The winning supporters of ratification of the Constitution were called Federalists and the opponents were called Anti-Federalists.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The First Political Parties: Federalists and Anti-Federalists

Overview

The winning supporters of ratification of the Constitution were called Federalists, the opponents were called Anti-Federalists.

The Federalist Era was a period in American history from roughly 1789-1801 when the Federalist Party was dominant in American politics. This period saw the adoption of the United States Constitution and the expansion of the federal government. In addition, the era saw the growth of a strong nationalistic government under the control of the Federalist Party. Among the most important events of this period were the foreign entanglements between France and Great Britain, the assertion of a strong centralized federal government, and the creation of political parties. The First Party System of the United States featured the Federalist Party and the Democratic- Republican Party (also known as the Anti-Federalist Party).

The United States Constitution was written in 1787 and unanimously ratified by the states in 1788, taking effect in 1789. The winning supporters of ratification of the Constitution were called Federalists and the opponents were called Anti-Federalists. The immediate problem faced by the Federalists was not simply one of acceptance of the Constitution but the more fundamental concern of legitimacy for the government of the new republic. With this challenge in mind, the new national government needed to act with the idea that every act was being carried out for the first time and would therefore have great significance and be viewed along the lines of the symbolic as well as practical implications. The first elections to the new United States Congress returned heavy Federalist majorities. The first Anti-Federalist movement opposed the draft Constitution in 1788, primarily because they lacked a Bill of Rights. The Anti-Federalists, or Democrat-Republicans, objected to the new powerful central government and the loss of prestige for the states, and saw the Constitution as a potential threat to personal liberties. During the ratification process the Anti-Federalists presented a significant opposition in all but three states. A major stumbling block for the Anti-Federalists, however, was that the supporters of the Constitution were more deeply committed and outmaneuvered the less energetic opposition.

Federalists v. Anti-Federalists

The dynamic force in the Presidency of George Washington was the secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton had the vision of a strong national government and a strong national economy. He devised a complex multi-faceted program to achieve that goal and simultaneously solved the debt problem for most of the states. Hamilton created a financial system for national and international stability that included paying off the national debt and laying the infrastructure for further economic development. Hamilton’s programs included:

- the assumption of the state’s Revolutionary War debts;

- the payoffs of the debts of the old Continental Congress;

- the payoffs of loans from foreign treasuries and investors;

- the creation of a system of taxes and tariffs to pay for the debt; and

- a First Bank of the United States to handle the finances.

Congress approved Hamilton’s programs, which would later be labeled Federalist, over the opposition of the old Anti-Federalists element, which increasingly coalesced under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. In order to build a national network in support of his programs, Hamilton created a coalition of supporters in every city and state, often consisting of prominent businessmen and financiers. Hamilton’s network of supporters grew into the “Federalist Party” that included most, but not all, of those Federalists who supported the Constitution in 1788. A major emphasis of Hamilton’s policies and indeed the general outlook for the Federalist Party was that the federal government was to preside over the national economy.

Rise of Political Parties

Federalists during the ratification period had been unified around the Constitution and support for its form of government. Following the acceptance of the Constitution, the initial Federalist movement faded briefly only to be taken up by a second movement centered upon the support for Alexander Hamilton’s policies of a strong nationalist government, loose construction of the Constitution, and mercantile economic policies. The support around these policies eventually established the first official political party in the United States as the Federalist Party. The Party reached its political apex with the election of the strongly Federalist President John Adams. However the defeat of Adams in the election of 1800 and the death of Hamilton led to the decline of the Federalist Party from which it did not recover. While there were still Federalists after 1800, the party never again enjoyed the power and influence it had held earlier. One of the Federalists Era’s greatest accomplishments was that republican government survived and took root in the United States.

Republicans, or the Democratic-Republican Party, was founded in 1792 by Jefferson and James Madison. The party was created in order to oppose the policies of Hamilton and the Federalist Party. In contrast to the Federalists, the Republican supported a strict construction interpretation of the Constitution, and denounced many of Hamilton’s proposals (especially the national bank) as unconstitutional. The party promoted states’ rights and the primacy of the yeoman farmer over bankers, industrialists, merchants, and other monied interests. The party supported states’ rights as a measure against the tyrannical nature of a large centralized government that they feared the Federal government could have easily become. It would be Jefferson and the Republican Party that would replace the Federalist Party domination of politics following the election of 1800.

Political Parties from 1800–1824

The First Party System refers to political party system existing in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824.

The First Party System is a model of American politics used by political scientists and historians to periodize the political party system existing in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. Rising out of the Federalist v. Anti-Federalist debates, it featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist Party, created largely by Alexander Hamilton, and the rival Democratic-Republican Party formed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The Federalists were dominant until 1800, and the Republicans were dominant after 1800.

In an analysis of the contemporary party system, Jefferson wrote on Feb. 12, 1798: “Two political Sects have arisen within the US, the one believing that the executive is the branch of our government which the most needs support; the other, that like the analogous branch in the English Government, it is already too strong for the republican parts of the Constitution; and therefore in equivocal cases they incline to the legislative powers: the former of these are called federalists, sometimes aristocrats or monocrats, and sometimes tories, after the corresponding sect in the English Government of exactly the same definition: the latter are stiled republicans, whigs, jacobins, anarchists, disorganizers, etc. these terms are in familiar use with most persons. ”

Both parties originated in national politics, but later expanded their efforts to gain supporters and voters in every state. The Federalists appealed to the business community, the Republicans to the planters and farmers. By 1796 politics in every state was nearly monopolized by the two parties, with party newspapers and caucuses becoming especially effective tools to mobilize voters.

The Federalists promoted the financial system of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, which emphasized federal assumption of state debts, a tariff to pay off those debts, a national bank to facilitate financing, and encouragement of banking and manufacturing. The Republicans, based in the plantation South, opposed a strong executive power, were hostile to a standing army and navy, demanded a limited reading of the Constitutional powers of the federal government, and strongly opposed the Hamilton financial program. Perhaps even more important was foreign policy, where the Federalists favored Britain because of its political stability and its close ties to American trade, while the Republicans admired the French and the French Revolution. Jefferson was especially fearful that British aristocratic influences would undermine Republicanism. Britain and France were at war from 1793 through 1815, with one brief interruption. American policy was neutrality, with the Federalists hostile to France, and the Republicans hostile to Britain. The Jay Treaty of 1794 marked the decisive mobilization of the two parties and their supporters in every state. President George Washington, while officially nonpartisan, generally supported the Federalists, and that party made Washington their iconic hero. The First Party System ended during the Era of Good Feelings (1816–1824), as the Federalists shrank to a few isolated strongholds and the Republicans lost unity. In 1824-28, as the Second Party System emerged, the Republican Party split into the Jacksonian faction, which became the modern Democratic Party in the 1830s, and the Henry Clay faction, which was absorbed by Clay’s Whig Party.

Jacksonian Democrats: 1824–1860

Overview

Jacksonian democracy is the political movement toward greater democracy for the common man typified by American politician Andrew Jackson and his supporters. Jackson’s policies followed the era of Jeffersonian democracy which dominated the previous political era. The Democratic-Republican Party of the Jeffersonians became factionalized in the 1820s. Jackson’s supporters began to form the modern Democratic Party; they fought the rival Adams and Anti-Jacksonian factions, which soon emerged as the Whigs.

More broadly, the term refers to the period of the Second Party System (mid-1824–1860) when the democratic attitude was the spirit of that era. It can be contrasted with the characteristics of Jeffersonian democracy. Jackson’s equal political policy became known as “Jacksonian Democracy,” subsequent to ending what he termed a ” monopoly ” of government by elites. Jeffersonians opposed inherited elites but favored educated men while the Jacksonians gave little weight to education. The Whigs were the inheritors of Jeffersonian Democracy in terms of promoting schools and colleges. During the Jacksonian era, the suffrage was extended to (nearly) all white male adult citizens.

In contrast to the Jeffersonian era, Jacksonian democracy promoted the strength of the presidency and executive branch at the expense of Congress, while also seeking to broaden the public’s participation in government. They demanded elected (not appointed) judges and rewrote many state constitutions to reflect the new values. In national terms the Jacksonians favored geographical expansion, justifying it in terms of Manifest Destiny. There was usually a consensus among both Jacksonians and Whigs that battles over slavery should be avoided. The Jacksonian Era lasted roughly from Jackson’s 1828 election until the slavery issue became dominant after 1850 and the American Civil War dramatically reshaped American politics as the Third Party System emerged.

Jacksonian democracy was built on the following general principles:

Expanded Suffrage

The Jacksonians believed that voting rights should be extended to all white men. By 1820, universal white male suffrage was the norm, and by 1850 nearly all requirements to own property or pay taxes had been dropped.

Manifest Destiny

This was the belief that white Americans had a destiny to settle the American West and to expand control from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific and that the West should be settled by yeoman farmers. However, the Free Soil Jacksonians, notably Martin Van Buren, argued for limitations on slavery in the new areas to enable the poor white man to flourish; they split with the main party briefly in 1848. The Whigs generally opposed Manifest Destiny and expansion, saying the nation should build up its cities.

Patronage

Also known as the spoils system, patronage was the policy of placing political supporters into appointed offices. Many Jacksonians held the view that rotating political appointees in and out of office was not only the right but also the duty of winners in political contests. Patronage was theorized to be good because it would encourage political participation by the common man and because it would make a politician more accountable for poor government service by his appointees. Jacksonians also held that long tenure in the civil service was corrupting, so civil servants should be rotated out of office at regular intervals. However, it often led to the hiring of incompetent and sometimes corrupt officials due to the emphasis on party loyalty above any other qualifications.

Strict Constructionism

Like the Jeffersonians who strongly believed in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, Jacksonians initially favored a federal government of limited powers. Jackson said that he would guard against “all encroachments upon the legitimate sphere of State sovereignty”. This is not to say that Jackson was a states’ rights extremist; indeed, the Nullification Crisis would find Jackson fighting against what he perceived as state encroachments on the proper sphere of federal influence. This position was one basis for the Jacksonians’ opposition to the Second Bank of the United States. As the Jacksonians consolidated power, they more often advocated expanding federal power and presidential power in particular.

Laissez-Faire Economics

Complementing a strict construction of the Constitution, the Jacksonians generally favored a hands-off approach to the economy, as opposed to the Whig program sponsoring modernization, railroads, banking, and economic growth. The leader was William Leggett of the Locofocos in New York City.

Banking

In particular, the Jacksonians opposed government-granted monopolies to banks, especially the national bank, a central bank known as the Second Bank of the United States. Despite this, Jackson did not actively seek to destroy or fight the Bank, only vetoing the Bank’s recharter and subsequently pulling out federal reserves. The Whigs, who strongly supported the Bank, were led by Daniel Webster and Nicholas Biddle, the bank chairman. Jackson himself was opposed to all banks, because he believed they were devices to cheat common people; he and many followers believed that only gold and silver could be money.

The Golden Age: 1860–1932

Overview

Despite outward indicators of prosperity, the Gilded Age (late 1860s to 1896) was an era characterized by turmoil and political contention.

In United States history, the Gilded Age was the period following the Civil War, running from the late 1860s to about 1896 when the next era began, the Progressive Era. The term was coined by writers Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, which satirized what they believed to be an era of serious social problems obscured by a thin veneer of prosperity.

The Gilded Age was a time of enormous growth that attracted millions of European immigrants. Railroads were the major industry, but the factory system, mining, and labor unions also gained in importance. Despite the growth, there was serious cause for concern, which manifested in two major nationwide depressions, known as the Panic of 1873 and the Panic of 1893. Furthermore, most of the growth and prosperity came in the North and West – states that had been part of the Union. States in the South, part of the defeated Confederate States of America, remained economically devastated; their economies became increasingly tied to cotton and tobacco production, which suffered low prices. African Americans in the south experienced the worst setbacks, as they were stripped of political power and voting rights.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the U.S. economy rose at the fastest rate in its history, with real wages, wealth, gross domestic product (GDP), and capital formation all increasing rapidly. Between 1865 and 1898, the output of wheat increased by 256%, corn by 222%, coal by 800% and miles of railway track by 567%. Thick national networks for transportation and communication were created. The corporation became the dominant form of business organization, and a managerial revolution transformed business operations. By the beginning of the 20th century, per capita income and industrial production in the United States led the world, with per capita incomes double that of Germany or France, and 50% higher than Britain.

Politics in the Gilded Age

Gilded Age politics, called the Third Party System, were characterized by rampant corruption and intense competition between the two parties (with minor parties coming and going), especially on issues of Prohibitionist, labor unions and farmers. The Democrats and Republicans fought over control of offices as well as major economic issues. The dominant political issues included rights for African Americans, tariff policies and monetary policies. Reformers worked for civil service reform, prohibition and women’s suffrage, while philanthropists built colleges and hospitals, and the many religious denominations exerted a major sway in both politics and everyday life.

Voter turnout was very high and often exceeded 80% or even 90% in some states as the parties were adamant about rallying their loyal supporters. Competition was intense and elections were very close. In the South, lingering resentment over the Civil War meant that most states would vote Democrat. After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, competition in the South took place mainly inside the Democratic Party. Nationwide, voter turnout fell sharply after 1900.

The Third Party System (1854-1890s)

The Third Party System lasted from about 1854 to the mid-1890s, and featured profound developments in issues of nationalism, modernization, and race. It was dominated by the new Republican Party (also known as the Grand Old Party or GOP), which claimed success in saving the Union, abolishing slavery and enfranchising the freedmen, while adopting many Whiggish modernization programs such as national banks, railroads, high tariffs, homesteads, social spending (such as on greater Civil War veteran pension funding), and aid to land grant colleges. While most elections from 1874 through 1892 were extremely close, the opposition Democrats won only the 1884 and 1892 presidential elections. The northern and western states were largely Republican, save for closely balanced New York, Indiana, New Jersey, and Connecticut. After 1874, the Democrats took control of the “Solid South. ”

The Fourth Party System (1896-1932)

The Fourth Party System lasted from about 1896 to 1932, and was dominated by the Republican Party, excepting the 1912 split in which Democrats held the White House for eight years. American history texts usually call it the Progressive Era, and it included World War I and the start of the Great Depression. The period featured a transformation from the issues of the Third Party System, instead focusing on domestic issues such as regulation of railroads and large corporations (“trusts”), the money issue (gold versus silver), the protective tariff, the role of labor unions, child labor, the need for a new banking system, corruption in party politics, primary elections, direct election of senators, racial segregation, efficiency in government, women’s suffrage, and control of immigration. Foreign policy centered on the 1898 Spanish-American War, Imperialism, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, and the creation of the League of Nations.

The Modern Era of Political Parties

Modern politics in the United States is a two-party system dominated by the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. One of these two parties has won every United States presidential election since 1852 and has controlled the United States Congress since at least 1856.

The Democratic Party is one of two major political parties in the United States, and is the oldest political party in the world. Since the division of the Republican Party in the election of 1912, it has positioned itself as progressive and supporting labor in economic as well as social matters. The economic philosophy of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which has strongly influenced American liberalism, has shaped much of the party’s agenda since 1932, and Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition controlled the White House until 1968.

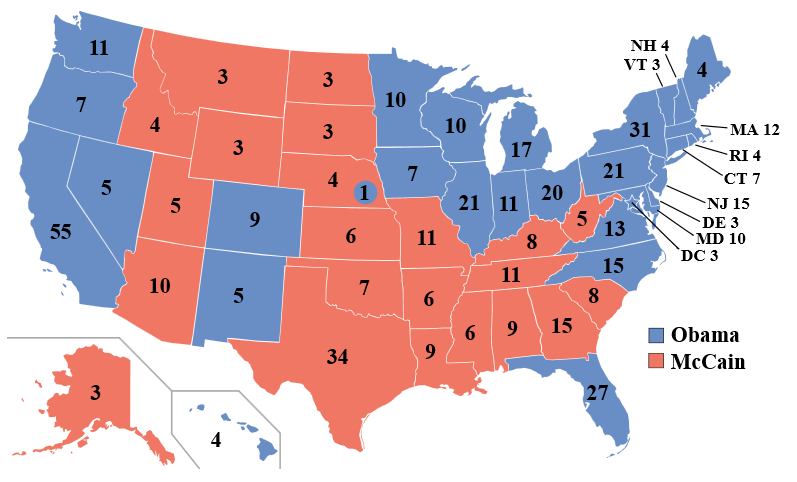

In 2004, it was the larger major political party, with 72 million voters (42.6% of 169 million registered) claiming affiliation. The current President of the United States, Barack Obama, is the 15th Democrat to hold the office, and since the 2006 midterm elections, the Democratic Party has held a majority in the United States Senate.

A 2011 USA Today review of state voter rolls indicates that registered Democrats declined in 25 of the 28 states that register voters by party. Democrats were still the largest political party with more than 42 million voters (compared with 30 million Republicans and 24 million independents ). However, in 2011, the number of Democrats shrank 800,000, and from 2008 they were down by 1.7 million, or 3.9%.

The other major contemporary political party in the United States is the Republican Party. It is often referred to as the GOP, which stands for “Grand Old Party,” or “Gallant Old Party”. Founded in 1854 by Northern anti-slavery expansion activists and modernizers, the Republican Party rose to prominence with the election of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican to campaign on the Northern principles of anti-slavery. The party presided over the American Civil War and Reconstruction but was harried by internal factions and scandals toward the end of the 19th century. Today, the Republican Party supports an American conservative platform, with foundations in economic liberalism, fiscal conservatism, and social conservatism.

Former President George W. Bush was the 19th Republican to hold that office. The party’s nominee for President of the United States in the 2012 presidential election is former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney. Since the 2010 midterm elections, the Republicans have held a majority in the United States House of Representatives.

USA Today’s review of state voter rolls indicates that registered Republicans declined in 21 of the 28 states that register voters by party, and that Republican registrations were down 350,000 in 2011. The number of independents rose in 18 states, increasing by 325,000 in 2011, and was up more than 400,000 from 2008, or 1.7%.

Provided by Boundless, published by Lumen Learning under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.