The French photographer Eugène Atget captured the city at a moment of rapid transition.

By Antares Wells

Curatorial Assistant

J. Paul Getty Museum

The entrance to a bar. Courtyards with wooden carts at rest. A door knocker held in a lion’s mouth. Mannequins in shop windows.

These are just some of the everyday details captured by French photographer Eugène Atget in his obsessive documentation of Paris and its environs.

Atget made thousands of photographs from the late 1880s until his death in 1927, offering a fascinating glimpse into life in the French capital at a time of rapid urban transition.

In 2022, the Getty Museum acquired over 200 photographs by Atget, assembled over two decades by collectors Mary and Dan Solomon. For the past few months, I’ve been cataloging this collection with the aim of making it accessible to the public.

Here are 10 photographs that caught my eye.

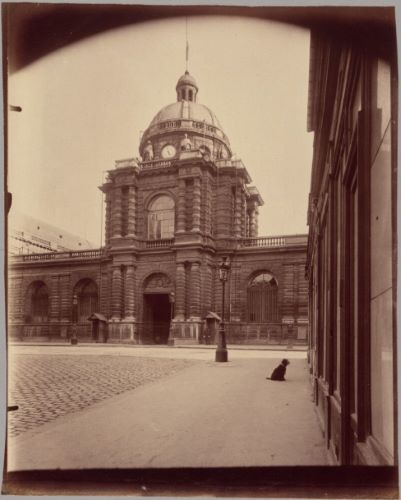

Atget described his photographs as “simply documents I make,” claiming to have no grand pretensions to making art. Despite this, his compositions are often surprising. By including a small dog in the frame, this view of the imposing Senate building at Luxembourg Palace (formerly a royal residence and later a prison during the French Revolution) becomes a humorous study of scale.

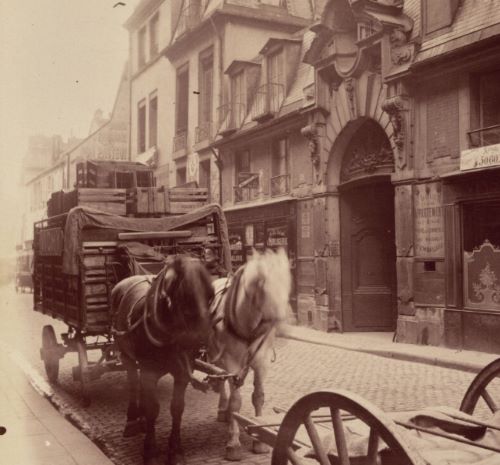

This photograph has the immediacy of a film, transporting you to the heart of Paris’s historic textile district. The strong lines of movement in the foreground—with the horse and cart seeming to trot forward, out of the frame—remind me of Gustave Caillebotte’s paintings of Parisian thoroughfares in the 1870s, such as Le Pont de l’Europe and Rue de Paris, temps de pluie.

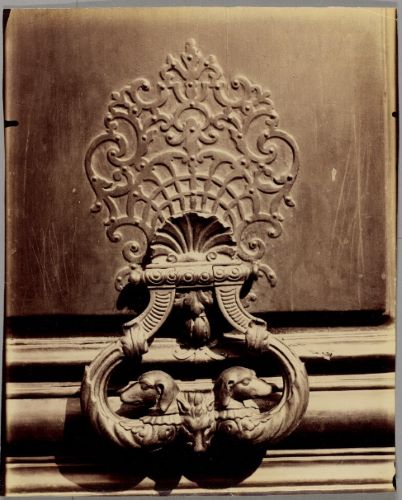

Atget made his photographs with a wide range of clients in mind, including illustrators, set designers, cartoonists, and painters. By isolating architectural elements such as door knockers, staircases, and balconies, artists could study these details for use in their own work. This ornate knocker, featuring the profiles of two dogs on either side of a fox, adorned a door of a 17th-century mansion known as the Hôtel du Grand Veneur, honoring a military officer who organized hunting expeditions for the French King.

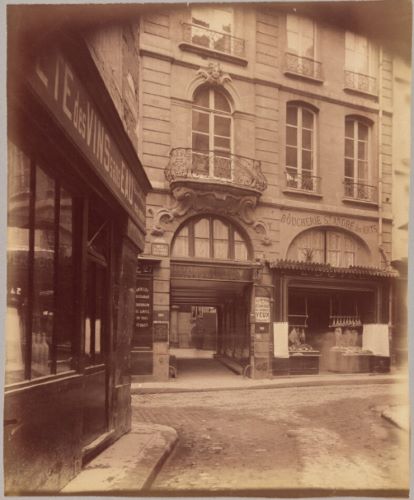

Handwritten notations on the back of this photograph indicate that Atget was particularly focused on the ornate balcony of this Baroque building, likely for clients interested in architecture. But the image is also rich in other details, such as carcasses hanging in the window of a butcher shop and bottles of wine lined up in a bar on the corner. This photograph was included in an album entitled Vieux Paris (Old Paris), compiled by Atget and comprising views of the city’s courtyards, churches, and cobblestone streets.

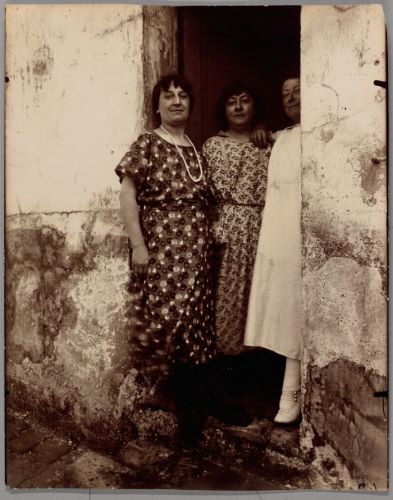

In the early 1920s, Atget made a series of photographs of sex workers outside brothels on the infamous rue Asselin. It is thought that the painter André Dignimont commissioned him to provide source material for his book La Femme criminelle (The Criminal Woman). As with several of the other photographs in this short-lived series, the women hold their own, meeting the camera with frankness and a hint of a smile. This one is particularly striking for the sense of unity and bond between the women, and the richness of patterns and textures in the composition—from the fabrics of the women’s dresses to the rough facade of the building.

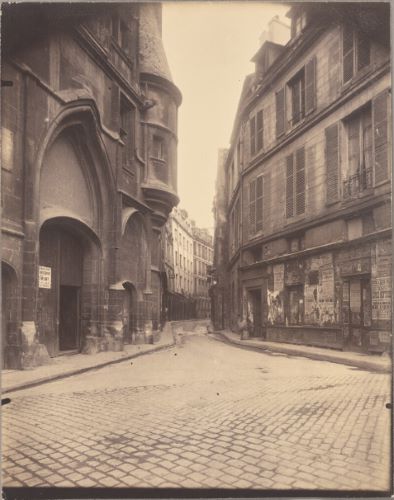

Atget made his photographs with a heavy view camera mounted on a tripod, using glass plate negatives (it’s even said that he rejected surrealist artist Man Ray’s offer of a modern Rolleiflex). As a result, his street views capture the details of advertisements, signage, and architecture with remarkable clarity. This photograph of rue du Figuier, in the Marais district, hints at the area’s Jewish community, with posters in Yiddish pasted on the facade of the apartment building on the right.

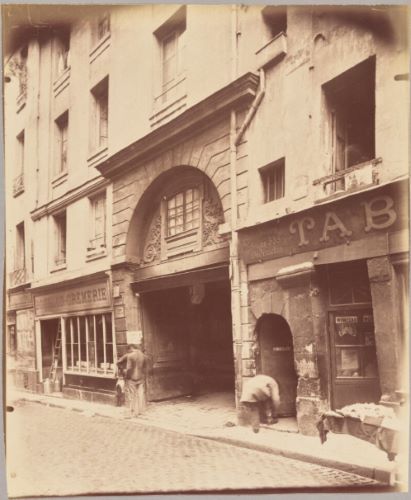

As Atget elected to make his photographs of facades and shopfronts in the early hours of the morning, there are few people in his street views. When people are included, they often register as a blur. But this man bending over in a doorway, apparently tying his shoelace, made it into the picture—recalling inventor Jacques-Louis-Mandé Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple, thought to be the earliest surviving photograph of a human being: a man getting his shoes shined.

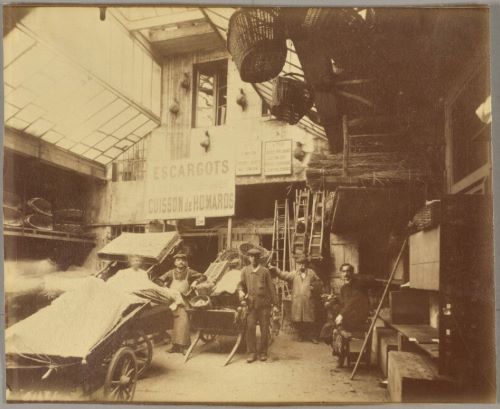

This photograph of a group of workers clustered in the delivery area of a hotel appears, at first glance, to resemble many other early documentary photographs of warehouses…if not for the large snails climbing up the back wall!

A sign declares the specialty of the business: cooking “ESCARGOTS,” and two of the employees hold shellfish. Atget captures the group full of pride in their work, looking back at the camera with an air of self-possession.

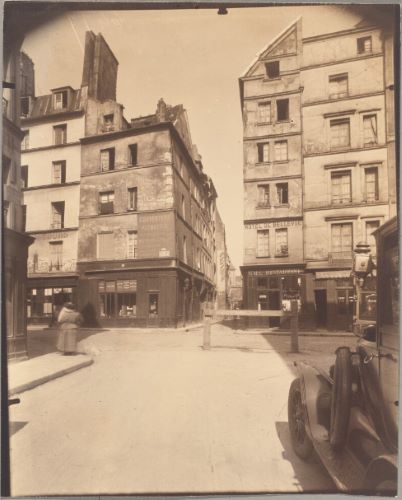

In 1931, writer Camille Recht likened Atget’s images to “police photographs of a crime scene.” Though Recht was referring primarily to Atget’s domestic interiors, his photographs of largely vacant streets also attracted attention in this vein. This view of an intersection, with a woman standing at the street corner, supporting a child on her shoulder, feels forensic—not least due to the car appearing to lurk in the bottom right, facing a street partially closed to traffic.

In 1909, Atget began to document the homes of Parisians in a series now known as Interiors, photographing 10 apartments in total, including his own. Each photograph allows our eyes to roam over private rooms that evoke the personalities of their residents, while suggesting the ways social class manifests in domestic spaces. This photograph of the bedroom of “Madame Dubois,” described as a “woman with a small private income,” allows us a glimpse not only into her life, but a peek at the elusive figure of Atget himself, shrouded in the black sheet of his camera and reflected in Madame Dubois’s mirror.

Originally published by The Iris, 09.28.2023, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.