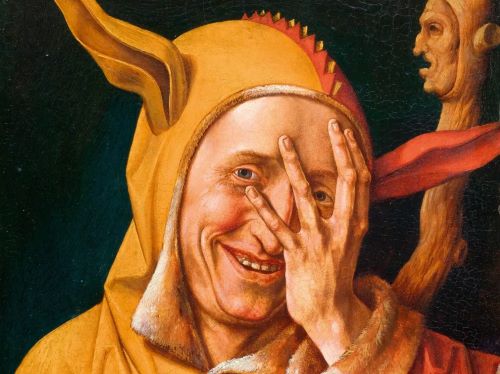

The figure of the fool from the medieval era.

By Julia Binswanger

Freelance Journalist and Audio Producer

While the fool is often associated with the Middle Ages, the figure’s role evolved a great deal in the centuries that followed. Now, an exhibition at the Louvre in Paris is celebrating the complex character, following the fool’s dance through art history.

Titled “Figures of the Fool: From the Middle Ages to the Romantics,” the show features eight sections that examine the fool in different contexts—such as “In the Beginning: The Fool and God,” “The Fool and Love,” “The Fool at Court” and “Fools in the City”—to teach visitors how the character changed with the times.

“The figure of the fool walked off the margins of medieval manuscripts into the unholy courts of the Renaissance, then returned to the page as Hamlet’s Yorick,” writes the Wall Street Journal’s Dominic Green. “Later, in the age of reason and democracy, the parodist of royal dignity became a mirror of the universal condition: Dostoevsky’s ‘holy fool’ and Picasso’s grubby clowns; Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.”

Museumgoers can peruse more than 300 pieces of art from 90 European and American institutions. These items follow the fool across hundreds of years, beginning in the Middle Ages and ending in the 19th century.

“Such characters appear in architectural adornments, frescoes, tapestries, etchings, ceramics and ivory or carved-wood miniatures, or in chess sets as an alternative to the bishop,” writes Artforum’s Charlotte Kent. “Fools came from all social strata. One drawing has them falling from trees; an anonymous Netherlandish oil on panel shows fools hatching from eggs beneath an enormous chicken.”

Later depictions often portray the fool as someone to relate to rather than someone to mock. As the Louvre explains on the exhibition website, the character “became a figure with which artists identified, wondering: ‘What if I were the fool?’”

Many of the fools in the exhibition wear bright, colorful outfits and evoke a sense of levity. But many others don’t fit this stereotype, appearing morose or burdened.

In Jan Matejko’s 1862 depiction of Stańczyk, a famous Polish court jester, the figure sits slumped over in a chair, “having just discovered—presumably indicated by papers on the table—that the Polish city of Smolensk has been lost (1514) during war with Moscow,” per Encyclopedia Britannica. Behind him, the rest of the court enjoys a ball.

“The fool allows for a figurative representation of questions troubling society,” Elisabeth Antoine-König, one of the exhibition’s curators, tells Artnet’sDevorah Lauter. She adds that the fool is “one thing and its opposite, he is the rejected marginalized figure, and the one who unites us and bears the ridicule and anger of others.”

These days, most of us don’t want to be called a fool. Still, the exhibition’s curators think modern audiences have a lot to learn from the character. “I feel that the figure of the fool, as it existed in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, is lacking today, in helping us face the crises we are experiencing,” Antoine-König adds.

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine, 01.08.2025, reprinted with permission under a Creative Commons license for educational, non-commercial purposes.