Punishments were neither consistent nor logical.

By Dr. Jen Baker

Teaching Fellow in 19th- and 20th-Century Literature

University of Warwick

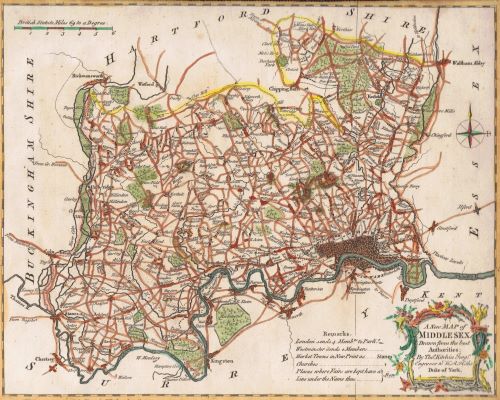

Records from the Old Bailey proceedings (the Central Criminal Court for England and Wales) indicate that the acknowledgement and subsequent punishment of sexual offences against children are not modern phenomena. Between 1674 and 1913 – when online public records cease – there are at least 570 documented cases, predominantly from the City of London and Middlesex, involving adults accused of sexual relations with children.

Punishments were neither consistent, nor did they appear more logical and “just” (by modern standards) as time progressed. The limited and selective information recorded tended to caricature those involved, and rarely involved a full transcription of evidence given or dialogue encountered. In one of the earliest cases, from 1678, an apprentice described as “a lusty Lad of About 17 or 18 years” was “Condemn’d to Dye” for “a filthy bruitish offence […] for having the Carnal knowledge of a Maiden Child, under the Age of Ten years”. The sentence leading into the particulars makes clear that the record will not discuss any information that was too distressing or uncivilised; “The case was thus, (as far as ’tis necessary or fit with modesty to be related).”

Such cases suggest that any form of forceful and sexual interaction with a child was considered an abhorrent act, and yet a number of cases also show that the child was not always believed unreservedly. In the case of Mr Valenciens in 1679, for example, the court felt that “the 2 Girls pretended abundance of modesty in giving their evidence, yet in fine, each of them down right swore the matter of Fact but the same was attended with many improbable and suspicious circumstances”. The court further believed their mother had deliberately attempted to ruin the defendants reputation in order to gain money and he was subsequently acquitted.

The argument concerning “consent” and a child’s right to engage in such activity was as relevant in the earliest of these documented cases as today. For instance Stephen Arrowsmith was condemned to death for the rape of a girl aged nine years old, despite the girl testifying that she had concealed the crime because “she took Pleasure in it”. The court, however, was not swayed in the defendant’s favour, finding “that [the girl’s] consent would not save him, for the Statute provides, that a Child under 10 years of age, should not be abused with, or without her Consent.”

A few cases can be found in the Old Bailey in which the court was not always sure whether the defendant had actually been sexually involved with the child. One particularly interesting case is that of Samuel Eales (1694) found irrefutably “not guilty”, for the defence had proven that the nine-year-old girl “was of Evil Repute”. Such remarks were not followed up upon, nor can I find public reaction to this, but offer an interesting parallel to a recent case.

In 2008, British newspapers reported on an incident in which an eleven-year-old girl accused a twenty-year-old man of sexually assaulting her. Much was made of the judge’s remarks. Although the man had admitted to engaging in sexual relations with her, the girl expressed herself, according to the judge, “in relation to sexual matters with an awareness which would make many twice her age blush and one hopes would be rare for an 11-year-old to experience.” When the case resurfaced this year, a range of newspapers, and subsequently child protection groups, expressed outrage at what was described as an allusion to the “asking for it” attitude that has been at the centre of the rape narrative debate and a resurgence of “Lolita-syndrome” – a position that children can be precocious and predatory.

When compared to the 1694 Eales case, the judge in 2008 may seem positively antiquated, and the road to justice stilted and contradictory. And yet, these are both complicated instances in which the supposed “purity” of childhood, and the militant belief that adults are the only ones to hold the power in adult-child relationships, is questioned. It is interesting too to link back to the Stephen Arrowsmith case of 1678. The Chaplain’s record (known as the Ordinary’s account) noted that despite “willingness” being the defence in a few cases, consent “from those so young is reasonably presum’d to proceed from an innocent Indiscretion and Ignorance of what they are tempted to.” The law therefore acquiesced that children had sexuality, but, unlike the judge in the 2008 case, differentiated between possessing sexuality and understanding the implications, leaving the question of which period appears more progressive, balancing precariously.

Originally published by NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality, 01.25.2014, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.