Latvians belong to the ethno-linguistic group of the Balts. Their language is one of the only two surviving Baltic languages.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The name Latvija is derived from the name of the ancient Latgalians, one of four Indo-EuropeanBaltic tribes (along with Curonians, Selonians and Semigallians), which formed the ethnic core of modern Latvians together with the FinnicLivonians.[20]

Henry of Latvia coined the Latinisations of the country’s name, “Lettigallia” and “Lethia”, both derived from the Latgalians. The terms inspired the variations on the country’s name in Romance languages from “Letonia” and in several Germanic languages from “Lettland”.[21]

Around 3000 BC, the proto-Baltic ancestors of the Latvian people settled on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea.[22] The Balts established trade routes to Rome and Byzantium, trading local amber for precious metals.[23]

In the 12th century in the territory of Latvia, there were lands with their rulers: Vanema, Ventava, Bandava, Piemare, Duvzare, Sēlija, Koknese, Jersika, Tālava and Adzele.[24]

Medieval Period

Although the local people had contact with the outside world for centuries, they became more fully integrated into the European socio-political system in the 12th century.[25] The first missionaries, sent by the Pope, sailed up the Daugava River in the late 12th century, seeking converts.[26] The local people, however, did not convert to Christianity as readily as the Church had hoped.[26]

German crusaders were sent, or more likely decided to go on their own accord as they were known to do. Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile, in 1184, traveling with merchants to Livonia, on a Catholic mission to convert the population from their original pagan beliefs. Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed to produce results, Meinhard plotted to convert Livonians by force of arms.[27]

At the beginning of the 13th century, Germans ruled large parts of what is currently Latvia.[26] Together with southern Estonia, these conquered areas formed the crusader state that became known as Terra Mariana or Livonia. In 1282, Riga, and later the cities of Cēsis, Limbaži, Koknese and Valmiera, became part of the Hanseatic League.[26] Riga became an important point of east–west trading[26] and formed close cultural links with Western Europe.[28] The first German settlers were knights from northern Germany and citizens of northern German towns who brought their Low German language to the region, which shaped many loanwords in the Latvian language.[29]

Reformation Period and Polish and Swedish Rule

After the Livonian War (1558–1583), Livonia (Northern Latvia & Southern Estonia) fell under Polish and Lithuanian rule.[26] The southern part of Estonia and the northern part of Latvia were ceded to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and formed into the Duchy of Livonia (Ducatus Livoniae Ultradunensis). Gotthard Kettler, the last Master of the Order of Livonia, formed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.[30] Though the duchy was a vassal state to Lithuanian Grand Duchy and later of Polish and Lithuanian commonwealth, it retained a considerable degree of autonomy and experienced a golden age in the 16th century. Latgalia, the easternmost region of Latvia, became a part of the Inflanty Voivodeship of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[31]

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, and Russia struggled for supremacy in the eastern Baltic. After the Polish–Swedish War, northern Livonia (including Vidzeme) came under Swedish rule. Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the entire Swedish Empire.[32] Fighting continued sporadically between Sweden and Poland until the Truce of Altmark in 1629.[33] In Latvia, the Swedish period is generally remembered as positive; serfdom was eased, a network of schools was established for the peasantry, and the power of the regional barons was diminished.[34][35]

Several important cultural changes occurred during this time. Under Swedish and largely German rule, western Latvia adopted Lutheranism as its main religion. The ancient tribes of the Couronians, Semigallians, Selonians, Livs, and northern Latgallians assimilated to form the Latvian people, speaking one Latvian language. Throughout all the centuries, however, an actual Latvian state had not been established, so the borders and definitions of who exactly fell within that group are largely subjective. Meanwhile, largely isolated from the rest of Latvia, southern Latgallians adopted Catholicism under Polish/Jesuit influence. The native dialect remained distinct, although it acquired many Polish and Russian loanwords.[36]

Livonia and Courland in the Russian Empire (1795–1917)

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), up to 40 percent of Latvians died from famine and plague.[37] Half the residents of Riga were killed by plague in 1710–1711.[38] The capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710 and the Treaty of Nystad, ending the Great Northern War in 1721, gave Vidzeme to Russia (it became part of the Riga Governorate). The Latgale region remained part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as Inflanty Voivodeship until 1772, when it was incorporated into Russia. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a vassal state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was annexed by Russia in 1795 in the Third Partition of Poland, bringing all of what is now Latvia into the Russian Empire.

During these two centuries Latvia experienced economic and construction boom – ports were expanded (Riga became the largest port in the Russian Empire), railways built; new factories, banks, and a university were established; many residential, public (theatres and museums), and school buildings were erected; new parks formed; and so on.

Numeracy was also higher in the Livonian and Courlandian parts of the Russian Empire, which may have been influenced by the Protestant religion of the inhabitants.[40]

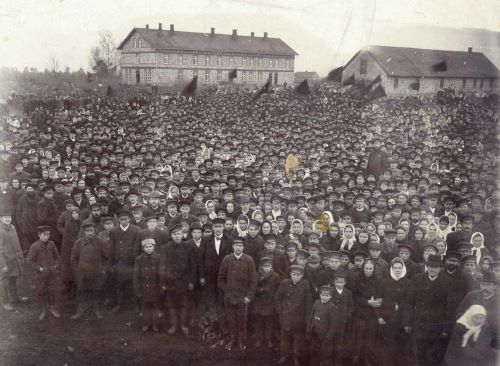

Nacionālā enciklopēdija, Wikimedia CommonsDuring the 19th century, the social structure changed dramatically.[41] A class of independent farmers established itself after reforms allowed the peasants to repurchase their land, but many landless peasants remained, quite a lot Latvians left for the cities and sought for education, industrial jobs.[41] There also developed a growing urban proletariat and an increasingly influential Latvian bourgeoisie.[41] The Young Latvian (Latvian: Jaunlatvieši) movement laid the groundwork for nationalism from the middle of the century, many of its leaders looking to the Slavophiles for support against the prevailing German-dominated social order.[42][43]

The rise in use of the Latvian language in literature and society became known as the First National Awakening.[42] The Young Latvians were largely eclipsed by the New Current, a broad leftist social and political movement, in the 1890s.[44] Popular discontent exploded in the 1905 Russian Revolution, which took a nationalist character in the Baltic provinces.[45]

Declaration of Independence

World War I devastated the territory of what became the state of Latvia, and other western parts of the Russian Empire. Demands for self-determination were initially confined to autonomy, until a power vacuum was created by the Russian Revolution in 1917, followed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany in March 1918, then the Allied armistice with Germany on 11 November 1918. On 18 November 1918, in Riga, the People’s Council of Latvia proclaimed the independence of the new country and Kārlis Ulmanis was entrusted to set up a government and he took the position of Prime Minister.[46]

The General representative of Germany August Winnig formally handed over political power to the Latvian Provisional Government on 26 November. On November 18, the Latvian People’s Council entrusted him to set up the government. He took the office of Minister of Agriculture from November 18 to December 19. He took a position of Prime Minister from 19 November 1918 to 13 July 1919.

The war of independence that followed was part of a general chaotic period of civil and new border wars in Eastern Europe. Estonian and Latvian forces defeated the Germans at the Battle of Wenden in June 1919,[47] and a massive attack by a predominantly German force—the West Russian Volunteer Army—under Pavel Bermondt-Avalov was repelled in November.

A freely elected Constituent assembly convened on 1 May 1920, and adopted a liberal constitution, the Satversme, in February 1922.[48] The constitution was partly suspended by Kārlis Ulmanis after his coup in 1934 but reaffirmed in 1990. Since then, it has been amended and is still in effect in Latvia today. With most of Latvia’s industrial base evacuated to the interior of Russia in 1915, radical land reform was the central political question for the young state. In 1897, 61.2% of the rural population had been landless; by 1936, that percentage had been reduced to 18%.[49]

By 1923, the extent of cultivated land surpassed the pre-war level. Innovation and rising productivity led to rapid growth of the economy, but it soon suffered from the effects of the Great Depression. On 15 May 1934, Ulmanis staged a bloodless coup, establishing a nationalist dictatorship that lasted until 1940.[50] After 1934, Ulmanis established government corporations to buy up private firms with the aim of “Latvianising” the economy.[51]

Latvia in World War II

Early in the morning of 24 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a 10-year non-aggression pact, called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[52] The pact contained a secret protocol, revealed only after Germany’s defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet “spheres of influence”.[53] In the north, Latvia, Finland and Estonia were assigned to the Soviet sphere.[53] A week later, on 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland; on 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland as well.[54]: 32

After the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, most of the Baltic Germans left Latvia by agreement between Ulmanis’s government and Nazi Germany under the Heim ins Reich programme.[55] In total 50,000 Baltic Germans left by the deadline of December 1939, with 1,600 remaining to conclude business and 13,000 choosing to remain in Latvia.[55] Most of those who remained left for Germany in summer 1940, when a second resettlement scheme was agreed.[56] The racially approved being resettled mainly in Poland, being given land and businesses in exchange for the money they had received from the sale of their previous assets.[54]: 46

On 5 October 1939, Latvia was forced to accept a “mutual assistance” pact with the Soviet Union, granting the Soviets the right to station between 25,000 and 30,000 troops on Latvian territory.[57] State administrators were murdered and replaced by Soviet cadres.[58] Elections were held with single pro-Soviet candidates listed for many positions. The resulting people’s assembly immediately requested admission into the USSR, which the Soviet Union granted.[58] Latvia, then a puppet government, was headed by Augusts Kirhenšteins.[59] The Soviet Union incorporated Latvia on 5 August 1940, as the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Soviets dealt harshly with their opponents – prior to Operation Barbarossa, in less than a year, at least 34,250 Latvians were deported or killed.[60] Most were deported to Siberia where deaths were estimated at 40 percent.[54]: 48

On 22 June 1941, German troops attacked Soviet forces in Operation Barbarossa.[61] There were some spontaneous uprisings by Latvians against the Red Army which helped the Germans. By 29 June Riga was reached and with Soviet troops killed, captured or retreating, Latvia was left under the control of German forces by early July.[62][54]: 78–96 The occupation was followed immediately by SS Einsatzgruppen troops, who were to act in accordance with the Nazi Generalplan Ost that required the population of Latvia to be cut by 50 percent.[54]: 64 [54]: 56

Under German occupation, Latvia was administered as part of Reichskommissariat Ostland.[63] Latvian paramilitary and Auxiliary Police units established by the occupation authority participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities.[50] 30,000 Jews were shot in Latvia in the autumn of 1941.[54]: 127 Another 30,000 Jews from the Riga ghetto were killed in the Rumbula Forest in November and December 1941, to reduce overpopulation in the ghetto and make room for more Jews being brought in from Germany and the West.[54]: 128 There was a pause in fighting, apart from partisan activity, until after the siege of Leningrad ended in January 1944, and the Soviet troops advanced, entering Latvia in July and eventually capturing Riga on 13 October 1944.[54]: 271

More than 200,000 Latvian citizens died during World War II, including approximately 75,000 Latvian Jews murdered during the Nazi occupation.[50] Latvian soldiers fought on both sides of the conflict, mainly on the German side, with 140,000 men in the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS,[64] The 308th Latvian Rifle Division was formed by the Red Army in 1944. On occasions, especially in 1944, opposing Latvian troops faced each other in battle.[54]: 299

In the 23rd block of the Vorverker cemetery, a monument was erected after the Second World War for the people of Latvia who had died in Lübeck from 1945 to 1950.

Soviet Era (1940–1941, 1944–1991)

In 1944, when Soviet military advances reached Latvia, heavy fighting took place in Latvia between German and Soviet troops, which ended in another German defeat. In the course of the war, both occupying forces conscripted Latvians into their armies, in this way increasing the loss of the nation’s “live resources”. In 1944, part of the Latvian territory once more came under Soviet control. The Soviets immediately began to reinstate the Soviet system. After the German surrender, it became clear that Soviet forces were there to stay, and Latvian national partisans, soon joined by some who had collaborated with the Germans, began to fight against the new occupier.[65]

Anywhere from 120,000 to as many as 300,000 Latvians took refuge from the Soviet army by fleeing to Germany and Sweden.[66] Most sources count 200,000 to 250,000 refugees leaving Latvia, with perhaps as many as 80,000 to 100,000 of them recaptured by the Soviets or, during few months immediately after the end of war,[67] returned by the West.[68] The Soviets reoccupied the country in 1944–1945, and further deportations followed as the country was collectivised and Sovietised.[50]

On 25 March 1949, 43,000 rural residents (“kulaks”) and Latvian nationalists were deported to Siberia in a sweeping Operation Priboi in all three Baltic states, which was carefully planned and approved in Moscow already on 29 January 1949.[69] This operation had the desired effect of reducing the anti Soviet partisan activity.[54]: 326 Between 136,000 and 190,000 Latvians, depending on the sources, were imprisoned or deported to Soviet concentration camps (the Gulag) in the post war years, from 1945 to 1952.[70]

In the post-war period, Latvia was made to adopt Soviet farming methods. Rural areas were forced into collectivization.[71] An extensive program to impose bilingualism was initiated in Latvia, limiting the use of Latvian language in official uses in favor of using Russian as the main language. All of the minority schools (Jewish, Polish, Belarusian, Estonian, Lithuanian) were closed down leaving only two media of instructions in the schools: Latvian and Russian.[72] An influx of new colonists, including laborers, administrators, military personnel and their dependents from Russia and other Soviet republics started. By 1959 about 400,000 Russian settlers arrived and the ethnic Latvian population had fallen to 62%.[73]

Since Latvia had maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists, Moscow decided to base some of the Soviet Union’s most advanced manufacturing in Latvia. New industry was created in Latvia, including a major machinery factory RAF in Jelgava, electrotechnical factories in Riga, chemical factories in Daugavpils, Valmiera and Olaine—and some food and oil processing plants.[74] Latvia manufactured trains, ships, minibuses, mopeds, telephones, radios and hi-fi systems, electrical and diesel engines, textiles, furniture, clothing, bags and luggage, shoes, musical instruments, home appliances, watches, tools and equipment, aviation and agricultural equipment and long list of other goods. Latvia had its own film industry and musical records factory (LPs). To maintain and expand industrial production, skilled workers were migrating from all over the Soviet Union, decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians in the republic.[75] The population of Latvia reached its peak in 1990 at just under 2.7 million people.

In late 2018 the National Archives of Latvia released a full alphabetical index of some 10,000 people recruited as agents or informants by the Soviet KGB. ‘The publication, which followed two decades of public debate and the passage of a special law, revealed the names, code names, birthplaces and other data on active and former KGB agents as of 1991, the year Latvia regained its independence from the Soviet Union.’[76]

Restoration of Independence in 1991

In the second half of the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started to introduce political and economic reforms in the Soviet Union that were called glasnost and perestroika. In the summer of 1987, the first large demonstrations were held in Riga at the Freedom Monument—a symbol of independence. In the summer of 1988, a national movement, coalescing in the Popular Front of Latvia, was opposed by the Interfront. The Latvian SSR, along with the other Baltic Republics was allowed greater autonomy, and in 1988, the old pre-war Flag of Latvia flew again, replacing the Soviet Latvian flag as the official flag in 1990.[77][78]

In 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a resolution on the Occupation of the Baltic states, in which it declared the occupation “not in accordance with law”, and not the “will of the Soviet people”. Pro-independence Popular Front of Latvia candidates gained a two-thirds majority in the Supreme Council in the March 1990 democratic elections. On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Council adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia, and the Latvian SSR was renamed Republic of Latvia.[79]

However, the central power in Moscow continued to regard Latvia as a Soviet republic in 1990 and 1991. In January 1991, Soviet political and military forces unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Republic of Latvia authorities by occupying the central publishing house in Riga and establishing a Committee of National Salvation to usurp governmental functions. During the transitional period, Moscow maintained many central Soviet state authorities in Latvia.[79]

The Popular Front of Latvia advocated that all permanent residents be eligible for Latvian citizenship, however, universal citizenship for all permanent residents was not adopted. Instead, citizenship was granted to persons who had been citizens of Latvia on the day of loss of independence in 1940 as well as their descendants. As a consequence, the majority of ethnic non-Latvians did not receive Latvian citizenship since neither they nor their parents had ever been citizens of Latvia, becoming non-citizens or citizens of other former Soviet republics. By 2011, more than half of non-citizens had taken naturalization exams and received Latvian citizenship, but in 2015 there were still 290,660 non-citizens in Latvia, which represented 14.1% of the population. They have no citizenship of any country, and cannot participate in the parliamentary elections.[80] Children born to non-nationals after the re-establishment of independence are automatically entitled to citizenship.

The Republic of Latvia declared the end of the transitional period and restored full independence on 21 August 1991, in the aftermath of the failed Soviet coup attempt.[5] Latvia resumed diplomatic relations with Western states, including Sweden.[81] The Saeima, Latvia’s parliament, was again elected in 1993. Russia ended its military presence by completing its troop withdrawal in 1994 and shutting down the Skrunda-1 radar station in 1998. The major goals of Latvia in the 1990s, to join NATO and the European Union, were achieved in 2004. The NATO Summit 2006 was held in Riga.[82] Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga was President of Latvia from 1999 until 2007. She was the first female head of state in the former Soviet block state and was active in Latvia joining both NATO and the European Union in 2004.[83]

Approximately 72% of Latvian citizens are Latvian, while 20% are Russian; less than 1% of non-citizens are Latvian, while 71% are Russian.[84] The government denationalized private property confiscated by the Soviets, returning it or compensating the owners for it, and privatized most state-owned industries, reintroducing the prewar currency. Albeit having experienced a difficult transition to a liberal economy and its re-orientation toward Western Europe, Latvia is one of the fastest growing economies in the European Union. In 2014, Riga was the European Capital of Culture,[85] Latvia joined the eurozone and adopted the EU single currency euro as the currency of the country[86] and Latvian Valdis Dombrovskis was named vice-president of the European Commission.[87] In 2015 Latvia held the presidency of Council of the European Union.[88] Big European events have been celebrated in Riga such as the Eurovision Song Contest 2003[89] and the European Film Awards 2014.[90] On 1 July 2016, Latvia became a member of the OECD.[91]

Appendix

Endnotes

- “Latvia in Brief” (PDF). Latvian Institute. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- “Baltic Online”. The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- “Data: 3000 BC to 1500 BC”. The European Ethnohistory Database. The Ethnohistory Project. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- A History of Rome, M Cary and HH Scullard, p455-457, Macmillan Press

- Latvijas vēstures atlants, Jānis Turlajs, page 12, Karšu izdevniecība Jāņa sēta

- “Data: Latvia”. Kingdoms of Northern Europe – Latvia. The History Files. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- “Latvian History, Lonely Planet”. Lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- “The Crusaders”. City Paper. 22 March 2006. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- “History of Latvia – Lonely Planet Travel Information”. www.lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Johann Sehwers (1918). Die deutschen Lehnwörter im Lettischen: Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der hohen philosophischen Fakultät I der Universität Zürich (in German). Berichthaus.

- Ceaser, Ray A. (June 2001). “Duchy of Courland”. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2 March 2003. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- O’Connor, Kevin (3 October 2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Kasekamp, p. 47

- Rickard, J. “Truce of Altmark, 12 September 1629”. www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- H. Strods, “‘Dobrye Shvedskie Vremena’ v Istoriografii Latvii (Konets XVIII V. – 70-E Gg. XX V.). [“‘The good Swedish times’ in Latvian historiography: from the late 18th century to the 1970s”] Skandinavskiy Sbornik, 1985, Vol. 29, pp. 188–199

- J. T. Kotilaine (1999). “Riga’s Trade With its Muscovite Hinterland in the Seventeenth Century”. Journal of Baltic Studies. 30 (2): 129–161.

- V. Stanley Vardys (1987). “The Role of the Churches in the Maintenance of Regional and National Identity in the Baltic Republics”. Journal of Baltic Studies. 18 (3): 287–300.

- Kevin O’Connor (1 January 2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 29–.

- “Collector Coin Dedicated to 18th Century Riga”. Archived from the original on 19 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.. Bank of Latvia.

- Lazdins, Janiz (2 July 2011). “THE ORIGINS OF A CIVIL SOCIETY BASED ON DEMOCRATICALLY LEGITIMATE VALUES IN BALTICS AFTER ABOLITION OF SERFDOM” (PDF). doi.org.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 50.

- “Latvian national awakening (1860-1918)”. OnLatvia.com. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- “Latvians in the Second Half of the 19th Century and the Early 20th Century: National Identity, Culture and Social Life”. National History Museum of Latvia. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- “Another Baltic Postcolonialism: Young Latvians, Baltic Germans, and the emergence of Latvian National Movement”. Nationalities Papers. Cambridge University Press. 42 (1): 88–107. 20 November 2018.

- Šiliņš, Jānis. “Jaunā strāva”. Nacionālā enciklopēdija (in Latvian). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Lapa, Līga. “1905. gada revolūcija Latvijā”. Nacionālā enciklopēdija (in Latvian). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- “Kārlis Ulmanis | Valsts prezidenta kanceleja”. www.president.lv. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- “Cēsis, Battle of | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)”. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Bleiere, p. 155

- Bleiere, p. 195

- “Timeline: Latvia”. BBC News. 20 January 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Nicholas Balabkins; Arnolds P. Aizsilnieks (1975). Entrepreneur in a small country: a case study against the background of the Latvian economy, 1919–1940. Exposition Press. pp. xiv, 143.

- “The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact – archive, August 1939”. the Guardian. 24 July 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact Archived 14 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, executed 23 August 1939

- Buttar, Prit (21 May 2013). Between Giants.

- Lumans, pp. 71–74

- Lumans pp. 110–111

- Lumans, p. 79

- Wettig, Gerhard, Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, Landham, Md, 2008,9, pp. 20–21

- Lumans, pp. 98–99

- Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. p. 334.

- “Operation Barbarossa”. HISTORY. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- “History of Latvia: A brief synopsis”. www.mfa.gov.lv. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- “Estonia – RomArchive”. www.romarchive.eu. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- “Patriots or Nazi collaborators? Latvians march to commemorate SS veterans. Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine” The Guardian. 16 March 2010

- Lumans, pp. 395–396

- Lumans, p. 349

- Lumans, pp. 384–385

- Lumans, p. 391

- Strods, Heinrihs; Kott, Matthew (2002). “The File on Operation ‘Priboi’: A Re-Assessment of the Mass Deportations of 1949”. Journal of Baltic Studies. 33 (1): 1–36.

- Lumans, pp. 398–399

- Bleiere, p. 384

- Bleiere, p. 411

- Bleiere, p. 418

- Bleiere, p. 379

- Lumans, p. 400

- contributor, Vladimir Kara-Murza DemocracyPost. “Opinion | Latvia opens its KGB archives — while Russia continues to whitewash its past”. Washington Post.

- “Flag Log’s World Flag Chart 1991”. flaglog.com. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- More-detailed discussion in Daina Stukuls Eglitis, Imagining the Nation: History, Modernity, and Revolution in Latvia State College PA: Pennsylvania State Press, 2010), 41-46.

- Eglitis, Daina Stukuls (1 November 2010). Imagining the Nation: History, Modernity, and Revolution in Latvia. Penn State Press.

- “Stories of Statelessness: Latvia and Estonia – IBELONG”. 12 January 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015.

- “The King holds an audience with Latvia’s President”. Swedish Royal Court. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- “NATO Press Release”. www.nato.int. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- “From child refugee to president: Latvia’s Vaira Vike-Freiberga”. BBC News. 4 August 2019.

- Commercio Michele E (2003). “Emotion and Blame in Collective Action: Russian Voice in Kyrgyzstan and Latvia”. Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 489–512.

- “Riga – European Capital of Culture (ECoC) in 2014”. Diversity of Cultural Expressions. 29 April 2016.

- Traykov, Peter (15 February 2014). “Latvia in the euro zone: national economic outlook for 2014”. Nouvelle-europe.eu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- “Valdis Dombrovskis Named as European Commission’s Vice President”. [Latvia.eu]. 10 September 2014.

- “Latvian Presidency of the Council of the European Union” (PDF). Global Agricultural Information Network. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- “Final of Riga 2003”. Eurovision.tv.

- “European Film Academy : European Film Awards 2014 go to Riga”. www.europeanfilmacademy.org.

- “Latvia’s accession to the OECD”. OECD. 1 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Arveds, Švābe (1949). The Story of Latvia: A Historical Survey. Stockholm: Latvian National Foundation.

- Bleiere, Daina; and Ilgvars Butulis; Antonijs Zunda; Aivars Stranga; Inesis Feldmanis (2006). History of Latvia: the 20th century. Rīga: Jumava.

- Cimdiņa, Ausma; and Deniss Hanovs (eds.) (2011). Latvia and Latvians: A People and a State in Ideas, Images and Symbols. Rīga: Zinātne Publishers.

- Dreifelds, Juris (1996). Latvia in Transition. Cambridge University Press.

- Dzenovska, Dace. School of Europeanness: Tolerance and other lessons in political liberalism in Latvia (Cornell University Press, 2018).

- Ģērmanis, Uldis (2007). The Latvian Saga. Rīga: Atēna.

- Hazans, Mihails. “Emigration from Latvia: Recent trends and economic impact.” in Coping with emigration in Baltic and East European countries (2013) pp: 65–110. online

- Lumans, Valdis O. (2006). Latvia in World War II. Fordham University Press.

- Meyendorff, Alexander Feliksovich (1922). “Latvia” . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Plakans, Andrejs (1998). Historical Dictionary of Latvia (2nd ed.). Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2010). The A to Z of Latvia. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

- Plakans, Andrejs (1995). The Latvians: A Short History. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

- Pabriks, Artis, and Aldis Purs. Latvia: the challenges of change (Routledge, 2013).

- Rutkis, Jānis (ed.) (1967). Latvia: Country & People. Stockholm: Latvian National Foundation.

- Turlajs, Jānis (2012). Latvijas vēstures atlants. Rīga: Karšu izdevniecība Jāņa sēta.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 03.01.2001, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.