaging in the stomach and intestine and passed away a few days later on October 20, 1964.

Following ceremonies in New York and Washington, the President was flown to Iowa. A crowd of tens of thousands gathered in West Branch. Dr. Elton Trueblood, a Quaker theologian and family friend, declared that Herbert Hoover would be remembered for as long as the American Dream was cherished. “He has worked hard; he has been very brave; he has endured,” concluded Trueblood.

Today America’s 31st President is buried within sight of the cottage where his life began. In a final demonstration of Quaker simplicity, there is no Presidential seal, no inscription of any kind on the stone—just the name Herbert Hoover and the dates 1874–1964.

Originally published by the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives and Records Administration, under United States government public domain.