By Dr. Rick Musser

Professor Emeritus of Journalism

University of Kansas

Introduction

This article focuses on American journalism from 1900-1999. Although history does not often compartmentalize itself into convenient pieces, this focuses on the 10 decades as if each 10 years were a chapter.

From the first newsreels to the advent of the Internet, the 20th century will be remembered for the birth, evolution and impending demise of “modern,” mainstream journalism. While this article concentrates on American journalists and news services, the contributions from other parts of the world also are recognized.

The 1900s

Overview

Immigration and industry both boomed in the United States in the 1900s. These immigrants, seeking better opportunities in the U.S., found hazardous working conditions in factories and squalid living conditions in tenements. Big business led to big questions for many journalists of the 1900s. From Upton Sinclair’s book, The Jungle to Ida Tarbell’s investigation of John D. Rockefeller, newspapers and magazines in the 1900s were full of exposés. President Theodore Roosevelt described these journalists as muckrakers.

In the quest for increased readership, newspaper editors began to publish sensational headlines and lurid stories. The age of yellow journalism was in full flower.

International communication was made advanced by Guglielmo Marconi, who sent the first radio transmission across the Atlantic Ocean. Thomas Edison harnessed electricity and started one of the first movie companies. His execution movie told the tale of President William McKinley’s assassin’s death.

Journalists and Media Personalities

A Hungarian immigrant with few resources, Pulitzer rose to purchase the struggling New York World newspaper in 1883 after many successes in St. Louis. Pulitzer used his newspapers to crusade for the rights of immigrants, the poor and the working class. Sensational headlines such as “Baptized in Blood” competed with those of the New York Journal owned by William Randolph Hearst.

William Randolph Hearst, the only son from a rich family, took control of his father’s newspaper in 1887 after an unsuccessful stint at Harvard. Hearst became a major competitor of Joseph Pulitzer when he purchased The New York Journal in 1895. Under Hearst’s direction, the paper fanned the flames of war, urging it’s readers to “Remember the Maine”, a U.S. navy ship that exploded mysteriously in Cuba. Hearst’s efforts contributed to the start of the Spanish-American War. Hearst is quoted as saying, “War makes for great circulation.” Hearst used the expansion of his newspaper chain to further his political ambitions, though without the same level of success as his media empire.

Creator of The Yellow Kid and Buster Brown comics. The Yellow Kid would symbolize the circulation wars between Pulitzer and Hearst; the comic appeared in both newspapers simultaneously. The term “yellow journalism” derives from his popular comic strip. Outcault’s creations also generated the first comic merchandising; key rings, statues and other Yellow Kid paraphernalia predated Happy Meals by decades.

New York Post reporter and managing editor of McClure’s Magazine. Steffens wrote a series of articles that exposed corruption in the local governments of Chicago, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Philadelphia and New York City; later collected in the book The Shame of the Cities (1904). The Struggle for Self-Government (1906) told of investigations of state politicians. He joined other muckrakers like Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker to form the American Magazine.

As a teenager, Ida Tarbell witnessed first hand the efforts of the Standard Oil Company’s efforts to monopolize oil production in Pennsylvania. Tarbell wrote The History of the Standard Oil Company articles in McClure’s Magazine criticizing the business practices of Standard Oil and its president, John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller responded to these attacks by describing her as “Miss Tarbarrel”.

A muckraker and novelist known for his best seller The Jungle, first serialized in 1905 by the socialist journal of tiny Girard, Kansas, Appeal to Reason. Upton Sinclair’s classic book described the unsanitary practices of a Chicago meat packing company and led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1906) and the Meat Inspection Act (1906).

“There was never the least attention paid to what was cut up for sausage; there would come all the way back from Europe old sausage that had been rejected, and that was moldy and white – it would be dosed with borax and glycerin, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption.”

Excerpt from The Jungle

A muckraker on the staff of McClure’s Magazine, Ray Stannard Baker joined Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell, William Allen White and others to found American Magazine in 1906. Baker’s articles investigated labor relations and race relations; the latter were collected together in Following the Color Line, illuminating Jim Crow laws, lynching, and poverty. Baker later served as press secretary to President Woodrow Wilson during the Paris Peace Treaty, and wrote a multi-volume biography of Wilson.

“But the mob wasn’t through with its work. Easy people imagine that, having hanged a Negro, the mob goes quietly about its business; but that is never the way of the mob. Once released, the spirit of anarchy spreads and spreads, not subsiding until it has accomplished its full measure of evil.

Excerpt from an article entitled What is Lynching?

A pseudonym for Elizabeth Cochrane, Nelly Bly is known for numerous journalistic and business accomplishments. As a reporter, Bly pioneered techniques in investigative journalism by faking her own insanity in order to go undercover in New York’s insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island. During her lifetime, Bly also circumnavigated the globe in 72 days, managed two multi-million dollar companies at the same time, and was the first female correspondent to cover the eastern front during World War I.

Political Scene

Theodore Roosevelt was the first U.S. president to have his career and life captured on film. When President William McKinley was assassinated at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, Vice-President Roosevelt took office.

Known for his “big stick” policy in international affairs, Roosevelt has been quoted saying, “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.”

After re-election in 1905, Roosevelt worked to bring a peace settlement to the Russo-Japanese War. Roosevelt also acquired the right for the U.S. to build a canal in Panama and visited the country, the first time a U.S. president had ever visited a foreign nation.

Roosevelt coined the phrase “muckraker” to describe investigative journalists who fueled the progressive era crusades. He also sued Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World for libel following the publication of an unfavorable editorial regarding the involvement of the United States in the Panamanian Revolution. The case was dismissed.

Social Climate

The turn of the century also marked the dawn of many new technologies. Inventors, scientists and industrialists were busy around the turn of the century developing inventions. Thomas Edison created moving pictures and harnessed electricity while the Wright Brothers spread their wings.

At the same time, millions of immigrants arrived on U.S. soil, mostly from southern and eastern Europe. Though most were farmers, a majority would only find factory jobs in eastern U.S. cities.

Technological breakthroughs in transportation, communication, mechanization and science fostered an industrialized society. Corporate consolidations ruled the day, and the working conditions of men, women and children as laborers were harsh and brutal. Boys as young as 12 years old commonly worked in dangerous conditions in the coal mining industry.

Races relations degraded following the Plessy vs. Ferguson of 1896 decision that legalized segregation. Jim Crow laws also marginalized African Americans, preventing them from voting, while also turning a blind eye to white violence.

One of the new media technologies — new storefront theaters dubbed nickelodeons — succeeded wildly as an innovative form of entertainment. Appearing first in 1905, nickelodeons featured movie shows all day long, in contrast to the vaudeville theaters. Actuality film — reenactments of media events and the forerunners of newsreels — proved to be very popular with the new audiences.

The first nickelodeon was built in Pittsburgh in June 1905, and others quickly flourished around the country. By 1908, approximately 8,000 nickelodeons in the U.S. allowed people to stop in almost anytime to enjoy the frequent showings. Later, bigger theaters would be built allowing larger audiences to see longer films projected on a bigger screens.

Media Moments

1900 – Thomas Edison’s execution movie of McKinley’s assassin. An actuality – a short non-fiction film – of the execution of the assassin of McKinley carried out from the description of an eyewitness. Motion pictures became popular, first as single-viewer kinetoscopes, then as films projected for mass audiences. Edison’s company, Thomas A. Edison, Inc., produced films showing famous people, news events, disasters, and everyday people doing everyday activities.

1901 – Guglielmo Marconi, the “father of radio”, took a simple interest in “Hertzian Waves” and invented one of the most important new media’s of the new century. Having first experimented with radio transmissions in the attic of his parent’s home, Marconi traveled to England in a search for investors. There, he founded the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company Limited which began building radio equipment in 1889. To publicize the new invention, Marconi gave numerous demonstration, including one to Queen Victoria. In 1901, Marconi successfully transmitted the first radio signals across the Atlantic Ocean.

1903 – One of Edison’s most famous ‘actualities’, this action film depicted a robbery by Butch Cassidy. Enormously popular, it is one of the first films to tell a coherent story. Later, when the audiences became bored with “real” events, Edison and his company began producing action, drama and comedic films.

April 18, 1906 – San Francisco’s devastation captured on film. Only days after and earthquake and fire destroyed much of San Francisco, the first “newsreels” were there to capture the devastation. This disaster would be the first major event of its kind to be captured for the viewing audiences around the United States and the world, though much the “ongoing destruction” was staged for the cameras.

1907 – First trial of the century. Girl meets boy: Evelyn Nesbit, a 16-year-old showgirl, enjoyed some, but not all of the affections of Standford White, the famous New York architect who designed Madison Square Garden. Boy meets girl: Henry K. Thaw, an “eccentric” millionaire met and eventually married Evelyn, but grew to hate her former seducer, White. Boy flies into a jealous rage and kills wife’s ex-lover: Thaw shot White as he entertained on the roof garden of Madison Square Garden and was immediately arrested. Press has field day: supposedly even President Theodore Roosevelt followed the coverage in the newspapers. Justice served?: Thaw was eventually freed and immediately divorced Evelyn.

1908 – Electric light. Thomas Edison — having already conceived, built and marketed an amazing number of devices like the motion picture camera — invents the electric light. Now taken for granted, the electric light changes society. It became much easier for people to to stay up late in the evening and enjoy more social activities. The night was somewhat tamed by the spread of street lamps, headlights and illuminated signs. The stars disappear in urban areas, and life becomes a 24-hour experience with the simple flick of a switch.

Trends in Journalism

The era before and during the 1900s is known as the age of yellow journalism, when sensational headlines and lurid stories were the norm. It was also a time when many determined journalists exposed corruption in government, the unfair treatment of factory workers, and the privileges of the upper class.

McClure’s Magazine, owned by Samuel McClure and originally established as a general interest magazine, moved into the business of muckraking, exposing the faults of expansion and industrialization. These two trends — yellow journalism and muckraking — helped newspapers and magazines become the dominant form of mass media.

Newspaper publishers Hearst of The New York Journal and Pulitzer of The New York World were in a circulation war fighting for the same new target audience – immigrants, who were still pouring in to the New World from Europe. One of the most memorable stories from the era, the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine, would help to propel the United States to war with Spain.

Advertising grew and promoted a culture of consumption. Magazines such as Call’s Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post took advantage of advertising to increase their circulation and still keep subscription prices low.

General interest and ladies magazines also flourished. Magazines such as Good Housekeeping and Vogue began targeting niche markets: homemakers and fashion-oriented women. Between 1890 and 1905 the circulation of monthly periodicals went from 18 million to 64 million.

The 1910s

Overview

The Muckrakers of the 1900s gave way to investigative reporting and war correspondents in the 1910s. Political and social pressures helped form the decade with the four-way presidential election of 1912, the release of the film “Birth of a Nation,” and World War I all helping to divide the American public.

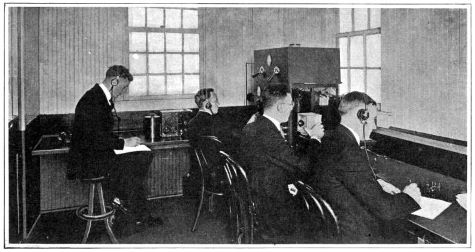

Newspapers were a source of activism for political parties and for social equality. Radio was beginning to make an impact on society and journalism, and the 1910s would lay the groundwork for the rise of radio in the 1920s.

Journalists and Media Personalities

Carr Van Anda was an editor at the New York Times when the Titanic struck an iceberg on Sunday April 14, 1912. The next morning, the Times was the only newspaper to report that the Titanic had indeed sunk — other newspapers having simply reported that the ship had been damaged. When the survivors returned to New York, Van Anda organized the coverage by renting one floor of a local hotel and installing an unprecedented four phone lines. Van Anda reinvented the way the media covered disasters.

William Monroe Trotter was born April 7, 1872, and raised in the wealthy Hyde Park suburb of Boston. He was the only African American in his high school, but was elected class president and graduated as the valedictorian. After college at Harvard, Trotter founded the activist newspaper The Boston Guardian. The paper was “propaganda against discrimination,” and fought for equal rights for blacks. Trotter’s paper frequently railed against Woodrow Wilson because the president had segregated some public offices. Trotter led a delegation to the White House 1914, where he debated Wilson until he was thrown out. William Monroe Trotter is remembered as an early civil rights activist and the founder of an African American newspaper.

Richard Harding Davis was the first modern war correspondent. By the age of 26 he had become the managing editor of Harper’s Weekly, but left to cover the Spanish War. He then went to Cuba to cover the Spanish-American War, then the Greco-Turkish War, and then the Boer War in Africa. By the time World War I began in Europe, Davis had become such a respected war correspondent that he was paid $32,000 a year to report on it. He was captured by the Germans in 1914 and accused of being a British spy, but was released soon after they found he was an American. He covered the war until 1915, when he left because he disagreed with the Allied restrictions on the press.

Henrietta “Peggy” Deuell, a Kansas farm girl, left home at an early age to become a journalist. After her marriage to a fellow journalist, Peggy Hull covered General Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa in Mexico, and survived submarine-infested waters to report from the Western Front during World War I — without any official recognition or assistance from the United States government, which frowned on the idea of female war correspondents. With help from General Perusing, Hull became the first officially accredited female war correspondent and promptly accompanied American soldiers to Siberia during the Russian revolution. In Shanghai during the Japanese invasion of the city, Hull stayed to cover the action, and would continue coving the war in the Pacific after the United States entered the Second World War. She was known for featuring the “ordinary” man in her stories. In 1944, an American G. I. wrote to her, saying “You will never realize what those yarns of yours . . . did to this gang. . . . You made them know they weren’t forgotten.”

Floyd Gibbons, a war correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, was aboard the troop transport, S.S. Laconia, when it was sunk by a German U-boat. Later, he was wounded in the trench warfare in Europe. Having been hit by three bullets, the grievously wounded Gibbons waited hours for the sun to set before he could retreat from where he was pinned down by enemy fire.

Depressed by the carnage on the Western Front, Lloyd Thomas a war correspondent with an interest in the new art of documentary filmmaking, traveled with his cameraman to the Middle East in search of a story. He found and filmed T. E. Lawrence, an eccentric British officer leading a revolt of the Arabs against the Ottoman Empire. Thomas joined a traveling show with his documentary film With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia. The success the film made Thomas famous as an adventuring journalist, and made “Lawrence of Arabia” a legend. Thomas would have a long career as a radio newscaster and narrator of newsreels. He also appeared on the first television news broadcast in 1939. He would retire from journalism in 1976, after almost 60 years in the business.

Benito Mussolini broke from Socialism in 1914 when he founded a paper called “The Italian People.” He also started a pro-war group and coined the term “fascism” from a symbol of Roman power. After being wounded by a grenade in 1917, he returned to edit his paper until he was elected to the Italian parliament in 1921. His skills as a journalist would help him win election to head the Italian government, and he would prove to be a popular international figure until the 1930s.

George Creel began his newspaper career at the Kansas City World, then started the Kansas City Independent. He was chosen by Wilson to head the Committee for Public Information in 1917, which was responsible for raising American support for the war effort. He organized poster campaigns, music tours, speaking engagements and cartoons to galvanize American sentiment. He also organized a campaign in America and Europe to raise support for Wilson’s Fourteen Points and he is credited in part with the acceptance of the plan.

Political Scene

1910-1919 was a decade of unrest throughout the world. In America, the decade began with a contentious election between the Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Republican Taft, Progressive Roosevelt, and the Socialist Eugene Debs. With Republican voters split between Taft and Roosevelt, Wilson won 42 percent of the popular vote and 82 percent of the electoral college.

The outcome might have been different if the Roosevelt camp leaked an letter taken from Wilson’s luggage that would have disclosed an affair between Wilson and Mary Peck.

After the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in 1914, a web of allegiances pulled Europe into war. The isolationist United States entered the war in 1917 as U.S. pressures against Germany grew with revelations that they had fermented unrest against the U.S. in Mexico.

The Treaty of Versailles ended the war in 1919, but the Allied leaders, Lloyd George of England, Vittorio Orlando of Italy, and Georges Clemenceau of France, forced unreasonable restrictions on Germany. Wilson’s Fourteen Points were a starting point, and the League of Nations was established, but the U.S. Congress was dissatisfied with the arrangement and never allowed the U.S. to join the League.

In Russia, the Bolsheviks led by Lenin seized control of the countr and the United States was worried that a revolution might be incited here as well. Legislation that was eventually ruled unconstitutional restricted Americans’ speech. Eugene Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison under the Sedition Act of 1918, and Emma Goldman deported in 1919 under the California Criminal Syndicalism Act.”

Social Climate

In July of 1914, a Serbian terrorist shot and killed Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austria-Hungary throne, while he visited the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia. Thanks to a web of confusing alliances and agreements between the various European powers, the continent descended into war. Austria marches on Serbs; the Serbians call on their ally Russia; the German Kaiser unsuccessfully urged his cousin, the Russian czar, not to intercede; the Germans came to the defense of Austria; once attacked, Russia drew in France; the Germans marched into France through Belgium — which was neutral, thus bringing England, Italy, The Ottoman Empire and — eventually — the United States to enter the war.

World War I produced new technologies that killed soldiers more effectively than had ever been seen. The use of poison gases, heavy artillery, machine guns, tanks, blimps and airplanes contributed to a stalemate that dragged the battles into muddy trench warfare with forces separated by a no-man’s land.

Socialism became a political force in American politics. Eugene V. Debs ran for president in 1912, his forth attempt, while Victor Berger, a Socialist newspaper owner from Wisconsin, was elected to U.S. Senate. Both men were punished under new laws that condemned political dissent.

Berger’s most influential newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader, established in 1911, became the vehicle for his vocal opposition to World War I. Berger’s views on World War I were complicated by the socialist view and the difficulties around his Germanic heritage. However, he did support his party’s stance against the war.

When the United States entered the war and passed the Espionage Act in 1917, Berger’s continued opposition made him a target: He and four other Socialists were indicted under the Espionage Act in February 1918. Berger was eventually sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. Berger appealed and his sentence was ultimately overturned on a technicality on January 31, 1921, by the Supreme Court, three years after the end of the First World War.

In spite of his being under indictment at the time, the people of Milwaukee elected Berger to the House of Representatives in 1918. When Berger arrived in Washington to claim his seat, Congress formed a special committee to determine whether a convicted felon and war opponent should be seated as a member of Congress. On November 10, 1919, they concluded that he should not, and declared the seat vacant. Wisconsin promptly held a special election to fill the vacant seat and on December 19 elected Berger a second time. On January 10, 1920, the House again refused to seat him and the seat remained vacant until 1921, when Republican William H. Stafford claimed the seat after defeating Berger in the 1920 general election.

Media Moments

1914 – D. W. Griffith’s film, Birth of a Nation based on the Thomas Dixon novel The Clansman was a huge success and put Griffith at the top of the film industry. Called a racist and picketed by black leaders such as William Monroe Trotter, Griffith released Intolerance as a counterpoint, but to much less acclaim. The most popular film of its time, Birth of a Nation would ultimately ruin Griffith’s career.

April 15, 1912: The Titanic sinks – At 1:20 a.m. on April 15, a Marconi wireless station in New Foundland picks up an SOS from the R.M.S. Titanic. Carr Van Anda of the New York Times calls to find that the Titanic’s wireless was silent half hour after the distress call was received. Before 3:30 a.m. Van Anda and staff organize the story, retrieving a passenger list and pictures of the Titanic. Reports of icebergs were received from ships in the area where the Titanic last transmitted. The following morning the New York Times led with the story that the Titanic had sunk, while other papers report inconclusive news.

When ships carrying rescued passengers arrived, Van Anda rented out a floor in a hotel a block from where R.M.S. Carpathia would dock with survivors and install four telephone lines direct to New York Times offices. Van Anda persuaded Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of wireless, to interview the Titanic’s wireless operator on board the Carpathia and scored another scoop with the last messages of Titanic.

June 28, 1919: Peace treaty ends First World War, sets stage for second – The Treaty of Versailles, signed in Paris, ended the First World War. Woodrow Wilson presented his Fourteen Points to keep the world safe for democracy, but other Allied leaders wished to punish Germany. At left, Lloyd George of England, Orlando Vittorio of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France and U.S. president Woodrow Wilson in Paris were negotiating the treaty that would breed resentment in Germany, leading to the rise of Adolf Hitler and World War II.

Trends in Journalism

During the 1910s, American’s interest in muckraking journalism waned and publishers shifted focus as their audience’s tastes changed. Magazines like Vanity Fair, The Smart Set and Vogue focused on the lifestyles of the rich, while the squalid lives of the underclass became the staple of tabloid newspapers and confessional magazines.

New technologies also made the 1910s important. The Radio Act of 1912 marked the first time Congress attempted to regulate the new technology, also known as the wireless telegraph. The act put radio waves in control of government, which divided the bandwidths up for different uses. Each broadcaster was assigned a three- or four-letter codes and all ships were required to carry wireless radio equipment, due in part to the Titanic disaster in April of 1912. The use of radio would expand during the 1910s, especially after wartime advances funded by the United States military filtered down into commercial use in the media industry.

With the start of the First World War, modern war journalism was born upon the battlefields of Europe and the Middle East, and nurtured by journalists like Richard Harding Davis, Floyd Gibbons, Peggy Hull and Lowell Thomas. Hundreds of American journalists provided unprecedented and unmatched coverage of the war. Back on the home front, modern propaganda in America was born when President Woodrow Wilson created the Committee of Public Information, headed by George Creel, to help manage the flow of news and information to the American populace.

Movies became increasingly popular with the public, but many serious actors refused to work in the new medium. One of the early silent film stars and a beloved actor of the early century was Charlie Chaplin. His first big-studio picture came out in 1914, which he starred in and directed. Chaplin was also known to write the accompanying music for his silent films. Other stars of the first age of film include Rudolf Valentino, Lillian Gish, Buster Keaton, Lon Chaney, Mary Pickford and Fatty Arbuckle.

D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation would prove to be the most popular and most controversial film of the decade. Highlighting the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, Griffith’s reputation would be stained by his most “successful” film. Lillian Gish called him “the father of film” and Charlie Chaplin called him “the teacher of us all.”

Newsreels, still in their childhood as a new medium, would continue to mature. Woodrow Wilson, during the twilight of his presidency, spent many hours watching newsreels of himself during the happier moments of his administration.

The 1920s

Overview

Profound cultural and social conflict marked the years of the 1920s. New cultural attitudes towards race, immigration and evolution, along with changes in the social fabric, pitted the new cosmopolitan culture against more traditional and conservative ideals. Social changes included the rise of consumer culture and mass entertainment in the form of radio and movies. The changing of sexual mores and gender roles marked a sharp separation from the Victorian past. Prohibition made alcohol illegal, while wild speculation in the stock market, along with unhealthy corporate structures, ensured the decade’s relative prosperity would end in a Great Crash.

Jazz and tabloid journalism charted a new era of sensationalism focusing on sex and crime. While the victorious nations from the First World War enjoyed the spoils, resentment bred in Germany, setting the stage for future conflict.

In his 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Journalists and Media Personalities

The creator of the National Broadcasting Company who helped develop television. Sarnoff became the most powerful figure in the communications and media industries. He claimed to have scooped the world on the Titanic disaster, staying at his telegraph key for 72 hours. In 1915, he submitted a memo to the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, which granted him $2,000 to develop his idea for a “radio music box.” By 1924, the box had sold $83 million worth of units. Sarnoff’s chief ambition wasn’t making money but enlarging the applications of the electronic media through research and development.

Radio tycoon who headed the Columbia Broadcasting System. Paley was regarded as a programming genius who rewrote the nation’s definition of entertainment and news. In 1928 he bought $50 worth of advertising on Philadelphia station WCAU for his father’s company, La Palina Cigars. Sales skyrocketed and the family ended up buying a chain of stations, which Paley renamed the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). He became president of the network on September 28. He set up his own news organization and recruited a veritable dean’s list of newsmen: Edward R. Murrow, William Shirer and Eric Sevareid, just to name a few.

Henry Luce, along with Briton Hadden, launched Time magazine in 1923. The magazine developed innovative approaches to news coverage, including packaging the news in topical units and replacing standard newspaper prose with a catchy narrative style. From the start, Time was accused of bias; Luce and Hadden were conservatives who opposed government interference of business. After Hadden died in 1929, Luce went on to build a media empire that included Fortune, Life, Sports Illustrated and Time-Life books.

A Kansas editorial writer and newspaper owner who walked among the giants of politics, White worked fervently for the causes he believed in. White even left his newspaper, The Emporia Gazette, to run independently for governor when the two main candidates accepted endorsements from the Ku Klux Klan. White won a Pulitzer Prize in 1922 for his editorial To an Anxious Friend”, defending free expression.

“You tell me that law is above freedom of utterance. And I reply that you can have no wise laws nor free entertainment of wise laws unless there is free expression of the wisdom of the people – and, alas, their folly with it. But if there is freedom, folly will die of its own poison, and the wisdom will survive.”

William Allen White, “To an Anxious Friend”, July 27, 1922

The stars of America’s most popular radio show, Amos ‘n’ Andy. The white men did schtick based on stereotypical black men. In an era of blackface entertainment, there were no protests. The show broadcast six nights a week in 15-minute installments. So popular was the show, that America would stop from 7:00 to 7:15, movie theaters would shut off their projectors and roll out radio sets. The show retained its popularity through the 1940s.

The comedian and social critic rose to radio stardom in 1922. He was famous for saying, “I never met a man I didn’t like.” Rogers regarded Congress as his “joke factory.” He became a syndicated writer whose columns appeared in more than 400 newspapers. His homespun wit made him a beloved national figure. At the 1932 Democratic National Convention, Rogers fell asleep only to wake up to find he’d been nominated for President. “If elected, I promise to resign,” he said. He died in a plane crash in 1935.

The Johnsons traveled the globe photographing and filming their adventures in Africa, the South Pacific and elsewhere. In order to finance their trips, the Johnsons signed contracts to advertise tobacco, soft drinks, cosmetics and coffee. Their films proved extremely popular and, for a time, Osa Johnson’s popularity matched that of Eleanor Roosevelt or Ann Lindbergh.

Health guru who earned his fortune from the magazine Physical Culture. Macfadden introduced the confession magazine in 1919 with True Story, which had a weekly circulation of more than 2 million. Its success was attributed largely to its sexual frankness. True Story addressed sexual problems in a clinical rather than erotic way. Realizing that the word “true” sold copies, Macfadden launched the first quasi-factual detective magazine, True Detective Mysteries, in 1924. Macfadden’s magazines were profitable and innovative, but his newspapers, including the tabloid the New York Evening Graphic, failed.

The most widely read columnist in American journalism. His “three-dot” column was a must-read in the New York Evening Graphic and, later, in the New York Daily Mirror. Once he said about celebrity: “To become famous, throw a brick at someone who is famous.” The content of his columns broadened through time, starting with show-biz gossip and expanding to include items about politics and business. His writings spawned a journalistic genre. Winchell’s greatest media exposure came from his weekly radio broadcasts, which began in 1930 with the greeting: “Good evening, Mr. And Mrs. America and all the ships at sea.” After World War II, he was denounced as a fascist by the left for his strong stance against communism.

Originally from North Carolina, “Doctor” Brinkley, a con man with a dubious medical education, claimed he could restore male virility by implanting goat glands from his clinic in Milford, Kansas. Brinkley then opened KFKB, one the of first radio stations in the country. Unburdened by federal limitations on signal strength, Brinkley’s high-powered station sold his pharmaceuticals and spread his politics nationwide. After an unsuccessful write-in campaign for the governorship of Kansas, Brinkley would move his operation to Mexico.

Following a successful baseball career, Billy Sunday traded his uniform for a preacher’s collar, becoming one of the most successful evangelical ministers of the early decades of the 20th century. Preaching conservative christian ideals, Sunday played a crucial role in the Prohibition movement. He would also inspire future evangelical ministers with his charismatic — and athletic — preaching style, as well as his use of radio to spread his message.

Political Scene

With the end of World War I came deep-seated fears of political radicalism, the beginnings of what would become the “Red Scare.” Before the end of the Wilson presidency, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer led raids on leftist organizations such as the International Workers of the World, a labor union. Palmer hoped his crusade against radicalism would usher him into the presidency. He created the precursor to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which collected the names of thousands of suspected Communists.

More than 500 aliens on the list were deported, including the radical orator Emma Goldman. Palmer claimed he was ridding the country of “moral perverts,” but his tactics, which tended to violate civil liberties, proved to be too draconian in the minds of the electorate.

During the early 1920s, the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan swelled to 4.5 million. The Klan helped to elect 16 U.S. Senators, as well as many Representatives and local officials. When David Curtis Stephenson, Indiana’s head Klansman, was convicted of kidnapping and sexual assault in 1925, indictments and prosecutions of Klan-supported politicians on corruption charges followed. Nationwide membership of the Klan fell to just 45,000 in five years.

Marcus Garvey, the “Black Moses,” led a national movement whose theme was the impossibility of equal rights in white America. Garvey preached black pride, segregation and a return to Africa, but the decade’s currents of white supremacy overpowered him. He was charged with mail fraud, jailed and deported.

William Allen White, a small-town editor in Emporia, Kansas, crusaded against the Klan and for free speech. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial, he wrote: “If there is freedom, folly will die of its own poison.”

With the passage of the 19th Amendment, women were given the right to vote in 1920, but voting remained an upper- and middle-class activity. No new opportunities in the workplace arose, and the momentum of the women’s movement at the beginning of the decade was eventually swallowed by the rise of consumer culture.

Warren G. Harding, a Republican Senator from Ohio, was elected President in 1920. Under Harding, government’s previous efforts to regulate business practices were relaxed in favor of a new emphasis on corporate partnerships. Best known for a series of outrageously corrupt political scandals, Harding’s presidency was not without its merits. He pardoned Eugene Debs, the imprisoned Socialist Party leader; he persuaded the steel industry to enact an 8-hour workday; and he helped slow down the arms race. However, his administration was stacked with corrupt officials who gave kickbacks to the Justice Department and the Veterans Bureau. After Harding died of a stroke while still in office in 1923, the Teapot Dome scandal broke, revealed that private oil companies had been draining oil from federal lands.

Harding’s sudden demise meant his Vice President, Calvin Coolidge, held the top office. Nicknamed “Silent Cal,” Coolidge was asked during the 1924 election if he had anything to say about the world situation. His reply: “No.” Still, a divisive Democratic Party helped the incumbent win the election by 7 million votes.

When the Democrats nominated Al Smith, an Irish-Catholic from New York’s Lower East Side, for President in 1928, the party closed ranks behind him, but economic prosperity and anti-Catholic sentiment kept Smith from being elected. He is credited with awakening a vast army of immigrants in the big cities and with shifting African-American voters toward the Democrats.

The 1928 President-elect, Herbert Hoover, envisioned a private economy that would operate mostly free from government intervention. Predicting ever-greater prosperity, he said, “We shall soon, with the help of God, be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.” But then the stock market fell out from under him.

Social Climate

The image of the 1920s as a decade of prosperity, of flappers and hot jazz, is largely a myth, even in the eyes of the writer who coined some of those terms. In his article “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “It was borrowed time anyway – the whole upper tenth of a nation living with the insouciance of a grand duc and the casualness of chorus girls.”

There is some truth to the decade’s image of prosperity but, as Fitzgerald notes, it was concentrated at the top. Six million families made less than $1,000 a year. According to the Brookings Institution, one-tenth of 1 percent of families at the top took in as much income as 42 percent of families at the bottom. In New York City, millions of people lived in tenements condemned as firetraps. When Fiorello La Guardia, a Congressman from East Harlem, toured the poorer districts of New York in 1928, he reported: “I confess I was not prepared for what I actually saw. It seemed almost incredible that such conditions of poverty could really exist.”

Labor strikes broke out, pitting coal miners and railroad men against their powerful employers. Burton Wheeler, a Senator from Montana, visited one of the strike areas: “All day long I have listened to heartrending stories of women evicted from their homes by the coal companies. I heard pitiful pleas of little children crying for bread. I stood aghast as I heard most amazing stories from men brutally beaten by private policemen.”

There was a sweeping crackdown on immigration. New quotas were established that heavily favored Anglo-Saxons. China, Bulgaria, Palestine and the African nations could send no more than 100 people. England and Northern Ireland could send 34,000, while Italy could send just under 4,000.

Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis were part of a generation of writers, artists and musicians who were among the most innovative in the country’s history. Traditional taboos concerning sex and gender politics were challenged. The country went dry on January 16, 1920, after Prohibition was successfully linked with Progressive Era causes, such as reforms to end wife beating and child abuse.

The 1920s also saw a rise in tension between whites and blacks. In May of 1921, a large section of Tulsa was burned to the ground and a number of blacks and whites were killed. Some of the worst racial violence in American history took place during the 1920s. On the first day of 1923, a white mob searching for an alleged rapist burned all but one building in the tiny black settlement of Rosewood, Florida. Millions of blacks moved to northern cities. Soon, the black population of Chicago had swelled by 148 percent, Detroit’s by 611 percent. Many cities adopted residential segregation ordinances to keep blacks out of white neighborhoods.

The United States became a consumer society in the 1920s. The automobile was its symbol; by 1929, there were 27 million autos on America’s roads. Cigarettes, cosmetics and synthetic fabrics became staples of life. The rise of radio and the talking motion pictures (90 million Americans were going to them weekly) helped create a new popular culture that disseminated common speech, dress and behavior.

Media Moments

1920 — KDKA, the first official radio station: Frank Conrad of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, first started experimenting with the recently invented medium of radio in 1912. At the time, the technology primarily functioned as a means of naval communications; a lesson learned from the sinking of the Titanic. As the public began purchased amateur radios, Conrad’s broadcasts became popular. Conrad is credited with inventing radio advertising when he started mentioning the name of the store giving him new records to play on the air. Westinghouse Electric Company, Conrad’s employer, recognized the potential of his hobby and began manufacturing and selling more radio receivers. On October 27, 1920, Westinghouse received the first formal license from the federal government to broadcast as a terrestrial radio station. Designate KDKA, the station gained instant success when it broadcast live results of the 1928 presidential election.The call letters, KDKA, carry no significance, and would have been awarded to a naval station had Westinghouse and Conrad not discovered a new use for the technology.

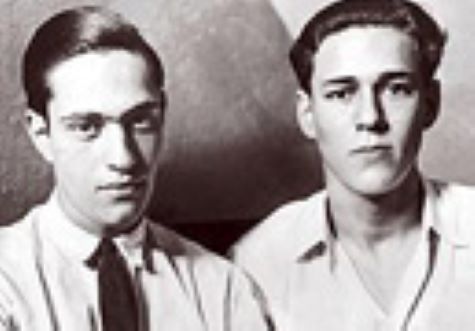

1924 — Leopold and Loeb: Another “trial of the century.” The two teenagers from highly privileged Chicago families, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, kidnapped, killed and mutilated a 14-year-old neighbor. The case challenged previously held notions of juvenile killers with below-average IQs. Leopold would describe the pair as evil geniuses who were above normal standards of morality. Their attorney, Clarence Darrow, introduced the psychiatric defense into the legal system. The jury and the press accepted Darrow’s argument that society, schools and violent social conditions were to blame, and the killers avoided execution.

1925 — Scopes Monkey Trial: Fundamentalist-christians introduced 37 anti-evolution bills to 20 state legislatures during the 1920s, and the first one to pass was in Tennessee. Taking up the ACLU’s offer to defend anyone who violated the new law, Dayton, Tennessee, booster George Rappleyea realized the town would get all kinds of publicity if a local teacher was arrested for teaching evolution. He enlisted John Scopes, a science teacher and football coach. The trial was marked by a carnival-like atmosphere; for 12 days, 100 reporters sent dispatches from Dayton. Scopes’ $100 fine was later thrown out on a technicality. It went down in history and literature as one of America’s best-known trials and symbolized the conflict between faith and reason.

May 21, 1927 — Lindbergh’s flight: 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight in history in “The Spirit of St. Louis.” The trip was 3,610 miles, beginning from Roosevelt Field on Long Island and ending in Paris after 33 hours and 30 minutes. The aftermath was what came to be known as the “Lindbergh boom” in aviation: industry stocks rose and interest in flying skyrocketed. Lindbergh’s subsequent U.S. tour demonstrated the potential of the plane as a safe and reliable mode of transportation.

1928 — Ruth Snyder Executed: Ruth Snyder, a discontented Long Island housewife, convinced her lover, Judd Gray, that her husband was mistreating her. The pair killed him with a sash weight. Their trial was a media frenzy, attended by such celebrities as film pioneer D.W. Griffith and evangelist Billy Sunday. The jury was out 98 minutes before it returned with a guilty verdict. Gray was executed first on January 12, 1928. Snyder followed just a few minutes later. A clever photographer from the New York Daily News, with a camera strapped to his ankle, snapped a picture of her as the juice coursed through her body. It sold 250,000 extra copies and is the iconic image of the 1920s.

October 29, 1929 — The Stock Market crashes: Heavy speculation on in stocks cause a bubble which burst in October. Fortunes were lost almost instantly. Breadlines filled with the unemployed and the homeless become commonplace. This unprecedented downturn in the economy would cause stagnation and strife around the world. The Roaring Twenties come to screeching halt and the Great Depression settled in, dominating the 1930s.

Trends in Journalism

The shift from print-based journalism to electronic media began in the 1920s. Competition between newspapers and radio was minimal, because the latter was not yet an effective news medium. People listened to radio bulletins, but to “read all about it” they picked up a tabloid or a broadsheet.

The New York World was generally known as the best paper of the decade. Regarded as “the newspaperman’s newspaper,” it was, in stature, the New York Times of its day, relying on solid reporting and writing instead of broad coverage. The paper’s lauded and independently liberal editorial page was edited by Walter Lippmann, who became one of the most influential American writers of the century. The paper’s merger into the World-Telegram is seen as a black day in newspaper history.

The talkie newsreel was born when Theodore Case developed his sound-on-film system. The Fox Film Corporation bought Case’s system in 1926 and developed Fox Movietone News. The first talkie newsreel showed Charles Lindbergh taking off on his transatlantic flight on May 20, 1927. Its enormous success compelled other studios to produce competing newsreels. They became so popular that theaters showing only newsreels opened in major cities around the country.

Radios were first marketed for home use in 1920. By 1929, they sold 5 million sets every year. RCA’s Radiola was the most widely advertised model, selling for $35. RCA formed the National Broadcasting Company, which had its first broadcast on November 15, 1926. Programming remained unimaginative until the end of the decade, relying on speeches, lectures (on such topics as basket weaving) and music. In 1925, more than 70 percent of air time was devoted to music; less than 1 percent was devoted to news. By 1929, 40 percent of the population owned radios, tuning in to hear music, sports scores, Al Jolson (the decade’s top star) and Amos ‘n’ Andy.

Jazz journalism brought with it sensational stories printed in a popular tabloid format. Modern media’s obsession with sex and crime has nothing on the era’s scandalous content. Stories such as the 1922 Hall-Mills case (involving the murder of a minister and a choir singer) and the 1927 Snyder-Gray case (involving the murder of a husband by an adulterous wife) gripped the nation. Competing tabloids included Joseph Medill Patterson’s The New York Daily News, William Randolph Hearst’s The New York Daily Mirror, and Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic, also known as the “Porno-Graphic.”

Modern advertising took root in the 1920s when advertising agencies started to take shape.

The 1930s

Overview

The Great Depression dominated the 1930s. The despair of the poor and unemployed eventually turned to hope as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt initiated the New Deal, an “alphabet soup” of programs designed to boost the economy through public works programs and other federal intervention. The failed experiment of Prohibition would end in 1934.

Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party came to power in Germany; Benito Mussolini’s Fascists expanded Italy’s empire, and Francisco Franco’s Falangists brought their own version of fascism to Spain. Before the decade ended, Europe would descend into war for the second time in the century. The United States claimed neutrality, but supported the British.

The 1930s has been called the “Age of the Columnists.” The form of the signed, regular editorial spot for writers on social and cultural issues of the day included everyone from comedians to First Ladies. It was also the decade which saw the rise of 35mm photography and photojournalism, and the heyday of newsreels. Radio journalism became the dominant elecronic medium for news and entertainment, while the newly invented television technology would have to wait until for another decade before it’s potential could be realized,

Journalists and Media Personalities

Widely respected editor of The New Republic, an independent liberal journal of opinion, which relied on donations and grants instead of advertising for revenue. Lippman helped President Woodrow Wilson draft his Fourteen Points, though he would later argue against the League of Nations and the Allies’ postwar demands. In the 1930s, Lippman began his nationally syndicated column, “Today and Tomorrow”, which would remain popular with readers for the next 30 years.

Murrow’s long and influential career in broadcasting started with a radio report from Vienna when Adolf Hitler’s Germany annexed Austria. He would go on to gather the most illustrious team of broadcast journalists the next decade saw, and continue to be an important journalistic voice into the early 1960s.

Kaltenborn began his career in radio with CBS in the 1930s, making a name for himself with broadcasts from the front during the Spanish Civil War. He gained greater fame for covering the Munich Crisis when Germany, England and France negotiated the fate of Czechoslovakia in 1938. During this time, he worked closely with Edward R. Murrow; but in 1940, Kaltenborn would move to NBC. His career in radio would continue into the 1950s, despite garnering the ire of a victorious Truman following the 1948 presidential election. Truman mocked the radio man’s premature projection of a Dewey victory, but Kaltenborn laughed, saying “we can all be human with Truman. Beware of that man in power who has no sense of humor.”

Winchell began his career covering Broadway as a gossip columnist in New York city. In the 1930s, Winchell moved to the growing medium of radio, expanding his coverage to political gossip. An early critic of both Adolf Hitler and Communism, Winchell would be a staple of both radio and print until the 1950s. Though Winchell would enjoy a lucrative paycheck as narrator for the television show The Untouchables, it would be Winchell’s support of Joseph McCarthy that ended his success as a columnist and radio personality.

“‘Good Morning, Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea.”

Winchell radio show greeting

Luce began publishing Time, the first weekly news magazine, in 1923. In 1930, he introduced the prototypical business magazine, Fortune. In 1936 Luce pioneered the photojournalism magazine genre with Life. His empire also included radio and newsreel journalism with the March of Time series.

Documentary photographer who depicted the plight of Dust Bowl migrants in California for the Federal Emergency Relief Agency. Later for the Farm Service Administration, she photographed the depopulated Great Plains and the lives of rural Americans throughout the Southern and Midwestern United States.

Bourke-White’s photo of a TVA dam project would be used as the first cover of Life magazine. She was the first woman war photographer, the first woman to fly on a combat mission, as well as the first American to document in pictures the lives and industry of Soviet Union.

A leading magazine reporter of her day, she covered the Spanish Civil War as well as World War II as a “literary journalist.” She wrote several novels, met Ernest Hemingway while in Spain, married him, then left him to cover World War II.

Coughlin, a Catholic priest with a charismatic preaching style, became a popular radio personality during the late 1920s and 1930s. Originally a supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Coughlin broke with the president in 1934, believing that FDR had moved too far to the left. An ardent anti-communist, Coughlin applauded Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini for their tough stand against communists and Jews. Following the United States entry into the war, Coughlin disappeared from the media stage.

A charismatic politician, Huey Long became governor — some would say dictator — of Louisiana in the late 1920s and would eventually run for president during the 1936 election cycle. Long owned newspapers and used radio to build support for his populist viewpoints. Huey Long seemed to thrive on controversy, and his progressive ideas proved too radical for some. On September 10, 1935, Long died of wounds suffered at the hands of a lone gunman.

Political Scene

In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover in a landslide election for the U.S. presidency, due mainly to the nation’s struggles of the Great Depression. Many of the voters blamed Hoover and “Hoovervilles” became a common nickname for the migrant shantytowns popping up around the country.

Following his inauguration, Roosevelt immediately introduced legislation for a wide range of liberal reforms — collectively known as the New Deal — intended to stimulate the economy. These programs, along with Roosevelt’s deft media manipulation, would help him win the presidency four times, the only person to win more than two. He achieved this feat despite the fact that he had suffered from polio as a child and did not have the use of his legs — a fact that the media kept secret from the public.

In Germany, a political maelstrom was brewing. By the early 1930s, the president and other U.S. officials had learned of Hitler’s power and domination in Europe. Under Hitler, the Nazi regime stripped away the rights of Jews and other citizens, killed the innocent, sterilized people with genetic defects and vied for German world domination. Leni Riefenstahl, German actress-turned-director, captured the 1934 Nazi rally in Nuremberg and the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, among others.

In Italy, Mussolini continued in power, eventually becoming absolute ruler of a fascist state. His armies would eventually invade the African nation of Ethiopia. His interest in media continued to flourish, though he was chiefly concerned with controlling the message and censoring dissent.

Social Climate

The stock market crashed on October 24, 1929, initiating the Great Depression. By 1933, corporate profits sank to one-tenth of their 1929 levels, the gross national product declined by 50 percent. and 13 million unemployed men and woman — one in four workers — struggled to make ends meet. Social unrest grew among the populace, culminating in marches by unemployed veterans of World War I demanding assistance from the federal government. They were met with tear gas and riot batons.

Roosevelt’s New Deal created government projects that employed people to build roads and dams, in the hopes of stimulating the economy. The Dust Bowl drought eroded nine million acres of Midwestern farmland, driving hundreds of thousands of farmers to abandon their land and head west for California. John Steinbeck depicted this exodus in his masterpiece novel The Grapes of Wrath.

Due to the state of the economy, union membership increased dramatically, and communism attracted many who saw big business greed as responsible for the Depression. Many of these people would come to regret such affiliations in the McCarthy era of the 1950s.

Amos ‘n’ Andy, by far the most popular radio program, relied on two white men imitating (and helping to define) a stereotype of African-Americans for its humor.

In Hollywood, Busby Berkeley produced several spectacular, fabulously choreographed musicals, with innovative cinematography and lavish sets and costumes. Frank Capra spoke to a dispirited nation with movies like American Madness. In 1938, the Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, both directed by Victor Fleming, were released.

Mexican border radio stations featured hillbilly music shows, which introduced to the country such influential artists as the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. Woody Guthrie moved to New York, bringing his songs of “Okie” travails and social protest to the city. Important blues musicians such as Robert Johnson, Charlie Patton and Son House cut several records and toured mostly in the South.

Media Moments

1930s — FDR’s Fireside Chats: Roosevelt used the media as well as any media-savvy president of the 20th century. His most important innovation in communicating with the American public was his weekly radio broadcast. Known as “Fireside Chats,” these radio speeches and his warm, earnest speaking style reassured a citizenry jittery over the wrecked economy and the future of the country, and won the public over to his New Deal agenda.

1936 to 1939 — The Spanish Civil War: Roosevelt used the media as well as any media-savvy president of the 20th century. His most important innovation in communicating with the American public was his weekly radio broadcast. Known as “Fireside Chats,” these radio speeches and his warm, earnest speaking style reassured a citizenry jittery over the wrecked economy and the future of the country, and won the public over to his New Deal agenda.

May 6, 1937 – The crash of the Hindenberg: The crash of the huge German airship was the first major catastrophe to be covered by on-the-spot broadcast reporting. Herb Morrison, a radio reporter for the Chicago station WLS, was covering the zeppelin’s mooring in Lakehurst, N.J. His naked, emotional reactions, caught on a recording device he was trying out, would forever color memory of the disaster in the public mind. But in Nazi Germany, the crash of the Hindenberg would be downplayed; considered bad publicity.

1938 – Murrow’s broadcast from Vienna: On March 13, 1938, Murrow and William Shirer reported for CBS on the German annexation of Austria as the Nazi army marched in. The broadcast is significant because it marks both the beginning of the use of broadcast news correspondents (specifically Murrow and his “boys”), and the first part of Hitler’s plans for world domination.

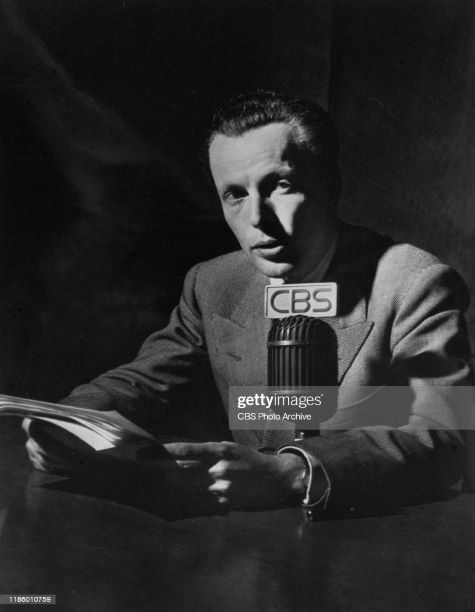

1938 – The War of the Worlds: Orson Welles’ (pictured at left) use of the news report format in his October 30, 1938, radio dramatization of a Martian invasion proved so convincing that a Princeton University study conducted shortly thereafter concluded that one out of six listeners – out of a total estimated audience of six million – believed it was a real news broadcast.

September 1, 1939 – The Second World War begins: Following a fabricated report of Polish terrorists crossing the border, Adolf Hitler unleashed German military. Having practiced new tactics and tested new equipment in the Spanish Civil War, Poland was still able to hold out for six weeks before falling a combined attack by Germany and the Soviet Union. Though Britain and France were unable to send troops, their allegiance with Poland was enough to start a war the would last for six years and kill millions of soldiers and civilians.

Trends in Journalism

On March 1, 1932, shocked Americans learned that the 20-month-old baby of the world’s biggest celebrity and hero, Charles Lindbergh, had been abducted. The dead baby was found near the Lindbergh’s home a month after the first, secret ransom payment was made.

A trail of cash used to pay the ransom eventually led to a German immigrant carpenter named Bruno Richard Hauptmann. The subsequent trial was a prime candidate for “the trial of the century.” Hauptmann was all but convicted by the newsreels and public opinion before the jury’s verdict was read. Despite some holes in the prosecution’s case, Hauptmann was convicted and executed in 1936.

The development of photography as a way to document human experiences for news consumption began with the portable Leica camera and success of Life magazine. Robert Capa took memorable photos while his partner Gerda Taro shot newsreel footage of Republican soldiers fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

Dorothea Lange captured the Okie migrant experience, as well as those of other Americans not previously considered important or pretty enough for the camera.

The newsreel first appeared in the 1900s, and soon newsreels showed before the main feature in more than 15,000 U.S. theatres each week. Relying on melodramatic music scores and staged re-creations of events, newsreels were the technological predecessors of television news. The most popular of these in the 1930s, when the medium hit its stride in popularity, was the March of Time series. Unlike so many of its competitors, this series dealt with controversial subjects, but was not squeamish about recreating events staged for its cameras.

The Federal Communications Act passed by Congress in 1934 re-created the Federal Radio Commission as the Federal Communications Commission, adding telephone and telegraph lines to the commission’s responsibilities. The Act granted commercial radio broadcasters continued hegemony over the airwaves, but did include provisions requiring stations to give equal time to opponents of political candidates who were afforded airtime. The same section denied broadcasters the right to censor a candidate’s material.

Radio continued to grip the imagination of listeners in America and around the world. During the hard years of the Great Depression, radio programs would entertain, inform, and distract listeners from the troubles of their day. However, radio could also cause panic, as Orson Wells’ production of The War of the Worlds would prove.

Batman “The Caped Crusader”, and Superman, the “Man of Steel”, arrived, respectively, in the DC comics series Detective Comics in 1937, and in Action Comics in 1938. They each got their own comic book in the next few years, spawned hosts of imitators, and later enjoyed translation into every other kind of media.

The 1940s

Overview

The 1940s were a decade of tension and transition. Millions of American soldiers left for World War II, and with them went men and women journalists – most notably the “Murrow boys.” Edward R. Murrow, made famous by World War II, began a transition from radio to television.

It was the golden age of comic books. While print media were enjoying success, the war thwarted expansion of broadcast media, especially the new technology of television. The Federal Communication Commission forbade the creation of new radio and television stations during the war years.

The 1940s also saw the death of the beloved Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the fall of both Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany. From the embers of the Second World War came the “Cold War” a simmering competition for world dominance between the democratic, capitalist United States and totalitarian, communist Soviet Union.

Journalists and Media Personalities

Murrow had a profound impact on both radio and television. His ability to paint a picture with words brought him overnight success during his radio news reports from London during World War II. In fact, Murrow is often credited for inventing the radio correspondent. He was originally hired by CBS as “Director of talks”. Murrow and his “boys” reported in gripping detail on the war in Europe. When Murrow returned to the United States in 1941, he was a celebrity. He was reluctant to become actively involved with television, and worked as vice president and director of public affairs for CBS.

Shirer was recruited by Murrow in 1937. As a CBS correspondent in Berlin, he witnessed the Nazi’s rise to power firsthand. He wrote several books about his experience, including Berlin Diary and This is Berlin: Reporting from Nazi Germany. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, published in 1959, is still one of the definitive histories of the era.

Sevareid joined the “Murrow boys” and reported on the war from Europe, Asia, Africa and Central and South America. Sevareid reported on the fall of Paris, and landed with American troops at Omaha Beach, and once had to parachute in the Burma jungle when the plane carrying him experienced engine trouble. Sevareid’s career as a news analyst extended into the 1970s and he worked for The CBS Evening New as a national correspondent.

Nicknamed “Bonnie Prince Charles ” because of his pretty boy looks and extravagant lifestyle, he was sent to cover operation “Torch” in Africa. Collingwood was Murrow’s protégé, and eventually replaced him on Murrow’s television hit Person to Person. Collingwood defended fellow broadcasters accused if communist sympathies during the Red Scare of the 1950s.

Lesueur, the forgotten “Murrow boy,” was a rough and ready journalist. He covered the London Blitz on CBS’s London After Dark, and also traveled to the Soviet Union to cover the eastern front. Lesuere covered the liberation of Paris and the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. He would later leave CBS to work with Voice of America.

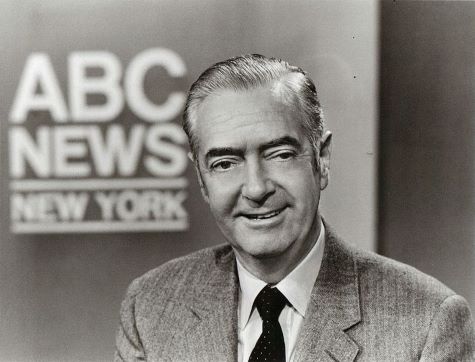

Smith began his career as a foreign correspondent for United Press in London. In 1941, he joined the “Murrow boys” in Berlin. After the war, he worked for CBS’s Washington bureau as chief correspondent and general manager. He left CBS and later became an ABC anchor and a moderator for Face of the Nation.

Brown covered Italy, Yugoslavia, North Africa and the Far East as a “Murrow boy.” While reporting from the H.M.S. Repulse, Brown was forced to abandon ship when Japanese airplanes sunk the battleship. Brown would survive and wrote a book recounting his escape from the sinking Repulse and long return to England. However, Brown became unpopular with the CBS management for his outspoken criticism of war-time censorship. CBS later fired him for editorializing on air.

Burdett began his career at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and was eventually hired as one of the “Murrow Boys.” He later confessed to being a Communist spy during his early war career. In 1955, he willingly testified about his Communist past to the House Un-American Activities Committee. CBS and Murrow protected Burdett and assigned him to Rome where he finished his career.

Breckinridge began her career as a photographer and videographer. During World War II, she was hired by Murrow as the first woman correspondent for CBS. Her career was short-lived. After her marriage to American diplomat, Jefferson Patterson, she was forced to retire from broadcasting. She quickly switched roles and became an active and social diplomatic wife.

Pyle worked as a war correspondent during World War II and accompanied Allied troops in North Africa, Italy and the Pacific. He was awarded the 1944 Pulitzer Prize for distinguished war correspondence. Pyle was known for his ability to bond with the troops and to capture the real emotions of the war. His account of the death of Captain Henry T. Waskow exemplified his skills as a writer.

Bourke-White was born into a family that embraced female equality and ambition. She was a pioneer in the field of photojournalism. Many of her photographs appeared on the cover of Life magazine, and she provided the American people with a grim, visual reality of the war. An independent and determined woman who wasn’t afraid to take risks, she was the first woman to fly on bombing missions, and one of the first photographers to document the horrors of Nazi concentration camps.

After completing a degree in journalism at Columbia University, Higgins was hired by the New York Tribune. She wanted to report on the war in Europe, but it wasn’t until 1944 that she was finally allowed to go to London. She began by reporting on the war from France and later accompanied troops to the Nazi concentration camps in Dachau and Buchenwald. In later wars, Higgins also covered the fall of Seoul, Korea, and made several trips to Vietnam, where she was killed.

Capa, already famous for his photo journalism during the Spanish Civil War, would cover one of the most important battles of the war, the June 6, 1944 invasion of Normandy. Capa would wade ashore with one of the first landing craft and snap many photos before returning to England aboard another landing craft. Most of his photos were destroyed while being developed, but 11 now-famous photos would be saved.

Political Scene

Millions of Americans adored Roosevelt. They admired his strength and determination, and looked to him for support and guidance during times of crisis. His death on April 13, 1945, brought great sadness to the nation. An editorial in The New York Times personified the nation’s shocked and sad reaction: “Men will thank God on their knees a hundred years from now, that Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House.” The beloved president had served four terms, and during that time, guided the United States through both the Great Depression and World War II. Grieving Americans worried about how the future would unfold without him.

Harry S. Truman, a man who hardly knew Roosevelt, and knew even less about the administration’s war plans, became the 33rd president of the U.S. During his presidency, Truman was forced to make several monumental decisions, not the least being the decision to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The Japanese surrender brought sudden peace to the world, and the U.S. emerged from the war as a global power. Americans were not accustomed to thinking in global terms, and for the rest of the decade the U.S. struggled to find her place as an international power.

International tensions remained high after the war was over and Germany was divided into East and West Germany. Eventually, the tensions would grow into the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S.

Social Climate

Advances in technology, including the use of radio and television for news and entertainment, forced Americans to think more about the country’s role in global affairs. The 1940s was a decade that transformed the lives of millions and set the tone for future social, political and economic reforms in the U.S.

After years of struggling through the Great Depression, the U.S. entered the 1940s a weary and wary nation. The country resisted joining the war in Europe, even as the European democracies fell one at a time.

FDR was able to assist Britain through the Lend-Lease program, where the United States “lent” 50 older destroyers for leases on British bases. Initially chastised by American isolationists, opposition disappeared after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Roosevelt quickly mobilized the public’s support and committed the United States to total war. World War II defined the decade and would monopolized the nation’s attention until the Japanese surrender in 1945.

Although the U.S. was fighting overseas in the name of freedom and democracy, at home, both African-Americans and Japanese-Americans suffered great civil rights injustices.

Thousands of African-Americans willingly joined the military to fight for freedom, yet at home, they continued to suffer from segregation and racism. The Pittsburgh Courier launched “The Double V Campaign.” Under the theme of “Democracy: Victory at Home, Victory Abroad,” the effort to rally African-Americans and raise awareness about civil rights issues was very successful. The campaign spread to all parts of the country.

In 1942, Roosevelt ordered the War Relocation Authority to relocate hundreds of thousands of Japanese-Americans to internment camps. The administration was afraid Japan would attempt to orchestrate an attack on the Pacific Coast using Japanese-American spies who lived in the U.S. Many of these individuals were, in fact, U.S. citizens. They were forced to close their stores, leave their jobs, give up their houses, and live in arid relocation camps far from the Pacific coast.

Media Moments

1941 — Pearl Harbor Attacked: On December 7 at 7:55 a.m., Japanese planes began dropping bombs on the U.S. base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack was sudden and devastating. More than 2,400 people died. The very next day, all Americans listened to the radio as Roosevelt declared war on Japan.

1942 — Hitler secretly recorded: Hitler never knowingly let his normal voice or conversations be recorded. As Fuehrer, he permitted recordings only of his carefully staged and rehearsed, formal speeches, delivered in a dramatic and high-pitched voice. But after Hitler delivered such a speech in Helsinki during 1942, a sound engineer left the recording equipment running and captured a private conversation between the dictator and Finnish leader CGE Mannerheim, a Nazi ally.

Hitler, in his rarely heard, low-pitched normal voice, confides to Mannerheim things such as, “Had I finished off France in ’39, then world history would have taken another course. … But then I had to wait until 1940. Then a two-front war, that was bad luck. After that, even we were broken.”

Sound engineer Thor Damen was almost executed after the Gestapo realized what he had done, but Damen managed to fool them into thinking he had destroyed the recording.

According to The Guardian, “It is the only one in existence where Hitler speaks freely,” says Lasse Vihonen, head of the sound archives at Finnish public broadcaster YLE, which operates Radio Finland.

1944 — D-Day, The invasion of Normandy: General Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower’s plan for a cross-channel invasion, code-named “Operation Overlord” was launched by the Allied Expeditionary Forces on June 6, 1945. Allied troops reached the beach near Bernieres, France and poured ashore on the Normandy coast.

April 1945 — Franklin D. Roosevelt dies: The tragic news of Roosevelt’s death was first heard on the radio. Listeners were jolted by broadcast interruptions, and a shocked nation struggled to come to terms with the news.

August 6, 1945 — Atomic bomb dropped: Americans first learned about the atomic bomb 16 hours after it was dropped on Hiroshima. Truman interrupted regular programming to announce that the Japanese “had been repaid many-fold” for their attack on Pearl Harbor.

August 15, 1945 — The Japanese surrender: Even after two bombs had destroyed two Japanese cities, and killed thousands of Japanese citizens, Japan’s Supreme War Council remained deadlocked on the issue of surrender. The Council turned to Emperor Hirohito for a decision, and it was Hirohito who announced Japan’s surrender on Japanese radio on August 15, 1945. The U.S. began broadcasting the news on the radio around midnight.

1947 — The Hollywood 10 refuse to testify before HUAC: Originally created to investigate the Ku Klux Klan and to search out Nazi and fascist plots within the United States, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) refocused its attention on searching for communists, and it found them in the form of Hollywood 10, a group of writers, directors and producers who would refuse to testify before the committee. Others in the motion picture industry did choose to testify, and the Hollywood 10 would be “blacklisted” in Hollywood because of it.

1948 — “Dewey Defeats Truman”: Truman was a serious underdog in the 1948 presidential race. Despite predictions that Tom Dewey would sweep the race, Truman won 303 electoral votes, and a four-year term in the White House. Network radio and television stations were able to flash the news that Truman had won; however, the print media was one step behind. On the morning of November 3, 1948, The Chicago Tribune embarrassingly proclaimed “Dewey Defeats Truman”.

Trends in Journalism

Wire services, newspapers and broadcast organizations sent correspondents to Europe and Asia to report on international developments during World War II. Unlike previous wars, this war was broadcast daily to a listening audience back in the U.S.

The radio played an important role and helped to radically change how people received news and entertainment. The “Murrow Boys” broadcasts from Europe brought the war closer to Americans back home in the states. CBS set a news standard that followed its journalists into television and lasted for decades.

The 1940s were the last decade in which radio was dominant. Television had become a viable technology in the late 1930s, but technical delays and the war both stopped widespread introduction until the late 1940s. After the war, the broadcast networks poured large amounts of money into television. Television began a media revolution in the late 1940s, transforming America, and opening the nation to whole new world of visual communication.

Comic books became successful in the 1940s because they provided cheap and exciting entertainment. Superheroes flourished during a time in which evil was all too real in the world. Captain Marvel, Captain America and Batman battled evil and fed the imagination of the youth. Comic books were also very popular in the military for two reasons: one, the soldiers of World War II were young; and two, comic books were easy to carry.