Introduction

What is the difference between a civil right and a human right? Simply put, human rights are rights one acquires by being alive. Civil rights are rights that one obtains by being a legal member of a certain political state. There are obviously several liberties that overlap between these two categories, but the breakdown of rights between human and civil is roughly as follows:

Human rights include:

- the right to life

- the right to education

- protection from torture

- freedom of expression

- the right to a free trial

Civil rights within the United States include:

- protection from discrimination

- the right to free speech

- the right to due process

- the right to equal protection

- the right against self-incrimination

It is important to note that civil rights will change based on where a person claims citizenship because civil rights are, in essence, an agreement between the citizen and the nation or state that the citizen lives within. From an international perspective, international organizations and courts are not as likely to intervene and take action to enforce a nation’s violation of its own civil rights, but are more likely to respond to human rights violations. While human rights should be universal in all countries, civil rights will vary greatly from one nation to the next. No nation may rightfully deprive a person of a human right, but different nations can grant or deny different civil rights. Thus, civil rights struggles tend to occur at local or national levels and not at the international level. At the international stage, we focus on the violation of human rights.

This guide will focus on the civil rights that various groups have fought for within the United States. While some of these rights, like the right to education, certainly overlap with human rights, we treat them as civil rights in most academic conversations. Typically, the reason used to justify a right to equal education or another human right is grounded in a civil right of due process or equal protection.

Civil Rights for People of Color

Overview

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration of Independence

The relationship between African Americans and the United States of America was forged in slavery. The South built its economy on the backs of slaves. After a Civil War that threatened to tear the nation apart, slavery ended but the injustices that blacks faced did not. Rather than fold them into society and offer them opportunities for advancement, blacks were instead treated like little more than slaves. Policies were implemented to keep blacks working the same fields they had worked as slaves. Those who did move away were subject to living in certain, poorer neighborhoods due to redlining. Blacks were segregated in schools, restaurants, on transportation, and in other forms of public accommodations. They were discriminated against for employment. And all of this was legal. Not only was it legal; it was considered normal – exactly as it should be – by most of the population of our nation throughout the post-Civil War era and well into the 20th century. It was not until after WWII that things began to change. And when that change came, it came with a struggle. For every deserved right that blacks have gained, they have had to fight. That fight continues into our own time – it will continue as long as the inequality between the races exists.

The Jim Crow Period (1870s-1950s)

After the Civil War, there was a period from about 1865 to 1877 where federal laws offered observable protection of civil rights for former slaves and free blacks. However, starting in the 1870s, as the Southern economy continued its decline, Democrats took over power in Southern legislatures and used intimidation tactics to suppress black voters. Tactics included violence against blacks and those tactics continued well into the 1900s. Lynchings were a common form of terrorism practiced against blacks to intimidate them. It is important to remember that the Democrats and Republicans of the late 1800s were very different parties from their current iterations. Republicans in the time of the Civil War and directly after were literally the party of Lincoln and anathema to the South. As white, Southern Democrats took over legislatures in the former Confederate states, they began passing more restrictive voter registration and electoral laws, as well as passing legislation to segregate blacks and whites.

It wasn’t enough just to separate out blacks – segregation was never about “separate but equal.” While the Supreme Court naively speculated in Plessy v. Ferguson that somehow mankind wouldn’t show its worst nature and that segregation could occur without one side being significantly disadvantaged despite all evidence to the contrary, we can look back in hindsight and see that the Court was either foolishly optimistic or suffering from the same racism that gripped the other arms of the government at the time. In practice, the services and facilities for blacks were consistently inferior, underfunded, and more inconvenient as compared to those offered to whites – or the services and facilities did not exist at all for blacks. And while segregation was literal law in the South, it was also practiced in the northern United States via housing patterns enforced by private covenants, bank lending practices, and job discrimination, including discriminatory labor union practices. This kind of de facto segregation has lasted well into our own time.

The era of Jim Crow laws saw a dramatic reduction in the number of blacks registered to vote within the South. This time period brought about the Great Migration of blacks to northern and western cities like New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan experienced a resurgence and spread all over the country, finding a significant popularity that has lingered to this day in the Midwest. It was claimed at the height of the second incarnation of the KKK that its membership exceeded 4 million people nationwide. The Klan didn’t shy away from using burning crosses and other intimidation tools to strike fear into their opponents, who included not just blacks, but also Catholics, Jews, and anyone who wasn’t a white Protestant.

This time period was not without its triumphs for blacks, even if they came at a cost or if they were smaller than one would have preferred. The NAACP was founded in 1909, in response to the continued practice of lynching and race riots in Springfield, Ill. From the 1920s through the 1930s in Harlem, New York, a cultural, social, and artistic movement took place that was later coined the Harlem Renaissance. Musicians like Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, writers such as Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, it-girls like Josephine Baker, and philosophers like W.E.B. Du Bois all had a hand in the Harlem Renaissance and American culture as a whole is richer and better for it.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873) – this series of three cases, which were consolidated into one issue, offered the first opinion from the Supreme Court on the 14th Amendment. The court chose to interpret the rights protected by the 14th Amendment as very narrow and this precedent would be followed for many years to come.

- Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) – in this set of five cases that were consolidated into one issue, a majority of the court held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional against the lone famous dissent of Justice Harlan. The majority argued that Congress lacked authority to regulate private affairs under the 14th Amendment and that the 13th Amendment “merely abolishe[d] slavery”. Segregation in public accommodations would not be declared illegal after these cases until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) – this is the case which gave us the phrase “separate but equal” and upheld state racial segregation laws for public facilities. Justice Harlan again offered a lone dissent. These laws would remain in play until 1954.

Library Resources:

- Ronald M. Labbé and Jonathan Lurie, The Slaughterhouse Cases: Regulation, Reconstruction, and the Fourteenth Amendment, KF228.S545 L33 2005

- Williamjames Hull Hoffer, ‘Plessy v. Ferguson’: Race and Inequality in Jim Crow America, KF223.P56 H64 2012

- Laurie Collier Hillstrom, Plessy v. Ferguson, KF223.P56 H55 2014

- Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, HV6457 .E635 2015

- African American Newspapers, 1827-1998 – this database provides online access to around 270 U.S. newspapers from more than 35 states. Includes many rare and historically significant 19th century titles.

- Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law – HeinOnline

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Non-Violent Demonstrations

You may shoot me with your words,

Fragment from ‘Still I Rise’ by Maya Angelou

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

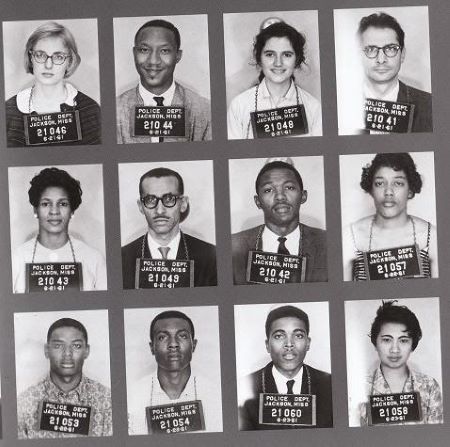

There comes a time when a people will no longer be held down. Historians have speculated as to the confluence of circumstances that led to the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s. Some say it was a response to the similarities between what was happening to blacks in the South and what we had fought against in WWII – how could we allow one and be against the other? Others say the advent of television, and the ability to see people being hosed by police on the nightly news, made it somehow more real than it had previously been. This argument has been brought back out in our own time with the repeated cell phone videos of black men being shot by cops. In truth, all of these factors and more contributed to the climate and ensured that a change was going to occur. Blacks were no longer going to accept separate and unequal. And while many in the South were reluctant to see their way of life change, there were those who were ready to see a change – whether they came in via bus from other parts of the country or sat bravely with friends at the lunch counter, or marched with others and faced arrest – there were people who stood up to authorities and defended what they knew was right.

Lives were lost in the fight for civil rights. Emmett Till was lynched in 1955 while visiting relatives in Mississippi because he reportedly flirted with a white woman – he was 14 years old. His killers walked away, having been acquitted and then admitted in a magazine interview that they killed him. Medgar Evers was shot in his own driveway – it took almost 30 years for a jury to convict his killer. Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Carol Denise McNair (age 11), Carole Robertson (age 14), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14), were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. Four people died while involved in the Selma marches. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Non-violent demonstrations don’t always end in non-violent results. And sometimes the victims of protests have nothing to do with the protesters themselves. Change doesn’t come easily and it doesn’t come without a cost.

As time went on, civil rights groups found themselves splintering into different factions over how to handle the issues they faced. Some wanted to take bolder stances and a more proactive approach. And even when a bolder approach was taken, there were still losses – Malcolm X and Fred Hampton both stand out as significant losses to the cause. Others continued to follow King’s methods even after he was gone. In-fighting within an ideology or political party isn’t a new concept but we can learn from the obstacles that civil rights groups faced in the 1960s.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) – this decision ruled that a criminal prohibition against burning a draft card was not a violation of the First Amendment guarantee of free speech.

- Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence, 468 U.S. 288 (1984) – this case held that the regulations of the National Park Service which prohibited a group from overnight sleeping in conjunction with a demonstration on the National Mall and other federal grounds were not in violation of the First Amendment.

- Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989) – this case invalidated prohibitions on desecrating the American flag enforced in 48 of the 50 states. Burning the flag in this instance was considered protected speech under the First Amendment, as the flag was burned as part of a political protest.

Library Resources:

- Claybourne Carson, et al., eds., The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., E185.97.K5 A2 1992

- Claybourne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s, E185.92 .C37 1995 (Also available online)

- Robert Justin Goldstein, Flag Burning and Free Speech: The Case of Texas v. Johnson, KF224.J64 G65 2000

- Donald P. Krommers et al., American Constitutional Law: Essays, Cases, and Comparative Notes, KF4550 .K65 2010

- Rufus Burrow, Jr., Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Theology of Resistance, available online

- Taylor Branch, The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement, E185.61 .B7913 2013

Desegregation

Desegregation did not happen overnight. In fact, it took years for some states to get on board, and some had to be brought on kicking and screaming. But before the Court ever got involved with school integration, the desegregation wheels were put into motion by another branch of the government – the president himself. In 1948, Harry Truman issued an executive order to integrate the armed forces after WWII. Even though it took three years for the army to fully act on the order, once it did, the military found that the earth still rotated and weapons still worked.

Schools are what we tend to think of when we hear the word segregation. And it was schools that the Court spent a fair amount of time discussing in its opinions on desegregation. But the Court had time to issue opinions on other matters as well. For instance, the Court defended Congress in its ability to draft legislation that would allow blacks to integrate with whites in the area of employment. The Court also supported Congress in preventing racial discrimination in facilities like restaurants.

And the Court even went so far as to integrate love, holding that states could no longer prohibit interracial relationships. The importance of the Supreme Court’s willingness to uphold civil rights for blacks cannot be denied; this is not the same court that decided Plessy v. Ferguson some 70 years before.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Brown v. Bd. of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) – this was the seminal case in which the Court declared that states could no longer maintain or establish laws allowing separate schools for black and white students. This was the beginning of the end of state-sponsored segregation.

- Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964) – this case held that Congress could use its power to force private businesses to abide by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) – in this case, the Court held that Congress acted within its power under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution in forbidding racial discrimination in restaurants as this was a burden to interstate commerce.

- Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) – this landmark case invalidated all laws prohibiting interracial marriage.

Library Resources:

- George W. Noblit, ed., School Desegregation: Oral Histories Toward Understanding the Effects of White Domination, available online

- Richard C. Cortner, Civil Rights and Public Accommodations: The Heart of Atlanta Motel and McClung Cases, KF224.H43 C67 2001

- Kevin Stainback and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, Documenting Desegregation: Racial and Gender Segregation in Private Sector Employment since the Civil Rights Act, HD4903.5.U58 S69 2012

- Peter Wallenstein, Race, Sex, and the Freedom to Marry: Loving v. Virginia, KF224.L68 W35 2014

- Rebeka L. Maples, The Legacy of Desegregation: The Struggle for Equality in Higher Education, LC212.72 .M37 2014

Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is labor law legislationthat outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace and by facilities that served the general public (public accommodations). Initially, the powers given to enforce the act were weak, but they were supplemented in later years. Congress asserted its authority to legislate via several different parts of the Constitution, principally its power to regulate interstate commerce, its duty to guarantee all citizens equal protection of the laws through the 14th Amendment, and its duty to protect voting rights under the 15th Amendment.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 was the culmination of a campaign against housing discrimination and was approved at the urging of President Johnson, one week after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Its primary prohibition makes it unlawful to refuse to sell, rent to, or negotiate with any person because of that person’s inclusion in a protected class. The goal is a unitary housing market in which a person’s background (as opposed to financial resources) does not arbitrarily restrict access. Calls for open housing were issued early in the twentieth century, but it was not until after World War II that concerted efforts to achieve it were undertaken. While the act stopped some of the more egregious instances of housing discrimination, it should be noted that we are far from fair when it comes to housing and one’s ability to obtain it. Race is still an issue and has been despite the efforts made through the acts listed here.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) – in this case, the court upheld affirmative action, allowing that race could be one of several factors to consider in college admission policy. However, the court struck down specific racial quotas as impermissible.

- Texas Dept. of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, Inc., 576 U.S. ___ (2015) – this case held that disparate impact claims were intended to be a part of the Fair Housing Act but that a plaintiff must prove that it is a defendant’s policies that have caused the disparity.

Library Resources:

- Robert D. Loevy, ed., The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law that Ended Racial Segregation, KF4757 .C59 1997

- June Manning Thomas and Marsha Ritzdorf, eds., Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows, HT167 .U7277 1997 (Main Campus)

- Bernard Grofman, ed., Legacies of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, KF4757 .L44 2000

- David C. Carter, The Music has Gone Out of the Movement: Civil Rights and the Johnson Administration, 1965-1968, E185.615 .C3517 2009

1965 Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 offered African Americans a way to get around the barriers at the state and local levels that had prevented them from exercising their 15th Amendment right to vote. After it was signed into law by LBJ, Congress amended it five more times to expand its scope and offer more protections. This law has been called one of the most effective pieces of civil rights legislation ever enacted by the Dept. of Justice. Its gutting by the decision in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013 has led to more restrictive voting laws in at least 7 states.

The sections of the Voting Rights Act affected by Shelby County were 4(b) and 5. Section 4(b) contained a coverage formula designed to encompass jurisdictions that were the most pervasively discriminatory and hold them liable to special provisions within the Voting Rights Act, to ensure that previously-barred minorities within those jurisdictions would be protected and able to practice their right to vote. The coverage formula was always considered controversial because it singled out specific jurisdictions, most of which were in the Deep South. In Shelby County, the Supreme Court declared the coverage formula unconstitutional because the criteria used were outdated and thus violated principles of equal state sovereignty and federalism.The other special provisions that were dependent on the coverage formula, such as the Section 5 pre-clearance requirement, remained valid law, but without a valid coverage formula these provisions became unenforceable. The pre-clearance requirement meant that jurisdictions which fell under 4(b) had to get federal approval to any changes they attempted to make in their election laws. With this requirement gone, states with a history of discriminatory behavior could now make changes without federal approval.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. ___ (2013) – in this case, the Court held that section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was unconstitutional because the formula used to determine coverage was based on data that was 40 years old, making it no longer representative to current needs. This caused a ripple effect among several states, such as Alabama, Arizona, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin, all of whom have passed voter ID laws that removed online voter registration, early voting, same-day registration, and pre-registration for teens about to turn 18. In each case, the laws have become more restrictive.

Library Resources:

- Bruce J. Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism: A Brief Biography with Documents, E847 .S35 2007 (Main Campus)

- Laurie Collier Hillstrom, The Voting Rights Act of 1965, JK1924 .H55 2009

- Charles S. Bullock III, et al., The Rise and Fall of the Voting Rights Act, KF4891 .B85 2016

The War on Drugs and Mass Incarceration

No discussion of civil rights for blacks can be complete without addressing the issue of mass incarceration and that issue, while complicated, and having roots as far back as the end of the Civil War, was exacerbated by the policies put in place by President Reagan and Congress when they declared a war on drugs. Those policies were maintained by Bush and even intensified by the crime bill passed in 1994 by President Clinton. It was only in George W. Bush’s second term that the sentencing disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine was finally addressed by the Supreme Court. Even still, a disparity in sentencing between the two drugs remains, despite the fact that they have been determined to be almost the same substance.

Misguided drug laws and draconian sentencing requirements, especially pertaining to crack cocaine, have produced profoundly unequal outcomes for communities of color. The results have decimated minority families – black men in particular have been victims of the wars on drugs and on crime. Although rates of drug use and selling are comparable across racial and ethnic lines, blacks and Latinos are far more likely to be criminalized for drug law violations than whites. Although minorities use and sell drugs at a similar rate as whites, the proportion of those incarcerated in state prisons for drug offenses who are black or latino is 57 percent.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005) – this case held that the sentencing guidelines, which to this point had been mandatory, were instead advisory and that courts needed to look to the history and characteristics of defendants when deciding sentence lengths.

- Kimbrough v. United States, 552 U.S. 85 (2007) – this case took the holding in Booker and applied it specifically to the guidelines as they pertained to crack cocaine versus powder cocaine. There was a huge discrepancy in the sentencing of crack cocaine dealers/users versus dealers/users of powder cocaine (the 100-to-1 ratio) and this case confirmed that judges were free to use their discretion when sentencing defendants in crack cocaine cases.

Library Resources:

- Jonathan Birnbaum and Clarence Taylor, Civil Rights since 1787: A Reader on the Black Struggle, E184.6 .C595 2000

- David Garland, ed., Mass Imprisonment: Social Causes and Consequences, HV8705 .M37 2001

- Linda F. Williams, The Constraint of Race: Legacies of White Skin Privilege in America, E185.61 .W7365 2003

- Doris Marie Provine, Unequal Under Law: Race in the War on Drugs, KF4755 .P76 2007

- Henry Louis Gates Jr., Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History, 1513-2008, E185 .G27 2011

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, HV9950 .A437 2012

- Elizabeth Kai Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, HV9950 .H56 2016

The Obama Administration

On November 4, 2008, Barack Hussein Obama II became the 44th President of the United States of America. He also became the first black president. He has gone on to serve two terms. Under his watch, the country began to recover from the worst recession since the Great Depression, two women were appointed to the Supreme Court, gay marriage was declared by that same Court to be a fundamental right, Osama bin Laden was killed in a surgical raid conducted by U.S. Navy SEALs, the Affordable Care Act was passed, a nuclear deal was struck with Iran, and relations with Cuba moved forward.

On the other hand, racial tensions within the U.S. have mounted as more and more blacks, particularly black men or youth, are shot and killed by law enforcement. With cell phone videos capturing some of the incidents and social media being used to broadcast protestors’ side of the story, many have been shocked into action, much like those a generation before who were shocked by the images they saw of marchers in Selma being hosed by police. Movements like Black Lives Matter (BLM) have arisen on the one side to protect the civil rights of blacks and those movements are countered by activists who argue that BLM is a terrorist movement or that police are the ones threatened.

The fact that the economy remains stagnant in certain areas of the country does not help ease the tensions between races or between citizens and immigrants, legal or otherwise. In states like Ohio and Michigan, where manufacturing was once robust but has now withered, people are angry and want change that can’t be easily provided by any politician or businessman.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) – this case reaffirmed that strict scrutiny must be applied to determine the constitutionality of a university’s affirmative action admission policy.

Library Resources:

- Timothy Davis et al., eds., A Reader on Race, Civil Rights, and American Law: A Multiracial Approach, KF4755 .R43 2001

- F. Michael Higginbotham, Race Law: Cases, Commentary, and Questions, KF4755.A7 H54 2005

- George Packer, The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America, E839 .P28 2013

- Ian Haney-López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class, E185.615 .H278 2014

- Kenneth Osgood and Derrick E. White, eds., Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency from Nixon to Obama, E185.615 .W547 2014

- Black Studies Center – this database combines videos, transcripts, a periodical index, historical black newspapers, and a black literature index into one location for research and teaching.

- Oxford African American Studies Center – this is a comprehensive collection of scholarly articles, primary sources, maps, charts, tables, biographies, and encyclopedias on the African and African American experiences.

- Civil Rights Texts & Treatises

- Civil Rights Law

- Making of Modern Law – ACLU Papers, 1912-1990

Additional Resources:

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Case for Reparations, THE ATLANTIC, June 2014, available here

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, My President was Black: A history of the first African American White House — and of what came next, THE ATLANTIC, December 2016, available here

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

- PBS, Eyes on the Prize – this is a documentary but the website has some useful information as well

- Ava DuVernay, director, 13th, available on Netflix – this documentary offers an in-depth look at the U.S. prison system and reveals the nation’s history of racial inequality

- The Drug Policy Alliance

- Families Against Mandatory Minimums

Women’s Civil Rights

Overview

You’ve come a long way, baby….or have you?

Women have gained the right to vote and decisions like Roe v. Wade allowed them to make their own reproductive decisions. But since that decision almost 44 years ago, women’s rights to decide for themselves when it comes to reproductive matters have been chipped away over time. Women are now at a critical juncture. Funding for Planned Parenthood is threatened, as are the rights established by Roe v. Wade and its ilk.

Furthermore, women’s rights activists must come together and be inclusive of all women rather than expecting women of color to bend to a white version of feminism. This holds true for accepting transgendered and lesbian or bisexual activists as well. Women’s rights activists need to work to see each other’s viewpoints and gain an understanding of what each perspective can bring to the table.

Women have made strides in the workplace but the wage gap still exists and there are areas that women have yet to conquer. Perhaps someday a woman will be elected President of the United States. In the meantime, women should seek to be more equally represented in the government, both on the national and state/local levels. As of 2015, 104 women hold seats in the U.S. Congress; out of 535 members, this is approximately 19%. Clearly, there is more work to be done.

The past year has been difficult as stories of convicted sexual assailants given lenient sentences flooded social media. It would be easy to feel as though women are being devalued or even actively fought against. But there is hope. Women are not alone and women can overcome the hurdles they face today. It will take unity and courage.

Women and the Vote

Prior to the passing of the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, many states within the U.S. did not allow women to vote. The national movement to gain a vote for women began in 1848 in New York, with abolitionists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. That it took 70 years for the suffragist movement to come to fruition via the 19th amendment was indicative of several issues; one, that it was very hard to get an amendment passed; two, that it was very difficult to grant rights to women as a group that had been traditionally subservient; three, that factors like the civil war and ensuring that blacks received the right to vote afterward were priorities that took precedent and slowed the process.

The suffragist movement was not without its own issues – some suffragettes were unwilling to entertain the notion of allowing black women the right to vote. There was resentment in the suffrage movement over the 15th Amendment and the fact that black men were given the right to vote before women. Suffragettes like Francis E. Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, went so far as to court Southern white women at the expense of blacks by portraying blacks as alcoholic fiends ready to assault women. Despite being friendly with many blacks, Willard was not afraid to slander them in order to gain favor with those who would help her get the vote for women. This drove a considerable wedge between her and suffragists like Ida B. Wells. Other suffragettes felt violence was the best way to get their point across, which led to some group members being arrested and serving jail time.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Lesser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922) – this case was brought to challenge the validity of the ratification of the 19th amendment. The court unanimously held that the ratification was valid.

Library Resources:

- Jean H. Baker, Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists, JK1896 .B35 2005

- Richard Chused & Wendy Williams, Gendered Law in American History, KF478 .C495 2016

- Gender and Legal History in America Papers – the library has a collection of papers from a seminar taught by Richard Chused and Wendy Williams here at Georgetown Law.

Women’s Reproductive Rights

Women like Margaret Sanger and Mary Ware Dennett were early proponents of women’s right to contraception and sex education. Though they were met with great resistance, their efforts allowed for later generations to at least discuss birth control as an option. It was not until the 1960s, however, and the introduction of the birth control pill, that women could impede pregnancy for the first time by their own choice. However, several major religious institutions opposed contraceptives and many states banned the sale of artificial contraceptives, even to married couples. It would take Supreme Court decisions to make the pill accessible to women – single and married.

Abortion was another hurdle to be overcome. While Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, and held that a woman’s constitutional rights were violated by states that banned abortion, the decades since that decision have seen restrictions and limitations placed upon it, making abortions more difficult to obtain. At the same time, access to birth control is also not always readily accessible and many would like to see organizations like Planned Parenthood, which strive to offer affordable reproductive services to women, defunded.

Currently, states like Ohio are focused on abortion bans that will limit when women can seek out abortions. This indicates a trend towards greater restrictions on women’s reproductive rights in the future.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) – this case held that married couples had a constitutional “right to privacy” regarding decisions about childbearing and that a state ban on the sale of contraception was thus unconstitutional.

- Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) – this case extended the right to contraception to unmarried individuals.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) – the case that held that state bans on abortions were unconstitutional.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) – this case laid out the “undue burden test,” under which state regulations can survive constitutional review so long as they do not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.”

- Stenberg v. Carhart (Carhart I), 530 U.S. 914 (2000) – this case struck down a Nebraska “partial-birth abortion” law because it did not include a health exception and it posed an undue burden on women who needed second-trimester abortions as it banned the most common second-trimester method.

- Gonzales v. Carhart and Gonzales v. Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (Carhart II), 550 U.S. 124 (2007) – this case upheld a federal ban – the “Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003.”

Library Resources:

- Judith A. Baer, ed., Historical and Multicultural Encyclopedia of Women’s Reproductive Rights in the United States, HQ766.5.U5 H57 2002

- NARAL Foundation, Who Decides? The Status of Women’s Reproductive Rights in the United States, KF3771.Z95 W46 2005 (Also available online)

- Mary Ziegler, After Roe: The Lost History of the Abortion Debate, HQ767.5.U5 Z54 2015

The Equal Rights Amendment

The concept behind the Equal Rights Amendment was simple enough: Congress would have the power to enforce legal equality between men and women via an amendment to the constitution. From 1923 until 1970, the amendment was introduced for consideration during every congressional session but almost never made it to a vote. Despite this seeming inertia, there was a change afoot during the latter part of this period. The activism of the 1960s that gave way to second-wave feminism and saw the formation of organizations like NOW in 1966 provided for publicity of the Equal Rights Amendment. It passed the House of Representatives and Senate in 1972 and then went to the states for ratification. Many states ratified it quickly but there was also a lot of debate between those who supported the amendment and those opposed to it. As the deadline for ratification loomed in 1979, 30 of the required 38 states had ratified the amendment. Congress extended the ratification deadline to 1982 but no additional states ratified the amendment.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971) – this was the first sex discrimination case under Title VII. It held that employers could not refuse to hire women with pre-school aged children while hiring men with children of the same age.

- Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971) – this case struck down an Illinois law that stated “males must be preferred to females” when dealing with appointing estate administrators. This specification was found to be undeniable gender bias and the Court held that the law’s dissimilar treatment of men and women was unconstitutional.

- Geduldig v. Aiello, 417 U.S. 484 (1974) – this case held that the denial of insurance benefits for work loss resulting from a normal pregnancy did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. The California insurance program at issue did not exclude workers from eligibility based on sex but excluded pregnancy from a list of compensable disabilities.

- United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996) – This case ruled against the Virginia Military Institute’s male-only admissions policy. VMI was the last public institution with a gender bias and this case ended that issue.

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ___ (2014) – this case allowed closely held for-profit corporations to be exempt from a law its owners religiously object to if there was a less restrictive means of furthering the law’s interest, according to the provisions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). In this particular case, the corporation did not have to follow the contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act due to the court’s decision.

Library Resources:

- Anne K. Bingaman, A Commentary on the Effect of the Equal Rights Amendment on State Laws and Institutions: Prepared for the California Commission on the Status of Women’s Equal Rights Amendment Project, KF4758 .B5 1975

Feminism and Intersectionality

The issues that divided early suffragettes still plague women today. For all the forward progress that has been made, women’s rights activists have also taken steps backwards. Feminism, as a movement, has not done a good job at being inclusive of minorities. Women of color have been left on the peripheries while feminism has largely catered solely to white viewpoints.

Feminism is spoken of in waves – first wave feminism encompasses the suffragettes of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century – the women who fought for the right to vote. Second wave feminism generally encapsulates the period from the 1960s to the 1990s. This period runs concurrent with anti-war and civil rights movements and the dominant issues for feminists in this time period revolved around sexuality and reproductive rights. Third wave feminism is generally seen as starting in the mid-1990s and is sometimes referred to as girlie-feminism or “grrrl” feminism. Its adherents often confounded followers of second wave feminism because many third wavers rejected the notion that lip-stick, high-heels, and cleavage proudly exposed by low cut necklines identified with male oppression. This was in keeping with the third wave’s celebration of ambiguity and refusal to think in terms of “us versus them.” Most third-wavers refused to identify as “feminists” and rejected the word because they found it limiting and exclusionary.

The fourth wave of feminism is still crystallizing. Feminism is now back in the realm of public discourse. Issues that were central to the earliest phases of the women’s movement are receiving national and international attention by mainstream press and politicians: problems like sexual abuse, rape, violence against women, unequal pay, slut-shaming, the pressure to conform to an unrealistic body-type, and the fact that gains in female representation in politics and business are minimal. At the same time, reproductive rights that had been won by second wavers are now under attack. It is no longer considered “extreme” to talk about societal abuse of women, rape on college campus, unfair pay and work conditions, discrimination against LGBTQ friends and colleagues, and the fact that the US has one of the worst records for legally-mandated parental leave and maternity benefits in the world.

With the rise of fourth wave feminism, the concepts of privilege and intersectionality have gained widespread traction amongst younger feminists. Intersectionality is a term that was first introduced in 1989 by critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw. It is a framework that must be applied to all situations women face, a framework that recognizes all the aspects of identity that enrich women’s lives and experiences and that compound and complicate the various oppressions and marginalizations women face. It means that women cannot separate out numerous injustices because women experience them intersectionally.

Intersectionality helps us to understand that while all women are subject to the wage gap, some women are affected even more harshly due to their race. Another instance where intersectionality applies is cases of LGBTQ murders – people of color and transgendered people are more likely to be victims than cisgender people. These are just two examples of why intersectionality matters. To truly bring about change that is meaningful for all, everyone’s voice needs to be at the table.

Library Resources:

- Cynthia Grant Bowman et al., Feminist Jurisprudence: Cases and Materials, KE478.A4 B43 2011

- Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs et al., eds., Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia, LB2332.3 .P74 2012

- Women and the Law Collection – HeinOnline

- Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000

- Making of Modern Law – ACLU Papers, 1912-1990

Additional Resources:

- 10 Landmark Court Cases in Women’s Rights

- Timeline of Major Supreme Court Decisions On Women’s Rights

- Documents from the Women’s Liberation Movement

- Black Women and the Suffrage Movement: 1848-1923

- The Root: How Racism Tainted Women’s Suffrage

LGBTQ+ Civil Rights

Overview

Discrimination continues to exist against minorities of all kinds, including towards members of the LGBTQ community. Historically, anyone who strayed from the traditional gender roles assigned at birth were often characterized as mentally defective or psychopaths. Treatments for individuals exhibiting these traits varied from sterilization and castration to lobotomies and conversion therapy. In addition to the risk of being subjected to these traumatic therapies, societal expectations led many to adjust their behaviors and appearance in order to pass as straight. These pressures could lead to suicide, drug abuse, and homelessness.

Significant progress has made in civil rights that have dramatically improved the legal protections available to this community, but challenges remain. This section of the guide outlines both the historical developments as well as related resources.

Library Resources:

- The right side of history: 100 years of revolutionary LGBTQI activism, HQ76.8.U5 R54 2015

- Law and the gay rights story: the long search for equal justice in a divided democracy, eBook 2014 (also available in print)

- Queer (in)justice: the criminalization of LGBT people in the United States, KF4754.5 .M64 2011

- Smash the church, smash the state!: the early years of gay liberation, HQ76.8.U5 2009

- Dishonorable passions: sodomy laws in America,1861-2003, KF9328.S6 E84 2008

- Come out fighting: a century of essential writing on gay and lesbian liberation, HQ76.8.U5 C66 2001

- Gay and lesbian rights: a reference handbook, HQ76.3U5 N48 1994

- Making of Modern Law – ACLU Papers, 1912-1990

- Independent Voices

- This collection of nearly 500 (and growing) underground newspapers and alternative magazines from the 1960s through the 1980s. The collection includes feminist periodicals, LGBT publications, military/GI newsletters, small-press literary magazines, and alternative campus/community newspapers. The costs of the collection are borne by participating libraries (including Georgetown), with the goal of making the collection entirely open access in 2019.

Relevant subject headings:

- Homosexuality — Law and legislation

- Gays — Legal status, laws, etc. — United States

- Homophobia — Law and legislation — United States

- Sex discrimination in criminal justice administration — United States

- Gays — Violence against — United States

- Hate crimes — United States

The Stonewall Riots

In 1969, a riot at the Stonewall Inn (later known as the Stonewall Riots) became a turning point. Though few records of the actual raid and riots that followed exist, the oral history of that time has been captured by the participants — both those who rioted and the police. The Stonewall Riots ignited after a police raid took place at the Stonewall Inn. The tension from ongoing harassment galvanized the LGBTQ community to riot for six days. The protest through the streets of New York City is memorialized as the annual Gay Pride parades that are now celebrated around the world.

As one participant remarked: “It’s very American to say, ‘This is not right.’ It’s very American to say, ‘You promised equality. You promised freedom.’ And, in a sense the Stonewall Riots said, ‘Get off our backs. Deliver on the promise.’ So in every gay pride parade every year, Stonewall lives.” — Virginia Apuzzo in American Experience: Stonewall Uprising (complete transcript available here).

Library Resources:

- Protection of sexual minorities since Stonewall: progress and stalemate in developed and developing countries, K3242.3 .P76 2010

- Long before Stonewall: histories of same-sex sexuality in early America, HQ76.3.U5 H57 2007

- Toward Stonewall: Homosexuality and Society in the Modern Western World, eBook 2006

- Before Stonewall: the making of a gay and lesbian community, HQ76.8.U5 W43 1988

Harvey Milk

“I know that you cannot live on hope alone, but without it, life is not worth living. And you … and you … and you … have got to give them hope.” — Harvey Milk, “You Cannot Live on Hope Alone” speech.

When he won the election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977, Harvey Milk made history as the first openly gay elected official in California, and one of the first in the United States. His camera store and campaign headquarters at 575 Castro Street (and his apartment above it) were centers of community activism for a wide range of human rights, environmental, labor, and neighborhood issues. During his tenure as supervisor, he helped pass a gay rights ordinance for the city of San Francisco that prohibited anti-gay discrimination in housing and employment.

Harvey Milk has been honored twice under President Obama’s administration. First, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. In 2014, he was honored by the United States Postal Service with a Forever Stamp in 2014.

Library Resources:

- An archive of hope: Harvey Milk’s speeches and writings, F869.S357 M55 2013

- The 100 greatest Americans of the 20th century: a social justice hall of fame, eBook 2012

- The Harvey Milk interviews: in his own words, F869.S353 M5465 2012

- The times of Harvey Milk, DVD F869.S353 M549 2011

- Ripples of hope: great American civil rights speeches, eBook 2003 (also available in print)

- The trial of Dan White, KF221.M8 S24 1991

Library Special Collections

- Carol Ruth Silver Collection 1967-1972, National Equal Justice Library

- Carol Ruth Silver was a fellow supervisor and colleague of Harvey Milk. Her these materials include papers from her time working closely with fellow supervisor Harvey Milk and Georget Moscone including progressive legislative reform, and co-sponsoring an ordinance with Harvey Milk, which prohibited anti-gay discrimination in San Francisco.

National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights

Marches on Washington, D.C. can serve many functions: to protest peacefully, to make visible the commitment and volume of support behind a movement, to mobilize and nationalize otherwise more fractured, local efforts to organize. The LGBTQ community and its allies have marched on the nation’s capital on numerous occasions, beginning with a march and rally that took place on October 14, 1979.

The organizers identified the following Five Demands:

- Pass a comprehensive lesbian/gay rights bill in Congress.

- Issues a presidential executive order banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in the Federal Government, the military and federally-contracted private employment.

- Repeal all anti-lesbian/gay laws.

- End discrimination in lesbian mother and gay father custody cases.

- Protect gay and lesbian youth from any laws which are used to discriminate against, oppose and/or harass them in their homes, schools, jobs and social environments.

Subsequent marches have taken place in 1987, 1993, 2000, and 2009.

Library Resources

- Queer mobilizations: LGBT activists confront the law, KF4754.5 .Q44 2009

- The dividends of dissent: how conflict and culture work in lesbian and gay marches on Washington, HQ76.8.U5 G53 2008

Subject Headings

- Gay liberation movement — Washington (D.C.) — History

- Civil rights demonstrations — Washington (D.C.) — History

- Gays — United States — Washington (D.C.) — Political activity

Other Resources

The HIV/AIDS Epidemic

The United States was the focal point of the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. The disease was first noticed en masse by doctors who treated gay men in Southern California, San Francisco, and New York City in 1981. When cases of AIDS first emerged in the U.S., they tended to originate among either men who had sex with other men, hemophiliacs, and heroin users. The fact that the disease was also prevalent among Haitians led to the “Four-H Club” of groups at high risk of AIDS. Though some believe that AIDS began in the U.S.A. in the 80’s, the truth is that it this is when people became aware of HIV and when it gained recognition as a health condition. It is believed to have been in the U.S. long before that – perhaps as early as the 1960s. The first reported cases of HIV are believed to have come from Kinshasa in or around 1920. It was transferred from monkeys and chimps to humans.

The prevalence of the disease among gay men in the U.S. in the 80s and 90s initially resulted in a stigma against homosexuals and a general fear and misunderstanding regarding how AIDS was spread. However, as celebrities like Rock Hudson and Freddie Mercury revealed that they had the disease, and Magic Johnson came forward with HIV, and dedicated his retirement to educating others about the virus, attitudes began to change. In 2010, a U.S. travel ban on HIV-positive people that had been in effect since 1987 was lifted, allowing them to finally enter the country without a waiver.

Notable Supreme Court Cases

- Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624 (1998) – in this case, the Court held that reproduction does count as a major life activity under the Americans with Disability Act of 1990 (ADA) and that those with HIV are covered under the ADA even if they have not yet manifested visible symptoms or illness.

Library Resources

- Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, RA644.A25 S48 1987

- Nan D. Hunter and William B. Rubenstein, eds., AIDS Agenda: Emerging Issues in Civil Rights, RC607.A26 A535 1992

- James F. Keenan et al., eds., Catholic Ethicists on HIV/AIDS Prevention, RA644.A25 C376 2000

- Margaret C. Jasper, AIDS Law, KF3803.A54 J37 2008

The 1990s, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and DOMA

The 90’s were a pivotal time for gay rights. While LGBTQ people were treated unequally, and often faced violence within their communities, a younger generation began to realize that LGBTQ people were entitled to the same rights as anyone else. While it would take another 20 years or so for those rights to be realized, the 90’s were a time when gay rights began to be on the forefront of political conversations.

In 1993, the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was instituted within the U.S. military, permitting gays to serve in the military but banning homosexual activity. President Clinton’s original intention to revoke the prohibition against gays in the military was met with stiff opposition; this compromise, which led to the discharge of thousands of men and women in the armed forces, was the result.

On April 25, an estimated 800,000 to one million people participated in the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. Several events such as art and history exhibits, public service outings and workshops were held throughout Washington, DC leading up the event. Jesse Jackson, RuPaul, Martina Navratilova, and Eartha Kitt were among the speakers and performers at a rally after the march. The march was a response to “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell”, Amendment 2 in Colorado, and rising hate crimes and ongoing discrimination against the LGBT community.

Speaking of Amendment 2 in Colorado, it sought to deny gays and lesbians protection against discrimination, claiming that such rights were “special rights.” The Supreme Court struck it down in 1996, the same year that DOMA came into being. In Romer v. Evans, the Supreme Court stated, “We find nothing special in the protections Amendment 2 withholds. These protections . . . constitute ordinary civil life in a free society.”

The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was enacted in 1996 and defined marriage, at the federal level, as the union of one man to one woman. DOMA was primarily brought about by a fear that if states granted same-sex couples the right to marry, the federal government, and other states would have to honor those marriages. In 1996, this was an idea that didn’t sit well with the majority of Congress (it should be noted that Congress was held by a Republican majority at that time). DOMA allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states. More starkly speaking, until Section 3 of the act was struck down in 2013 by the decision in United States v. Windsor, DOMA effectively barred same-sex married couples from being recognized as “spouses” for the purposes of federal marriage benefits. While DOMA did not bar individual states from recognizing same-sex marriage, it imposed constraints on the benefits that all legally married same-sex couples could receive.

These benefits included insurance benefits for government employees, social security survivors’ benefits, immigration assistance, ability to file for joint bankruptcy, and the filing of joint tax returns, financial aid eligibility otherwise available to heterosexual married couples, and other laws that applied to heterosexual married couples. In 2004, a General Accounting Office report looked at all federal statutes and found 1,138 federal laws using terms like “spouse,” “husband,” “wife,” “widow” or “widower,” that treat people differently based on whether or not the federal government recognizes them as married.

In the lead-up to the Windsor decision, the Obama administration stopped defending Section 3 of DOMA in court challenges because the President and the Department of Justice determined that it was clearly unconstitutional. Attorney General Eric Holder notified Congress that the DOJ would no longer argue that Section 3 of DOMA should be upheld in cases challenging it. The President and Attorney General had concluded that laws that discriminate against LGBT people required the application of heightened scrutiny under the Constitution’s Equal Protection guarantee, meaning that courts must presume such laws unconstitutional and strike them down unless there was a very strong justification for the discrimination. The President and Attorney General concluded that DOMA could not survive that test. Although the administration stopped defending DOMA Section 3 in legal cases, it continued enforcing the law until the Windsor decision came out.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996) – this case held that a state constitutional amendment in Colorado preventing protected status based upon homosexuality or bisexuality did not satisfy the Equal Protection Clause. The state constitutional amendment failed rational basis review.

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 12 (2013) – in this case, the Court held that Section 3 of DOMA was unconstitutional. Specifically, the Court found DOMA to offend the Constitution because, “By history and tradition the definition and regulation of marriage . . . has been treated as being within the authority and realm of the separate States…”

Library Resources:

- John D’Emilio et al., eds., Creating Change: Sexuality, Public Policy, and Civil Rights, HQ76.8.U5 C74 2000

- William D. Araiza and Dan Woods, Understanding the Repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell: An Immediate Look at Policy Changes Allowing Gays and Lesbians to Openly Serve in the Military, KF7265 .A965 2011

- Roberta A. Kaplan with Lisa Dickey, Then Comes Marriage: United States v. Windsor and the Defeat of DOMA, KF229.W56 K37 2015

- William H. Manz, ed., Defense of Marriage Act: A Legislative History of Public Law 104-199 – HeinOnline

Additional Resources:

- The Repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” – Human Rights Campaign

- FAQ on DOMA – GLAAD

- DOMA – Lambda Legal blog

Lawrence v. Texas

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) is a landmark case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2003. The Court held that a Texas statute criminalizing intimate, consensual sexual conduct was a violation of the Due Process Clause. The statute at issue originally criminalized any oral and anal sexual activity. However, it was rewritten to apply only to homosexual conduct. Lambda Legal represented the defendants. Their goal was to not only challenge the Texas statute, but also all 13 laws still enforceable in states. The defendants pled no contest from the beginning, which allowed them to challenge the law without disputing the facts. The risk for the defendants and the LGBTQ community more generally, was a repeat from 17 years earlier with the Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 187 (1986) decision.

In Bowers v. Hardwick, the Court held this activity was not constitutionally protected, and individuals could be arrested for engaging in consensual, sexually intimate acts in their own homes.

In the majority opinion of Lawrence, Justice Kennedy began with the following lines:

Liberty protects the person from unwarranted government intrusions into a dwelling or other private places. In our tradition the State is not omnipresent in the home. And there are other spheres of our lives and existence, outside the home, where the State should not be a dominant presence. Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct. The instant case involves liberty of the person both in its spatial and more transcendent dimensions.

He made clear that adults are free to engage with one another in the privacy of their own homes “without intervention of the government.” He added that the “Texas statute furthers no legitimate state interest which can justify its intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual.” The Court added that “Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

The Court reiterated the principles outlined in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992): “our laws and tradition afford constitutional protection to personal decisions related to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing, and education.” And continued by stating that “[p]ersons in a homosexual relationship may seek autonomy for these purposes, just as heterosexual persons do. The decision in Bowers would deny them this right.”

The language of the Lawrence decision provided a foundation that has allowed for continued progress in civil rights for the LGBTQ community.

Library Resources

- Flagrant conduct: the story of Lawrence v. Texas: how a bedroom arrest decriminalized gay Americans, KF224.L39 C37 2012

- The case for gay rights: from Bowers to Lawrence and beyond, KF4754.5 .R525 2005

Proposition 8

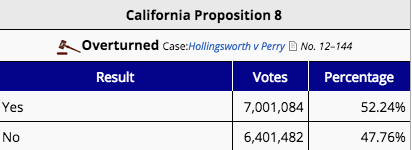

California has always been thought of as a progressive state. In general, the west coast is seen as more liberal than the southeastern seaboard. However, events arose surrounding gay rights in 2008 in California that threw its stance as a bastion of liberal progressivism into question. Proposition 8, known colloquially as Prop 8, was a California ballot proposition and a state constitutional amendment passed in the 2008 California state election. The proposition was created by opponents of same-sex marriage before the California Supreme Court issued its ruling on In re Marriage Cases. This decision found the 2000 ban on same-sex marriage, Proposition 22, unconstitutional. In the long run, Prop 8 was ruled unconstitutional by a federal district court in 2010, although that decision did not go into effect until 2013, following the conclusion of Prop 8 advocates’ appeals, which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Prop 8 negated the In re Marriages Cases ruling by adding the same provision as Proposition 22 to the California Constitution, providing that “only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” As an amendment, it was ruled constitutional by the California Supreme Court in 2009, on the grounds that it “carved out a limited [or ‘narrow’] exception to the state equal protection clause.” One justice dissented, noting that exceptions to the equal protection clause could not be made by any majority since its whole purpose was to protect minorities against the will of a majority. One reason that Prop 8 was upheld by the Supreme Court while Proposition 22 was not rests in the fact that Proposition 22 was only a statute while Prop 8 was an amendment to the state constitution. Statutes do not have the same weight as constitutional amendments – which would arguably be a reason to overturn Prop 8 all the more. But in this instance, the court saw it as a reason to uphold the will of the voters.

Among the advocates for Prop 8 were religious organizations, most notably the Roman Catholic church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. While it is estimated that Catholic Archbishops and lay organizations were able to donate about $3 million to Prop 8, Mormons contributed over $20 million, a good part of that coming from Utah. LDS church members were said to be about 80 to 90% of the volunteers for door-to-door canvassing.

Once Prop 8 had been upheld by the state courts, two same-sex couples filed a lawsuit against Prop 8 in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in Hollingsworth v. Perry. In August of 2010, Chief Judge Vaughn Walker ruled that the amendment was unconstitutional under both the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, since itremoved rights from a disfavored class with no rational basis. The state government supported the ruling and refused to defend the law.The ruling was stayed pending appeal by advocates of Prop 8. In 2012, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, in a 2-1 decision, reached the same conclusion as the district court, but on different, narrower grounds. The court ruled that it was unconstitutional for California to grant marriage rights to same-sex couples, only to take them away shortly after. This ruling was then stayed pending appeal by Prop 8’s advocates to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On June 26, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Hollingsworth v. Perry, ruling that proponents of initiatives like Proposition 8 did not possess legal standing to defend the resulting law in federal court. Therefore, the Supreme Court vacated the decision of the Ninth Circuit, and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Ninth Circuit, on remand, dismissed the appeal for lack of jurisdiction. This left the 2010 decision of the district court as the binding decision. Thus, Prop 8 was held unconstitutional and Governor Brown was free to permit same-sex marriages to recommence.

Notable Supreme Court Cases:

- Hollingsworth v. Perry, 133 S. Ct. 2652 (2013) – this case dealt with the Prop 8 litigation coming out of California. The Court held that, as private parties with a “generalized grievance,” the Prop 8 proponents did not have standing to appeal the District Court ruling. The Court explained that Article III of the Constitution confines the power of the federal courts to deciding actual “cases” or “controversies.” Once the District Court issued its order, the Prop 8 proponents “no longer had any injury to redress,” and that “no matter how deeply committed petitioners may be to upholding Proposition 8,” their interest was insufficient to confer standing. Given its ruling, the Supreme Court left the District Court’s opinion – that Prop 8 violated the Fourteenth Amendment – as the final and controlling decision on the merits.

Library Resources:

- Anqi Li, Uses of History in the Press and in Court During California’s Battle Over Proposition 8: Casting Same-Sex Marriage as a Civil Right, HQ1034.U5 L52 2012

- David Boies and Theodore B. Olson, Redeeming the Dream: The Case for Marriage Equality, KF228.H645 B65 2014

- Kenji Yoshino, Speak Now: Marriage Equality on Trial: The Story of Hollingsworth v. Perry, KF228.H645 Y67 2015

Obergefell v. Hodges

Same-sex marriage has been controversial for decades, but tremendous progress was made across the United States as states individually began to lift bans to same-sex marriage. Before the landmark case Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015) was decided, over 70% of states and the District of Columbia already recognized same-sex marriage, and only 13 states had bans. Fourteen same-sex couples and two men whose same-sex partners had since passed away, claimed Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee violated the Fourteenth Amendment by denying them the right to marry or have their legal marriages performed in another state recognized.

All district courts found in favor of the plaintiffs. On appeal, the cases were consolidated, and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and held that the states’ bans on same-sex marriage and refusal to acknowledge legal same-sex marriages in other jurisdictions were not unconstitutional.

Among several arguments, the respondents asserted that the petitioners were not seeking to create a new and nonexistent right to same-sex marriage. Justice Kennedy, writing for the majority, noted that, “while that approach may have been appropriate for the asserted right there involved (physician-assisted suicide), it is inconsistent with the approach this Court has used in discussing other fundamental rights, included marriage and intimacy.” He outlined that:

Loving did not ask about a “right to interracial marriage”, Turner did not ask about a “right of inmates to marry”, and Zablocki did not ask about a “right of fathers with unpaid child support duties to marry.” Rather, each case inquired about the right to marry in its comprehensive sense, asking if there was a sufficient justification for excluding the relevant class from the right … That principle applies here. If rights were defined by who exercised them in the past, then received practices could serve as their own continued justification and new groups could not invoke rights once denied.

Efforts to quantify the impact of Obergefell include a June 2016 report drafted by the Williams Institute: UCLA School of Law. According to the report, “weddings by same-sex couples have generated an estimated $1.58 billion boost to the national economy, and $102 million in state and local sales tax revenue since the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision extending marriage equality nationwide in June 2015.” Over 130,000 same-sex couples married, bringing the total of same-sex couples in the U.S. to nearly 500,000.

In Obergefell, Justice Kennedy concluded:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideal of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded form one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

Library Resources

- Love unites us: winning the freedom to marry in America, KF539 .L68 2016

- American constitutionalism, marriage, and the family: Obergefell v. Hodges and U.S. v. Windsor in context, KF229.W56 A44 2016

- Love wins: the lovers and lawyers who fought the landmark case for marriage equality, KF229.O24 C46 2016

A Timeline of the Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage in the U.S.

- 1970 – A same-sex couple in Minnesota applies for a marriage license. They are denied and their case goes to the state Supreme Court.

- 1973 – Maryland becomes the first state to ban same-sex marriage

- 1976 – a non-church sanctioned gay wedding makes news

- 1983 – ‘spousal’ rights of same-sex couples become an issue – a lesbian couple is confronted with the spousal rights issue when one of them is in a car accident and the other is denied the right to care for her.

- 1984 – Berkeley, CA passes the nation’s first domestic partnership law

- 1987 – first mass same-sex wedding ceremony – occurs on the National Mall – nearly 2000 same-sex marriages take place

- 1989 – court rulings in NY and CA define same-sex couples as families

- 1992 – same-sex employees begin to receive domestic partner benefits from Levi Strauss & Co. and the state of Mass.

- 1993 – the Hawaii Supreme Court rules that same-sex marriages cannot be denied unless there is a “compelling” reason to do so – Hawaii legislators respond by passing an amendment to ban gay marriage

- 1995 – Utah governor signs a state DOMA statute into law

- 1996 – President Clinton signs the federal DOMA

- 1997 – Hawaii becomes the first state to offer domestic partnership benefits to same sex couples

- 1998 – Alaskan and Hawaiian voters approve state constitutional bans on same-sex marriage

- 1999 – Vermont’s Supreme Court rules that same-sex couples must receive the same benefits and protections as any other married couple under the Vermont Constitution

- 2000 – the Central Conference of American Rabbis agrees to allow religious ceremonies for same-sex couples while Vermont becomes the first state to pass a law granting the full benefits of marriage to same-sex couples. Nebraska voters approve a state constitutional ban on same-sex marriage

- 2002 – Nevada votes to approve a state constitutional ban on same-sex marriage

- 2003 – A proposed amendment to the federal Constitution is introduced to the House of Representatives. It would define marriage as only between a man and a woman. The U.S. Supreme Court decides Lawrence v. Texas, striking down sodomy law and enshrining a broad constitutional right to sexual privacy. California passes a domestic partnership law which provides same-sex partners with almost all the rights and responsibilities as spouses in civil marriages. President Bush states that he wants marriage reserves for heterosexuals and the Massachusetts Supreme Court hands down a decision that makes Massachusetts the first state to legalize gay marriage.

- 2004 – The city of San Francisco begins marrying same-sex couples in an open challenge to CA law and New Mexico begins issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples as their law does not mention gender. Portland, Oregon also begins issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. A poll taken by the Washington Post shows that 51% of the country favors allowing same-sex couples to form civil unions. While San Francisco is told to halt same-sex unions, Oregon takes the more drastic step of halting all marriages until the state decides who can and cannot wed. The proposed constitutional amendment with the same-sex ban dies in the U.S. Senate after testimony against it from conservative politicians. Missouri votes to ban same-sex marriage. Washington state says yes to same-sex marriage in a court decision while the California Supreme Court voids same-sex marriages. Several states pass initiatives to ban same-sex marriages.

- 2005 – In New York, a state judge calls the state ban on same-sex marriage illegal. California’s legislature attempts to pass a law legalizing same-sex unions but it is vetoed by the governor. Connecticut becomes the second state to approve same-sex unions.

- 2006 – The New Jersey Supreme Court orders the legislature to recognize same-sex unions.

- 2008 – California’s Supreme Court overturns the ban on gay marriage. This leads to California voters approving a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. Florida and Arizona voters do the same.

- 2009 – The Iowa Supreme Court overturns the state ban on same-sex marriage. Vermont’s legislature legalizes same-sex marriages. Maine and New Hampshire follow suit, though Maine voters later repeal the state law allowing same-sex marriage.

- 2010 – California’s voter-passed ban on same-sex marriage from 2008, known as Prop 8, is declared unconstitutional.

- 2011 – President Obama declares DOMA unconstitutional. New York legalizes same-sex marriage.

- 2012 – The Ninth Circuit finds Prop 8 unconstitutional. Washington state, Maine, and Maryland legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote.

- 2013 – Rhode Island, Delaware, Minnesota, New Jersey, Hawaii, Illinois, and New Mexico legalize same-sex marriage. The U.S. Supreme Court finds Section 3 of DOMA unconstitutional. It also decides the Prop 8 defenders lack standing, clearing the way for same-sex unions to be legalized in California. The IRS recognizes same-sex married couples. Utah’s same-sex marriage ban is found unconstitutional.

- 2014 – Oregon, Pennsylvania, Kansas, and South Carolina legalize same-sex marriage. The Presbyterian church votes to allow same-sex ceremonies. The U.S. Supreme Court decides a case that allows for same-sex marriage in 5 states (VA, OK, UT, WI, and IN) but declines to make a blanket statement for all states.

- 2015 – The U.S. Supreme Court makes same-sex marriages legal in all 50 states in Obergefell v. Hodges.

It is only fitting to end this timeline with the following quote from that decision:

“No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

Civil Rights for the Disabled

Overview

The fight for rights for disabled people slowly took shape in the United States, beginning in the early 1800s. Well-known persons such as Louis Braille and later, Helen Keller, made significant individual progress, and helped to focus attention on the issue of rights for disabled Americans. Gradually, local and statewide organizations were formed, where mostly family and friends took up the charge. The first national organization for disabled rights was founded in 1880–The National Association of the Deaf. Early 20th-century legislation and litigation regarding disabled persons involved awards to governmental or other organizational bodies to encourage or reward programs for the handicapped. For example, during the 1930s, The Social Security Act provided funds to states for assistance to blind individuals and disabled children. In the ’40s, President Truman signed the National Mental Health Act, which called for the establishment of a National Institute of Mental Health, and The American Federation of the Physically Handicapped became the first cross-disability national rights for the disabled organization. In the 50s, the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education picked up the momentum of the disability rights movement. And the Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave the movement a goal.

Library Resources:

- Doris Zames Fleischer, The Disability Rights Movement: From Charity to Confrontation, HV1553 .F58 2011

- Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States, HV1553 .N54 2012

- Chris Mounsey, ed., The Idea of Disability in the Eighteenth Century, PN56.5.H35 I34 2014

Disability Rights in the 1960s and 70s