Elders keep the past as storytellers. They transmit a culture’s identity to the next generation.

By Dr. Christopher M. Bellitto

Professor of History

Kean University

We like to say we honor our elders, but do we really?

Do they become expendable because they can no longer go to work? What does it mean to say that someone is no longer productive or doesn’t provide results? Is a human being’s worth to be measured only by the dollars he or she produces?

Time for a history lesson.

Elders keep the past as storytellers. They transmit a culture’s identity to the next generation. In plays and myths ranging from those of ancient Athens to Shakespeare’s nurse in England’s “Romeo and Juliet,” ancient sages bring messages from the gods, offer good advice (which the proud young usually ignore) and act as oracles and interpreters of dreams. We think of wizards both medieval and modern, from the legendary Merlin to the fictional Dumbledore and Gandalf, from the historical Chinese philosopher Confucius to American authors Mark Twain and Maya Angelou. We turn to them not for instant analysis but for long-term experience and perspective born from traveling rocky roads.

It’s a nice image to think that ancient cultures revered their elders, but did they? In researching the cultural context of the Bible for my new book, “Ageless Wisdom: Lifetime Lessons from the Bible,” I was surprised to learn that the ancient Greeks, for instance, had to be goaded into caring for the elderly. Adult children had to be legally bound to care for their parents; candidates for public office were checked to see that they had, indeed, fulfilled their obligations toward their mother and father. One of the Athenian laws of Solon from the sixth-century BCE stipulated that if an Athenian did not care for his parents, he would lose his rights as a citizen – a fate worse than death for an Athenian.

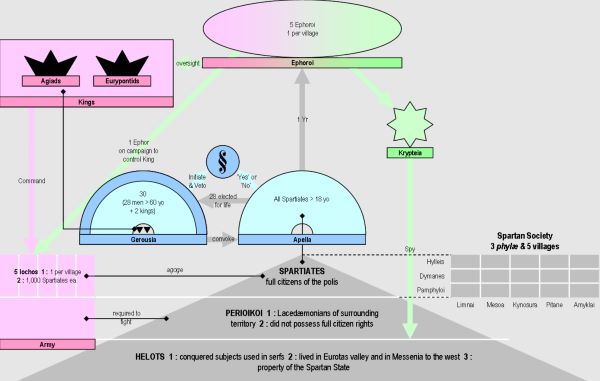

There were exceptions. In ancient Sparta, a powerful governing body was the Gerousia, a word related to the Greek geron, meaning an old man; we get the name for the fields of geriatrics and gerontology from this root.

The Gerousia was a council of elders comprising the two sitting kings and 28 elected men over the age of 60 who served for life. This powerful council controlled Sparta’s legislative agenda, selecting which bills would go to the larger Assembly for votes; even then, its members retained a veto over the Assembly’s actions. The Gerousia also constituted the criminal court for the worst crimes, such as treason and homicide, where the penalty was the loss of citizenship, exile or death. Within the Assembly itself, those over 50 years of age were permitted to speak first – certainly a platform for their running for a spot in the Gerousia when they turned 60.

To illustrate the point, in his “De Senectute” (45/44 BCE), on old age, Cicero tells a terrific story of an old man entering an Athenian theater. He looked for a seat, but not one Athenian stood. When he reached the section where the visiting Spartans (normally the Athenians’ archenemies) were sitting, every single Spartan stood up to offer his place. The entire audience applauded. “These Athenians know what politeness is,” one of the Spartans observed, we imagine with a sneer, “but they won’t practice it.”

Spartan respect stands out among the customary indifference, even disdain, for the elderly that we find among the rest of the Greeks. Male gods are sometimes old and bearded to demonstrate their power or wisdom, but their bodies represent a modern Mr. Olympia more than a real-life old man who might tend sheep on the slopes of Mount Olympus.

Geras, the Greek god of old age, is depicted as a hobbled, thin, defenseless, vulnerable and wrinkled fellow whom we would see as worthy of pity more than worship or fear. There are hardly any depictions of older goddesses at all. One especially stands out by its negativity. In Hesiod’s “Theogony,” we read about the birth of the gods. There, Night is named as the mother of Old Age, who is described as sad and accursed.

The implications for support of our rapidly aging population are staggering, but are they being examined? Can the past help us see a right and better way to honor our elders? Yes, but only if we view past, present and future with open eyes.

Will we act like the Athenians or the Spartans?

Originally published by NorthJersey.com, 03.20.2017, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.